Introduction

Before, 1991, there was a functioning government in Somalia headed by the late Siad Barre. However, after the outbreak of the Somali civil war, in 1991, his government was dethroned by rebel forces comprising of different clans and supported by external forces, including some Ethiopians and Libyans (Doornbos 2002). Since the fall of the Barre regime, Somalia has never witnessed any meaningful form of government. Consequently, war, terrorism, famine and drought have characterized the East Africa nation, forcing many of its citizens to flee from the country. According to Barrett, Mude and Omiti (2007), about 2 million people live outside Somalia. Today, illiteracy, poor infrastructure and the breakdown of health care and education services characterize the state (Warah 2014). Based on these facts, some people have often painted the picture of Somalia as a nation that cannot effectively operate within a system set by a conventional state (Akpinarli 2010). Thus, for a long time, many researchers, academicians and political commentators have viewed Somalia as one of the world’s most iconic failed states.

In this paper, we argue that the lack of consensus-building and a bottom-up approach to state-building have largely contributed to Somalia’s failures. Key sections of this paper demonstrate that the most valuable lessons about state-building in Somalia could be learnt from Somaliland, which is an autonomous region within Somalia. Thus, they show that consensus-building and a bottom-up approach of designing a government are two aspects of state-building that have eluded international players in trying to create a stable government in Somalia. We use the success of Somaliland to support the above-mentioned assertions because although the region is not the first governance system to introduce democratization in the horn of Africa nation, it is the first government to merge electoral democracy with a nation-state government (The World Bank 2015). Our objectives in this paper are as outlined below:

- To find out what aspects of state-building have eluded international players in establishing peace and prosperity in Somalia.

- To investigate the social, political and cultural dynamics of Somaliland that have led to conflict and instability in Somalia.

- To establish why there has been no peace and stability in Somalia.

To meet these objectives, we will first explore the theoretical framework of the study. The paper will then provide an assessment of the country’s historical background to have a proper understanding of its political, economic, and social dynamics. The next section will be an analysis of the lessons we could learn about state-building in the horn of Africa nation. Finally, the paper will make the argument that consensus building and a bottom-up approach to state-building are needed to develop a strong and stable nation-state in Somalia.

Theoretical Framework

In the past century, state-building has become an important part of the international political system. Its proponents have lauded it as a peacebuilding concept characterized by security, political, and economic concerns (Leeson 2007). Broadly, security concerns are the most important when developing successful and prosperous nations (Jhazbhay 2003). The general argument across many academic and political fields is that it is difficult to realize other forms of prosperity (economic, social or otherwise) without first meeting security objectives (Ahmed & Green 1999). Therefore, international observers always argue that the first step to realizing political and economic gains in any society is to meet security goals (Giorgetti 2010). However, they have not realized widespread success in using state-building as an effective approach to create world peace. Evidence of failed interventions in Afghanistan, Iraq, the Balkans and even Somalia support this fact (Debiel et al. 2009). Existing literature on state-building has always presented the concept as a violent process characterized by two processes.

The first one is a theory supported by researchers such as Leeson (2007) and Silva (2014) who say that state building is a process spearheaded by external parties to realize political and economic prosperity in countries tinkering on the possibility of absolute failure. This school of thought is often premised on the principle that the actions of one state would dictate the outcome of another, especially through a formal international intervention, such as a United Nations (UN) peacekeeping intervention (Giorgetti 2010). The second process is defined by a different school of thought, proposed in 2007, by the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), which views state-building as an area of economic cooperation among different states (International Business Publications 2013).

Drawing heavily on political ideologies, which stem from research studies in political science, this school of thought presents donor actions as integral to the economic prosperity of different countries (Walls 2014). Broadly, this theory views state-building as an indigenous and national process characterized by developmental assistance. Nonetheless, state-building is an important part of the international political system. Although the concept has been around for a while, there is no shortfall of literature explaining how the international community has got it wrong in different parts of the world. Already, in this paper, we have highlighted how international interventions have worsened state-building efforts in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Somalia. This failure means that there are lessons we need to learn about the process, especially if we are to realize a wider goal of international peace and prosperity.

