Executive Summary

Standardisation is an outcome of globalisation. But some authors argue that these two are synonymous. With the advent of globalisation and the internationalisation of business, products were designed, demanded, sold, distributed and marketed the same way all throughout the world. It was known as the universal way of selling a product, the opening salvo of international marketing.

Changes evolved. Organisations have to introduce various changes in their marketing strategies, product orientation, employee management, and other organisational strategies. Cultural diversity is a trend in the age of globalization. Meanwhile, the demand for localized products is growing. Adaptation is one innovation that global organisations have to apply in their marketing strategies to adjust to cultural differences.

McDonald’s India is the main focus in our study of standardisation and adaptation. The company encountered problems and had to modify their organisational strategies because it had to adapt to a different kind of culture, a culture which recognizes cow meat as sacred, and Hindus are prohibited to eat beef. McDonald’s products are always western in origin, and when it came to penetrate foreign markets, it had to adapt to the cultures of the countries of destination. This is what they call adaptation, as opposed to standardisation of products.

McDonald’s India suffered rough sailing in the initial stages. Later on, it had to pause and reintroduce adapted strategies never forgetting that it was entering a delicate venture with a unique and diverse culture. How the company did it is a test of the company’s desire to succeed, and the primary focus of this paper.

However, there have been criticisms that McDonald’s do not apply diversity in its marketing strategy and that as an international organisation McDonald’s is an agent of globalisation. How true, we will find the answer by examining the ‘McDonaldisation’ of India, or the glocalisation of McDonald’s in the India market.

Introduction

How did the hamburger come to Asia? What is the difference between a McDonald’s hamburger served in India and a McDonald’s hamburger made in the USA or in the UK? These questions seem to just inhabit in the advertising campaigns of a company like McDonald’s or some other competitors, considering that global fast food chains sell whatever kinds of hamburgers people want. But these issues all point to the question of culture. The thing that we put in our mouths always reflects the culture that we have.

How did McDonald’s do it?

Thus, our first theory comes to fold: adaptation is coping with a culture of a country where an organisation operates. If an organisation wants to do business in a country with a different culture, it has to adapt. It always has to cope with the local culture. Cross-cultural aspects affect the people in the organisation, including organisational knowledge, marketing, product mix, etc. But international organisations have their own way of doing international marketing. Some do not believe in the dictum that they have to follow the political, social, technological, and legal environment in the country they want to penetrate. They only need to modify a little of their products and strategies, then they can dictate what they want.

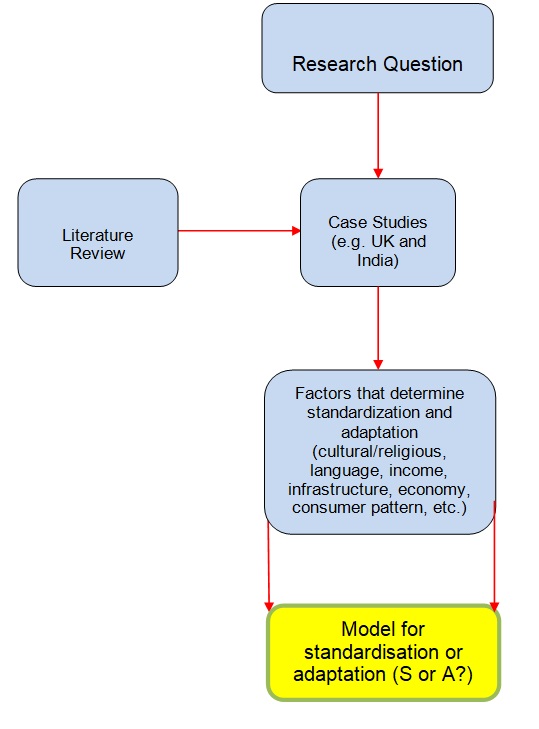

With these statements, our research question is presented: What are the various factors that affect the decision of a multinational company regarding whether it should have standardised products worldwide or an adaptation strategy to satisfy the local needs?

Methodology

Before the start of this research, this researcher has to decide what kind of data to be obtained (De Vaus, D., 2002). The term data refers to the kind of information the researcher obtains on the subjects of the research (Fraenkel and Wallen, 2006, p. 112).

The topic is on standardisation and adaptation which covers several underlying topics. We first focused on organisational theories, globalisation, international marketing and the various conceptions and theories of standardisation and adaptation of global firms. The vast information and data were sourced from the library, online and physical libraries, databases and websites. We narrowed down our research to McDonald’s India and McDonald’s UK regarding the subject of standardised products and products adopted to suit the taste and needs of the local population. The websites provide information about company mission, aims and objectives, along with their products, menus, employees and managers who have kept the companies running through the initial stages of the operation when they encountered problems pertaining to marketing in a diverse culture.

The methodologies applied are a mix of descriptive-analysis, the use of case studies, and analysis of the literature and secondary research conducted by authors and experts on the subject of marketing, standardisation and adaptation of products and other related topics. Our target audience for this research will be the students and academics of economics and management, prospective entrepreneurs who have planned to open up businesses in multi-diverse cultures in many parts of the world, and the business world in general who have thrived and strived in the age of globalisation. Our case study is focused on McDonald’s India as compared to McDonald’s UK.

Case Study Research

Case study research provides clear examples and explanations on the subject of standardisation and adaptation. Case study research was first designed by Yin (1981, 1984), and has since then been expounded and perfected by other authors and researchers. Selnick (1949, as cited in Eisenhardt, 1989, p. 534) introduced this in a study on TVA, and other similar studies and researches. Eisenhardt (1989) explained that the case study “is a research strategy which focuses on understanding the dynamics present within single settings” (p. 534).

Yin (1981, 1984) used the case study approach also defining it as a research strategy. But other authors have modified and added variations on the case study approach. Sutton and Callahan (1987 cited in Eisenhardt, 1989) introduced the Warwick group as a kind of devil’s advocate, while another technique by Eisenhardt (1989) made use of the cross-case analysis. Perfecting theories through case analysis were also studied and introduced by Van Maanen (1988), Jick (1979) and Mintzberg (1979).

In studying McDonald’s India, we gave preference on the country’s diverse culture. India does not only have one culture; it has a diversity of cultures. A great portion of the one billion people in India is comprised of Hindus who do not eat beef. Another part is composed of Muslims who, of course, do not eat pork.

At the start of the company’s plans to penetrate the India market, McDonald’s strategists dared to ask some questions: What would McDonald’s sell in India, the same products they sell in the UK? What kind of marketing strategy would they introduce in the country? These questions were playing in the minds of the pioneers of McDonald’s India and the local population at the time of the ‘hamburgerisation’ or ‘McDonaldization’ of India. But it all summed to the question of standardisation or adaptation. McDonald’s did succeed after a period of ‘turmoil’ and tests along the way. In a sense, their products are now part of India culture. McDonald’s ad on TV and other multi-media seemed to be a part of the Indian way of life. The western world has come to India.

In this paper, we have assumed that McDonald’s has succeeded in penetrating a country with a different cultural background, far different from the American and the UK way of life where fast food chains dominate, where hamburgers are a staple food and are eaten like they are the only food around. McDonald’s failed however in their initial venture, but they introduced new strategies and went on smooth sailing. At present, McDonald’s Corporation, as a global corporation with international branches, is one of the most successful fast-food chains in the world, and, particularly, in India.

McDonald’s outlets are franchises and they do give freedom to their managers on how to manage or run their respective businesses. Franchising is a strategic decision, and giving freedom to the managers has proven to be a success. (Strategic Direction, 2007)

How did McDonald’s India practice and introduce standardisation and adaptation? Which one did they adapt in the India market? When is the perfect time to adapt such strategies? The answers are narrowed down and explained in the study of the literature and analysis of McDonald’s India’s operations, and the ups and downs of international marketing.

Literature Review

In this section, we provide concepts and theories from the literature, definitions of standardisation and adaptation, including studies and researches of authors and experts in the field, and a theoretical framework for the case study of McDonald’s India and McDonald’s UK. We have divided this chapter into several subsections to provide a clear view of the subjects in question.

