Introduction

Penology is defined as the process of restoring a convict to a useful capacity or reestablishing his person in the esteem of others. The key to the successful reentry of ex-offenders into the community is transitional employment, for which reason programs of all kinds and design have been established to secure a job for these people soon after their release from prison (Uggen, 2000). This is considered the most critical period in the effort to reintegrate ex-offenders into society based on the assumption that once honest work, albeit provisional, gave them that sense of self-respect that it usually bestows and they perceive that the workplace also has a place for those carrying the stigma of prison, they would then lead their lives avoiding crime in pursuit of employment. However, securing employment for ex-offenders is a formidable task precisely because of this stigmatization, such that the problem of recidivism continues to haunt the criminal justice system. This area of concern in the more socially oriented penology system of today has expanded from offenders who have been sentenced to serve prison sentences to those placed under regular probation and the special form of court-ordered resolution of criminal cases called deferred adjudication (DA). Statistics show that offenders on probation and on DA supervision far outnumber those committed to prison. In 2001, for example, there were 1,470,045 inmates in federal and state prisons in the US whereas there were 6.9 million offenders on probation (Freeman, 2003). The number of those on DA is more than 10 times larger. In Texas alone, there were 1,927,748 offenders on DA in 2005 (Bradley, 2006). The DA process is part of the criminal justice system in almost of the American states, including the commonwealths Hawaii and Puerto Rico. The problem is that while a DA decision of the courts is not considered a conviction, it is treated as such by banks, insurance firms, schools, law enforcement agencies, apartment leasing managers, and by society as whole. Thus, offenders on probation and DA face the same barriers to employment as the convicts who served time in prison.

This paper took up the growing literature on the need to provide employment assistance to offenders as a strategy to reduce the incidence of recidivism. A critical review and appraisal was made of transitional jobs reentry programs for convicts to determine which methods and strategies work and which do not. We looked into the research methodologies used in the literature to correctly predict recidivism so that the appropriate job search assistance can be initiated. The study indicated that some forms of measurement and assistance help for certain types of offenders under particular conditions but, overall, the consensus that emerged is that this kind of program still has a long way to go before the benefits of employment can satisfactorily address the growing problem of recidivism.

Research shows that ex-convicts who are gainfully employed are less likely to return to jail (State Progress, 2007), thus reinforcing the view that employment for ex-prisoners yields tremendous benefits to society by reducing the chances for recidivism. This makes employment the key that could unlock a solution to the perennial problem of recidivism, the primary reason for prison congestion and overcrowding. However, individuals with criminal or arrest records face formidable challenges in finding employment, which challenges actually jeopardize public safety by contributing to recidivism (State Progress, 2007). There are also the incalculable economic costs that accrue from recidivism because of the need to allocate endless funds for the upkeep and maintenance of prisons. To address the problem of recidivism, many state and local programs have been devised but there is little evidence that the strategies they employ achieve meaningful outcomes (MDRC, 2007). This paper sizes up the problem of recidivism, and discusses its causes and effects together with the potentials of employment to ease if not eliminate the problem. For this purpose, several reentry programs have been subjected to critical review and evaluation with the end in view of finding what reentry strategies are appropriate in the present context.

Offenders contend with more or less the same multiple barriers to obtaining and maintaining employment that other chronically underemployed people face, such as limited childcare, poor health and education, lack of employable skills and the means to make themselves presentable to employers (Murphy, 1999, p. 25). The challenges are compounded several times over for ex-offenders because of the social stigma attached to them, which has the potential to limit their entry at initial employment, threaten their sustained employment, and endanger their successful community transition (Farrington, et al., p. 18). This paper aims to discuss the employment-related dilemma faced by offenders on penal supervision and how their employment status as ex-convicts determines their success on supervised settings and the possibility of their re-offending.

Literature Review

Determining the proper response to the re-offending behavior of criminals has plagued governments, criminologists, the judiciary and the community for quite some time (Andrews, 1995, pp. 4-45). A precise figure for the rate of recidivism cannot be ascertained, since a substantial amount of crime that may be a repeat offense often goes unreported for one reason or another, and the courts do not convict all offenders for various reasons, including lack of evidence and legal technicalities. The rates of recidivism also depend on what measures are used in terms of the time frame considered and whether one is concerned about particular offenses, re-arrest rates or re-imprisonment. Notwithstanding the absence of a reliable figure, the rates could be high enough to cause alarm among penology authorities. There is a wide range of factors that contributes to the re-offending behavior of an individual offender, of which poor education and employment history, inborn deficiencies in mental and physical health, and drug and alcohol abuse are only a few (Gendreau, et al., 1996).

The effects of incarceration and jail sentences on recidivism constitute an important issue to those concerned with public safety and the cost-effectiveness of putting convicted offenders in prison because of the heavy social and economic costs of recidivism. In the desire to avoid these costs and promote public interest, opinion is divided between those who advocate longer sentences and those who favor shorter prison sentences (Austin, 1986, p. 7). The first view maintains that the longer the sentence, the better its reformative effect since this amounts to a harsher penalty that offenders may not want to undergo again (Sims & O’Connell, 1985) and thus avoid recidivism upon their release. As for penologists who hold the contrary view, they cite empirical evidence showing that longer prison terms never bring down recidivism rates. This paper in its evaluation of the theories and empirical studies on this issue finds that the effects of incarceration as against other sentencing options, as well as the sentence length on recidivism, is a complex subject and is likely to be offender-specific. For some offenders, incarceration and longer confinement seem to increase the risk of recidivism, while for other offenders, the likelihood of re-offense will either be unaffected or reduced by longer terms of incarceration. Furthermore, early-release programs do not appear to affect overall recidivism rates (Beck & Shipley, 1989).