Historical Overview/Background

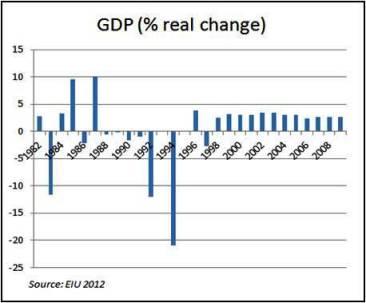

Somalia is located in East Africa (Horn of Africa). Officially known as the Federal Republic of Somalia, the country is bordered by Ethiopia, Kenya, the Gulf of Eden and the Indian Ocean. Population estimates show that the East African nation is home to more than 12 million people (Warah 2014). The International Business Publications (2013) says the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of the country is $6 billion and the per capita income is $600. The graph below shows the economic growth rate in the horn of Africa nation since the early 1980s.

According to the graph above, Somalia has only experienced moderate economic growth since the early 1990s, when Barre’s government collapsed. Estimates project that the average economic growth rate has been between 2%-3% (Briggs 2012). The moderate economic growth rate has been linked to economic activities in Somaliland and the growth of some economic sectors such as telecoms and the financial market (Briggs 2012).

Since 1992, there have been efforts by international partners to restore law and order in Somalia. Besides the American invasion of the 1990s, there have been attempts by several African nations to create political and social stability in the country (Shay 2011). Probably, the first major intervention was by Ethiopian forces, in 2006, which helped to create the Transitional Federal Authority (TFA) of Somalia, which was supposed to police liberated areas of Somalia from rag-tag militia groups (Shay 2011). Al-Shabaab (a terrorist group) was the enemy and although they were forced to flee from the capital, Mogadishu, they resorted to Guerrilla warfare (Walls 2014). A bigger contingent of forces from several African nations have intervened in Somalia and driven out this Islamist and Jihadi group in several other major towns of Southern Somalia. Although the control of Al-Shabaab has been significantly diminished, Somalia remains a fragile state.

Albeit the existence of different views surrounding the state of Somalia today, there is little doubt that the country has made considerable progress in the areas of political and social governance (in the past decade). Indeed, as Gordon and Gordon (2012) point out, most of Somalia’s problems today are contained. However, most of this progress is largely propped by the presence of foreign troops in the country. Their withdrawal could easily undo most of the progress that has happened. Nonetheless, the real prize of having a stable democracy and sustainable law and order still remains far from being realized. Since multiple international efforts to restore law and order in the country have not achieved their desired objectives, there are lessons we could learn from their failures. Furthermore, there are even more important lessons we could learn from the success of Somaliland.

Arguments/Analysis

Somaliland is perhaps the only form of the functional governance system in the state of Somalia that has existed since the fall of the Barre regime. The picture below shows its location on the Somali map.

Although Somaliland has not been recognized as a legitimate government by any foreign nation, we could borrow several lessons about state-building from the de-facto state. One important point to note is that Somalis are not inherently opposed to law and order, or civilization as we understand it in the literal sense of the word. In fact, Somalia has in the past demonstrated that it could build institutions that enjoy broad, if not general, nationalistic support. This is true for Somaliland, which stands as an example of a functional government within Somalia.

Contrary to the views of many international observers, Somaliland is not the first evidence of a successful state in the war-torn nation; throughout history, Somalia has had different trading towns that embraced a functional system of governance (Samoff 1980). For example, in the mid 14th century, there were several trading centres along the Somalia coast that shared some semblance of a functional political system (Samoff 1980). These towns set the country on the path of significant political and economic prosperity for more than 200 years (International Business Publications 2013). Evidence of this fact exists in the presence of 20 such trading centres along the Gulf of Eden coast. Counterterrorism in African failed states (2006) further says several empires sprouted in Somalia because of the prosperity of trading centres along its coast.

