Significance of the Issue

The present brief is devoted to the famine that was declared in South Sudan on February 20 of this year (Ombuor 2017, para 1). It is an unprecedented event for South Sudan with roughly 42% of the country’s population (4.9 million people) being “severely food insecure” (Integrated Food Security Phase Classification [IPC] 2017, p. 1). The term presupposes the presence of phases 3, 4, or 5 of acute food insecurity, which corresponds to the cases of crisis (“high or above usual acute malnutrition”), emergency (“very high acute malnutrition and excess mortality”), and catastrophe (starvation, high mortality) (Integrated Food Security Phase Classification n.d., para. 10-12).

The region of Greater Unity experiences the most significant strain with some of its counties experiencing phase 5 classification in January 2017 (IPC 2017, p. 2). However, the issue of malnutrition has become acute for the entire nation (Famine Early Warning Systems Network [FEWS] 2017). The situation is expected to deteriorate without an appropriate response (IPC 2017). The latter should not be limited to humanitarian aid: the primary causes of the issue, which include the ongoing conflict in the region, need to be investigated and addressed before more than a half of the population of the country is affected by the famine (Clooney & Prendergast 2017; FEWS 2017).

Analysis

The current crisis, while unprecedented, was predicted by the WHO (2016, p. 1) that reported growing food insecurity in the region, which coincided with unfavourably dry weather conditions. Indeed, the recent drought, which affected certain areas of Africa, contributed to the problem, resulting in agricultural difficulties and increases in food prices (IPC 2017, p. 4; World Health Organization [WHO] 2016). However, the famine proves to be a result of a more complex combination of issues (BBC News Team 2017).

One of the primary causes of the famine are the armed conflicts of the ongoing civil war, which started in 2013 (Ombuor 2017; Quinn 2017). It is apparent that war can have multiple negative consequences, and one of them is disruptions in the economy caused by destruction, looting, and violence (Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights [OHCHR] 2016; WFP 2017).

In particular, IPC (2017) shows that armed conflicts in South Sudan have a tendency to disrupt agricultural activities (p. 5). It is noteworthy that the tactics of the warring parties include attacking civilians (in particular, raiding communities and depriving them of cattle, food, and money), which has greatly contributed to the famine (Clooney & Prendergast 2017, para. 3). Moreover, there are reports of humanitarian aid, including food trucks, being hijacked or blocked by both sides of the conflict (Gettleman 2017, para. 19). The aid could have prevented the drought-related food insecurity or reduce its severity, but the strategy of the warring parties prevented this outcome (Clooney & Prendergast 2017).

In the end, the growing food insecurities and conflicts created a combination which set in motion various contributing factors, including a tremendous loss of lives, health crisis, hyperinflation, changes in the Terms of Trade, the lack of access to healthcare, and others (BBC News Team 2017; FEWS 2017; IPC 2017; OHCHR 2017; WFP 2017).

It is noteworthy that the previous famine, which Bahr El Ghazal region experienced in 1998, was caused by similar issues, including the fight for the independence of South Sudan and a drought (BBC News Team 2017, para. 19; Ombuor 2017, para. 15). Indeed, famine was used by the government as a part of its strategy against the rebels (Clooney & Prendergast 2017, p. 5). Coupled with unfavourable weather conditions, the strategy caused immense food insecurity, which was the most devastating one experienced by Sudan before the events of 2017. The recent famine, however, proves to be more destructive (Ombuor 2017, para. 15).