A remarkable gap between standardisation and adaptation is that it is still one of the controversial issues and has always been a subject of debate among international companies since 1961 (Vignali and Vrontis 1999; Elinder, 1961 cited in Vrontis et al., 2009). To date, international companies still battle over which one to choose.

There have been numerous studies conducted on these two subjects but it remains a hot topic for discussion (Vrontis et al., 2009). Vignali and Vrontis (1999 cited in Vrontis et al., 2009) stated that the debate started as far back as 1961 when advertising was one of the primary topics.

Multinational companies wanted to standardise advertising, and to further apply it to other promotional mix and marketing mix. Until now the debate whether to standardise marketing (or to adapt new products) remains a focal point for discussion (Schultz and Kitchen, 2000; Kanso and Kitchen, 2004; Kitchen and de Pelsmacker, 2004; Vrontis et al., 2009).

Ryans et al. (2003 cited in Vrontis et al., 2009, p. 478) pointed out that academic research on this subject has covered much of the literature on marketing. They pointed out that because of globalisation, there has been a surplus of exports over imports, prompting international companies to minimise cost of production. However, firms realised that it was necessary to answer or meet the needs and wants of consumers. Meeting the needs and wants of customers is a primary marketing strategy of international companies nowadays.

A study was conducted by Hite and Fraser in 1988 on whether firms used standardisation or adaptation in their international trade and business throughout many countries. The study utilised a sample of 418 Fortune 500 companies, and the findings were varied and, in fact, surprising. The respondents comprised of 66 percent international firms who advertised internationally, but of this percentage, only 8 percent patronised standardisation in advertising, with the rest using adaptation in their advertising campaign. The researchers also found that ninety-five percent of the respondents were united in saying that language is an important aspect of advertising and this should be used in the local advertising in introducing the scenes, models, backgrounds, etc., to the public. The conclusion of the study is that adaptation is an important strategy in accommodating cultural differences in the host country. (Baker, 2000, p. 23)

Standardisation

Standardisation sees the world as one entity with a common market (Herbig, 1998, p. 47). To have a standard product is to have the same product sold throughout the world. There are benefits for this, for instance, the production cost for the organisation is at the minimum. Economic benefit is one of the primary objectives of having a standardised product. A company does not have to spend much for research and development or add more expenses for the development of the product. Simply said, it is a standard product for anyone no matter what the culture or race is.

It is not only the product that is standardised, also the marketing. The basis for standardisation is the comparison of market strategies and operation in the country of origin, or the home market, to the market strategies in the country of destination. The target market must be known and well studied. (Chung, 2007, p. 145)

Proponents of standardisation argue that the key to long-lasting competitiveness is to standardise products (Fatt, 1967; Buzzell, 1968; Levitt, 1983; Yip, 1996; Vrontis et al., 2009, p. 478).

Outcomes of standardisation include economies of scale and the unification of markets. Many organisations, particularly those with global brands (for example, Coca Cola, Levi’s Jeans, etc.), prefer this strategy because of the savings attained (Czinkota and Ronkainen, 2007, p. 328). Some companies standardise their marketing strategies including advertising. An advertising slogan and promotion can be conducted in English with the same format and contents and to be shown on TV and multi-media in several countries.

Theodore Levitt (1983) discussed the “homogenization of markets” whereby consumers throughout the world tend to want the same kind of products whilst organisations will reach a point that they can build or manufacture the same kind of products with quality and sell them to the world at minimal costs (Levitt, 1983, p. 92). Many authors however argue that ‘pure’ standardisation is not possible. Somehow, the company has to modify some aspects or properties of the product or the strategy in order to sell.

The school of thought of standardisation emphasises that globalisation is the primary cause or the main driver of standardisation. Standardisation enables the company to conduct effective planning and control. The product brand image is enhanced and protected (Codita, 2011, p. 25). International companies are not focusing on brands that can be sold globally. (López, 2004)

Buzzell (2000, p. 103) defines multinational standardisation as “the offering of identical product lines at identical prices through identical distributions systems, supported by identical promotional programs, in several different countries… [and] completely ‘localized’ marketing strategies would contain no common elements whatsoever.”

Adaptation

Considered a reaction to standardisation is adaptation (Theodosiou and Katsikeas, 2001, p. 3, cited in Codita, 2011, p. 25). Advocates of adaptation school of thought argue that various factors affect the organisation and its marketing strategies. Culture, language, social, and other factors trigger adaptation as a method of selling products to other countries. (Codita, 2011, p. 25)

Firms find adapting to a new environment a difficult task. There are difficulties in adjusting to a new culture, as well as adapting to technical innovations (Henderson and Clark, 1990), or solving market crises (Haveman, 1992). Some organisations have made it successfully, but many have failed because of so-called inertial forces.

Knight (1921, 1965 cited in Kaplan, 2008, p. 729) argued that it is not the environmental forces that made the managers perceived it to be difficult, but their inability to assess the various changes taking place in the new environment. Moreover, “strategic action is influenced by how managers notice and interpret change and translate those perspectives into strategic choices” (Daft and Weick, 1984). This means it all depends on the manager’s skill and expertise to translate the changes into usable strategies.

“In many industries characterized by rapid technological development and intense competition, superior knowledge, rather than market power and positioning, is the key to long-term success” (Gupta and Becerra, 2003).

With intense globalisation, organisation structures have to evolve in response to geographical and market diversity. It is not anymore easy to change structures because changes in the organisation are based on complex environmental factors (Mead, 2005, p. 3). Companies need personnel and departments in order to grow in this so-called global village (Littrell and Salas, 2005). But companies and organisations also have to belt-tighten, lower operational costs and minimise expenses. What they need are more personnel with less costs for the hiring and training of these personnel. (Hitt et al., 2009, p. 23)

The question now is ‘when’ to standardize or to ‘adapt’ products and marketing strategies. What should companies apply when faced with such a dilemma?

Vrontis et al.’s (2009) study provides a compromise and wise answer to this question.

“The research has shown that on a tactical level (marketing mix) an either/or approach is unwise and one likely to damage businesses.” In other words, multinational companies should decide only after a careful study of the premises, and this should be added with some experience.

Vrontis et al. (2009, p. 482) adds: “International practitioners need to search for the balance between standardisation and adaptation as it is hypothesised that adaptation versus standardisation is not a dichotomous decision.”

Standardisation is preferable to adaptation when adaptation is expensive; when the market calls for industrial products only; when tastes or convergence are similar in different countries; when it is used commonly in urban markets; when management of a particular organisation is centralised; when R&D and development and marketing are not too costly; when other competitors are doing the same; and, if home image has a good standing internationally (Herbig, 1998, p. 39).

The situation calls for adaptation when technical standards differ; when products are for consumer or personal consumption; when consumer needs are not the same; when culture of buying and consumption are different; and when cultural differences call for adaptation. (Herbig, 1998, p. 39)

Globalisation drives Standardisation

Globalisation has triggered standardisation. It became a rallying point of international organisations at the advent of the internet or the World Wide Web. It has affected the political, economic, social, and even religious life of the peoples of the world (Herbig, 1998, p. 31).

The ‘old world’ is now dominated by information and communication structures brought about by technology and the internet. The ‘world of objectives’ is gradually replaced by ‘a world of signs’ (Bartelson, 2000, p. 189). This is the age of the digitisation of the world. In globalisation, nation states have lesser roles or in the words of Bairoch (2000), “the diminution of the role of states”.

Globalisation is also characterised by mergers and acquisitions and joint ventures of industrial, commercial and financial companies, leading to an increase in the global role of large, multinational companies and to a lessening of the role of nation-states. (Bairoch, 2000, p. 197)

Theorists like Held (2000, p. 55 cited in Raab et al., 2008, p. 597) and his colleagues conceptualise globalisation as “a process (or set of processes) which embodies a transformation in the spatial organization of social relations and transactions – assessed in terms of their extensity, intensity, velocity and impact – generating transcontinental or interregional flows and networks of activity, interaction, and the exercise of power.”

Globalisation is facing numerous challenges, such as protectionism, neo-liberalism, and complaints by groups against exploitation of human and natural resources by transnational corporations. Present remarkable innovations include the establishment of multilateral organisations such as the World Trade Organization (WTO), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank Group, and the rise of regional trade agreements.