Employment is universally recognized as highly capable of reducing the incidence of recidivism but the problem is that there is no harder task than finding employment for offenders such that unemployment has become strongly associated with recidivism (Farrington et al., 1986, pp.335). Evidence shows that if offenders are at work, this reduces their likelihood of re-offending (Farrington et al., 1986, pp.336; Gendreau et al., 1998, p.3). For this reason, the effort to secure employment for offenders is also a legitimate concern for those involved in reducing unemployment and social exclusion for the marginalized sectors of society. Offenders themselves acknowledge that any assistance that helps them land a job upon their release from prison is instrumental in helping them avoid re-offending (Gillis et al, 1996, p.1). There is a note of optimism in the reviews conducted in the last 15 years that effective employment-focused interventions can reduce recidivism, although policymakers are cautioned that not all interventions work equally well (Lipsey, 1995, p.20). McGuire (1995) believes that what is needed is a more specific understanding of what works and for whom, with attention focused more on the benefits of employment and less on the goal to reduce the incidence of recidivism.

In general terms, recidivism is defined as a return to criminal activity after a previous criminal involvement. The nature of the criminal activity committed by an offender may not be known but the predictors or indicators of subsequent criminal activity are often used to estimate the rates of recidivism. Some of these indicators are re-arrest, conviction, probation or parole revocation, and recommitment to incarceration. To calculate a recidivism rate, a group of individuals exposed to a treatment or sanction are followed over an appropriate period of time (Langan & Levin, 2002). The number of offenders that “fails” within that specified time period is divided by the total number in the group, which then becomes the basis for determining the recidivism rate. Offenders believed to be at higher risk for recidivism are then placed on community supervision or adult probation and assisted in finding transitional employment. The typical follow-up period for offenders in the criminal justice system is three years, which is considered the critical period when the largest percentages of offenders who are likely to recidivate actually do so (MDRC, 2007).

Bartell & Winfree, Jr. (1977, pp.387-395) analyzed the reconviction rates of 100 offenders convicted of burglary in 1971 in New Mexico and found that of this number of offenders, 34 were imprisoned, 45 were granted probation, and 21 were given other sentences, such as fines, drug and alcohol treatment and community services. After statistically controlling for differences in age, prior criminal history, and type of burglary, the findings indicated that offenders who were placed on probation were less likely to be reconvicted than those who were incarcerated. This means that the lighter punishment represented by probation is more effective in reforming offenders than incarceration. While the dramatic increase in the number of men and women incarcerated in state and federal prisons in the US over the last 10 years has become a matter of common knowledge, a less recognized but perhaps more alarming phenomenon is the growing number of individuals who return to their neighborhoods after serving a prison term ill-prepared for the process of reestablishing their lives. The Department of Justice estimates that about 600,000 of such individuals come out of federal and state prisons annually and released to communities across the nation (Beck & Shipley, 1989). During one conference on restorative justice, a promotional flyer was prominently displayed at the venue, which captured the essence of the problem confronting ex-offenders with the question: “Are they prepared?” The question may as well be directed to society as a whole: “Are we prepared as neighbors, co-workers, family members, and employers to make room for former inmates in our communities?” The needs of women transitioning from prison to the community are a pressing national issue and one that merits examination that can inform policy and practice taken as a response. We have some understanding of who goes to prison and the factors that relate to women’s criminal behavior and consequences, but we know far less about how women exit prison and manage the process of reentry (Vishen, 2005).

A massive number of offenders are released from prison from year to year. In the US alone, the figure is placed at 600,000 yearly (MDRC, 2007; Bierens & Carvalho, 2007). This is an offshoot of growing criminality in many parts of the world. In 2003, the US National Crime Victimization Survey placed the crimes committed that year at 24 million. Of these crimes, 18.6 million or 77 percent were property crimes, 5.3 million or 21 percent were crimes of violence, and.1 million or 1 percent were personal thefts (Perry, 2004). These offenses brought 1,470,045 people into federal and state prisons and 6.9 million into probation or parole. This means that 3.2 percent or 1 in every 32 American adults was in trouble with the law and will bear the social stigma of an ex-convict upon their release. Based on 2005-06 data on first admission to prison of offenders, 9 percent of all American males are incarcerated in state or local prisons at one point in their life (Bierens & Carvalho, 2007). The percentage of incarceration rises rapidly from the teenage years to age 40, and still increases thereafter but on a slower rate. The conclusion is that a big majority of men working in normal society have been incarcerated at some point in their lives, and an even larger proportion have been under supervision of the criminal justice system one way or another (Bonczar & Beck, 2000). Estimates are that between 600,000 and 700,000 inmates, or about one-third of the actual prison population, leave prison every year to reenter civil society (Freeman, 2003).

Deferred Adjudication

Deferred adjudication is a special form of judge-ordered resolution of a criminal case that evolved from the concept of probation. In regular probation, there is a finding of guilt and subsequent conviction for a crime, the sentence for which is suspended. In a DA case, no conviction or sentence is involved and the judge defers the finding of guilt for as long as the defendant successfully complies with the conditions of supervision. Offenses eligible for DA are mostly misdemeanors but also include sex offenses, drug use and felonies, which may be classified as either Class A, B and C. Drunken driving and similar misdemeanors are classified as Class A and B offenses and entail only two days of maximum supervision. Class C offenses require a DA supervision of up to 180 days in cases involving sex offenses and drug abuse, while felonies take as long as 10 years (Bradley, 2006).

When the DA system was first adopted in many states, the rule was that once the mandated period of supervision was completed, this will not reflect in the defendant’s record, especially in the case of first offenders. Over time, however, amendments to the DA law changed its complexion such that cases involving violent assaults as well as second offenses are to be reflected in the official records. Federal law also required that DA cases must be inputted in immigration proceedings. Thus, while DA beneficiaries are spared formal conviction and punishment, this does not mean that there are no negative consequences. Violation of the conditions of supervision also makes the defendant subject to punishment without further trial and he is deprived of the right to appeal if the judge handling the case says he is guilty. The admission of guilt, which is a prerequisite for DA coverage, may be used in deportation hearings or it could be enough to cancel the defendant’s chances for employment. In fact, DA is treated as though it is a conviction by schools, law enforcement agencies, banks, insurance companies and apartment lease owners.