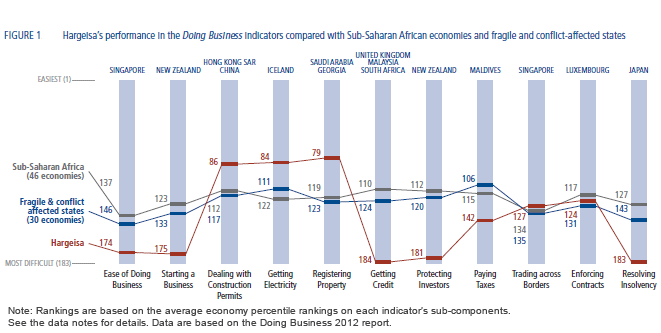

Menkhaus (2006) contends that the Somaliland government has attracted widespread praise in its ability to build capacity and promote economic growth since the late 1990s. The graph below shows the country’s performance in terms of ease of doing business, relative to other Sub-Saharan countries and nations that have experienced conflict.

Although the future could pose substantial challenges to the progress that has already been made in Somaliland, a close look at the region’s political, economic, and social systems provide us with valuable lessons about how to build a successful nation-state in Somalia. One of the lessons is on consensus building as a form of government.

Consensus-based Political Participation

Somaliland often relies on a consensus-based political system that has given legitimacy to the region’s rulers (Republic of Somaliland 2011). Although it is not perfect, like other democratic systems around the world, some observers believe that its importance is the same as other democratically elected governments around the world (Pham 2012; Walls 2009). To support this assertion, Walls (2014) says that, “This system is inevitably imperfect, but it has played a key role in securing broad, though qualified, acceptance of state institutions” (p. 1).

According to Leonard and Samantar (2011), most of the successive governments in Somaliland have built legitimacy through negotiated democracy where power players attend conferences and a consensus is made regarding who would be the region’s next president. Most of these conferences are clan-based and they have been held since the fall of the Barre regime (Pham 2012; Walls 2009). Although this type of democracy is not ideal (compared to the western form of democracy), there are many clans in the region, none of which could garner enough legitimacy to rule without seeking the support of others (Lennartz 2007; Pham 2012). In other words, there needs to be sufficient support from the population before a government in Hargeysa (Somaliland’s de facto capital) assumes legitimacy as the ruling authority (Republic of Somaliland Constitution 2006; Lennartz 2007).

Leveraging its potential in fostering a democratic society in the country, Walls (2014) says, “That system is both highly inclusive – for men – and slow and cumbersome. It is not dissimilar to the type of discursive democracy practised in the city-states of ancient Athens” (p. 5). In this regard, researchers say that the system cannot be described as non-functional unless we use a narrow prism to define democracy as a system that is only ideal when it eliminates all exclusionary cohorts (Garcia & Sunil 2008).

Based on this fact, we should understand that the success of Somaliland does not focus on democratization at all; instead, it is one that allows men to cede some of their decision-making rights for the greater good of speedy decision-making and the inclusion of other parties, such as smaller clans and women, in the political and governance structure of the country (Crawford & Hartmann 2008). Therefore, if Somalia has to adopt the concept of state-building and nurture one that is successful and prosperous enough to participate in the league of nations, or invite multinational companies to do business in the country, it needs to have a political system that allows for representative politics and one that recognizes the holistic participation of all types of governments (Biggar 2002; Ahere 2013).

Compressively, the evidence gathered in this section of the study shows us that there need to be deliberate consensus-building efforts when developing a strong, legitimate and sustainable nation-state in Somalia. This effort would typically involve considering the views of all relevant parties, clans, and kinships when developing a national government. Current efforts at state-building are exclusionary. As opposed to adopting a system where the majority rules, there needs to be a deliberate effort to make sure that the views of the monitory are also heard. In other words, adopting a “winner-take-all” strategy, which is synonymous with most western democracies, would fail to create the desired outcome in Somalia. Already, the people are wary about this type of system because it has been repressive to them. Overcoming such trauma and mistrust may take some time. In the meantime, adopting a system that recognizes consensus-building would be a welcome approach to state-building. The success of Somaliland, which has implemented this system, justifies this view.