Economically, proponents of globalisation expect it to increase growth, decrease inequality and poverty across people and countries. Politically, socially and culturally, they hope that it will decrease differences, reduce xenophobia and lead to a global consciousness where the nation state is no longer the main unit of identity for individuals.

Opponents of globalisation or those who oppose it for ideological reasons, argue that the socioeconomic costs of globalisation are too high and the benefits are inequitably distributed. Politically, they claim that globalisation has simply acted as a vehicle for American hegemony, and to a handful of powerful transnational corporations. (Giusta et al., 2006, p. xiii)

Held (1999, p. 2, as cited in Giusta et al., 2006, p. xiii) described globalisation as the “widening, deepening and speeding up of worldwide interconnectedness in all aspects of contemporary social life, from the cultural, the financial, to the spiritual.”

Other scholars interpret globalisation as the result of plans conceived by certain forces pursuing their selfish objectives. There are sceptics coming from many nationalities. The Russians view it “as coined by the modern information media, and is ambiguous, profoundly demagogical and fundamentally misleading” (Kagarlitski, 2001, cited in Rozanova, 2003, p. 51). In this sense, globalisation is an expression of the capitalist view because it attempts to impart objective character to reflect the positions of transnational corporations, which are trying to solidify their dominant position.

Other authors express it metaphorically by saying that the world is now living in a global village, narrowed down or has been made ‘small’ (but limitless) by the interconnectedness of things with the introduction of the internet or the World Wide Web. With technological innovations being introduced everyday relatively every minute of the day, computers are ordinary inventions. Today we can carry ‘mini computers’ within us like cell phones or such other new inventions. Communication is the most important discovery benefiting globalisation.

The question of identifying national borders on the internet is complicated by the fact that there is no clear agreement as to what ‘national borders’ are. Goodwin (1974, p. 100 cited in Halavais, 2000, p. 8) defines national border as “an imaginary boundary tied strictly to geographical territory in which a state’s sovereignty may be exercised”.

Global firms handle a large organisation but geographic consideration is different now. “It is the characteristics of globalisation rather than the territorial dimension that makes a difference” (Sussland, 2000, p. 2).

With globalisation, firms have to adjust to two cultures – local and international. This produced a dual brand of management. It is “… achieving global operation integration, synergies, and economies of scale, while at the same time remaining sensitive and responsive to local business conditions” (Bartlett and Ghoshal, 2002, cited in Vance 2006, p. 36).

Theodore Levitt says that “technological, social, and economic developments over the last two decades have combined to create a unified world marketplace in which companies must capture global-scale economies to remain competitive” (Bartlett and Ghoshal, 2002, p. 6).

With intense globalisation, there followed the emergence of multinational companies which has made our time phenomenal, ultra-modern, technology- and globally-oriented. The number of multinational corporations (MNCs) has risen. Triggers of the emergence of MNCs include the removal of trade barriers within regions (Buzzell, 2000, p. 102). Information Technology and the Internet also played a significant role.

The interdependence of nation states across boundaries has increased significantly. Organisations and businesses are now composed of managers and employees of different nationalities. From the phenomenal activities in business, problems have emerged, such as the marketing strategies that organisations have to implement in the countries of destination, or at the subsidiaries which are in foreign lands with different cultures, language, religion, and of course, food that the local inhabitants eat.

Organisations, no matter how big and how small, are affected by other organisations and businesses around the world. The attitudes, values and behaviours of the people within the organisation are affected by different cultures. Moreover, products too are affected by the multiplicity of cultures because customers also seek products that have the global or international look and appeal. (Briscoe and Schuler, 2004, p. 12)

Along with the internationalisation and standardisation of products is the question of marketing. With MNCs and globalisation, marketing follows. For example, as Buzzell (2000) asked, will there be uniform advertising approaches “on the grounds that fundamental consumer motives are essentially the same everywhere”?

The stakes are high for organisations joining the bandwagon in the international competition, and the costs are real extreme. Organisations commit blunders, others are not that quite good that they have to pack and go home. They have to execute intelligently and strategize their plans in order to succeed. (Oddou et al., 1995, p. 3)

Organisational Theories

Knowledge is significant in the study of international organisations, especially when we deal with international marketing research and the many aspects of organisational competitiveness. Knowledge is usually understood to mean theoretical knowledge, practical knowledge, experience, and skills. Knowledge and knowledge management are significant developments in the new globalising environment.

Tacit knowledge is that which an individual is not fully aware of, and which is difficult or impossible to explain in writing (Nelson and Winter 1982, cited in Fong et al., 2007, p. 40). Explicit knowledge is tangible and can be understood orally or in writing (Kogut and Zander 1992 cited in Fong et al., 2007, p. 40).

There are various kinds of organisational knowledge which can be found in the literature, for instance, scientific and practical, and those which are codified. The most frequently used is the one which distinguishes between tacit and explicit knowledge. (Rodriguez and de Pablos, 2000, p. 175)

In this study, the subject correlates with knowledge management, as marketing strategy with respect to standardisation and adaptation should be studied with a vast amount of knowledge. Managing knowledge is a key element in the achievement and sustainability of an organisation.

Knowledge management and the creation of knowledge are phases or steps very much present in the study of organisations. Knowledge management in the context of the physical place of an organisation draws one’s attention to the philosophy of ba, a concept originally proposed by the Japanese philosopher Kitaro Nishida (cited in Nonaka and Konno, 2008, p. 40). Knowledge is embedded in ba which is acquired through experience. When knowledge is separated from ba, it becomes information.

In the present age of globalisation, competitive advantage is more pronounced with the knowledge people possessed, or what is termed, ‘people-embodied knowhow’ (Rodriguez and de Pablos, 2002, p. 174). Tangible assets no longer provide concrete competitive advantages. Firms are focusing on what their people know, and invest much on intellectual capital.

There are barriers to knowledge sharing within the organisation and among the departments, sections, or branches of the organization. Szulanski (1996) termed this as the internal stickiness within the firm. Organisations usually apply and transfer best practices among themselves, or within the firm, but the barriers impede this transfer of knowledge from people to people, from department to department, or from branch to branch. Experiences of different organisation, like General Motors, IBM, etc, proved that it is not easy to transfer knowledge or best practice. Internal stickiness has been seen as an important topic of study.

According to Szulanski (1996, p. 28), practice means “the organization’s routine use of knowledge and often has a tacit component, embedded partly in individual skills and partly in collaborative social arrangements” (Nelson and Winter, 1982; Kogut and Zander, 1992). Transfer is used to connote “the movement of knowledge within the organization” (Szulanski, 1996) which can be seen as a unique learning experience for the individuals in the workplace or office.

Organisational Boundaries

The term ‘organisational boundary’ reflects what the organisation is all about. It is ‘”the essence of the organization” (Santos and Eisenhardt, 2005, p. 505). Organisational boundary also refers to “the demarcation between the organization and its environment” (Santos and Eisenhardt, p. 491).

Boundaries define the demarcation between an organisation and its environment and connote the uniqueness of the organisation, at the same time defining what is inside and outside of the organisation. Thus, the study of organisational boundaries tells us what is happening inside and outside the organisation and how we can relate to these two aspects of the demarcation lines. From this point, we can tell how an organisation exists, which makes our study of the organisation and the case study of McDonald’s India and UK more interesting. Through our understanding of boundaries, we can have a deeper understanding of organisations. (Santos and Eisenhardt, 2005, p. 505)

Boundaries have four concepts which are efficiency, power, competence, and identity. These concepts deal with organisational issues and connote the uniqueness of boundaries; for example, efficiency is about cost; power may reflect on autonomy; competence refers to growth; whilst, identity is about coherence. The four conceptions also foretell about horizontal and vertical boundaries. Horizontal speaks of the scope of the product and the target market whilst vertical boundaries tell of the scope of activities being undertaken within the industry. (Santos and Eisenhardt, 2005, p. 491-2)

The conceptions mean that the demarcation, which is the subject of boundaries, connotes the inside and the outside of the organisation. The conceptions also speak of strategic relevance within and outside the organisation and may also refer to competitive advantage.

