Abstract

This report and the information presented in it is structurally a systematic review. Researchers note a systematic review “uses systematic and reproducible methods to identify, select and critically appraise all relevant research, and to collect and analyze data from the studies that are included in the review” (Systematic reviews in the health sciences, 2020, para. 1). This systematic review will observe articles on the topic of “of stress management in university students.”

Introduction

Students turn to various stress management tactics such as coping, psychotherapy, exercise, and pet therapy to minimize stress and anxiety patterns, and depression symptoms, which are due to many stress factors in the educational process.

It is possible to note that “at the most basic level, stress is our body’s response to pressures from a situation or life event” (Stress, 2020, para. 2). Researchers state that “stress has a way of becoming chronic as the worries of everyday living weigh us down” (What Is Stress Management? 2018, para. 5). Researchers are exploring the interconnectedness of stress management methods and stress levels of university students to identify the most effective strategy for improving the psychological state. The purpose of this systematic review is to investigate how stress management research techniques have changed in the PICOS framework and tendencies in stress levels and stress factors in the period of the last ten years.

Methodology

Eligibility Criteria

The eligibility criteria of selected studies of the systematic review are the PICOS (Population, Intervention, Control/Comparator, Outcome, and Study Design) framework. It is because “without a well-focused question, it can be very difficult and time-consuming to identify appropriate resources and search for relevant evidence” (PICO Framework, 2019, para. 1). The PICOS framework allows formulating the research question and selects the competent data sources and highlights information that interests the researcher. Studies should include university students as a population, socio-psychological surveys, and physical activities as interventions.

Pretest and posttest data and time frames as comparators and control should also be represented. Changes in stress, anxiety, and depression levels, found stress factors, and the difference between them serve as the outcome. The eligibility criteria for the systematic review are 2015-2020 and 2005-2010 years frames for studies. Such structures allow comparing research methods in the framework of the PICOS framework and the trends of stress management in university students. The publication status of this report is an academic paper, and the language is English, which is due to the condition of the international language of communication.

Information Sources

The information sources for this systematic review were the four largest databases, which are Google Scholar, Frontiers in Physiology, Taylor & Francis Online, and Z-Library. It is possible to note that “Google Scholar is a web search engine that specifically searches scholarly literature and academic resources” (What is Google Scholar and how do I use it? 2019, para. 1). According to official information, “Frontiers in Physiology is a leading journal in its field, publishing rigorously peer-reviewed research on the physiology of living systems” (Scope & mission, 2020, para. 1).

Authors note “Taylor & Francis partners with world-class authors, from leading scientists and researchers to scholars and professionals operating at the top of their fields” (About Taylor & Francis Group, 2020, para. 1). It is also possible to state that “Z-Library is one of the largest online libraries in the world that contains over 4,960,000 books and 77,100,000 articles” (Z-Library articles, 2020, para. 1). All the databases described above provide a massive layer of scientific information and use convenient and fast search engines, which the author of this systematic review last used on March 30, 2020.

Search

Electronic search strategy for Google Scholar:

- Enter keywords such as “stress, anxiety, depression, levels, management, university students” in the search bar;

- Click on “from 2016” or “select dates” and enter a specific time interval;

- Click on the title of the found study or the PDF version link on the right.

Electronic search strategy for Frontiers in Physiology:

- Enter keywords such as “stress, anxiety, depression, levels, management, university students” in the search bar;

- Select the “article” category and click on it;

- Click on the title of the found study;

- Download PDF version of the found article.

Electronic search strategy for Taylor & Francis Online:

- Enter keywords such as “stress, anxiety, depression, levels, management, university students” in the search bar;

- Select the “article” category and click on it;

- Select “Only show Open Access” point;

- Click on the title of the found study;

- Electronic search strategy for Z-Library.

Electronic search strategy for Z-Library:

- Select the “article” category and click on it;

- Enter keywords such as “stress, anxiety, depression, levels, management, university students” in the search bar;

- Select the “article” category and click on the title of the found study.