Employment & Crime

The stream of research in the past 60 years has established the strong association between employment and crime. People who offend are more likely to be unemployed than their peers and are more likely to re-offend if they are unemployed (Andrews, 1995, pp.35-62; Farrington et al, 1986, pp.356). In UK, for example, a study of over 1,000 persons under supervised probation found that only 21 percent were in active employment compared to around 60 percent of the general population (Mair and May, 1997, pp.10-15). However, Sherman et al., (1997, pp.322-325) found this relationship complex, as does Uggen (2002, p. 529), who reports that while unemployment is associated with higher levels of crime in adult offender populations, employment has been found to be positively associated with crime in the case of juvenile offenders. Another expression of dismay at this complex relationship is that of Field (1999), who looked at the macro relationships between crime rates and the economy in the UK context. The finding was that when consumption was low and unemployment high, property crimes were also high but when consumption was high, violent crimes were also high. It would seem then that while it is generally true that employment and crime are negatively associated, this relationship does not occur across all ages or types of crime (Field, 1999, p. 675)..

Since unemployment is associated with offending, it is imperative to explore and evaluate programs that promote employment for offenders as a method of reducing crime and recidivism. It has been consistently shown that employment for offenders serves to reduce the likelihood of their offending (Farrington et al, 1986, p.350; Gendreau et al, 1998, pp.10-13). For such an intervention effort to work, however, there must be a causal relationship between employment and crime, which has been more difficult to establish. There are a number of plausible explanations for the association between employment and crime, such as:

- Lack of legitimate means of getting money may lead to crime.

- Unemployment may lead to boredom, which may in turn lead to involvement in drugs or fights.

- Employment may encourage social integration and therefore act as a protective factor.

- Being unemployed and offending may be associated with similar risk factors, such as problems with anger management, living in a poor community where unemployment and crime are high, having problems with drugs, etc.

- Having a criminal record may cause unemployment (Farrington, et al., 1986).

The literature points to four major dampeners to the employment prospects of offenders:

- Offenders tend to have lower levels of education, qualifications and vocational skills than other members of the community and this may act as a barrier to employment (Parsons, 2002, pp.19-25).

- Offenders may have psychological problems, including drug abuse, which make keeping a job difficult (Gendreau and Ross, 1980, pp.432-440).

- Living under such circumstances as insecure housing and in areas of high unemployment can act as a barrier both to gaining work and keeping it.

- Employers are reluctant to hire people with a criminal record

As a consequence of this complex picture, it is increasingly being recommended that interventions aimed at reducing re-offending should address as many potential barriers as possible (McGuire, 1995, p.90), though, as Bouffard et al (2000, pp.1-41) point out, this makes it difficult to determine what aspects of interventions are responsible for positive outcomes. The uncertainty of these inter-relationships also casts doubt on the role of employment programs in crime reduction, although offenders themselves consider that assistance in getting into employment is critical in helping them stop re-offending (Gillis et al, 1996, pp.3-5). It is to clarify these relationships that interventions are evaluated to determine ‘what works’. The review has systematically identified such studies for in-depth examinations and synthesizing

Upon the release of the ex-offenders estimated at between 600,000 and 700,000 yearly, they join millions more released from probation in non-supervised setting and at least 3 million other ex-convicts who have released from prison in the preceding year (Freeman, 2003). Such a heavy influx of ex-convicts into society raises serious concerns about its social and economic consequences (Bloom, 2006) because of the sad prospect of recidivism, which means unabated spending on prison maintenance, overcrowding jails and costly restitution of crime victims. To avoid these costs, there is a nearly unanimous belief that public authorities should spare no effort and resources in combating recidivism by working for the successful reentry of ex-convicts into society through employment (Freeman, 2003).

Research consistently shows that former prisoners who found employment are less likely to return to jail (State Progress, 2007), since employment helps them establish law-abiding lives. This supports the theory that employment for offenders benefits society by reducing the incidence of offender recidivism. The big problem is that many factors conspire to erect a barrier between ex-convicts and the world of work, among them the stigma of prison, the inherent lack of education and skills, the reluctance of employers to trust people with an unsavory record, lack of community effort to accommodate returnees, and distorted values of some offenders that make them naturally susceptible to recidivism (Langan & Levin, 2002; Saylor & Gaes, 1997).

In Michigan, the world saw the first comprehensive effort to test intervention measures aimed at toppling the barriers to employment confronted by offenders as well as other low-income sectors of the population that subsist on welfare (MDRC, 2007). The name given to the program, Enhanced Services for the Hard-to-Employ, was appropriate enough as it seeks to find and promote ways to boost employment, promote well being and reduce welfare receipt for the target beneficiaries. There were other state projects recruited for the endeavor but this paper focuses its attention on a program appropriately called Center for Employment Opportunities in New York City, as well as the Transitional Work Corp. in Philadelphia, Early Head Start in Kansas and Missouri, and Mental Health Evaluation in Rhode Island. All these intervention programs for ex-offenders sought to place released prisoners in transitional state-supported employment for 2-3 months, followed by job placement in unsubsidized jobs. The services consisted of a fatherhood program, employer-driven skills training, job coaching and post-placement retention services. As for the evaluation process, the components included:

- Implementation and process analysis – this examines how the programs operate based on site visits and interviews with program staff and administrators.

- Impact analysis – this employs a rigorous research design to measure the program’s effects on outcomes, including employment, welfare use and family functioning.