Case Study: McDonald’s India

This section will examine how McDonald’s opened up in India, the marketing mix it applied, and the surrounding cultural problems and other significant issues that have arisen in its initial operations. How and when did McDonald’s India begin? What are the underlying factors for its establishment in a country whose people do not eat beef?

Unlike China, India is a democracy, with a population of more than a billion people. It is a socially diverse country with 20 spoken languages and hundreds of dialects. India spends about US$77 billion dollars annually for food alone. The predominant religion is Hinduism which fosters the belief that the cow is sacred, and thus beef is not to be eaten. (Rangnikar, n.d.)

McDonald’s now has an employee population of more than 2,500 trained personnel across India. (McDonald’s India, 2010)

McDonald’s India Marketing Mix

Instead of the usual hamburger with beef in between the slices of bread, McDonald’s offered the Maharaja Mac mutton-and-vegetable sandwich. This is a replacement of the Big Mac which fits the Indian appetite. (Biers and Jordan,1996)

In their first Indian outlet in New Delhi, they introduced their products with raw materials coming from Indian suppliers, and nothing came from abroad (Bolman and Deal, 2003, p. 56). McDonald’s India also introduced the veggie meal consisting of vegetables, salads, including ‘Chicken Mexican Wrap’, but excluding pork and beef.

Local suppliers are ‘trained’ and oriented to the quality and marketing strategies that McDonald’s has been using in other parts of the world, such as in the United States and the United Kingdom. Quality is first, and quality has to go with the strategy. The products are local, adapted to the taste of the Indian, but the orientation, the name, the brand, and the conception remain.

During its initial operations, it set up distribution centres and networked with distributors, partners and employees, to see to it that it met the quality and hygiene standards as required by the local community. The other menu consisted of chicken, mutton, fish and vegetarian burgers, added with Indian flavor. They have eliminated beef and pork, which are offensive to Indian and Muslim cultures, respectively. (McDonald’s India, 2010)

McDonald’s partnered with a well-known fruit and vegetable farmer, Mangesh Kumar of Ooctacamund in Tamil Nadu, who then supplied the company with iceberg lettuce. This partnership was guided by the company’s quest for quality produce and service. They asked Mr. Kumar to choose quality seeds and practice select farming methods to provide good products. Mr. Kumar became a model on this regard when he came to supply not only McDonald’s outlets in India but also to other parts of the world, such as the Middle East. Many other farmers followed the footsteps of Mr. Kumar in his partnership with McDonald’s. (India Business Intelligence, 1998)

McDonald’s also contacted Cremica Industries for the supply of bread; Cremica is a small company supplying bread to the local market of Phaillaur, Punjab. Cremica grew to become a partner of other international firms like Quaker Oats of the United States. Other companies which partnered with McDonald’s included AFL Logistics, a partner company of Air Freight, to handle the transport of products with the needed refrigerated vehicles for control of temperature of the products, and for delivery to regional distribution centers. McDonald’s partnered with local distributors and suppliers for its products which were tuned to the local culture and market. It also coped with the Indian culture and local legislations to stay in the business. (India Business Intelligence, 1998)

In the 1990s, the Indian economy was liberalized which paved the way for the entry of fast food chains. This also led to the change of the eating styles of the Indians.

Most Indians love home-cooked food, but with the increasing influence of western culture especially with the existence of food companies from the United States or the United Kingdom, urban Indian families have shifted from the traditional to modern patterns of food consumption.

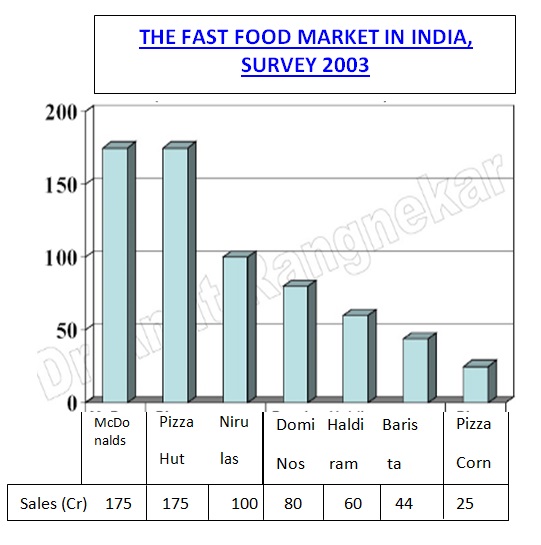

Fast food became so popular that the traditional way of eating home-cooked food was somehow affected. Fast food is very much patronized in India nowadays. (Goyal and Singh, 2007, p. 182) (See appendix for a comparison of McDonald’s India fast food chains and other fast-food companies in India. India was leading in 2003, and the recent surveys may prove the same results.)

To adapt to the Indians’ love for home-cooked food, McDonald’s introduced the McDelivery, delivering special economy menus for two or four persons and reaching to Indians who do not want to go out of their homes. (Gerbe, 2007, p.14)

A study was conducted on Indian young consumers aged 20-27 years old on their passion for visiting fast food chains McDonald’s and Nirula’s, another local fast-food chain in India. The results revealed that the young really had this passion although they still preferred home-cooked food. (Goyal and Singh, 2007)

McDonald’s first entered India with only 49% interest in the joint venture. The company had to give in to the political and legal requirements (Senatore, 2010). In 1996, McDonald’s Corporation (USA) started a joint venture with the leading restaurant corporations in India, namely Hardcastle Restaurants Pvt. Ltd, owned by Amit Jatia. This partnership now operates Western India. Another company owned by Vikram Bakshi who operates Connaught Plaza Restaurants Pvt. Ltd. has operational jurisdiction over Northern India. These restaurants have opened branches in Mumbai, Delhi, and other major states and cities in India. (Basu and Wright, 2008, p. 169)

More outlets were opened in Gujarat and Karnataka. Madison Public Relations took care of the PR, whose role was to “keep up the image of the brand, building advance awareness and expectation in places where it will open new restaurants… [and to] communicate promotions and new developments, as well as support marketing initiatives through PR where possible” (Gupta, 2006).

Not minding too much of its brand, McDonald’s offered ‘aloo tikka’ in Bombay. They used this technique of marketing having thought that consumers nowadays have become accustomed to brands that are close to their traditional menu, or close to home. This marketing strategy enabled the company to become one of the top 10 in the BusinessWeek / Interbrand ranking in 2003 over 100 best global brands. (Marketing Magazine, 2003)

It is obvious that McDonald’s could not have penetrated the India market without having diversified and adapted its products to satisfy local needs.

What went wrong to McDonald’s India?

McDonald’s made joint ventures with the restaurant leaders. However, there were some barriers to entry. At first, multinational companies were perceived as only serving chicken and did not serve vegetarian food. Fast food was also perceived as expensive and not in line with the Indian culture which was used to home-cooked food. The menus were also rich in fat, calories, and sugar. This was the reason why McDonald’s India did not get the desired customer support during its initial offering. The company encountered rough sailing.

Initially, there were no debates about McDonald’s entry in India over its hamburgers because the company adopted a strategy by offering fishburgers, veggie burgers, chicken burgers and salads, and other menus conducive to the Hindu taste (The Economist 1997). But in the first period of sailing, there were hitches, of course.

Something happened along the way which tested the expertise and skill of the marketing strategists of McDonald’s India. A worse scenario happened that needed a crisis management team for the young company in India. This team did it with expertise and success only those who knew the Indian psyche could do it.

In 2001, news came out in the United States that McDonald’s was doing what was entirely a taboo for the Hindu religion – that it had been using beef extract (or flavoring) in cooking its fries in the Indian outlets. This ‘big’ news for the India hamburger market reached the India national dailies on May 4, a day after it was relayed by U.S. newspapers. The Indian national dailies however reported that McDonald’s India outlets used no beef or pork flavoring in its fries and other vegetarian products. That added information failed to calm down local activists from demonstrating and showing their disgust over the Big Mac’s ‘irresponsible’ actions for its products. Cosmopolitan Mumbai local activists reacted quickly while those from the northern region of India waited for an explanation. Mumbai’s Thane outlet met fierce actions by fundamentalists who were always keen on McDonald’s presence in the country. There were pickets in outlets in Mumbai’s CST railway station, with activists doing the more prohibited reaction – throwing cow dung at the building. (Gupte, 2001)

Some outlets received peaceful actions; one was at the western city of Pune, which was saved because McDonald’s had provided media tours for its facilities a week before the U.S. news. The people there gladly received the assurance that there was no meat flavoring in their hamburgers.