Study Selection

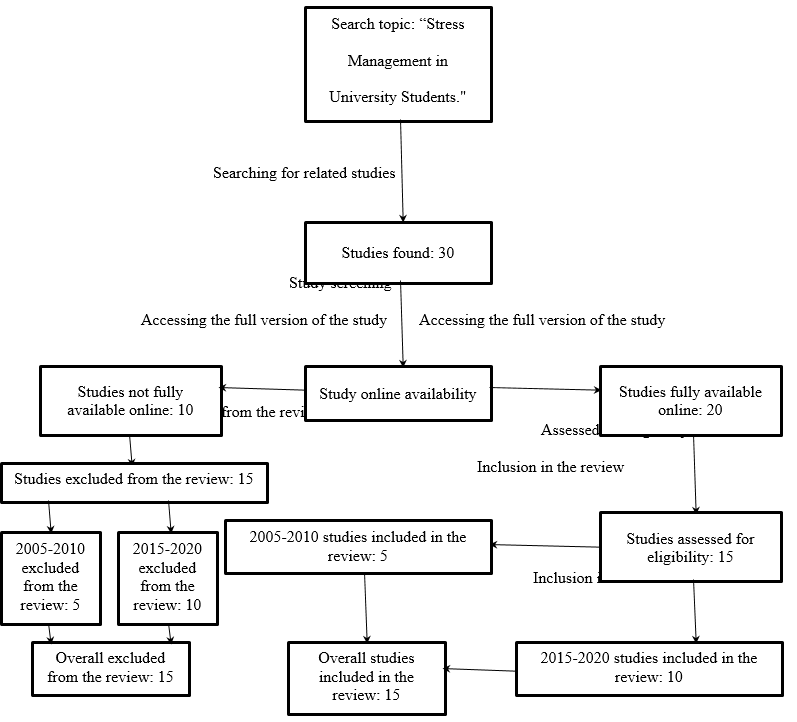

The method for selecting studies is PRISMA, which stands for Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. According to official information, “PRISMA is an evidence-based minimum set of items for reporting in systematic reviews and meta-analyses” (Welcome to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) website, 2015, para. 1). This methodology includes processes of screening (n = 30), eligibility (n = 30), exclusion from review (n = 15) and inclusion in review (n = 15).

Data Collection Process

Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Program) is a risk of bias assessment methodology in this systematic review. According to official information, “these checklists were designed to be used as educational pedagogic tools, as part of a workshop setting” (CASP Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2018, para. 4). It is essential to mention that the CASP Checklist for qualitative researches was selected among all tools to assess examined studies.

Results

Flow Diagram

2015-2020 studies excluded from the review:

- Ahmed, Z. and Julius, S. H. (2015). ‘Academic performance, resilience, depression, anxiety and stress among women college students’;

- Binfet, J. T. et al. (2018). ‘Reducing university students’ stress through a drop-in canine-therapy program’;

- Kaya, C. et al. (2015). ‘Stress and life satisfaction of Turkish college students’;

- Kim, S. H. and Choi, Y. N. (2017). ‘Correlation between stress and smartphone addiction in healthcare-related university students’;

- Kuang-Tsan, C. and Fu-Yuan, H. (2017). ‘Study on the relationship among university students’ life stress, smart mobile phone addiction, and life satisfaction’;

- Pengpid, S. and Peltzer, K. (2018). ‘Vigorous physical activity, perceived stress, sleep and mental health among university students from 23 low-and middle-income countries’;

- Song, Y. and Lindquist, R. (2015). ‘Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on depression, anxiety, stress and mindfulness in Korean nursing students’;

- Spadaro, K. C. and Hunker, D. F. (2016). ‘Exploring the effects of an online asynchronous mindfulness meditation intervention with nursing students on stress, mood, and cognition: a descriptive study’;

- Van der Riet, P. et al. (2015). ‘Piloting a stress management and mindfulness program for undergraduate nursing students: student feedback and lessons learned’;

- Zhao F. F. et al. (2015). ‘The study of perceived stress, coping strategy and self‐efficacy of Chinese undergraduate nursing students in clinical practice’.

2005-2010 studies excluded from the review:

- Deniz, M. (2006). ‘The relationships among coping with stress, life satisfaction, decision-making styles and decision self-esteem: an investigation with Turkish university students’;

- Dixon, S. K. and Kurpius, S. E. R. (2008). ‘Depression and college stress among university undergraduates: Do mattering and self-esteem make a difference?’;

- Dusselier, L. et al. (2005). ‘Personal, health, academic, and environmental predictors of stress for residence hall students’;

- Mercer, A., Warson, E. and Zhao, J. (2010). ’Visual journaling: An intervention to influence stress, anxiety and affect levels in medical students’;

- Segrin, C. et al. (2007). ‘Social skills, psychological well-being, and the mediating role of perceived stress’.

