Executive Summary

Media companies use strategic alliances as one of the main tactics to compete on the global media market. Need to collaborate caused by changes occurring in the social, economic, and political environments. Strategic alliances allow media companies like AOL to meet new economic and legal challenges.

In the paper, it is discussed that strategic alliances allow media companies to create sustainable competitive advantage and deliver quality products to the end audience. The examples of such giants as AOL – Google, Allied Media and Mercantile Advertising show that the attractiveness of strategic alliances activity is the assumption that an alliances will enhance the growth potential of the acquiring company. Using concepts and methods from strategic management and marketing, current state and structure of the media industry is analyzed.

Table of Contents

Table of Figures and Appendices

Introduction

Media companies grow annually and require new ways and strategies to compete on the global scale. Many media businesses integrate themselves into the world economy through strategic alliances. Far-reaching changes are occurring in the social, economic, and political environments, affecting the strategies, structure, and management of media business. “The media sector encompasses the creation, modification, transfer and distribution of media content for the purpose of mass consumption” (A definition of the media sector 2008). The notion of strategic alliances incorporates the need for considering the current economic context affecting the firm (Reed & LaJoux 1998).

A media firm will form an alliance with another firm in order to bring together specific skills and resources in such ways that may complement each other, without the complications and expenses associated with a merger. “Strategic Alliances are agreements between firms in which each commits resources to achieve a common set of objectives” (Rigby 2007). The immediate benefits of alliances are technological know-how, possibility to penetrate new markets, and to gain market share at the expense of well established industry leaders (Reed & LaJoux 1998). “An alliance is strategic when it is the means by which a firm seeks to implement, in part or in whole, elements of management’s strategic intent” (Rigby 2007).

The paper will focus on the reasons why media companies collaborate in the media sector, and discuss a strategic importance of strategic alliances in media sector. Also, a special attention will be given to strategic collaborations as a deliver of sustainable competitive advantage.

Strategic Alliances, Mergers and Acquisitions

Before identifying the reason why media companies are building strategic alliances the term alliance should be defined. Strategic alliance is a relationship between two or more companies providing opportunities for mutual benefit and results beyond what any single organisation could realise alone (Austin, 2000). “Companies may form Strategic Alliances with a wide variety of players: customers, suppliers, competitors, universities or divisions of government. Through Strategic Alliances, companies can improve competitive positioning, gain entry to new markets, supplement critical skills and share the risk or cost of major development projects” (Rigby 2007).

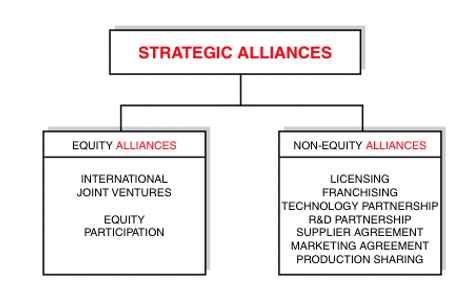

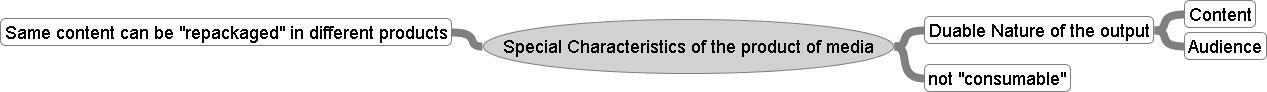

Culpan has identified nine forms of strategic alliances. These forms can be categorized depending on the equity involvement of the partnership in equity and non-equity alliances Figure 1.

Merger’s and acquisitions are like alliances forms of interorganizational relations. Namely they are both hierarchical relations. In a merger or an acquisition one company overtakes full control of another (Todeva and Knocke, 2005). This as also what it differentiates it from a strategic alliance, where according to (Yoshino and Rangan, 1995, p. 5) the two partners remain legally independent after the alliance is contracted.