With this bad news, McDonald’s used its crisis management machinery to calm down the Indian population and to take necessary steps. At that time, the company had an estimated 3.5 million customers for its outlets every month, and an 80 percent annual growth since it opened in 1996. McDonald’s local partners in India, Amit Jatia and Vikram Bakshi, were alarmed of the ongoing situation. The crisis management team was composed of local executives, aided by Amit Jatia and his staff, along with PR experts, advertising and corporate poeple and lawyers. They also asked security from the local police to secure the outlets. (Gupte, 2001)

Finally, they decided to first issue posters and ads of assurance that McDonald’s French fries were hundred percent vegetarian, and that they had used no flavors from pork or beef extracts for their products in India. The posters were published and pasted over all their India outlets. Jatia explained that their company had done nothing to hurt the India population, so that they could afford to tell the truth, and they had kept the lines of communication open for all to express their ideas. The crisis management team met with the press people, politicians, and they also supplied samples for laboratory testing. The samples of the fries were tested at the laboratories in Pune and Mumbai. Government and private organisations, such as the Council of Fair Business Practices, the Delhi’s Central Food and Technical Research Institute, were consulted. The Bombay Municipal Corporation did the laboratory tests.

Finally, after a week, the results showed that there was no meat flavoring in the oil used by McDonald’s. The results were passed on to the press and for everyone to know the truth. A packed press conference was assembled on May 5, with McDonald’s suppliers presenting to the public that they were certified that their products and ingredients were free of animal fats. Posters and press releases were passed on to the cities and communities with outlets. All’s well that ends well. The Big Mac was welcomed again in India. McDonald’s India partners had again stressed their vegetarian menus. (Gupte, 2001)

A Comparison of McDonald’s India and McDonald’s UK

Britain and India share a common history. The historic kingdoms of Scotland, Ireland and England and the subcontinent were influenced by the Mogul empire and the English East India Companies. The merchants of London were trading along the east point of the Cape of Good Hope (Lenman, 2002). Food was also influenced during this era, although the two cultures were always different.

McDonald’s Corporation established and ventured in the UK in 1974, and is now the leading fast-food market in the country (Royle, 1999, p. 135). McDonald’s UK’s menu from breakfast to dinner range from starchy foods to pork sausage patty to beef, and ingredients serve the best that the English or European palate can wish for. McDonald’s UK beef comes from British and Irish farm suppliers. They also use chicken breast meat instructing their suppliers to raise animals according to strict standards. Only exclusive cuts of pork are used. (McDonald’s UK, 2010)

McDonald’s continues to modify or change its product line to answer customer needs and wants. However, customers complain that some of their meals have high contents of fat, sugar, and salt. Criticisms continue that McDonald’s is not concerned of customers’ health when their meals do not mind health menaces such as obesity, heart disease, hypertension, etc. (Strategic Direction, 2007)

In both countries, India and the UK, McDonald’s use adaptation in their products and marketing strategy. However, in the UK some marketing strategies are standardised emanating from the home country, the United States.

Product Pricing

Price has a strategic element, since price shows how products become positioned against other products in the market. Undercutting competitors on price is a common way of competing. (Blythe, 2006, p. 447)

McDonald’s follows a different process of pricing but with a sense of similarity in its many branches throughout the world. It looks at the objective, the demand from the local community, the cost of the raw materials, and the competitors’ strategy. These factors are being considered in determining the final price for the product. Price of the Big Mac has marginal and comparative differences because McDonald’s determines the prices according to the individual’s ability to buy a Big Mac. McDonald’s thinks of the local population in determining their prices. (Vignali et al., 1999, cited in Groucutt et al., 2004, p. 479)

According to a survey of regional and intraregional pricing differences of McDonald’s, there are less differences in menu prices between company outlets and licensed stores throughout the UK, India, and the rest of the world. In other words, there is “divergence in both timing and magnitude of price increases among company stores” (Research Bernstein, 1978, p. 13).

Infrastructure

The UK infrastructure is more advanced and developed than that of India. Roads, bridges and buildings are built with more technology in the UK. It is where the industrial revolution started. Businesses and organisations thrive in the UK because of well-developed infrastructure. The people are accustomed to the modern way of life, with fast-food chains, restaurants and multinationals, many of which have American orientation.

In India, a great portion of the population is concentrated in the countryside or the rural area. The economy is growing, with the help of multinational corporations which need local labor supply for business process outsourcing (BPO) and call centers. When McDonald’s first ventured in India, they had to adapt to the Indian way of life, whose culture and religion are far different from the UK and American culture.

The Indian infrastructure has still to develop. Some authors and commentators group India with the rest of developing countries in Asia, or what they call Third World countries. India is behind the UK when it comes to development, but the former is a diverse and large market with low cost labour supply, and this is one of the reasons why big multinationals are eyeing India for their organisational expansion.

Cultural and Religious Issues

Lewis (2004) says that different cultures have different ways of resolving the problem, and good leadership in organisations makes cultural management successful. There are distinct differences between achievement-oriented cultures, which can be found in the US and the UK, and ascription cultures which can be found particularly in Asia, like India. In the former, performance is very much present in brands, while in the latter, products need to evoke admiration, for instance, technology or jewellery. A German will buy a Mercedes car for its engineering properties but an Indian will secure a Mercedes for its status. (Lewis, 2004)

Cultural differences always take a significant place in the introduction of products through the globalised world. This pertains whether to introduce products of global standards or local products. For some organisations, it is a question of global marketing initiatives, but for others it is something more than that. It may take the form of cultural management, or “how to manage across cultures” (Lewis, 2004).

McDonald’s UK products and menus have been adapted to the taste and culture of the British people. The English and American cultures have almost the same background, and this includes food. (Caputo, 1998, p. 48)

Majority of the population in the UK are Christians, but there is diversity of religions (Crabtree, 2007); unlike India where majority are Hindus. A hamburger made in the UK or the US is composed of sliced bread with a beef patty in between. In India, a hamburger has a different taste. Hindus do not eat beef for they regard cows as sacred, just as pork is not eaten by Muslims. India has a diversified culture, which paved the way for food diversity. A recent survey by Hindi-CNN-IBN (cited in Gerbe, 2007, p. 10), revealed that 40% of the Indian population adhere to the philosophy of vegetarianism. The culture dictates important family values, religion and family traditions.

Economy

India has a fast growing economy which has been triggered by its trade liberalisation. It survived the 2007-2009 recession and has kept a steady growth since then. Outsourcing by global firms is one of the major dollar earners in India. This is because English is one of the predominant languages. Global firms and companies looking for inexpensive outsourcing activities come to India. Many of these international firms are from the United Kingdom. However, in spite of the liberalization policies, there are more than 500 firms which are still under control by the government. (Economy Watch, 2009)

On the other hand, the UK economy was once the number one economy in the world in the days of the British Empire. However, its economy has recently declined. Many of the firms, particularly those situated in London, are global firms. The UK economy recently earned a budget deficit, with big public debts, and inflation and unemployment still rising. The year 2010 registered a negative growth for the UK. (Economy Watch, 2010)

Comparing the two economies, India and UK, would mean a comparison of contrasts. India is a large market and is still growing. The UK’s GDP has negative growth for 2010.

Income of the People

The following is a summary of the income distribution in India, which can provide a brief description of the needed India infrastructure for McDonald’s hamburger business.

Table 1. Income classification of the people of India.

SOURCE: Condensed from: Golden Arches: Case of Strategic Adaptation, by Dr. Amit Rangnikar (See appendices 2a and 2b for a graph presentation of this table).

A big portion of the Indian population lives below the poverty line. This is because the population has passed the 1 billion mark and could probably be growing if the government does not do some drastic action.