- Cost analysis – this compares the financial costs and benefits of the intervention programs from the perspective of both participants and government budgets. (MDRC, 2007)

In 2004, half of the prospective participants in New York were randomly assigned to a program group, which became eligible for the special services provided by the Center for Employment Opportunities. The other half was randomly assigned as well to a control group, which was eligible only for standard services. The outcomes for both groups would be followed up for three years, after which the final results will be known, but the early feedbacks were as encouraging as the modest success posted by ESEO. Like the ESEO in Bierens & Carvalho (2007), the Enhanced Services for the Hard-to-Employ also set the criteria for participation as: 1) voluntary acceptance of the program services, 2) incarceration at an adult federal, state or local correctional facility for at least 6 months, 3) release from prison within 6 months of participation, and 4) a pattern of income-producing offenses.

Recidivism

Recidivism is defined according to the number of re-arrest, conviction and incarceration (Gendreau, et al., 1996), with re-arrest emerging as the most reliable among the three possible measures (Beck & Shipley, 1989). To address overcrowding in prison and probation settings, which is a common phenomenon in both developed and developing countries, research prevails upon authorities to develop the ability to predict offender recidivism accurately. The likely candidates for recidivism are the younger offenders who have unstable employment, given to alcohol and drug abuse, exhibit pro-criminal attitudes and associate with criminals (Hanson & Bussiere, 1998). According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders of the American Psychiatric Association, the characteristics of potential recidivists include a “criminal lifestyle,” an anti-social personality, “psychopathy (Hare, et al., 1990)” and “lack of self-control (Hanson & Bussiere, 1998).” Criminologists measure the severity of recidivism based on either count or duration data. The count method measures recidivism based on the number of arrests and date of release, while the duration method is based on the time difference between a prisoner’s release and his first re-arrest (Bierens & Carvalho, 2007). The latter type of measurement complicates the model but this is widely considered to be the right way because it confirms the notion that recidivism is the time interval following the occurrence of a first event (Bierens & Carvalho, 2007).

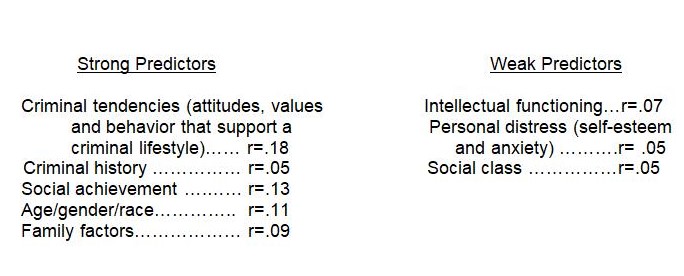

The most common measures of recidivism, as noted above, are reconviction, re-arrests, together with self-reports and parole violations. Hanson & Bussiere (1998) studied 87 relevant papers on criminology trends in Australia, Denmark, Norway, UK and the US and gave reconviction the highest rating of 84 percent as measure of recidivism, followed by re-arrest at 54 percent, self-adimission of offenders at 25 percent and parole violations, 16 percent. Gendreau, et al. (1996) also evaluated 131 studies published since 1970 and identified the effective predictors of recidivism and other commonly used but weaker predictors. The best predictors include anti-social attitudes and values, anti-social personality, bad companions, substance abuse and a family with a history of criminality. Other influencing factors are demographic variables like age, sex and civil status, in the sense that a huge proportion of recidivists are usually young, male and unmarried. The weaker predictors of offender recidivism are identified as the poor quality of a person’s intellectual functioning, his level of distress and the social class he belongs to. In the Gendreau, et al. (1996) review, the correlation “r” was set as a statistical measure of the strength of association between two variables of a perceived predictor of recidivism. As shown in the figure below, the predictor variable that was valued at.20 is to be considered important.

There is a popular assumption that the forced isolation and dispossession of incarceration should serve as learning experience for convicts to mend their ways, but all the existing data on recidivism show that a prison term hardly reforms offenders (Freeman, 2003). For most men aged 20-40, prison has a revolving door – they commit a crime, get arrested and imprisoned, spend some time in prison, get out, commit another crime, get arrested, incarcerated, ad infinitum (Langan & Levin, 2002). About two-thirds of all released prisoners are rearrested and one-half re-incarcerated within three years of their release from prison. After this 3-year period, the rate of recidivism rises even faster that 75-80 percent of released prisoners are likely to be rearrested within a decade of their release (Langan & Levin, 2002). The high rate of recidivism notwithstanding, it does not mean that imprisonment has no effect at all on the criminal behavior of prisoners. The National Recidivism Study of Released Prisoners conducted by the Bureau of Justice Statistics in the US indicates that the rate of criminal activity is lower after incarceration than before. In 1994, 93 percent of released prisoners surveyed were re-arrested but only 67 percent of the same prisoners were arrested within 3 years after their release. This slower increase in the rate of arrests suggests that arrests after release are at least 10 percent lower than the 93 percent arrests before incarceration (Freeman, 1999). BSJ arrest records in 1994 also showed that the released prisoners averaged 2.7 arrests in 3 years after release, which amount to 0.9 arrests per year. For the same prisoners, the average number of arrests prior to incarceration is 15. The conclusion is that incarceration somehow reduces the rate of arrest, thus lessening the amount of crimes committed by these persons. However, the high rate of recidivism remains for the greater number of offenders that exhibit the characteristics described in Beck & Shipley, 1989; Freeman, 2003; Gendreau, et al., 1996). The initial challenge of rehabilitation is to overcome this recidivist tendency of offenders by putting up job-search programs based on their behavior during their 2 to 3 years stay in prison and the additional years served by violent offenders on their sentence (Freeman, 2003).