2015-2020 Study Data Summary

Beiter et al. (2015) examined Franciscan University undergraduate students (n = 374, 18-24 y/o) to verify the presence of stress, anxiety, and depression symptoms rates. The research methodology consists of a 21-question version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS21), everyday life concern factors rating, and demographic questions (Beiter et al., 2015, p. 90). The gender distribution of the population is females (63%) and males (37%). Surveys showed normal (62%, 60%, 67%), mild (12%, 15%, 10%), moderate (15%, 7%, 12%), severe (8%, 7%, 6%), or extremely severe (3%, 8%, 5%) presence of stress, anxiety and depression rates. The overall positive correlation among all categories is significant (P <.05). Prevailing stress groups are transfer (P <.01), upperclassmen (P <.05), and living off-campus students (P <.05).

Daltry (2015) explored acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) to improve the anxiety management of university students (n = 6). Some participants (n = 2) chose individual counseling, other Caucasian female undergraduate students (n = 4, 18-20 y/o) participated in group counseling. The research methodology includes the dependent sample t-test. During the nine-session therapy, students completed the Burns Anxiety Inventory, the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-2, the Distress Tolerance Scale (Daltry, 2015, p. 39). Results show the effectiveness of the therapy and significant difference (p =.005) between anxiety levels before (mean = 54.00, SD = 11.17) and after (mean = 24.00, SD = 14.07) the ACT.

Garett, Liu, and Young, (2017) examine freshmen students’ (n = 197) stress levels and their fluctuations depending on exams during the semester (Oct.-Dec.). The research methodology consists of General Linear Mixed-Model (Garett, Liu, and Young, 2017, p. 1). During the study (10 weeks), students were filling out personal stress reports. Analysis of the data showed that the stress level of first-year students varies during the average period of study (mean = 3.4, SD = 0.99), mid-term (mean = 3.57), and final examinations (mean = 3.95). Women are more susceptible to stress (mean + 0.2), and the relationship between stress indicators and the female gender is significant (p = 0.03). The most effective stress management tactic is exercise (p <.01).

Geng and Midford (2015) investigated the levels of stress among first-year university students (n = 139) undertaking teaching practicums, other years’ university students (n = 143), and factors contributing to stress disorders development. Researchers use the PSS-10 scale and online questionnaire methods (Geng and Midford, 2015, p. 1). First-year students experience (mean = 22.50, SD = 6.14) more severe stress rates than other years students (mean = 20.31, SD = 5.91). A significant difference (p <.01) is present among the stress rates of different years’ college students. The survey showed such basic predictors of stress as unawareness of mentors’ support (62.1%), university work commitment (51.7%), paid work outside university (35.5%), and performance assessment (14.3%).

Jafar, et al. (2016) conducted a study of students (n = 30) of the Islamic Azad University dividing them into experimental (n = 15) and control (n = 15) groups to determine the levels of anxiety. During the quasi-experimental intervention, students took part in Anxiety Inventory testing and then in stress management training (Jafar, et al., 2016, p. 47). Experimental group showed pretest (mean = 11.40, SD = 77.7), posttest (mean = 7.08, SD = 4.38), follow-up (8.61, SD = 4.5) anxiety levels. Control group showed pre-test (mean = 10.88, SD = 7.61), post-test (mean = 10.04, SD = 5.56), follow-up (10.08, SD = 8.32) anxiety levels. There are pretest-posttest (P < 0.01) and posttest-follow-up (P < 0.01) differences in anxiety rates in both groups.

Salam et al. (2015) examined the degree of stress and the common stress management tactics among medical students (n = 234) of the University Kebangsaan Malaysia. The main methods that the authors used in the study are observational. Students completed a standardized questionnaire related to subjective experiences and stress. The study shows the presence of stress (49%) among students.

The most susceptible to stress were third-year (mean = 6.41, SD = 3.69), female (mean = 7.00, SD = 4.12), and Malay (mean = 7.43, SD = 2.14) groups of students (Salam, A. et al., 2015, p. 171). The most frequent stress management tactic among third-year female (mean = 60.47, SD = 9.97) and Malay (mean = 59.83, SD = 10.45) groups is task-oriented. The least frequent stress management tactic among third-year female (mean = 42.61, SD = 9.20) and Malay (mean = 59.83, SD = 10.45) groups is emotion-oriented.