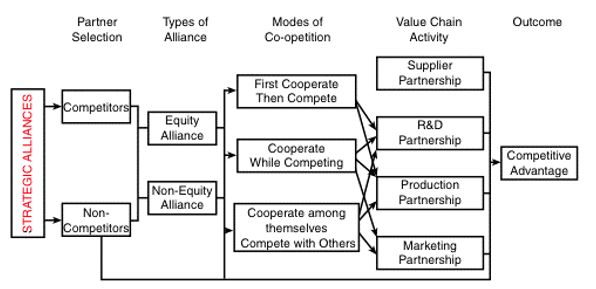

Depending on the relationship between the partners building the alliances a further classification of the alliance can be made, such as alliance among competitors or among non-competitors partner’s (Culpan, 2002). While (Webster, 1999) names many reasons why firms undertake strategic alliances, such as to reduce uncertainties in their internal and external environment, or gain a competitive advantage, (Culpan, 2002) in his framework (Figure 2) indicates the latter as the highest goal for a strategic alliance.

An alliance, in effect, brings together distinct and separate corporate entities. Each media company enters into the alliance complete with its own corporate culture, implicit or explicit behavioral systems, and management strategies. Each media corporation lacks an intimate knowledge of the operations of its partners. For the most part, upper management initiates, negotiates, and approves of the nature of the alliance, and once the arrangement is underway, the day-to-day management is left to other managers. This holds true for each member of the alliance; the best attributes of each firm must be harnessed for the benefit of the whole.

The dynamic management structure required by alliances includes the flexibility to take calculated risks. “In extending the IO model to strategic alliances, Porter and Fuller viewed strategic alliances as “coalitions” in the context of a firm’s international strategy” (Culpan 2002, p. 21). This translates into encouraging managers to develop their own initiatives and giving them the authority to implement decisions that are superior in their judgment. Under new leadership, the integration of the global resources of the media companies, their management, financial operations, administrative staffs, sales forces, customer tariffs, and tracking systems, is achieved in record time (Schiller, 1999).

The Macro-Environment of the Media sector

PESTEL

PESTEL analysis is a very useful tool to determine and analyze the influence of macro factors on the industry at first and as a consequence on a company’s position and competitiveness. Some concerns center broadly on competition, monopolistic practices, and market structure (Johnson & Scholes, 2002). The interest in macro economic issues is another indication of the field’s far-reaching status and importance in contemporary business world. The macro environment affects not only an organization in an industry, but also the whole industry itself. PESTEL analysis helps to determine the main factors of the market changes from the standpoint of a proposition and competition.

Political/legal

Strong legislation and stable economic situation in America and Europe allows media companies to sustain competitive market position. In spite of the fact that European Commission has the main influence on media industry, new rules accepted by EU Commission do not prevent media companies form rapid growth.

Socio-demography

Consumers worldwide are familiar with international brands and additionally are using locally produced goods that include materials or components supplied from abroad.

Environmental

Perspective, the end of 1990s was marked by the changes on the European market which altered many of the parameters of competition and thus enforced a period of reassessment and adaptation.

Technology

Is the main driven force in global economy (Picard, 2002). Advances in Information Technology and communication process have resulted in the availability of new channels of communication, an increased flow of information, and sharply lowered costs. While innovations in high technology often receive the greatest publicity, advances have been made in many fields and at many levels of Information Technology.

Economic

Environment in America and Europe is very favorable creating enormous opportunities to increase sales and profitability. National and regional economic health and growth have become increasingly dependent upon export sales as an engine of growth and as a source of the foreign exchange necessary for the import of the goods and services.

The Environmental and Industry Factors of the Media Sector

Following Picard (1990) media industry is complex and requires expertise and endless hours and billions of dollars to plan, develop, and place messages. The main global players in the industry are Disney, Time Warner, Viacom, News Corp, Sony, National Amusements, Lagardere groups, Allied Media and Mercantile Advertising, Axel Springer AG. Small media firms could not compete against larger, more established firms and are driven out or bought out by larger companies. Limited in budget and personnel, they are not able to respond to market changes fast enough and are unable to provide the necessary product, support, development resources, and marketing muscle to remain.