In contrast, the UK has 61 million people (Economy Watch, 2010), and although its economy suffered setbacks in recent years, it is still considered one of the richest countries in the world. There are many pensioners in Great Britain. Pensioners’ incomes have gone up, with net income also increasing. In 2003-2004, people aged 50-59 had a net household income greater than people aged 80 and above. (Office for National Statistics, 2011)

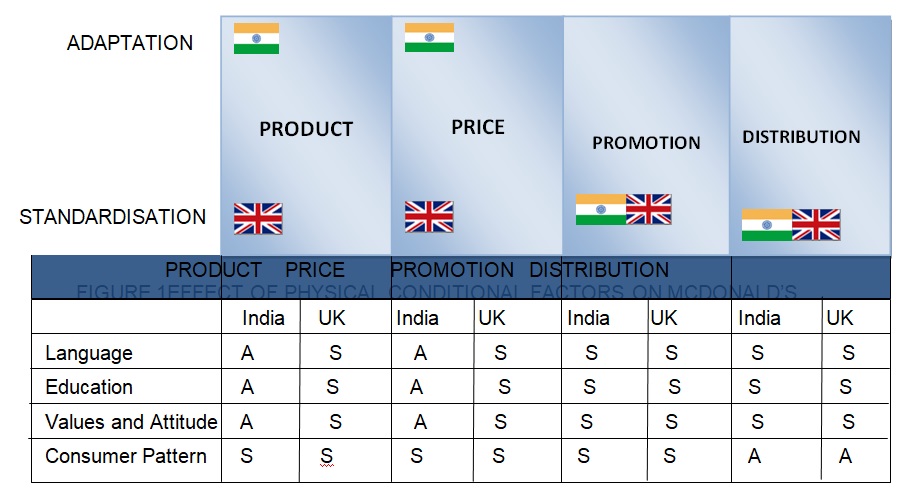

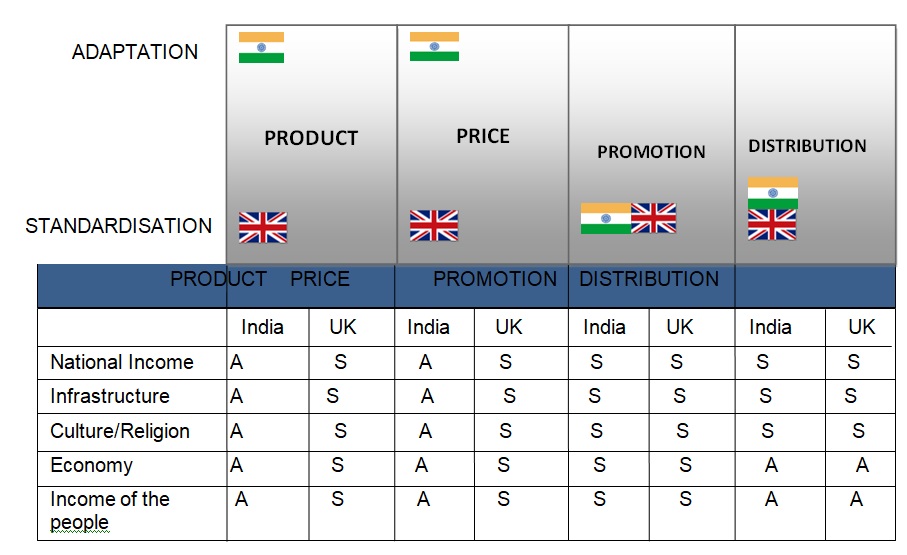

McDonald’s marketing mix is influenced by several factors. A comparison of McDonald’s India and UK shows that both use two kinds of strategy, standardisation and adaptation. We can tell this from figures 1 and 2.

Model for Multinationals

The main concern of this study is the question: What are the various factors that affect the decision of a multinational company regarding whether it should have standardised products worldwide or have an adaptation strategy for the product to satisfy the local needs?

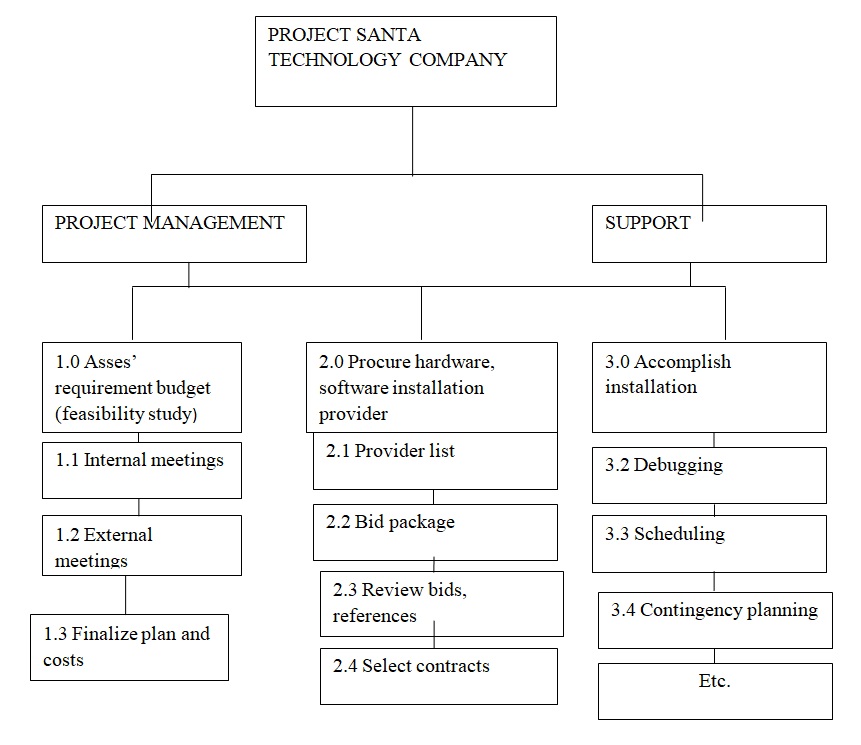

This question is expressed in the diagram below.

Conclusions

Standardisation and adaptation of products and marketing mix and strategies have remained a hot issue and a point for discussion among multinational corporations. This is the gap that has been pointed out from the beginning of this study. The debate continues.

First of all, it has been pointed out in this paper that culture plays an important role on whether the company should standardise the products or have adapted products to satisfy local needs. The literature on McDonald’s India can give us bright insights and conclusion that, indeed, McDonald’s Corporation could not have penetrated successfully the India market without adapting to the Indian culture and the Indian way of life. McDonald’s products have been diversified to suit to the Indian culture and taste. The company has made it a point not to commit slight errors or blunders in its operations. An incident happened when bad news from the United States media came out that McDonald’s India was using cooking oil from beef extract. McDonald’s management had to assemble its best ‘trouble shooter’ and crisis management in order to resolve the issue, and to reassure the Indian consumers that McDonald’s was not using any oil coming from beef or pork.

The McDonald’s chain of restaurants throughout the world uses standardisation in its marketing strategies but modifies, or adapts, its products using local menus and raw materials to satisfy local culture. The company has not only applied this in India but all throughout its many branches. In France, for example, the menu is translated into five languages and menu items there are unique compared to the United Kingdom and India (Mok, 2000, p. 272). But other authors like Karen DeBres (2005) noted that McDonald’s would try to change the local cultures to meet its own needs.

Managerial Implications

Based on the case study of McDonald’s India and McDonald’s UK, and from the literature, there are a number of managerial implications that should be considered when multinational companies want to venture into other countries with different cultures.

- International marketing concerns with working out with the localisation of products that suit to the customer’s needs and culture;

- Globalisation with standardised products does not work when culture is the main issue; the company has to adapt to the local culture;

- There is a homogenization of markets because the world tends to want the same kind of products and organizations can manufacture these products with quality and sell them at minimal costs (Levitt, 1983, p. 92).

- Pure standardization is not possible; products have to be modified in order to sell.

- Standardisation enables the company to conduct effective planning and control. The product brand image is enhanced and protected. (Codita, 2011, p. 25)

- The basis for standardisation is the comparison of market strategies and operation in the country of origin, or the home market, to the market strategies in the country of destination. (Chung, 2007, p. 145)

- Meeting the needs and wants of customers is a primary marketing strategy of international companies nowadays.

Calls for Further Research

This section will cover some of the points discussed in the dissertation but still needs further research and discussion. The study of McDonald’s India and McDonald’s India provided us with theoretical examples and the advantages and disadvantages of standardisation and adaptation.