Low Labor Market Value

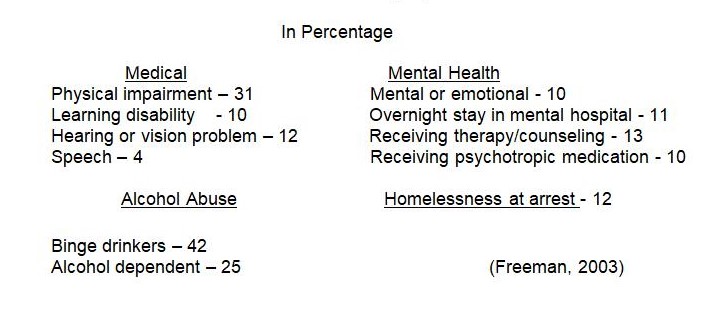

A job is a means for survival for anyone and serves to improve one’s self-esteem, increases his attachment to the community and develops his sense of belonging to a group (Bierens & Carvalho, 2007). It is well established in criminology literature that having a job diminishes the chances for recidivism (Harer, 1994). If ex-convicts can establish law-abiding and productive lives upon their release, they are less likely to fall back into crime (State Progress, 2007). The problem is a wide range of obstacles prevents ex-offenders from finding a job (MDRC, 2007). It starts with the values, preferences and personality traits, including physical handicaps that set offenders apart and make them unsuitable for employment. The magnitude of this particular problem is illustrated in table below, which is based on 1997 data.

As observed in the table above, such physical and mental conditions as hearing, vision and speech difficulties can by themselves reduce people’s value in the labor market and thus make them prone to crime. Offenders’ employability is discouraged by any mental problem, alcohol and drug abuse, including homelessness that usually engenders anti-social behaviors. As if these built-in drawbacks are not enough, administrative surveys show that incarceration inherently reduces people’s employment and earning prospects (Freeman, 1999). This reinforces the theory of Bloom (2006) that incarceration is not the only reason for the low job market performance of ex-offenders, but also the characteristics that caused the commission of crime and the subsequent conviction.

Holzer, et al. (2001) conducted a multi-city survey involving four major cities in the US and asked employers at random if they would hire applicants with a criminal record. Of the employers interviewed, 12.5 percent said they would, while 25.9 percent said they probably would. This meant that 38.4 percent went flat-out against accepting ex-convicts. Among the reasons cited by those who expressed reluctance in hiring ex-offenders were lower education, less work experience and physical and mental issues. Lack of education and employable skills is a common factor among people who dabble in crime. A Bureau of Justice Statistics survey reveals that 19 percent of released prisoners have less than 8 years of primary education, and a heftier 67 percent have less than secondary schooling (Freeman, 2003). Their employment prospects upon release from prison are further dimmed by the competition posed by the influx of similarly unskilled immigrants and the increasing labor market trend that puts a premium on more educated workers (Freeman, 2003). On the off chance that offenders find employment upon release, they perform unsatisfactorily and earn less than other workers with the same demographic descriptions (Freeman, 1999). Studies show that only 39 percent of parolees succeed in turning a new leaf and 42 percent of those discharged from parole are returned to such supervised arrangement for breaking their parole terms. Still and all, there is a general agreement among the social, economic and criminology circles that a public policy that assists ex-offenders in finding a job soon after their release will go a long way in decreasing the incidence of recidivism (Bierens & Carvalho, 2007).

Reentry Strategies

The major criticism against the existing rehabilitation programs for ex-offenders is the lack of sufficient funding allocations, follow-up strategies and the absence of thorough reentry planning. As a result, the communities where the ex-offenders need to reenter often lack the capacity to meet the requirements of the returnees in terms of treatment, housing, employment services and family reintegration (Perry, 2004). In the 1970s and 1980s, the US government sponsored a series of evaluations of in-prison job training and post-release employment intervention programs to see how these help in the complete rehabilitation of offenders. The results of the initial study of one program that emphasized financial assistance and job placement services were mixed, so attention was turned to programs with a community-based approach (Bloom, 2006), but there were few of such reentry models that are at the same time rigorous and fully dedicated to employment (Bierens & Carvalho, 2007). A little later in 1980-85, the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) sponsored a controlled experiment to evaluate the impact of reemployment programs for recently released prisoners. This involved three well-established programs: the Comprehensive Offender Employment Resource System in Boston, Project JOVE in San Diego and Safer Foundation in Chicago.

The Safer Foundation, like its counterpart programs in Boston and San Diego, provides training on job preparedness, placement and retention, youth and adult education, and support services. Its work begins upon prison entry with an individualized reentry planning. Even while in prison, the offender receives job training and career development lessons. Upon the prisoner’s release, he is given assistance on job placement, retention and career advancement, as well as integrated services through cooperating organizations like Gateway, TASC, vocational and educational providers, and correctional authorities The overall objective of this effort is to see that the offender enjoys a living wage, lives in safe and affordable housing, remains drug-free and has stable social support in terms of strong family and community involvement (Perry, 2004). Joyce Foundation in Michigan places the same emphasis on follow-up services through its own employment-based reentry program called “Transitional Jobs Reentry Demonstration.” Under the TJRD program, convicts are assisted in finding wage-paying jobs soon after their release from prison. Once the offenders are placed in a temporary job, the TRJD staff identifies and resolves any workplace behavior that may cause problems in their transition to a permanent job. After a few months in this transitional job, the staff assists offenders in looking for a permanent position and given additional post-placement support. The MDRC follow-up is good for at least 1 year (MDRC, 2007). To test the effectiveness of the initial implementation of the program, the MDRC is also conducting an experiment using the control and treatment group method, with both groups receiving the basic job search services but the treatment group afforded special follow-up services. Evaluation of the experiment will be completed in 2009.

In the NIJ experiment cited earlier, a total of 2,045 prisoners were randomly assigned to either a treatment group or a control group. The treatment group received the normal services consisting of orientation, job search coaching and seminars and assistance, plus special services provided by a specialist who guides and assists participants during the job search and for 180 days after job placement (Milkman, 2001). As for the control group, only the normal services were made available. Initial results of the experiment showed that the effects of special services were negligible, although there was a noticeable treatment effect on recidivism. However, the magnitude and direction of this treatment effect were dependent on location and age of the offenders (Bierens & Carvalho, 2007). In Chicago and San Diego, the risk of recidivism in the control group was reduced for ex-inmates over age 27 and above age 36 for those in Boston. Nonetheless, the attrition rate and job search duration for the control group in San Diego and Chicago were significantly higher than those in Boston (Heckman, et al., 1999), indicating that the standard services given to ex-inmates in the latter state may be more effective than those in Chicago and San Diego. The motivation for participation is thus higher in Boston. For all ex-offenders in the treatment group, the risk uniformly increased. Heckman, et al. (1999) believe that some programs of this nature work well for others and may fail for a given group because of the different characteristics of the offenders who usually make use of these services.