Today, the media industry is characterized by alliances and joint ventures that enable firms to keep pace with technological advances. These firms agreed to use each other’s capabilities and compete for international projects where each corporation’s specialization could provide very advantageous bidding. The extensive experience of large companies in managing major infrastructure projects overseas complemented objectives of marketing its telecommunications know-how in other nations (Demers, 1999).

The attractiveness or the presumed merits of strategic alliances activity is the assumption that a given strategic alliance will enhance the growth potential of the acquiring company (Schiller, 1999). Following Williams (2002) a media firm with a lackluster product line or with underperforming business units might seek to acquire one that would enhance its portfolio and provide improved growth potential.

Preferably, the goal is to acquire a complementary business unit with related lines of markets and products that would fit nicely into the firm’s long-term strategic direction, improving the acquiring firm’s overall growth potential and marketability. The selection of which company would fit best in the current corporate culture is based on many factors, and it varies from firm to firm.

In fact, even firms competing within the same industry segment might have very different acquisition strategies (Scherer & Ross 1990). A need to cooperate and create strategic alliances are explained by market changes and globalization processes. Following Alexander et al (1998): ‘the “Triad”, the United States, the European Union and the Pacific Rim nations (especially Japan)–are looking to new markets for their products and services, such as China and post-Communist central and eastern Europe” (p. 223). These changes affected media market and open new opportunities for global expansion.

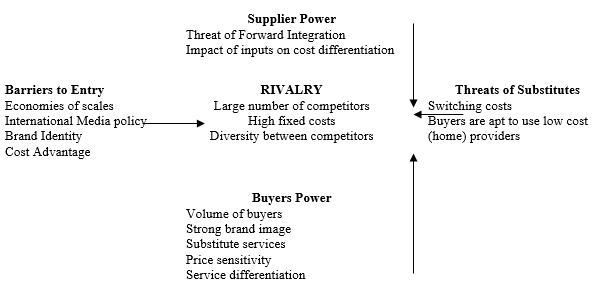

Porter’s Five Forces

In media sector, collaborations and strategic alliances allow companies effectively compete in today’s turbulent business environment. To be successful given this new set of ground rules, a new way of thinking must be instilled among all levels of management.

This model shows that new entrants to a global industry raise the level of competition, thereby reducing its attractiveness. Such media giants as Viacom, Disney, At&T have competitors, but they do not have a great influence on their global position. The presence of substitute services can lower service attractiveness and profitability as well as the price levels. Thus, many potential users prefer to use alternative (local) even if the price is low.

In this case the bargaining power of customers is crucial. The ultimate aim of customers is to pay the lowest possible price to obtain the services that they require. A source of customers power is the willingness and ability to achieve backward integration. Supplier power in the media industry is the converse of buyer power. Suppliers have enough leverage over industry firms, and raise prices high enough to significantly influence the profitability of their organizational customers. “

The largest suppliers of entertainment are the studios and independent producers in Hollywood, such as Warner Brothers and Carsey-Werner Productions. The supplier may or may not syndicate its own productions. A case in point is MGM. MGM” (Alexander 1998, p. 228).

The rivalry between existing competitors is strong. For substitution of service within media industry, switching costs are very low. For indirect substitutes (those provided by other industries), there are likely to be higher actual or perceived switching costs. “Opportunities with narrow-interest viewers have been developed to some extent in the cases of sports programming and programs related to business and finance, but the potential of specialized programming for specialized audiences is likely to continue to be a trend in the next several decades, and the syndication marketplace will benefit” (Alexander 1998, p. 229).

Vertical integration is traditional with media industries. Companies like Disney and Viacom that used to dominate the media segment are very vertically integrated. For an industry that is in a long-term growth phase, this is an excellent strategy. But once the industry matures, and growth begins to flatten out. They companies do not have the advantage of volume, but they have all the expense at each level of that integration, which they have to downsize to mature industry levels. Viacom follows backward integration strategies which help to gain greater control over the chain of services (Chan-Olmsted 1998).