Saleh, Camart, and Romo (2017) investigated mental factors predictive of stress among college students (n = 483) in France. The age of the student population is ranked between 18-24 years (mean = 20.23, SD = 1.99). The primary survey method for research is online data collection based on Google Docs questionnaires and regression analyses (Saleh, Camart, and Romo, 2017, p.19). Students noted the presence of anxiety feelings (86.3%), depressive symptoms (79.3%), and psychological distress (72.9%). The main factors influencing the occurrence of stress disorders are the low sense of self-efficacy (62.7%), low self-esteem (57.6%), and little optimism (56.7%).

Samaha and Hawi (2016) studied the perceived stress and smartphone addiction interconnections among university students (n = 249). The population of students is partly male (54.2%) with the age range of 17-26 y/o (mean = 20.96, SD = 1.93). The methodology of the authors’ survey is Pearson correlations. Students completed Addiction Scale – Short Version, the Perceived Stress Scale, and the Satisfaction with Life Scale testing (Samaha, and Hawi, 2016, p. 321).

There are percentages of students with low risk (49.1%) of smartphone addiction and high risk (44.6%) of smartphone addiction. There are percentages of students with low perceived stress levels (53.4%) and high perceived stress levels (46.6%). Results show a non-significant positive correlation (p <.002) between perceived stress and smartphone addiction.

Wood et al. (2018) conducted a pet study of the effects of pet therapy involving dogs on the anxiety levels of university students (n = 131). Age of participants ranged from 18 to 35 years (mean = 19.92, SD = 2.60). The population of participants is composed of male (n = 35, 26.7%) and female (n = 96, mean = 73.3) representatives. Participants were tested before and after pet therapy intervention (15 min). The rates of anxiety before (mean = 43.16, SD = 10.56) and after (mean = 29.94, SD =9.94) dog therapy vary significantly (p < 0.001). Pet therapy involving dogs has a positive effect on reducing anxiety among Saint-Joseph University students.

Younes et al. (2016) examined the correlation and relationships between depressive syndromes, stress, and anxiety rates and Internet addiction among university students (n = 600). The participants from the university were only students of healthcare-related faculties. Researchers used methods such as DASS 21, the Rosenberg Self Esteem Scale (RSES), the Young Internet Addiction Test (YIAT), and the Insomnia Severity Index (Younes et al., 2016, p. 1). The cross-sectional questionnaire-based survey revealed average indicators of existing (mean = 30, SD = 18.474) and potential (16.8%) prevalence of Internet addiction. Potential Internet addiction is more often seen in men (23.6%) than in women (13.9%), therefore, varies greatly (p = 0.003). Potential internet addiction indicators have high correlation (p < 0.001) with stress disorders.

2015-2020 Studies Risk of Bias Assessment

2005-2010 Study Data Summary

Abdulghani (2008) explored the correlation between stress levels of King Saud University students (n = 600) and academic indicators such as academic years of education process and grades. The researcher chooses a voluntary questionnaire as research (Abdulghani, 2008, p. 569). Responding participants (n = 494, the mean age = 21.4, the SD age = 1.9) completed the Kessler10 stress inventory. The results show some students (57%) experience stress mild (21.5%), moderate (15.8%), and severe (19.6%) stress levels, others do not (43.1%). The association between stress levels and the first years of study is significant (p < 0.0001). %). The association between stress rates and academic grades is not significant (p = 0.46). The most frequent major stressors are the educational process (60.3%) and the environment (2.8%).

Bayram and Bilgel (2008) investigated the psychological state of university students (n = 1,617) in Turkey regarding anxiety, stress and depressive symptoms rates. There are male (44.4%) and female (55.6%) representatives of the mean ages of 20.7 (SD = 1.7) and 20.3 (S = 1.6) years. The primary research methodology is DASS-42 (Bayram and Bilgel, 2008, p. 667). Interviewed university students experience levels of stress (mean = 14.92, SD = 6.71), anxiety (mean = 9.83, SD = 5.94), and depression (mean = 10.03, SD = 6.88) levels. Women are much more likely to experience stress (p = 0.001), anxiety (p = 0.005). Freshmen also have elevated rates of stress (p = 0.044), anxiety (p = 0.000), and depressive syndromes (p = 0.003).

Dahlin, Joneborg, and Runeson (2005) examined the presence of depression and related stressors in Swedish students (n = 342) of the Karolinska Institute Medical University. During the study, responders (90.4%) completed the Higher Education Stress Inventory (HESI), the Major Depression Inventory (MDI), and Meehan’s suicidal ideation questions (Dahlin, Joneborg, and Runeson, 2005, p. 594). Students report depressive symptoms (12.9%) and suicide attempts (2.7%). Depressive symptoms prevail in the female group (16.1%) more than in the male (8.1%). The study showed that the most common stress factor is a lack of feedback.