McDonald’s India adapted their menus to the local culture. But the strategy needs to be further studied and tested considering that the company failed in its initial offering. The management still needs time and a long way before it can be said that their adapted products have succeeded.

Franchises for McDonald’s outlets proved to be successful it still has to be seen. From the start of the joint venture, McDonald’s demanded or asked its suppliers to provide quality products for the local franchises. But this has some drawbacks, considering that quality may suffer because of the freedom given to suppliers and the managers. The strategy of franchising McDonald’s outlets in India has to be given more studies and researches.

Shortcomings/Limitations

There were some shortcomings that this Researcher faced in the course of the Research and gathering vital information from the literature. One of these is linking the theories and vast information to McDonald’s strategies and marketing mix as they apply to McDonald’s India and McDonald’s UK.

We can easily conclude that McDonald’s has diversified and used adaptation in its products to satisfy local needs. But there are arguments that McDonald’s does not diversify. It just alters a bit of its products and strategies and enforces what it wants to sell to the local market.

George Ritzer’s book The McDonaldization of Society also brings to light how the company McDonald’s from the United States has penetrated and influenced society and the world (Alfino et al., 1998, p. xvii). No matter what the management of McDonald’s say that they have diversified and ‘followed’ the taste and culture of a particular country they are in, it still points to the belief that McDonald’s products have influenced the taste of peoples around the world, and not the culture of a country has altered McDonald’s products.

This study is applicable to other industries and international firms. Companies should diversify and adapt their products and strategies whenever they enter a country to conduct business. Although globalisation has made our world a ‘global village’, organisations have to deal with diverse and unique worlds. Marketing strategies and product diversities cannot be successful without management of cultural integration.

References

Alfino, M. et al., 1998. McDonaldization revisited: critical essays on consumer culture. United States of America: Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc.

Bairoch, P., 2000. The constituent economic principles of globalization in historical perspective: myths and realities (trans. by M. Kendall and S. Kendall). International Sociology June 2000, Vol 15(2): 197-214. Web.

Baker, M., 2000. International marketing communications explained. In S. Monye, Ed., The handbook of international marketing communications, pp. 23-4. United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

Bartelson, J., 2000. Three concepts of globalization. International Sociology 2000; 15; 180-193. Web.

Bartlett, C. A. and Ghoshal, S., 2002. Managing across borders: the transnational solution. United States of America: Harvard Business School Press.

Basu, R. and Wright, J. N., 2008. Total supply chain management. United Kingdom: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Bernstein Research, 1978. Extend and implications of regional and intraregional pricing for McDonald’s. Black Book – Restaurant Industry Trends [e-journal], Available through: City University London.

Biers, D. and Jordan, M., 1996. McDonald’s in India decides the Big Mac is not a sacred cow. Wall Street Journal [e-journal], Available through: Staffordshire University Library.

Blythe, J., 2006. Principles & practice of marketing. London: Thomson Learning.

Bolman, L. and Deal, T., 2003. Reframing organizations: artistry, choice, and leadership (third edition). San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Briscoe, D. and Schuler, R., 2004. International human resource management second edition (Routledge global human resource management series). UK: Routledge.

Buzzell, R., 1968. Can you standardize multinational marketing? Harvard Business Review, Vol. 46, pp. 102-103. Cited in Vrontis, D. et al., 2009, International marketing adaptation versus standardisation of multinational companies, International Marketing Review, Vol. 26 Nos 4/5 [e-journal], Available through: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Buzzell, R., 2000. Can you standardize multinational marketing? Harvard Business Review [e-journal], Available through: Staffordshire University Library.

Caputo, J., 1998. The rhetoric of McDonaldization: a social semiotic perspective. In: M. Alfino et al., Eds., McDonaldization revisited: critical essays on consumer culture, p. 48. United States of America: Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc.

Chung, H., 2007. International marketing standardisation strategies analysis: a cross-national investigation. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing, Vol. 19 No. 2, pp. 145-67. Available through: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Codita, R., 2011. Contingency factors of marketing-mix standardization: German consumer goods companies in Central and Eastern Europe. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer.

Crabtree, V., 2007. Religion in the United Kingdom: diversity, trends and decline. Web.

Czinkota, M. and Ronkainen, I., 2007. International marketing, 8th edition. United States of America: Thomson Southwestern.

Daft, R. and Weick, K. 1984. Toward a model of organizations as interpretation systems. Acad. Management Rev. 9(2) 284–295. Cited in Kaplan, S., Framing contests: strategy making under uncertainty, Organization Science, Vol. 19, No. 5, 2008, pp. 729-752. Web.

DeBres, K., 2005. Burgers for Britain: A cultural geography of McDonald’s UK. Journal of Cultural Geography; Vol. 22 Issue: number 2 p115-139 [e-journal], Available through City University London.

De Vaus, D., 2002. Surveys in social research (5th Edition). Oxon: Taylor & Francis Group.

Economy Watch, 2009. Indian economy overview. Web.

Economy Watch, 2010. UK economy. Web.

Eisenhardt, K., 1989. Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, Vol. 14. 532-550 [e-journal], Available through: City University London Library.

Elinder, E., 1961. How international can advertising be? International Advertiser December, pp. 12-16. Cited in Vrontis, D. et al., 2009, International marketing adaptation versus standardisation of multinational companies. International Marketing Review, Vol. 26 Nos 4/5 [e-journal], Available through: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Fatt, A., 1967. The danger of local international advertising. Journal of Marketing, Vol. 31, No. 1. Cited in Vrontis, D. et al., 2009, International marketing adaptation versus standardisation of multinational companies, International Marketing Review, Vol. 26 Nos 4/5 [e-journal], Available through: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Fong, P. et al., 2007. Dynamic knowledge creation through value management teams. Journal of Management in Engineering, Vol. 23, No. 1. Web.

Fraenkel, J. and Wallen, N., 2006. How to design and evaluate research in education (sixth edition). New York: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.

Gerbe, K., 2007. Intercultural communication as a strategy of global marketing: marketing strategies of McDonald’s in India and Saudi Arabia. Germany: GRIN, Verlag.

Giusta, M. D., et al., Eds., 2006. Critical Perspectives on Globalization: The Globalization of the World Economy. UK: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited. pp. xii-xiii.

Goyal, A. and Singh, N., 2007. Consumer perception about fast food in India: an exploratory study, British Food Journal, [e-journal], Available through: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. Web.

Groucutt, J., et al., 2004. Marketing: essential, principles, new realities. London, UK; VA, USA: Kogan Page, Ltd.

Gupta, D., 2006. McDonald’s India taps Madison. Business Source Premiere [e-journal], Available through: Staffordshire University Library.

Gupta, A. K. and Becerra, M., 2003. Impact of strategic context and inter-unit trust on knowledge flows within the multinational corporation. In B. McKern (Ed.), Managing the Global Network Corporation. New York: Routledge.

Gupte, S., 2001. McDonald’s averts a crisis. Ad Age Global, Jul2001, Vol. 1, Issue 11 [e-journal], Available through: Staffordshire University Library.

Halavais, A., 2000. National borders on the World Wide Web. New Media Society, 2; 7-8. Sage Publications. Web.

Haveman, H. A. 1992. Between a rock and a hard place: Organizational change and performance under conditions of fundamental environmental transformation. Admin. Sci. Quart. 37(1) 48–76. Cited in: Kaplan, Framing contests: strategy making under uncertainty, Organization Science, Vol. 19, No. 5, pp. 729-752. Web.

Henderson, R. and Clark, K., 1990. Architectural innovation: The reconfiguration of existing product technologies and the failure of established firms. Admin. Sci. Quart. 35(1) 9–30. Available through City University London Library.

Herbig, P., 1998. Handbook of cross-cultural marketing. New York: The Haworth Press, Inc.

Hitt, M., et al., 2009. Strategic management: concepts and cases. OH, USA: South-Western Cengage Learning.

India Business Intelligence, 1998. McDonald’s grows a supply chain. The Economist Intelligence Unit Ltd. [e-journal], Available through: City University London.

Jick, T., 1979. Mixing qualitative and quantitative methods: Triangulation in action. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24, 602-611. Cited in Eisenhardt, K., 1989, Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, Vol. 14. 532-550 [e-journal], Available through: City University London Library.