Combining operations result in improved production and related economies. In some contexts, a key success factor is access to a supply of raw material, a part or another input factor—backward integration can reduce the risk (Hoskins et al 1997). Technology decisions involve whether new equipment will utilize existing versus new technology, the level of automation planned for existing and new equipment, and how closely equipment will be tied together.

Vertical integration decisions encompass the direction of integration and the balance of internal versus external capabilities. The intent is to achieve a competitive position in a narrow market segment, even though the company may not have a competitive position overall. Sales of the products have been extremely good over the past three years and have made a healthy contribution to the sales and profits of the business (Demers, 1999).

When a growth area emerges many companies wish to enter it, resulting in severe competition. In this case, they can create sustainable competitive advantage through collaborations and strategic alliances with other media giants. In strategic alliances ‘the production units’ of competing companies are integrated to enable economies of scale. Divestment by transferring the production of weak services is also a means of achieving scale economies.

It improves position of a company on the market and reduces its dependant on suppliers and customers. There are four elements of competition – quality, price, sales promotion and sales channels – and four competition strategies: product differentiation, market segmentation, cost leadership and the construction of entry barriers. The strength of these strategies depends on the company’s goals and its market position (Picard, 2002).

Example of Allied Media and Mercantile Advertising

The strategic alliance between Allied Media and Mercantile Advertising took place in 2007. For both companies, attractive from the standpoint of its level of growth, alliance is beneficial because it proposes new opportunities for market development. “Allied Media will offer Mercantile Advertising its entire media service, which would encompass strategic planning, media buying and implementation. This alliance is for its Rs 100 crore worth businesses” (Allied Media enters into strategic alliance with Mercantile Advertising 2007). As the most important, this strategic alliance allows both companies to expend their activities and enter new global markets. This strategic alliance enables firms to keep pace with technological advances. It allows the companies obtain new technology, to assist in its entry into a new market segment, and to provide the technical knowledge for the firm’s future product direction (Gross, 2002).

Sustainable Competitive Advantage

Sustainable competitive advantage is defined as “is the only reliable way to achieve superior performance” (Porter 1999, p. 202). If most of the firms in an industry are competitive in the sense of being able to make a profit and if they are not losing out to foreign competitors in foreign markets or their own market, they would consider themselves internationally competitive. “Sustainable competitive advantage allows the maintenance and improvement of the enterprise’s competitive position in the market. It is an advantage that enables business to survive against its competition over a long period of time” (Porter 1999, p. 54).

In media sector, companies become more competitive and they will need to reestablish interest and prestige in the service process and recapture the intrigue of how to do it better. Strategic alliances allow media companies to develop sustainable competitive advantage based on customers’ loyalty and brand recognition as a strong point of the market. Positioning strategy is one of the most influential factors in this industry. Positioning strategy is based on brand and product loyalty as an important factor in increasing the costs for customers of switching the products of new competitors.

Existing competitors are already obtaining substantial economies of scale, this have them an advantage over new competitors who are not able to match their lower unit costs of production. New competitors may find it difficult to gain access to delivering service, which will make it difficult to provide their service to customers or obtain the inputs required or find markets for their outputs. Following porter “the rate of learning may stem more from total industry learning than from the learning of one firm. Since a sustainable cost advantage results only from proprietary learning, 4 The term “experience” is often used to describe cost reduction over time” (Porter 1999, p. 78).

Sustainable competitive advantage in the media industry

Sustainable competitive advantage in the media industry today is driven more by sales and number of repeat customers, distribution and customer relationships than by manufacturing or product innovation. Constraint innovation and improvements require huge investments in R&D facilities. To remain competitive, market leaders spend billions of dollars on innovations and product developments. Many small competitors have to collaborate with media giants in order to sustain their market position and innovate. Products which are invested with high levels of technology require technical specialists for their sale and servicing.