The COERS program, Project JOVE and Safer Foundation were found to have achieved some success in addressing the problem of offender recidivism and employment in their respective states because of a project design that makes follow-up strategies an important part of the program. This success gave the Department of Justice the idea to replicate the programs on a nationwide level, through the Employment Services for Ex-Offenders Program (ESEO). Based on the experience of COERS, JOVE and Safer Foundation, the ESEO program was so designed that it was implemented in three phases. In the initial phase, the ex-convict is offered assistance in the form of food provision, transportation, clothing and the like. For the next phase, the offender is prepared for the job search by teaching him how to dress and behave property in front of the prospective employer, how to conduct himself during a job interview. The offender is also given lectures on responsibility and workplace values. Assistance for the actual job search is reserved for the final phase, which comes with the guarantee of follow-up services such as crisis intervention, counseling and re-employment assistance when necessary. The follow-up services are available for 6 months after the initial job placement (Bierens & Carvalho, 2007).

On the follow-up services, Perry (2004) and Saylor & Gaes (1992) suggest that changes in offender behavior must be measured routinely and it does not matter which type of outcome measure for recidivism is used. The policymakers’ knowledge and benefit practices will be enhanced if the correctional agencies compare the ability of different actual measures to predict recidivism; assess the usefulness of new actuarial techniques; and generate prediction data on promising predictor domains and distinct groups of offenders such as sex offenders (Gendreau, et al., 1996).

Findings & Evaluation

The rehabilitation programs taken up for this study work for the most part but the effort needs improvement because the outcomes are primarily addressed at recidivism and less on labor market success (Saylor & Gaes, 1997). Some of these rehabilitation programs endeavor to impart “socially acceptable values” to prisoners through in-prison ministries, moral teaching and a meeting between offender and victim, which is praiseworthy as it were. However, nothing in the literature indicates that authorities deal adequately with the often ill-conceived values and preferences and medical problems of inmates, which serve as dividing wall between them and the world of work. With 19 percent of prisoners released in a given year having less than 8 years of schooling and 67 percent with less than high school, their job market value is nil.

This educational handicap is given a relatively high measure of 1.741 as predictor of recidivism together with age, which rated 2.098 (Maltz, 1984). Apart from education and age, the other influencing factors that keep coming up in the literature are sex, race and drug use. Freeman (2003), for example, notes that males make up 94 percent of the population in state prisons, 88 percent of those in local jails, 78 percent of those on probation and 88 percent of parolees. In the same study, black inmates comprise 47 percent of the prison population, 41 percent of those in jails, 31 percent of those on probation and 41 percent of parolees. As for drug and alcohol abuse, 42 percent of all inmates in 1997 were found to be binge drinkers while 25 percent were binge drinkers (Freeman, 1999).

An offender’s decision to turn his back on crime and integrate into the job market has been shown to be dependent on the incentives that come his way and the preferences or values with which he assesses those incentives (Saylor & Gaes, 1997). Analysts look kindly to such incentives, believing that they could raise the risks of re-arrest and re-incarceration for offenders. If the reentry programs provide reasonable reward from legitimate work, this would make re-incarceration unattractive to offenders (Freeman, 2003).

The ESEO experiments showed that employment programs for ex-offenders will reduce recidivism rates as long as these take into account the heterogeneity of the participants, such that the corresponding services are provided on a case-to-case basis. A program that extends the same kind of services for everyone may not yield the expected results (Bierens & Carvalho, 2007). Given the different characteristics of the individuals who make use of these services, some programs may work well for others but may fall short of expectations for a given group (Heckman, et al., 1999). This was demonstrated in the ESEO evaluations of the JOVE and Safer Foundation programs in San Diego and Chicago, respectively, whose attrition rate and job search duration were found to be significantly higher than those of COERS in Boston. The possible reason is that the standardized services in Boston are more effective for the kind of ex-inmates that COERS deals with that makes motivation for participation higher.

Wheeler & Hissong (1987, pp.510-527) compared the recidivism rates of misdemeanor offenders (Class A or B misdemeanor convictions, excluding driving while intoxicated) who received fines, probation, or jail sentences in Houston, Texas. Recidivism was defined as any Class A or B misdemeanor or felony violation. With three years of follow-up, which considered the offenders’ criminal history and demographic factors, the researchers found that probation was superior to fines and jail sentences in terms of reducing recidivism. Although the results were not conclusive due to potentially uncontrolled factors which may have influenced prosecution as well as the offenders’ self-selection, the researchers explained that perhaps post-disposition supervision procedures imposed by probation were better deterrents to subsequent new offenses than a relatively brief jail experience.

Gottfredson et al. (1973, pp.360-362) studied 104,182 male prisoners in 14 offense categories in the United States who were paroled for the first time between 1965 and 1970. The follow-up time was one year, with recidivism defined as a return to prison. The median time served by the offenders before the grant of parole ranged from 12.2 months for fraud offenders (non-check fraud) to 58.6 months for homicide offenders. In this study, attempts were made to statistically control for the effects of offense type, prior offense, and age. The results of the study indicated that while on parole, offenders with the longest time served generally had higher recidivism rates than offenders with the shortest time served. The significance of the association between time served and the recidivism rates varied across different offense categories. For property offenders, all subgroups (auto theft, check offense, burglary, larceny, and fraud) that served the longest time had higher recidivism rates than those subgroups that served the shortest time. For armed robbery and drug offenses, however, offenders with longer sentences had slightly lower recidivism rates than offenders with shorter sentences.

