Introduction

As a part of the proposal for the present research, a preliminary study was conducted, imitating the design and the methodology outlined in this paper. The only factor changed was the duration of the study and the number of participants. The results of this study should be used to provide a clear insight into the expected results of the complete study in the future as well as pointing out the potential limitations and deficiencies that can be avoided. The preliminary study was conducted over 6 weeks in a high school.

The study included 6 Spanish native speakers who participated voluntarily enrolled in Spanish classes. The study was a mixed approach in which the quantitative part was a survey that the students took before the enrollment. Other quantitative aspects of the preliminary study include the assessment of performance after the completion of the study.

The qualitative part, on the other hand, was comprised of interviews that were taken after the period of class enrollment was finished. Accordingly, several interviews were taken with the two teachers that participated in the preliminary study, to assess their perceptions and provide an assessment of the student’s academic performance.

It should be stated that limited resources, as well as the preliminary nature of the study, were an influential factor in choosing the number of participants. The latter in turn was reflected in the facilitation of data collection and analysis. The Spanish classes were language-only classes, where the main emphasis was put on Spanish grammar and vocabulary, implemented through language learning aspects such as listening, reading, writing, and speaking.

Participant Selection

The main criterion for the selection of the participants was their Hispanic background, for which Spanish was the first language, as well as the variability of their parents’ academic background, being a part of the research questions. The participants should be currently enrolled in Spanish foreign language classes, in which the population is mixed with non-native Spanish speakers. It should be noted that an important aspect was in choosing students who do not come from a bilingual family, where the distinction of Spanish as the mother tongue would be hard to make. In that regard, contact with local school representatives was made to obtain permission to conduct the study and receive help in participants’ selection.

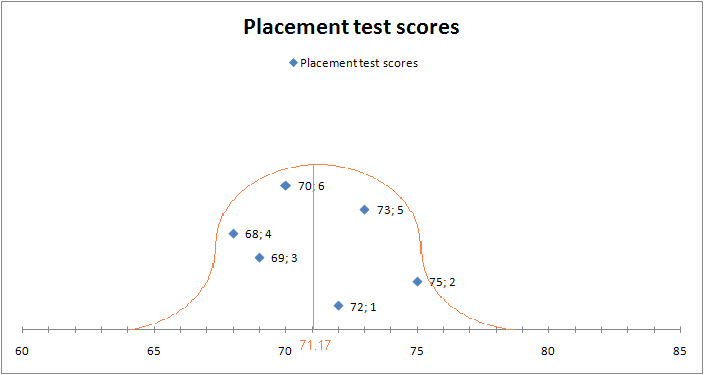

Other important factors included age and current mastery of the native language. For academic performance purposes, it was decided that the age difference between the oldest and the youngest participant should not exceed the limit of three years. Accordingly, a placement test in the Spanish language would be conducted to select participants with a similar level of performance (Teschner, 1987). In that regard, the existent pool of the 130 students was reduced to six participants, with the oldest being 16, while the youngest being 14 years old. The placement test was conducted on a 100-scale mark, with the average score of the participants being 71% and a standard deviation of 2.5.

Data Collection

The data for the preliminary research was collected through different sources, considering the mixed nature of the research. These sources included the results of the placement tests, the surveys, and the interview conducted with the students and the teachers. The qualitative data was collected through informal semi-structured interviews, held separately with teachers and students. The interviews were collected through a period of 5 days after the completion of the teaching period.

The surveys, on the other hand, were collected before the initiation of the study period. In that regard, the surveys replaced interviews at that period so that general assessment was made as well as to determine the backgrounds of the students as variables in the study, while the interviews consisted of perception relating to both periods, i.e. before and after the study, and were tape-recorded for further analysis. The surveys were collected through emails, where the administration of the school distributed the surveys to the participants and emailed them after the students completed them.

Data Analysis

Different methods of data collection were implemented for the preliminary study, including diagrams and charts for the quantitative parts, and transcription of the interviews for the qualitative parts. The themes of the interviews were predetermined before taking the interviews, where the transcripts were arranged into the themes and patterns, “looking for recurring regularities” (Merriam, 2009, p. 177), which were subsequently reported.

Results

This section reports the results of the preliminary study conducted as a part of the action research proposal described in this paper. In that regard, the results expected from the main study proposed are to be based on the results of the preliminary study. Even though the preliminary study was limited in scope, it can be stated that the main methodological aspects were imitated, in terms of participants selection, data collection, analysis, and reporting.

Accordingly, the findings of the action research proposal are expected to resemble the findings of the preliminary study. The first part of this section is devoted to reporting the quantitative data of the study, while the second part indicates the results of the qualitative sections of the study, revealing the perceptions of the students and the teachers taking the class. Part summarizes the results of the academic performance test after the study, providing discussions on the major findings and the way these data can be connected to the current theory and practice in education.