Increasingly, as firms are prompted to improve their innovation and technological developments, they will prefer to internalize activities, both product and channel functions, to protect key technologies. As there is no clear relationship between the amount of money spent on R&D and the outcome of initiatives there is similarly no proof to support the idea that innovators of the past are likely to be the successful innovators of the future. R&D is cumulative, and this notion overlooks successful innovations made by firms. In addition, working with new suppliers is a risk of meeting deadlines. “Domestic rivalry helps keep firms innovative and striving for improvement” (Alexander et al 1998, p. 229).

Strategic alliances allow media companies to reach wide target market. Market size and wide target audience are the main opportunities for media providers. Non-price competition and cost differentiation create great opportunities for further growth and profitability. Media companies will sustain market position and create long-term relations with the consumers (Picard, 2002). It takes form: branding, advertising, promotion, and additional services to customers. Within the industry, cost and non-cost differentiation helps to create loyalty of local the customers. These “tools” will include: – temporary price reductions; – extra value offers, including offers relating to future purchase; premium offers (incentives), including free mail-in premiums, self-liquidating premiums ( Hollifield, 2001).

Case of AOL- Google Strategic Alliance

In 2005, AOL-Google announced a strategic alliance aimed to improve market position of both companies and collaborate in R&D. The alliance is a natural one; both companies have complementary experience in the Internet and media industries, and both wish to sustain the position on the international marketplace and compete against major international companies. “The agreement also calls for Google to provide some 300 million dollars worth of advertising on its web pages to AOL, and to feature AOL’s video offerings on Google Video, a way for users to find and view video programmes over the Internet.” (AOL, Google announce billion-dollar alliance 2005).

Given that the international marketplace is a turbulent one, management is capable of changing and adapting their strategies to current conditions. The fact that they duplicate the management structures of the parent utility indicated that they have established an inflexible system, incapable of managing in a changing environment.

This alliance’s focus on high-technology is not a casual development. There has been a significant economic dislocation in which the United States has lagged far behind other countries (Hull, 2000). The Japanese, long known for imitation, have turned to innovation as their big push into high-definition television demonstrates.

The future of AOL-Google strategic alliance lies in its ability to stand fast against foreign competition and to develop the goods and services that will be in demand in the twenty-first century. “This agreement is key to fulfilling our commitment to realize the potential of AOL’s very large online audience,’ said Time Warner chief executive Richard Parsons. ‘A critical piece of this strategic alliance will be our content, which we will be making more accessible to Google users” (AOL, Google announce billion-dollar alliance 2005).

AOL continues to possess the advantages of global market strength and product leadership that endow it with many future options. Manufacturing cost problems need to be squarely, fully, and promptly dealt with, and AOL must find the coherence it is searching for in the information systems businesses. Time Warner Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Dick Parsons comments: “We’re very pleased to build significantly on our special relationship with Google in a way that will meaningfully strengthen AOL’s position in the fast-growing online advertising business and help drive more advertisers to its Web properties. This agreement is key to fulfilling our commitment to realize the potential of AOL’s very large online audience” (Google Press Center 2007).

This case shows that it is important at this stage of the evaluation process to remain broad-based, including any business sector that may be remotely related or desirable. The most important criterion to apply correctly is that of strategic alliances. For example, this could include sectors containing products the firm has no expertise in or markets that the firm is not currently in but could be sold through the same distribution channels or could use the same techniques. It is important to note that throughout the selection process, the mission statement, goals, and objectives must either be reinforced or modified to coincide with the evolving strategy. AOL and Google create sustainable competitive advantage expending their market activities and improving technological resources, attracting wide target audience and creating new services for Google and AO: users.

The Supply Chain and Value Chain in the Media Sector

The supply chain for media has three main stages.

- The first stage is production or media content creation. It involves activities such as gathering new stories and writing books and articles, editing newspapers, composing and recording music, and so on.

- The second stage comprises packaging. The created content is incorporated into physical or digital components, collected together, and packaged assembled to a marketable media product.

- The final stage in the media value chain involves distribution of media products to consumers.