Beck & Hoffman (1976, pp.127-132) followed the progress of 1,546 adult federal prisoners in the United States for two years after their release. The offenders were categorized according to their “salient factor score” which took into account their prior criminal history, age, education, employment history, and marital status. The offenders were first grouped according to their scores, and were further divided according to the time served. Results showed that there was no substantial association between time served and the recidivism rates. Orsagh & Chen (1988, pp.155-171) tested the theory that there is an optimum sentence length that effectively minimizes recidivism rates. This research focused on 1,425 offenders released from a North Carolina prison in 1980, of whom 40 percent had been incarcerated for robbery or burglary. These offenders were followed up for two years based on the definition of recidivism as a post-release arrest. After controlling for the potential effects of age, race, marital status, employment, and criminal history, the findings indicated that:

- For robbery offenders, the probability of re-offense increased with the amount of time served.

- For burglary offenders, the estimated optimum time served was 1.3 years for younger offenders (younger than the median age) and 1.8 years for older offenders.

In effect, the study showed that beyond 1.3 years, recidivism rates increase for younger offenders. Sims & O’Connell (1985, p.65) studied the impact of early release programs through the behavior of 1,674 prisoners in Washington who received early parole between 1979 and 1984 in six early release efforts. On average, these offenders were released 4.6 months earlier than expected. A group of 1,867 offenders who were released 12 months before the first early release effort was used as a comparison group. The study, which proceeded on the concept that recidivism is the event when an offender returns to prison, showed that, in general, the recidivism rates of the early release offenders at one, two, and three years of follow up were lower or about equal to the recidivism rates for the comparison group.

On the types of offenses, the new offenses committed by the early release offenders were similar to those committed by the comparison group, but offenders convicted for their third offense were shown to have higher recidivism rates than the comparison groups. The research thus suggests that the higher recidivism rates in the third early release effort were most likely due to a higher percentage of habitual offenders. In this study, the independent effect of early release on offender recidivism was not assessed. Austin (1986, pp.404-502) evaluated the recidivism rates in a sample of 1,428 prisoners who received early release from Illinois prisons between 1980 and 1983. This sample represented a total of 21,000 early-release prisoners, whose recidivism rates were compared with those of offenders who served their full term during the same period. On average, these offenders were released 3.5 months earlier than their full sentence.

After one year of follow-up activities, the research showed that the re-arrest rate for those who received early release was 42 percent, which was lower than the 49 percent rate for the offenders who served their full prison term. After controlling for the effect of age, criminal history, severity of current offense, and institutional conduct, however, the lower recidivism rate was not attributed to early release. The author concluded that early release had no impact on overall recidivism rates.

Summary & Conclusion

After decades of attacking the problem of recidivism, the evidence shows that it remains unabated based on overcrowding at prisons, of which a huge percentage of inmates are recidivists or prisoners who are serving repeat sentences. The characteristics of recidivists are unchanging and these include young age, unstable employment, alcohol and drug use, pro-criminal attitudes and a tendency to associate with criminals and lawbreakers. Moreover, they are predominantly male, with homelessness, poor schooling and mental and physical deficiencies in their background. Studies suggest that employment can reverse the trend of recidivism, but the above-cited traits make convicts patently unsuitable for employment upon their release from prison. This is exacerbated by the fact that a criminal record discourages employers from accepting an ex-convict because of the social stigma attached to it. There is also the prevailing condition in the workplace in which the diminishing number of jobs could not accommodate the yearly increase of the workforce entrants.

All these difficulties in seeking employment for ex-offenders are duly recognized by authorities such that there is now a long list of employment services designed for offenders. Any program that seeks to reduce recidivism is necessary and socially beneficial because of the high cost of crime and incarceration. There is a thin line that divides crime and employment, which is also very diffused for many people released from prison (Freeman, 2003). Getting a job for an ex-offender does not always mean that he will eschew a criminal opportunity if it arises. Finding a job may delay recidivism but it is not likely to eliminate the problem. From the evidence, employment assistance for offenders that follows up the service until the participant settles down works for such programs as COERS in Boston, Project JOVE in San Diego, Safer Foundation in Chicago, Transitional Jobs Reentry Demonstration in Michigan and the Department of Justice-sponsored ESEO. However, even the administrators of these programs acknowledge that there is so much work that still needs to be done.

To conclude, only a limited number of studies have examined the relationship between time served and post-release recidivism. For some offenders, incarceration and longer confinement increase the risk of recidivism. For other offenders, recidivism rates will either be unaffected or reduced by longer terms of incarceration. It is possible that for some types of offenders, there is an optimum length of sentence that can have the effect of minimizing recidivism. Early release appears to neither increase nor decrease the overall recidivism rates. More research is needed for a better understanding about the effects of time served and early release on the re-offending behavior of specific types of offenders.

Some offenders were also shown to be at greater risk of re-offending than others because of the different influence on individuals of such factors as gender, race, age, and the number of prior offenses. The risk of recidivism is also determined by a number of other factors such as education, employment, housing stability, links with family, physical and mental health, and drug and alcohol issues. There are a number of risks associated with determining a proper response to recidivism – the risk of future harm to potential victims should the offender re-offend, as well as the risk of overestimating the likelihood that an offender will re-offend and thus unnecessarily impinging on his or her rights. The correct balance between these competing risks can be difficult to determine and it is a desire for this balance that lies at the core of the debates on recidivism. The issue of how best to respond to re-offending is likely to continue into the future as key stakeholders persist in seeking new ways of effectively reducing the risk of recidivism.

Correctional work in a prison setting promotes the concept of rehabilitation that involves efforts to promote a work ethic, time keeping, and other job-related skills among convicts. This type of intervention is sometimes criticized for using outmoded equipment and tools that are not relevant outside the prison context. Community employment programs are often used to relieve prison overcrowding as its primary goal rather than to promote desirable outcomes for individual inmates. As a result, the quality of program often suffers. However, it is considered good strategy to include a wide range of interventions ranging from halfway houses and tagging to community job schemes and preparations for work while the offenders are in custody, to be followed by career guidance and employment services after release.