Top-down State Building does not Work

A top-down state-building approach has been the main dogma characterizing western-styled political governance systems (Garcia & Sunil 2008). Many countries have adopted this model, which is a direct offshoot of colonial governance systems. The same is true for Somalia. While many countries in Africa have adopted this leadership and political governance system with relative success, it has not gained traction in Somalia because of the prevalence of kinship identities. To affirm this fact, Upsall (2014) says, “In post-conflict Somalia, the top-down approach to state-building has been ineffective and a lack of government structure at the time of independence created an environment in which clan-based fracturing of the government was inevitable” (p. 1).

Kibble (2001), Garcia and Sunil (2008) also support the fact that a top-down state-building model cannot work in Somalia because more than 16 attempts by international partners to restore peace and stability in Somalia have failed. For example, many transitional governments (backed by the international community) have failed to live up to their name because they have failed to get the respect or authority, that is worthy of its name. Researchers who have investigated this matter deeply say that the failure of Somalia to adopt a western-styled top-down model of governance has fuelled ideas that the country is a failed state (Ferguson 2002; International Business Publications 2013). However, this notion, or idea, is only true if we evaluate Somalia’s governance and political system from a western-style model. Byrne (2013) supports this view by saying that, “The failed state discourse occludes the reality of the situation and is harmful to attempt to encourage development from within the country” (p. 213).

The failure of the top-down governance model to create a stable government in Somalia partly stems from deeply rooted belief systems and notions among the Somalis that the model is only meant to enrich those people at the top and oppress those who are not within close proximity to power (Ferguson 2002). The last known legitimate government of Somalia is largely responsible for brewing such beliefs and ideas among the Somalis because Barre used the state’s resources to oppress those who did not support his regime (Walls 2009). In fact, historical excerpts report that the regime valued loyalty more than merit and experience (Posner 1980). Consequently, family members and those who were deemed to be loyal to the ruling regime were appointed to powerful positions in the country. The president also used parallel clan-based militias to oppress those who were disloyal to the regime (Ferguson 2002). Although there were law and order during the Barre regime, armed forces and the police force enforced it, not because they were professional, but because they were loyal to the ruling regime (Kaplan 2008).

Part of the reason for the distrust in government also stems from the misuse of foreign aid and state resources to finance the government’s oppressive practices during the Barre regime (Capobianco & Naidu 2008). During its time, foreign aid accounted for more than 57% of Somalia’s Gross National Product (GNP). Indeed, from 1972 to 1989, Somalia received more than $2.8 billion in foreign aid, making it the single largest recipient of foreign aid in Africa at the time (Capobianco & Naidu 2011). In fact, reports show that, in the 1980s, foreign donors financed most of the country’s development budget (International Business Publications 2013).

Contrary to the expectations of the donors, the foreign aid support provided little benefit to the Somalis because it was channelled to providing kickbacks to ruling elites (Ferguson 2002). Furthermore, it helped to fuel a wave of corruption in the country that led to the failure of most of the country’s institutions of governance. Therefore, many political analysts believe that foreign aid helped to prop up Barre’s oppressive regime (Pham 2012; Walls 2009). These outcomes made it difficult for people to trust a centralized system of governance. More importantly, it made them sceptical about the possibility of legitimizing a centralized governance system that was not inclusive. Hence, it was difficult to support a top-down governance model.