Some media products are supplied to consumers via traditional retail channels, some are transmitted to the audience via telecommunication infrastructure(e.g., television and radio broadcasting) and the Internet, and others are distributed via exclusive distribution channels (e.g., paper delivery)(Alexander et al 1998). Frequently in the literature the terms supply chain and value chain for the media sector are used interexchangely.

This is due to the fact the supply chain of the media sector corresponds to the concept of value chain introduced by Porter (Porter, 1998). As it has been defined by Porter, in the media where the chain of activities gives the products more added value than the sum of added values of all activities. E.g. Copying a CD may have a low cost but adds to much of the value of the end product, since a composed and recorded music without being packaged in a CD has less value. Moreover all stages in the supply chain are interdependent(Doyle, 2002).

This means that no single stage is more important than the others. However, if a company manages to monopolize any single stage of this chain it will gain a sustainable advantage over its rivals and become a gateway monopolist. The term “gateway monopolist” is used to describe concrete firms that gain control over some vital stage in the supply chain (Alexander et al 1998).

Therefore it is important for our later analysis. The strategies of different companies are examined under the aspect how the media companies try to reach such a position or preventing their competitors of gaining such a privilege. Moreover the regulators are trying to prevent a gateway monopolist and this is also has an influence on the companies strategies (Hoskins & McFadyen 1991).

Where the traditional value chain is effectively a series of interrelated functions within any organization that link its inputs to its outputs (outbound logistics, the sale of goods to customers), the media sector value chain refers to the value that can be generated by exploiting the information generated by any stage of this process. In this way, information, which in a physical value chain is merely one part of the supporting infrastructure, becomes, in a value chain, an end in itself and one which has commercial value (Porter 1998).

In addition to the issues raised by the examination of the traditional media value chain, there are further ones which occur due to the reconfiguration of this value chain as it is indicated by Wirtz, 2006. Wirtz argues that the reconfiguration of the value chain is driven by the convergence of the media, telecommunication, information and electronic commerce industries. This convergence itself is driven from Technological, Legal and Social factor which have been indicated in the PESTEL analysis.

Companies attempt through either strategic alliances to reposition themselves and reconfigure their value chain. Wirtz suggests that a company’s success depend on how successful this reconfiguration is executed.

Internal Capabilities and Resources

In media industry, a strategic alliance and collaboration can be considered as a mutual agreement of sorts between two firms to join together to become one company. For instance, one merging firm does not take on huge amounts of debt either to fend off or to purchase the other. Therefore, negative factors inherent in hostile takeovers are absent (Schiller, 1999). The possibility of massive sell-offs are usually not an issue.

There are, however, other factors common to alliance activities that must be considered, such as power struggles between the firms, a clash of corporate cultures, organizational and reorganizational issues, the effects of a new corporate direction, and entry into new or unfamiliar markets. A strategic alliance, therefore, like any other business activity, is not without its risks. Moreover, these risks can be managed and minimized (Jayakar & Waterman 2000).

An equitable distribution of resources is a critical ingredient to a successful strategic alliance. The commitment of resources that is to be made by the respective organizations must be made clear from the onset (Picard, 2002). The proper mix of resources, whether it is strictly financial or involves a commitment of manpower as well, must be defined from the very beginning. In fact, resource commitment is an integral part of any successful corporate strategy (Jayakar & Waterman 2000; Layton 2003).

To arrive at a strategy of proper resource allocation, an assessment must first be made as to what resources each organization brings to the strategic alliance and to the new corporate direction (Johnson & Scholes 2002, McQuivey & McQuivey 1998). Factors such as the size of the media organizations, facilities available, what resources are at their disposal, what long-term commitments are presently in place, assets, liabilities, and cash flow all come into play when assessing resource availability. Once these resources are located, the next step is determining which ones are usable. Not all resources may be needed after the strategic alliance.

They may not necessarily coincide with the new corporate strategy or there may be duplicates (McQuivey & McQuivey 1998). Media companies sustain competitive advantage if they obtain innovative resources and technology. Matching strategy to capabilities is the core of competitive advantage. One critical aspect to the success of a strategic alliance is having the experience and capabilities necessary to make it a success.