This paper gained valuable insights from the studies discussed in the literature review, such as that some offenders released to the community refuse to attend programs or drop out fairly quickly, thus making employment assistance programs for them doomed from the start. This suggests that in the community, it must be a primary objective for public policy and program administrators to understand what will motivate participants and tailor programs to reflect their needs. However, community programs reported in the literature tend to focus on older, hard-core offenders at the expense of younger offenders and youth at risk. Such programs need to give more attention to this group, which emerges from the literature on recidivism as the most difficult to help, such that the apparent ineffectiveness of community employment programs may be an artifact of the age of the participants. Before writing off the employment interventions for the young, however, we should consider Lipsey’s (1995, p.20) meta-analysis of 400 studies exploring the effectiveness of treatments on young offenders. The most effective programs, according to that study, that operate within the juvenile justice system involving the probation, prison or parole systems are those targeting employment as end goal. This may not be true for the programs run by voluntary and non-government organizations, though the reason for this was not clear. Just the same, although younger offenders may be more difficult to engage, it does not appear to be a viable option to focus employment programs only on older age groups.

Employers everywhere are not eager to offer jobs to people with a criminal record and trying to change this mindset may be difficult. But this study shows that with the right strategy, such as helping offenders find employment soon after their release, will help ease the problem of recidivism. For the community reentry programs to succeed, it is important that more and better data are made available as input for their design. This may include minute details about the organizations that have helped inmates find a job as part of their caseloads. More detailed information is also needed about the offenders themselves – their criminal and employment history, status of release, time served compared to sentence duration, family characteristics, level of participation in the job search, and past and present evaluations of employers. Moreover, greater attention should be given to the attrition problem involving offenders who drop out of a program. This is not unusual for offenders, given the anti-social attitudes that many of them exhibit, but their reasons for dropping out must be traced and assessed carefully to determine the best ways to address the problem.

References

- Andrews, D. (1995). “The Psychology of Criminal Conduct and Effective Treatment.” In Reducing Re-Offending: What Works, J McGuire (ed), John Wiley & Sons, 35-62.

- Austin, J. (1986). “Using Early Release to Relieve Prison Crowding: A Dilemma for Public Policy.” Crime and Delinquency 32 (4), 404-502.

- Beck, J.L. & Hoffman, P. (1976). “Time Served and Release Performance: A Research Note.” Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 13, 127-132.

- Beck, A. & Shipley, B. (1989). “Recidivism of Prisoners Released in 1983.” Special Report, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 81-89.

- Bierens, H. & Carvalho, J. (2007). “Job Search, Conditional Treatment and Recidivism: The Employment Services for Ex-Offenders Program Reconsidered.” Department of Economics, Pennsylvania State University, 971-993.

- Bloom, D. (2006). “Employment-Based Programs for Ex-Prisoners: What have we Learned, What are we Learning, and Where should we go from Here?” Michigan Disability Rights Coalition.

- Bonczar, T. (1997). “Characteristics of Adults on Probation, 1995.” NCJ 164267.

- Bradley, J. (2006). “Deferred Adjudication.” Texas Bar Journal 296.

- Farrington, D., Gallagher, B., Morley, L., St. Ledger, R. & West, D. (1986). “Unemployment, School Leaving and Crime.” British Journal of Criminology, Vol. 26, 335-356.

- Freeman, R. (2003). “Recidivism vs Employment of Ex-Offenders in the US: Can We Close the Revolving Door?” New York University Law School.

- Gendreau, P. Coggin, C. & Gray, G. (1998). “Case Needs Domain Employment.” In Forum on Corrections Reseach , Vol. 10, 3-13.

- Gillis, C., Robinson, D. & Porporino, F. (1996). “Inmate Employment – The Increasingly Influential Role of Generic Work Skills.” Forum on Corrections Research, Correctional Service of Canada, Vol. 8 (1), p. 4.

- Hanson, R. & Bussiere, M. (1998). “Predicting Relapse: A Meta-Analysis of Sexual Offender Recidivism Studies.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, Vol. 66, No. 2.

- Holzer, H., Raphael, S. & Stoll, M. (2001). “Will Employers Hire Ex-Offenders? Employer Preferences, Background Checks and their Determinants.”

- Langan, P. & Levin, D. (2002). “Recidivism of Prisoners Released in 1994.” NCJ 193427.

- Lipsey, M. (1995). “What do we Learn from 400 Research Studies on the Effectiveness pf Treatment with Juvenile Delinquents?” In Reducing Offending:What Works – Guidelines from Research and Practice, J McGuire (ed), Chichester: Wiley, p. 20.

- Maltz, M. (1984). “Recidivism: Quantitative Studies in Social Sciences.” Academic Press, Orlando, FL.

- MDRC (2007). “Transitional Jobs Reentry Demonstration.” Web.

- Orsagh, T. & Chen, J.R. (1988). “The Effects of Time Served on Recidivism: An Interdisciplinary Theory.” Journal of Quantitative Criminology 4 (2), 155-171.

- Saylor, W. & Gaes, G. (1992). “REP Study links UNICOR Work Experience with Successful Post-Release Outcome.” US Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Prisons.

- Sims, B. & O’Connell, J. (1985). “Early Release: Prison Overcrowding and Public Safety Implications.” Office of Financial Management, Olympia, Washington, p. 65.

- State Progress (2007). “Improving Public Safety by Removing Barriers to Employment for People with Criminal and Arrest Records.”

- Uggen, C. (2000). “Work as a Turning Point in the Life Course of Criminals: A Duration Model of Age, Employment and Recidivism.” American Sociological Review, Vol. 65 (4), p. 529.

- Vishen, C. (2005). “Ex-Offender Employment Programs and Recidivism: A Meta- Analysis.” Urban Studies Institute, Washington, p.33.