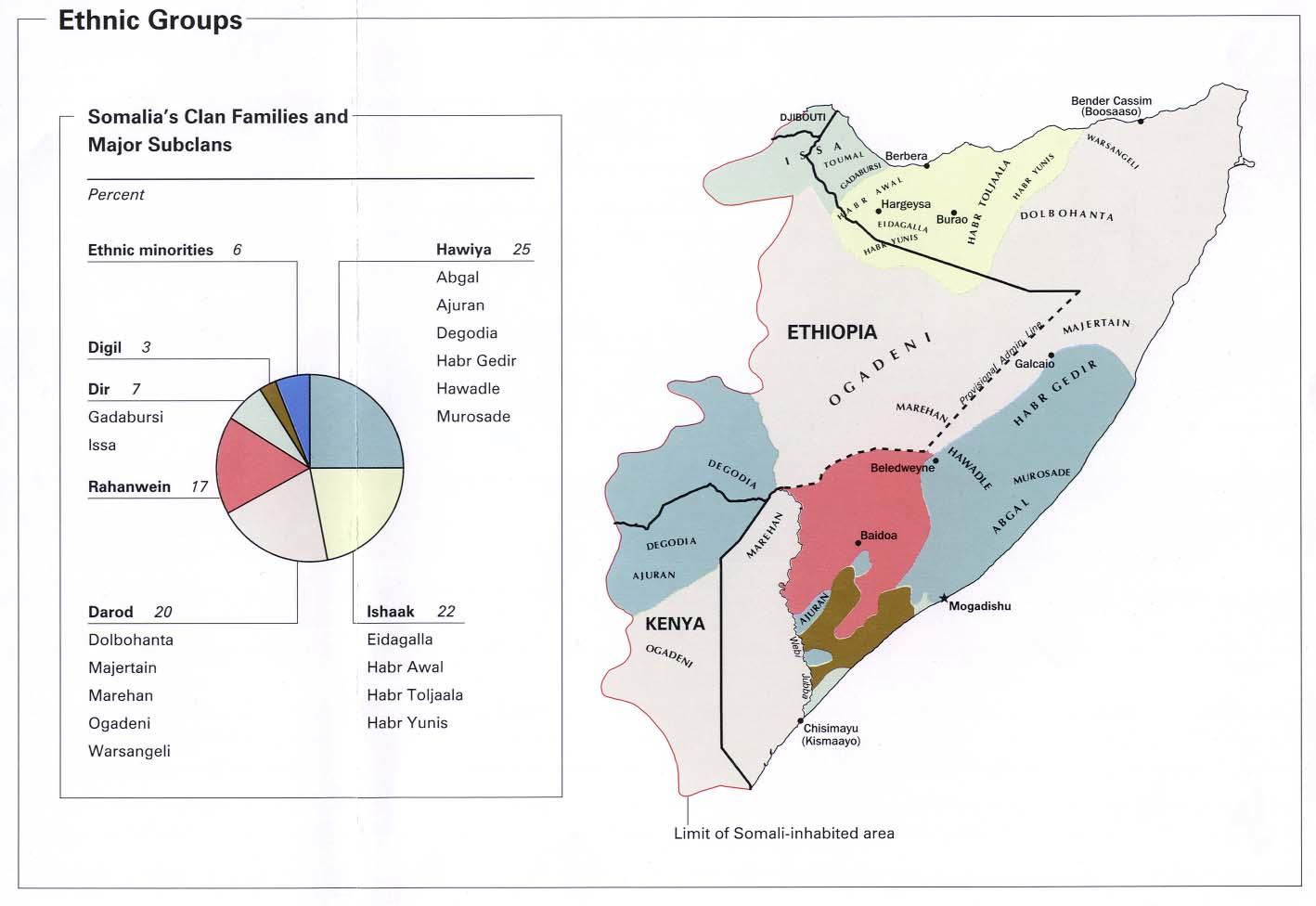

The success story that is neighbouring Somaliland has largely been ignored by many international actors because it does not fit within the western-styled model of governance. Nonetheless, it is the only existing and successful model of government that Somalis have accepted. The governance system in the region is largely characterized by highly placed political orders and norms that are a fine blend between traditional and modern norms and practices. Relative to this assertion, Jhazbhay (2003) says, “Somaliland has used traditional practices to create a sustainable modern government by blending modernity and tradition into a functioning state” (p. 51). The success of Somaliland is largely premised on its ability to recognize the legitimacy of clan elders and the role of clans and kinship in the country’s political and governance model (Pham 2012; Walls 2009). The diagram below shows the ethnic groups in Somalia.