The strategic alliances in media industry provide cooperation to the two entities in the form of complementary strengths (Hollifield et al 2003). These collaborations can be translated for the customer into terms of consistent services and time, direct service, superior handling, flexibility in handling special requests, and responsive account representatives. If acquisition strategies are to succeed, they must create value.

The main thrust of any strategic alliances activity is to improve competitiveness. The question becomes one of whether the strategic alliances will be constructive, by the development of synergies and market efficiencies, or destructive, in the form of so-called creative destruction (Picard, 2002). Strategic alliances allow companies to improve their value chain and use resources efficiently.

Recommendations

First, there may be a situation where growth delivers a win-win situation to everyone, and as a result of the companies in the alliance increasing their sales, profits and satisfaction they may seek to add depth to the alliance by developing it further. Common goals are essential in alliances. For instance, AOL and Google are competitors in the business but they have been willing to cooperate fully in the development of advertising industry because this is a very expensive process. By sharing development costs and know-how they can gain a strong competitive edge over their competitors.

Both parties expect to benefit in almost equal terms, hence their’s is a win-win relationship (Picard, 2002). Mutual trust means that each partner can rely on the other even in the most difficult circumstances. This trust is based on past experience and a number of assumptions: that the reward will be in proportion to the contribution; that each partner has a key resource to offer and will remain committed to the alliance even in adverse situations by maintaining good mutual communications (Doyle, 2002). If there is trust, companies will cooperate even when there is a partial conflict of interest. Setting up a cooperative agreement involves a high degree of trust. For instance the alliance partners have to provide enough capital, competent personnel and the necessary knowledge to carry out the joint business (Chan-Olmsted, 1998).

Complementary capabilities and economies of scale can lead to worldwide competitive power. The products of alliances need to be competitive and sought-after if they are to be sold worldwide (Chan-Olmsted, 1998). Alliances can tend to create a sheltered, secure and stable environment because of the members’ monopolistic position. In collaborations and alliances there may well be factors that remain undisclosed. Not all technologies are disclosed to partners and some knowledge will remain confidential.

Ethical issues and responsibilities of both partners are crucial for success. Corporate ethics means complying with the norms or laws of society and consciously seeking to ensure that the business and its representatives do not engage in illegal or unfair practices. There are three arenas at which unethical behaviour is targeted: the primary environment or the market, the secondary environment, and the stakeholders. A recent development has been the establishment of codes of ethics. Strategic alliances should have such codes which stipulate that employees would be honest and loyal. Financial statements were manipulated to hide the losses, and in an attempt to make up the short-falls unsuccessful speculative investments were carried out, thus compounding the losses (Scherer & Ross 1990).

Conclusion

The information mentioned above shows that strategies alliances within media industry are crucial for success and a strong market position of the media companies. However, it is not just rational economics that drive this selection: it helps that R&D departments tend to be staffed by highly trained people with an interest in new technologies, people who have been selected to embrace and develop new ideas.

The examples of AOL-Google and Allied Media and Mercantile Advertising show that companies can compete on the global scale possessing competitive resources and capabilities. Successful strategic alliances combine the strength of two or more companies and create a core competence that cannot be attained by one company alone. In media sector, strategic alliances are very popular and have supported the rapid growth of many companies and enabled parallel enhancement of the technology.

Of all the functions in a media organisation, this is the one that should show the most natural inclination to embrace the new ideas of working within the media alliances can all be effective ways to improve the competitive position of an overall firm. However, any one of these processes must be an integral part of an ongoing corporate strategic plan. There must be some sort of synergy present in order for the strategy to make sense.

It is thus important to establish a systematic approach for assessing and evaluating a potential target so that a successful growth strategy can be developed. Key factors in alliance success are mutual trust, the existence of first-class complementary capabilities to create competitive core competencies and continuous mutual learning to enhance the core competencies. Alliances enable firms to develop capabilities that cannot be developed by a single firm, to bring about economies of scale, to outclass competitors by establishing de facto standards, and to avoid the risks inherent in large individual investments.