Jobber, D. & Lancaster. G., 2003. Selling and sales management, 6th edition. London: Prentice-Hall.

Kanso, A. and Kitchen, P. J., 2004. Marketing consumer services internationally: localisation and standardisation revisited, Marketing Intelligence and Planning, Vol. 22 No. 2. Cited in Vrontis, D. et al., 2009, International marketing adaptation versus standardisation of multinational companies. International Marketing Review, Vol. 26 Nos 4/5 [e-journal], Available through: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Kaplan, S., 2008. Framing contests: strategy making under uncertainty. Organization Science, Vol. 19, No. 5, pp. 729-752. Web.

Kitchen, P. and de Pelsmacker, P., 2004. Integrated Marketing Communications: A Primer. London: Routledge. Cited in Vrontis, D. et al., 2009, International marketing adaptation versus standardisation of multinational companies. International Marketing Review, Vol. 26 Nos 4/5 [e-journal], Available through: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Kogut, B. and U. Zander (1992). ‘Knowledge of the firm, combinative capabilities and the replication of technology’, Organization Science, 3(3), pp. 383-397.

Lenman, B. P. “Britain and India.” A Companion to Eighteenth-Century Britain. Dickinson, H. T. Blackwell Publishing, 2002. Blackwell Reference Online. Web.

Levitt, T., 1983. The marketing imagination. United States of America: The Free Press.

Lewis, E., 2004. Hamburger culture. Brand Strategy [e-journal], Available through: Staffordshire University Library.

Littrell, L. and Salas, E., 2005. A review of cross-cultural training: best practices, guidelines, and research needs. Human Resource Development Review, 4: 305. Web.

López, N., 2004. Marketing Mix and the internet: globalisation or adaptation? Journal of Euromarketing, Vol. 13, Issue 4, [e-journal], Available through: City University London.

Mead, R., 2005. International management: cross-cultural dimensions. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing.

Marketing Magazine, 2003. The cultural edge. [e-journal], Available through: Staffordshire University Library, Business Source Premier database.

McDonald’s India, 2010. Extra value mean: Mc veggie meal. Web.

McDonald’s UK, 2010. About us. Web.

Mintzberg, H., 1979. An emerging strategy of “direct” research. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24, 580-589. Cited in Eisenhardt, K., 1989, Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 1989, Vol. 14. 532-550 [e-journal], Available through: City University London Library.

Mok, C., 2000. Cross-cultural issues in service quality. In: J. Kandampully, C. Mok, & B. Sparks, Eds., Service quality in management in hospitality, tourism, and leisure, pp. 272-3. New York: Haworth Press, Inc.

Nonaka, I. and Konno, N., 2008. The concept of “ba”: building a foundation for knowledge creation. California Management Review, Vo. 40, No. 3, 2008.

Office for National Statistics, 2011. Income, wealth and expenditure. Web.

Oddou, G. et al., 1995. Internationalizing managers: expatriation and other strategies. In: J. Selmer, ed. New ideas for international business. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc.

Raab, M., et al., 2008. Global Index: a sociological approach to globalization measurement. International Sociology 2008; 23(4); 596-631. Web.

Rangnikar, A., n.d. Golden arches: case of strategic adaptation. Web.

Rodriguez, J. and de Pablos, P. O., 2002. Strategic human resource management: an organisational learning perspective. International Journal of Human Resources Development and Management, Vol. 2, Numbers 3-4/2002, pp. 175-6.

Rosanova, J., 2003. Russia in the context of globalization. Current Sociology, Vol. 51(6): 649-669 SAGE Publications. Web.

Royle, T., 1999. The reluctant bargainers? McDonald’s, unions and pay determination in Germany and the UK. Industrial Relations Journal 30:2 [e-journal], Available through: City University London.

Ryans, J. et al., 2003. Standardization/adaptation of international strategy: necessary conditions for the advancement of knowledge. International Marketing Review, Vol. 20, No. 6, pp. 588-603. Cited in Vrontis, D. et al., 2009, International marketing adaptation versus standardisation of multinational companies. International Marketing Review, Vol. 26 Nos 4/5 [e-journal], Available through: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Santos, F. and Eisenhardt, K., 2005. Organizational boundaries and theories of organization. Organization Science, Vol. 16, No. 5, [e-journal], Available through: City University London.

Senatore, S., 2010. McDonald’s Corporation at Sanford C. Bernstein Strategic Decisions Conference, Fair Disclosure wire (Quarterly earnings Reports) [e-journal], Available through: City University London.

Schultz, D. and Kitchen, P., 2000. Communicating globally: an integrated marketing approach. Cited in Vrontis, D. et al., 2009, International marketing adaptation versus standardisation of multinational companies. International Marketing Review, Vol. 26 Nos 4/5 [e-journal], Available through: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Smith, P. R. and Taylor, J., 2004. Marketing communications: an integrated approach 4th ed. United Kingdom: Kogan Page Limited.

Strategic Direction, 2007. McDonald’s is making changes to reflect modern tastes and working practices but are these enough to stem criticisms of the firm as an agent of globalisation? Strategic Direction, Vol. 23, No. 11 2007 [e-journal], Available through Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Sussland, W. A. 2000. Connected: a global approach to managing complexity. London: Business Press.

Sutton, R., & Callahan, A., 1987. The stigma of bankruptcy: spoiled organizational image and its management. Academy of Management Journal, 30, 405-436. Cited in Eisenhardt, K., 1989, Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 1989, Vol. 14. 532-550 [e-journal], Available through: City University London Library.

Sweney, M., 2004. McDonald’s bows to critics over salad dressing. Marketing [e-journal], Available through: Staffordshire University Library, Business Source Premier.

Szulanski, G., 1996. Exploring internal stickiness: impediments to the transfer of best practice within the firm. Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 17(Winter Special Issue), 27-43 (1996), [e-journal], Available through: Staffordshire University Library.

The Economist, 1997. As hamburger goes, so goes America? The Economist [e-journal], Available through: City University London.

Vance, C. M., 2006. Strategic upstream and downstream considerations for effective global performance management. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management 2006, Vol 6(1): 37–56. Web.

Van Maanen, J., 1988. Tales of the field: On writing ethnography.Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Cited in Eisenhardt, K., 1989, Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 1989, Vol. 14. 532-550 [e-journal], Available through: City University London Library.

Vignali, C. and Vrontis, D. 1999. An international marketing reader. The Manchester Metropolitan University, Manchester. Cited in Vrontis, D. et al., 2009, International marketing adaptation versus standardisation of multinational companies. International Marketing Review, Vol. 26 Nos 4/5 [e-journal], Available through: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Vrontis, D. and Thrassou, A., 2007. Adaptation vs standardisation in international marketing – the country-of-origin effect. Journal of Innovative Marketing, Vol. 3 No. 4, pp. 7-21. Cited in Vrontis, D. et al., 2009, International marketing adaptation versus standardisation of multinational companies, International Marketing Review, Vol. 26 Nos 4/5 [e-journal].

Vrontis, D. et al., 2009. International marketing adaptation versus standardisation of multinational companies. International Marketing Review, Vol. 26 Nos 4/5 [e-journal], Available through: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Weitz, B. A. and Wensley, R., 2006. Handbook of marketing. London: Sage.

Wright, P. et al., 2007. Human resources and the resource-based view of the firm. In: R. Schuler and S. Jackson (Eds.), Strategic Human Resource Management, pp. 76-80. UK: Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

Yin, R., 1981. The case study crisis: Some answers. Administrative Science Quarterly, 26, 58-65. Available through: Staffordshire University Library.

Yip, G., 1996. Toward a new global strategy. Chief Executive Journal, Vol. 110, pp. 66-7. Cited in Vrontis, D. et al., 2009, International marketing adaptation versus standardisation of multinational companies. International Marketing Review, Vol. 26 Nos 4/5 [e-journal], Available through: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2a

The two graphs (Appendices 3a and 3b) are an interpretation of the income distribution of the people of India. This is translated in two graphs where the classification, whether ‘deprived’ or ‘rich’ or ‘super rich’ has a corresponding income in dollars.

Appendix 2b