The top-down model of governance fails to recognize these social and cultural dynamics of Somalia (Renders 2012). The bottom-up model of governance (recognized in Somaliland) is also a success story because it derives its legitimacy from the local ownership of civil institutions that promote a local, stable, political, and security environment for all people to thrive (Republic of Somaliland Constitution 2006; Republic of Somaliland 2011). In this regard, Kibble (2001) says, “Compared to international attempts at imposing western-style government in Somalia, the Somaliland nation-building process was more bottom-up and does function as a state” (p. 18). Thus, the methods used in Somaliland in state formation may provide the best model for designing a sustainable political and governance system in Somalia that would pass the test of time. Clearly, state-building efforts in Somalia must focus on a bottom-up organic growth model, as opposed to the imposition of institutions and governance structures (stemming from a top-down governance model) supported by enthusiastic Somali nationals and the international community (North 1990).

Conclusion

This paper has already shown that there has been significant progress made in Somalia to prop up its political and social institutions. This progress, albeit positive, has diverted attention from the lessons we could learn about state-building from Somaliland, which shares the same political and social dynamics as Southern Somalia. Indeed, as we have seen from the recent works of political commentators and experts who have explored this issue, the mundane lessons we have learned from Somaliland, about the bottom-up and consensus-based political participation models, have quickly been relegated to the margins. International partners and well-wishers based in some of the world’s major capitals, such as London, Nairobi, and Washington have been more focused on the idea of building a successful nation-state, based on the realpolitik of the region, disregarding the historical and cultural context of state-building in Somalia. This has been the main problem in the region.

There needs to be a significant paradigm shift in the way international partners and organizations develop solutions for the country because a fixation on implementing a top-down governance model, which has worked in western democracies, on a country that greatly values clan politics and kinship will not work. Pouring international aid and finances into this “uninformed model” of governance may yield some significant success in the short-term, but would fail to hold in the long-term either because it does not recognize the role of consensus building and adopting a bottom-up approach in building the nation’s political and governance systems. Broadly, the main lessons that we can learn about state-building in Somalia are that a one-size-fit-all approach does not work with all nations. Therefore, future efforts at promoting political, security, and economic stability should borrow from some of the lessons we have learned about consensus building and the implementation of a bottom-up leadership model in Somalia.

Reference List

Ahere, J 2013, The paradox that is diplomatic recognition: unpacking the Somaliland situation, Anchor Academic Publishing, London.

Ahmed, I & Green, R1999, ‘The heritage of war and state collapse in Somalia and Somaliland: local-level effects, external interventions and reconstruction’, Third World Quarterly, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 113-127.

Akpinarli, N 2010, The fragility of the ‘failed state’ paradigm: a different international law perception of the absence of effective government, BRILL, London.

Albin-Lackey, C & Human Rights Watch 2009, Hostages to peace: threats to human rights and democracy in Somaliland, Human Rights Watch, London.

Barrett, C, Mude, A & Omiti, J 2007, Decentralization and the social economics of development: lessons from Kenya, CABI Publishing, Wallingford.

Biggar, N 2002, ‘Peace and justice: a limited reconciliation’, Ethical Theory and Moral Practice, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 167-179.

Briggs, P 2012, Somaliland: with Addis Ababa & Eastern Ethiopia, Bradt Travel Guides, London.

Byrne, M 2013, ‘The failed state and failed state-building: how can a move away from the failed state discourse inform development in Somalia’, Birkbeck Law Review, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 111-134.

Capobianco, E & Naidu, V 2008, A review of health sector aid financing to Somalia, World Bank Publications, London.