Oman et al. (2008) studied the effect of moderated physical activity on stress levels among randomly selected university students. The research methodology consists of the pretest, moderate physical activity intervention (8 weeks), and posttest. Randomly selected groups of students took part in Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (n = 15), Easwaran’s Eight-Point Program (n = 14), and Wait-List Control (n = 15) (Oman et al., 2008, p. 569). Data analysis showed perceived stress levels (mean = 18.11, SD = 6.19) (mean = 18.11 – 2.41) decreased after moderation physical activity intervention with a significant difference (p =.099).

Shah et al. (2010) conducted a study (3 months) examined perceived stress levels of Pakistani university students (n = 200) of Medicine in CMH Lahore Medical College. Research methods are a cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey (PSS-14) and 33-item questionnaire. Results show respondents (n = 161, 80.5%) of both male (n = 53, 32.92%) and female (n = 108, 67.08%) groups of 17 – 25 years (mean = 20.35, SD = 1.09) experience stress (mean = 30.84, SD = 7.01). The female group (mean = 31.94, SD = 6.28) of respondents is more susceptible to stress than the male group (mean = 28.60, SD = 7.92). A significant difference between the two indicators is present (p < 0.05). The level of stress insignificantly negatively correlates with academic performance (p > 0.05).

2005-2010 Studies Risk of Bias

Discussion

Conclusions and Summary of Evidence

This systematic review examines ten scholarly articles over the past five scholarly years, five articles over the 2005-2010 years, and compares them from the perspectives of PICOS and stress management. An overview of all studies shows that the population in terms of social status, age, and gender groups has not changed over ten years. A comparison of the studies of Abdulghani, Bayram and Bilge, and Younes et al., Samaha, and Hawi shows an increase in intervention methods. The types of comparators and controls have also not changed, which is noticeable in the examples of Wood et al. and Oman et al. studies. A study of the findings of all studies shows that researchers use general principles for interpreting outcomes.

A comparison of the studies of Salam et al. and Shah et al. speak of a continuing trend of increased stress among women over the past ten years. In addition to the significant primary stressors associated with educational processes, studies by Younes et al., and Samaha and Hawi show the emergence of new factors, namely smartphones and the Internet. The works of Geng and Midford and Abdulghani mark the continued trend of a high level of stress among first-year students. Future research should be aimed at studying the reform of stress management methods to develop techniques for female students and first-year students.

Limitations

The fundamental limitations of a systematic review are the themes of stress management and university students. Another principal limitation of the systematic review is the periods of 2015-2020 and 2005-2010 years. The publication format of the reviewed works, namely, scientific articles also a limitation. Electronic databases as sources of information also represent the confines of the report. PICOS framework, PRISMA process, CASP risk of the bias assessment tool is also necessary to research limitations.

Reference List

Abdulghani, H. M. (2008). ‘Stress and depression among medical students: a cross-sectional study at a medical college in Saudi Arabia’, Pakistan journal of medical sciences, 24(1), pp. 12-17.

About Taylor & Francis Group (2020). Web.

Ahmed, Z. and Julius, S. H. (2015). ‘Academic performance, resilience, depression, anxiety and stress among women college students’, Indian journal of positive psychology, 6(4), p. 367.

Bayram, N. and Bilgel, N. (2008). ‘The prevalence and socio-demographic correlations of depression, anxiety and stress among a group of university students’, Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology, 43(8), pp. 667-672.

Beiter, R. et al. (2015). ‘The prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and stress in a sample of college students’, Journal of affective disorders, 173, pp. 90-96.

Binfet, J. T. et al. (2018). ‘Reducing university students’ stress through a drop-in canine-therapy program’, Journal of Mental Health, 27(3), pp. 197-204.

CASP Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2018) Web.

Dahlin, M., Joneborg, N. and Runeson, B. (2005). ‘Stress and depression among medical students: a cross‐sectional study’, Medical education, 39(6), pp. 594-604.

Daltry, R. M. (2015). ‘A case study: An ACT stress management group in a university counseling center’, Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 29(1), pp. 36-43.

Deniz, M. (2006). ‘The relationships among coping with stress, life satisfaction, decision-making styles and decision self-esteem: an investigation with Turkish university students’, Social Behavior and Personality: an international journal, 34(9), pp. 1161-1170.

Dixon, S. K. and Kurpius, S. E. R. (2008). ‘Depression and college stress among university undergraduates: Do mattering and self-esteem make a difference?’, Journal of College Student Development, 49(5), pp. 412-424.