The main finding of the preliminary study indicated a distinct dissatisfaction with the Spanish class experience, where despite the small sample it can be stated that the majority find studying the Spanish language either boring or slightly above such indicator. At the same time, a distinction can be seen between the language spoken at home and school, with the mix of Spanish and English seen as an average while an inclination toward a specific language distinguishes the school (English) and home (Spanish). While the majority of the participants indicated that there is progress studying Spanish, this majority was seen in most of the students studying Spanish for less than a year. In that regard, it is difficult to make an assessment considering that for the majority of students the class experience was boring.

English, on the other hand, was studied for longer periods for most of the students, while an assessment of the English proficiency level should have helped to establish a relationship between proficiencies in both languages. With most students ranking their performance as good, the placement test indicated that the level of Spanish is average.

Another finding of the pre-study period survey indicated a direct correlation between the backgrounds of the parents and the results of the placement test. Although the size of the sample can be considered as a limitation in this case, specifically in terms of validity, the establishment of a causal effect was not within the scope of the preliminary study at this stage.

Background

The main emphasis in the preliminary study can be seen through the results of the qualitative part of the preliminary study. These results can serve as an indication of the expected results of the proposed action research. All of the six students stated that mainly relied on English or English mixed in Spanish while they are in school. The shift toward Spanish at home or mixed English and Spanish was never an indication of the mastery of their native language. Accordingly, the majority speaking Spanish and English was explained as a prevalence of English language in everyday life, where even speaking with parents in Spanish was rare, switching to mixed language instead.

As stated by one of the participants, “I remember talking in Spanish and English all my life, without even recognizing that I switched languages. In our family it was like that: If my father would ask me something in Spanish I would respond in the same language. Gradually, common words are replaced with their English analogs, because we use them more frequently and in the heart of a speech, it is easier for me to say “Hey, I’m going out”, rather than “Voy a salir”. I’m used to many words being Spanish though, and sometimes I refer to them in Spanish, when speaking with non-Spanish friends.”

Another participant limits his Spanish language experience to the conversation with parents, “I talk English all the time. I can say that 3-4 years ago, I was talking in English and Spanish. Now, I talk in English all the time. I talk in Spanish with my parents only. Mostly, with my mom as she is the one always at home. Other than that, I can’t say that there are cases when I would use my Spanish.”

It should be noted that for three of four participants, code-switching was a normal practice that they were not aware of. The latter is specifically evident though students who indicated that they speak mostly in English, while they were code-switching frequently during the interview. Additionally, those students who code-switched the most were likely to make grammatical errors during the interview as well.

Such errors were not significant, and they were not an indication of English language proficiency as compared to Spanish, rather than the existence of weaknesses in oral Spanish. An example of such mistakes include saying “No me realicé” instead of “No me di cuenta”, switching the places of nouns and adjectives, e.g. fácil idioma, and other examples.

“Traditional” Spanish Class

The Spanish class experience outlined several distinct themes, which included the level of the materials taught. Although the participants ranked the materials differently, common themes could be outlined. One of such themes is the different focus, as stated by one of the participants:

“I can say that I’m better in Spanish than any other non-Spanish student, but I sometimes get lower marks. They [non-Spanish students] might be better at grammar, while I took my language for granted. While we study I know all the answers, but while we write or read I make mistakes.”

Another student outlined different characteristics of Spanish speaking students and non-Spanish speaking students, which make the Spanish class “boring,” “I know that my Spanish is not perfect. I don’t speak like Spanish TV hosts or reporters. Generally, I’m better than non-Spanish speaking students, but it’s not what matters. It’s just that we have different strengths and weaknesses. I’m good at oral and spoken Spanish. If I hear a Spanish text I understand it. They are better in grammar and spelling. But, that does not make us or them better, we just have different needs”

The pronunciation is also a factor in the traditional class. Participants indicated that the pronunciation of their non-Spanish speaking peers is poorer than theirs. When asked about their perceived reasons for deficiencies in written tests, they almost unanimously state their lack of focus on grammar.

Spanish for Native Speakers

The SNS class experience showed that the student wanted to improve their native language, with the experience, in general, being more enjoyable. In that regard, the latter is a clear indication that there is a personal dimension for the participant in studying Spanish, rather than being purely academic. Dividing the SNS experience into such dimensions, the academic dimension consisted of the theme of learning more.

Two of the participants indicated their need to learn more Spanish vocabulary, where one student stated, “I watch Spanish shows on TV, or listen to Spanish music, and I can understand everything said. When my parents talk with other relatives I can understand everything they say as well. Sometimes, some of the words I understand only their general meaning in the context of what is said. If someone asked me in a separate case, what this particular word means, I would not know.”

Expressing deeper ideas in Spanish was another common theme, as stated by another participant, “In SNS class we learned how to structure longer sentences, which are more complex than what we were doing before. I can understand Spanish, but I can say that it is difficult to enter into longer discussion solely in Spanish.”