Capobianco, E & Naidu, V 2011, A decade of aid to the health sector in Somalia, 2000-2009, World Bank Publications, London.

Counterterrorism in African failed states: Challenges and potential solutions 2006, DIANE Publishing, London.

Crawford, G & Hartmann, C 2008, Decentralization in Africa: a pathway out of poverty and conflict, Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam.

Debiel, T, Glassner, R, Schetter, C & Terlinden, U 2009, ‘Local state-building in Afghanistan and Somaliland’, Peace Review: A Journal of Social Science, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 38-44.

Doornbos, M 2002, ‘Somalia: alternative scenarios for political reconstruction’, African Affairs, vol. 101, no. 402, pp. 93-107.

Ferguson, N 2002, Empire: The rise and demise of the British world order and the lessons for global power, Basic Books, New York.

Garcia, M & Sunil, A 2008, Achieving better service delivery through decentralization in Ethiopia, World Bank Publications, Herndon.

Giorgetti, C 2010, A principled approach to state failure: international community actions in emergency situations, BRILL, New York.

Gordon, A & Gordon, D 2012, Understanding contemporary Africa, Rienner Publishers, London.

International Business Publications 2013, Somalia business law handbook: strategic information and laws, Int’l Business Publications, New York.

Jhazbhay, I 2003, ‘Somaliland: Africa’s best kept secret, a challenge to the international community’, African Security Review, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 77-82.

Kaplan, S 2008, ‘The remarkable story of Somaliland’, Journal of Democracy, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 143-157.

Kibble, S 2001, ‘Somaliland: surviving without recognition; Somalia: recognized but failing’, International Relations, vol. 15, no. 5, pp. 5-25.

Lennartz, N 2007, ‘The law of the Somalis: a stable foundation for economic development in the Horn of Africa’,Journal of Libertarian Studies, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 129-133.

Leeson, P 2007, Better off stateless: Somalia before and after government collapse, Web.

Leonard, D & Samantar, M 2011, ‘What does the Somali experience teach us about the social contract and the state’, Development and Change, vol. 42, no. 2, pp. 559-584.

Menkhaus, K 2006, ‘Governance without government in Somalia: spoilers, state building, and the politics of coping’, International Security, vol. 31, no. 3, pp. 74-106.

Millman, B 2013, British Somaliland: An administrative history, 1920-1960, Routledge, London.

North, D 1990, Institutions, instructional change and economic performance, Cambridge University Press, New York.

Pham, J 2012, ‘The Somaliland exception: lessons on post-conflict state building from the part of the former Somalia that works’, Marine Corps University Journal, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 1-33.

Posner, R 1980, ‘A theory of primitive society, with special reference to law’, Journal of Law and Economics, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 1-53.

Renders, M 2012, Consider Somaliland: state-building with traditional leaders and institutions, BRILL, London.

Republic of Somaliland 2011, Somaliland national vision 2030. Web.

Republic of Somaliland Constitution 2006, Somaliland government. Web.

Samoff, J 1980, ‘Underdevelopment and its grassroots in Africa’, Canadian Journal of African Studies, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 5-36.

Shay, S 2011, Somalia between jihad and restoration, Transaction Publishers, London.

Silva, M 2014, State legitimacy and failure in international law, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, New York.

The World Bank 2015, Somaliland’s private sector at a crossroads: political economy and policy choices for prosperity and job creation, World Bank Publications, London.

Upsall, K 2014, ‘State building in Somalia in the Image of Somaliland: a bottom-up approach’, Inquiries Journal, vol. 6, no. 3, p. 1-4.

Walls, M 2009, ‘The emergence of a Somali state: building peace from civil war in Somaliland’, African Affairs, vol. 108, no. 432, pp. 371-389.

Walls, M 2014, State building in the Somali Horn: compromise, competition, and representation, Africa Research Institute, London.

Warah, R 2014, War crimes: how warlords, politicians, foreign governments and aid agencies conspired to create a failed state in Somalia, Author House, London.