Dusselier, L. et al. (2005). ‘Personal, health, academic, and environmental predictors of stress for residence hall students’, Journal of American college health, 54(1), pp. 15-24.

Garett, R., Liu, S. and Young, S. D. (2017). ‘A longitudinal analysis of stress among incoming college freshmen’, Journal of American college health, 65(5), pp. 331-338.

Geng, G. and Midford, R. (2015). ‘Investigating first-year education students’ stress level. Australian’, Journal of Teacher Education, 40(6), pp. 1-12.

Jafar, H. M. et al. (2016). ‘The effectiveness of group training of cbt-based stress management on anxiety, psychological hardiness and general self-efficacy among university students’, Global journal of health science, 8(6), pp. 47-54.

Kaya, C. et al. (2015). ‘Stress and life satisfaction of Turkish college students’, College Student Journal, 49(2), pp. 257-261.

Kim, S. H. and Choi, Y. N. (2017). ‘Correlation between stress and smartphone addiction in healthcare-related university students’, Journal of Korean Society of Dental Hygiene, 17(1), pp. 27-37.

Kuang-Tsan, C. and Fu-Yuan, H. (2017). ‘Study on the relationship among university students’ life stress, smart mobile phone addiction, and life satisfaction’, Journal of Adult Development, 24(2), pp. 109-118.

Mercer, A., Warson, E. and Zhao, J. (2010). ’Visual journaling: An intervention to influence stress, anxiety and affect levels in medical students’, The Arts in Psychotherapy, 37(2), pp. 143-148.

Oman, D. et al. (2008). ‘Meditation lowers stress and supports forgiveness among college students: a randomized controlled trial’, Journal of American college health, 56(5), pp. 569-578.

Pengpid, S. and Peltzer, K. (2018). ‘Vigorous physical activity, perceived stress, sleep and mental health among university students from 23 low-and middle-income countries’, International journal of adolescent medicine and health, p. 1

PICO Framework (2019) Web.

Salam, A. et al. (2015). ‘Stress among first and third-year medical students at University Kebangsaan Malaysia’, Pakistan journal of medical sciences, 31(1), pp. 169-173.

Saleh, D., Camart, N. and Romo, L. (2017). ‘Predictors of stress in college students’, Frontiers in psychology, 8, pp. 19-26.

Samaha, M. and Hawi, N. S. (2016). ‘Relationships among smartphone addiction, stress, academic performance, and satisfaction with life’, Computers in Human Behavior, 57, pp. 321-325.

Scope & mission (2020). Web.

Segrin, C. et al. (2007). ‘Social skills, psychological well-being, and the mediating role of perceived stress’, Anxiety, stress, and coping, 20(3), pp. 321-329.

Shah, M. et al. (2010). ‘Perceived stress, sources and severity of stress among medical undergraduates in a Pakistani medical school’, BMC medical education, 10(1), pp. 1-8.

Song, Y. and Lindquist, R. (2015). ‘Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on depression, anxiety, stress and mindfulness in Korean nursing students’, Nurse education today, 35(1), pp. 86-90.

Spadaro, K. C. and Hunker, D. F. (2016). ‘Exploring the effects of an online asynchronous mindfulness meditation intervention with nursing students on stress, mood, and cognition: A descriptive study’, Nurse education today, 39, pp. 163-169.

Stress (2020). Web.

Systematic reviews in the health sciences (2020). Web.

Van der Riet, P. et al. (2015). ‘Piloting a stress management and mindfulness program for undergraduate nursing students: student feedback and lessons learned’, Nurse Education Today, 35(1), pp. 44-49.

What is Google Scholar and how do I use it? (2019). Web.

What Is Stress Management? (2018) Web.

Welcome to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) website (2015). Web.

Wood, E. et al. (2018). ‘The feasibility of brief dog-assisted therapy on university students stress levels: the PAwS study’, Journal of Mental Health, 27(3), pp. 263-268.

Younes, F. et al. (2016). ‘Internet addiction and relationships with insomnia, anxiety, depression, Stress and self-esteem in university students: a cross-sectional designed study’, PLoS ONE, 11(9), pp. 1-13.

Zhao F. F. et al. (2015). ‘The study of perceived stress, coping strategy and self‐efficacy of Chinese undergraduate nursing students in clinical practice’, International journal of nursing practice, 21(4), pp. 401-409.

Z-Library articles (2020). Web.