A comparison between Spanish as a foreign language and the SNS was constantly arising during the interviews, where the students were indicating that the SNS was a different experience. In that sense, reading and writing in Spanish were one of those themes. The students stated that the course was more responsive to their needs, considering that the majority of the students had grammar problems. Another factor indicated by the participants can be referred to as the cultural theme.

As stated by one of the students, “I liked the class because we had a lot in common. Everything was in Spanish; we were talking together fluently, with good communication with everyone. The best thing about it is that it didn’t feel like being in class. It was like having fun.”

The final indication can be seen through the improvements in test scores, as compared to the placement test before the study. All participants showed a significant improvement in test scores. The increase in scores showed around 12 percent on average, with a single exception showing an impressive 19 percent improvement. Such might be indicative of the expected results of the proposed action research.

Discussion

Theory

Several results from the preliminary study can be connected to the native language theories, in a sense specific to the awareness of knowing; “Native speakers are not necessarily aware of their knowledge in a formal sense” (COOK, 1999). The perception of the traditional Spanish course specifically in terms of the difficulties that might be faced corresponds to those outlined generally in literature.

The indication of different focus can be paralleled with different objectives, in a sense that “Spanish programs in the United States have as their goal the preparation of students with the knowledge of the spoken and written language based on literary models” (Merino, Trueba, & Samaniego, 1993, p. 88). The latter can be expanded to include the pace at which sub-objectives are reached, often taking into consideration of the non-native speakers’ abilities. Such courses do not consider the patterns and the structures of the oral language, which form an important part of the knowledge of native speakers.

Accordingly, such fact results in Hispanic students, “who many times drop out of courses because they consider them to be intolerable” (Merino, et al., 1993, p. 88). The rationale for having SNS classes, in that regard, supports the notion of the language deficiencies in native speaking students, i.e. committing errors since childhood and limited time spent in classrooms (Teschner, 1987, p. 268).

Practice

In practical aspects, it can be stated that the objectives of the SNS course are wider than those of traditional Spanish classes. In addition to maintaining the Spanish language, such courses usually strive to achieve such goals as the “acquisition of a prestige variety of Spanish… expanding the bilingual range (i.e. the expansion of a variety of competencies in Spanish, including grammatical, textual, and pragmatic competence), [and] transferring literacy skills from one language to another” (Carreira, 2007, p. 151).

With a focus paid to a variety of SNS programs, since late 1970, the main implication of the proposed study can be seen through the feasibility of putting native speakers in SNS courses, distinguishing the scope of traditional and native language learning. Accordingly, the findings of the preliminary study confirm the focus of SNS instructions, outlined in Valdes (1997), cited in (PEYTON, LEWELLING, & WINKE, 2001), i.e. grammatical correctness.

The scope can be extended to that “instructors should build on what students already know rather than trying to replace it” (PEYTON, et al., 2001, p. 2). Accordingly, such distinction can be reflected on non-native speakers, whose objectives, goals, and in turn, educational processes differ from those of native speakers. It can be predicted that their academic achievements should be influenced by separating native speakers into distinct groups, although such an assumption might require further investigation in empirical studies.

Conclusion

The present proposal suggests that placing native Spanish speakers in a classroom of their own to study Spanish can have a positive effect on their performance in their native language. The results of a preliminary study confirm such suggestions, which despite being conducted with a small sample, implies that the results of the actual study will resemble similarly. The limitations of the proposed study can be seen in terms of generalization, while the diversity of the sample characteristics, their initial academic performance, and the diverse educational background of their parents might have a confounding effect on the study’s results. In that regard, it will be suggested that the proposed study consider all the variables involved.

The main implication of the proposed study is that there is a need for SNS programs, specifically considering areas with a large Spanish population. It was found that performance in Spanish is certainly affected when students are placed in Spanish as a foreign language class. The cultural implication is also an important factor, were considering the implementation of an SNS program in a certain educational institution is a creation of a culturally supportive environment for Spanish students. Another aspect that should be considered in the preparation of the SNS teachers, considering the different needs of native speakers. The assessment methods, accordingly, should be developed to match the SNS curriculum.

References

Carreira, M. (2007). Spanish-for-native-speaker Matters: Narrowing the Latino Achievement Gap through Spanish Language Instruction Heritage Language Journal 5(1), 147- 171. Web.

COOK, V. (1999). Going Beyond the Native Speaker in Language Teaching. TESOL QUARTERLY, 33(2), 185-209.

Merino, B. J., Trueba, E. T., & Samaniego, F. A. (1993). Language and culture in learning : teaching Spanish to native speakers of Spanish. Washington, D.C.: Falmer Press.

Merriam, S. B. (2009). Qualitative research : a guide to design and implementation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

PEYTON, J. K., LEWELLING, V. W., & WINKE, P. (2001). Spanish for Spanish Speakers: Developing Dual Language Proficiency. Eric Digest. Web.

Teschner, R. V. (1987). Improving Language Learning for the Non-English-Language Native Speaker. Theory Into Practice, 26(4), 267.