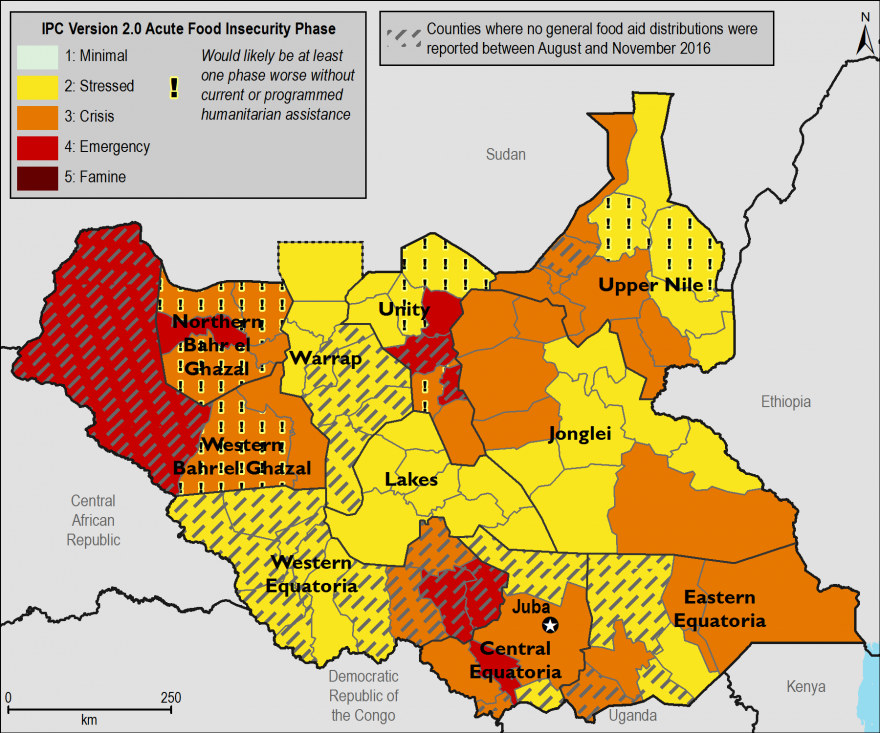

Famine is a major issue, and officially declared famines are particularly dangerous (BBC News Team 2017, para. 12; Clooney & Prendergast 2017). As of January 2017, the following classifications of the situations in South Sudan regions were made by IPC (2017, p. 13).

Over 50% of the population of Greater Unity and Northern Bahr el Ghazal were classified as experiencing phase 3, 4 or 5 of acute food insecurity. In Jonglei, more than 40% of the population experienced phase 3 or 4, and more than 30% of the population of Central and Eastern Equatoria were shown to suffer from the same levels of acute malnutrition. The remaining regions had less than one-third of their population experiencing phases 3, 4, or 5, but only the population of Western Equatoria showed no signs of phase 4, remaining classified as suffering from the three first phases of acute malnutrition. An illustration of the classifications can be found in the Image below. Thus, it is apparent that the situation is dire across the country, and action needs to be taken to avoid deterioration and ensure improvements.

Conclusion

The officially declared famine in South Sudan has already affected over 40% of the country’s population, which means that hundreds of thousands of people are in direct danger of starving to death while the quality of lives of several millions of people is incredibly and increasingly low (Clooney & Prendergast 2017). IFSPC (2017, p. 1) expects the situation to proceed to deteriorate between February and July, eventually affecting about 5.5 million people, but the organisation does not attempt to make predictions for more extended periods of time.

The analysis demonstrates that multiple issues have contributed to the development of food insecurities and famine. However, certain officials of the World Food Program are reported to call the famine “man-made” (WFP 2017, para. 10; Ombuor 2017, para 2). While seemingly one-sided, this comment also implies that humans have a greater opportunity to control the issue by investigating and addressing human-made problems that have led to food insecurities.

Given the fact that the famine is the result of a complex of issues, a complex of interventions is required to improve the situation. Humanitarian aid (including direct provision of food, water, and medications as well as help in restoring agriculture) has been shown to have a positive impact, and it is expected to be beneficial in the future as well (Quinn 2017; WFP 2017). However, WFP (2017) states that humanitarian aid is only a part of the solution, predominantly because it does not affect the human-related reasons of the famine. The latter are likely to be affected through governmental efforts.

In particular, FEWS (2017, para. 1) insists that a noticeable improvement of the situation is only possible if the conflict is ended, and calls for attempts to reduce violence while directing the efforts of the government towards emergency management and saving lives. Similarly, Clooney and Prendergast (2017) point out that war crimes, including looting, should not be overlooked; they need to be punished to prevent them from occurring. They also suggest that the war crimes must have resulted in wealth for some of the leaders of the conflicting parties, and they recommend anti-money laundering measures which can help to make such a form of property acquisition less attractive. Thus, it can be concluded that the resolution of food insecurities in South Sudan is only possible with a direct, active, and meaningful cooperation of the government of the country.

Reference List

BBC News Team 2017, ‘South Sudan declares famine in Unity State’, BBC News. Web.

Clooney, G & Prendergast, J 2017, ‘Famine declared in parts of South Sudan’, The Washington Post. Web.

Famine Early Warning Systems Network 2017, Alert Famine (IPC Phase 5) possible in South Sudan during 2017. Web.

Gettleman, J 2017, ‘Drought and War Heighten Threat of Not Just 1 Famine, but 4’, The New York Times. Web.

Integrated Food Security Phase Classification 2017, The Republic of South Sudan. Web.

Integrated Food Security Phase Classification n.d., IPC 2.0: A common starting point for decision-making. Web.

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights 2016, UN report contains “searing” account of killings, rapes and destruction. Web.

Ombuor, R 2017, ‘Famine declared in South Sudan, with 100,000 people facing starvation’, The Washington Post. Web.

Quinn, B 2017, ‘Famine declared in South Sudan’, The Guardian. Web.

World Food Programme 2017, Famine hits parts of South Sudan. Web.

World Health Organization 2016, El Niño and health South Sudan overview. Web.