Bibliography

- Alexander, A., Owers, J., Carveth, R. 1998, Media Economics: Theory and Practice. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- AOL, Google announce billion-dollar alliance. 2005. Web.

- Allied Media enters into strategic alliance with Mercantile Advertising. 2007. Web.

- Chan-Olmsted, S.M. 1998, Mergers, Acquisitions, and Convergence: the Strategic Alliances of Broadcasting, Cable Television, and Telephone Services. Journal of Media Economics, vol. 11, iss. 3, pp. 33-36.

- Champlin, D., Knoedler, J. 2002, Operating in the Public Interest or in Pursuit of Private Profits? News in the Age of Media Consolidation. Journal of Economic Issues, vol. 36, iss. 2, pp. 459-469.

- Culpan, R. 2002, Global Business Alliances: Theory and Practice. Quorum Books.

- A Definition of the Media Sector. Reckon. 2008. Web.

- Demers, D. 1999, Global media: Menace or messiah? Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

- Doyle, G. 2002, Understanding media economics. London: Sage.

- Dupagne, M., & Waterman, D. 1998, Determinants of U. S. television fiction imports in Western Europe. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, vol 42, iss. 2, pp. 208–220.

- Gomery, D. 1995, Mass Media Merger Mania. American Journalism Review, vol. 17, iss. 10, p. 46.

- Gross, P. 2002, Entangled evolutions: Media and democratization in Eastern Europe. Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Press & Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Hollifield, C. A. 2001, Crossing borders: Media management research in a global media environment. Journal of Media Economics, vol. 14 iss. 3, pp. 133–146.

- Hollifield, C. A., Vlad, T., & Becker, L. B. 2003, The effects of international copyright law on national economic development. In L. B. Becker & T. Vlad (Eds.), Copyright and consequences: United States and Eastern European perspectives (pp. 163–202). New York: Hampton Press.

- Hoskins, C., & McFadyen, S. 1991, The U. S. competitive advantage in the global television market: Is it sustainable in the new broadcasting environment? Canadian Journal of Communication, vol. 16, iss. 2. Web.

- Hoskins, C., McFadyen, S., & Finn, A. 1997, Global television and film: An introduction to the economics of the business. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hull, G. P. 2000, The structure of the recorded music industry. In A. N. Greco (Ed.), The media and entertainment industries (pp. 76–98). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

- Jayakar, K. P., & Waterman, D. 2000, The economics of American movie exports: An empirical analysis. Journal of Media Economics, vol. 13, iss. 3, pp. 153–169.

- Johnson, G. and Scholes, K., 2002, Exploring Corporate Strategy: Text and Cases. 6th ed. Great Britain: Pearson Education Limited.

- Layton; Ch. 2003, News breakout. American Journalism Review, vol. 25, iss. 8, p. 18.

- McQuivey, J. L. McQuivey, M.K. 1998, Is It a Small Publishing World After All?: Media Monopolization of the Children’s Book Market, 1992-1995. Journal of Media Economics, vol. 11, iss. 4, pp. 35.

- Reed, S. F., & LaJoux, A. R. 1998, The art of M&A: A merger and acquisition handbook. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Rigby, D. 2007, Strategic Alliances. Web.

- Picard, R. 1990, Media economics. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Samuelson, P. (1976). Economics (10th ed). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Picard, R. 2002, The Economics of Financing of Media Companies (Business, Economics & Legal Studies). Fordham University Press; 1 edition.

- Porter, M. 1999, Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance. Free Press; 1 edition.

- Scherer, F. M., & Ross, D. 1990, Industrial market structure and economic performance (3rd ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Schiller, D. 1999, Digital capitalism: Networking the global market system. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Time Warner’s AOL and Google to Expand Strategic Alliance. Google Press Center. 2007. Web.

- Williams, D. 2002, Synergy Bias: Conglomerates and Promotion in the News Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, vol. 46, iss, 3, pp. 453.

- Wirtz.