Introduction

The ancient civilisations of Mesopotamia, Indus Valley and Egypt were formed around 5000 BC and are the first signs of civilised life in a world filled with barbarians and nomads. The Mesopotamian settlers settled in the fertile plains of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in what is modern Iraq and built large cities that were meticulously planned and managed. The large cities were surrounded by a network of smaller towns and villages that served the larger cities. This paper discusses the archaeological features and relationships between the larger cities of Mesopotamia and the smaller settlements in these regions.

About Sumerian and Akkadian Dynasties

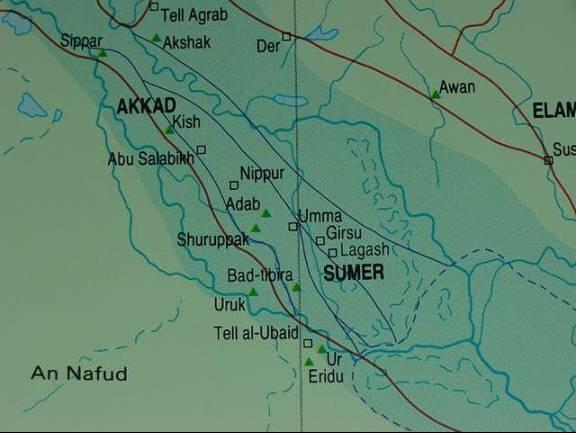

Pollock (1999) has suggested that records of Sumer can be traced to around 4000 BC and the civilization was located in the lower region of Mesopotamia. The lower regions of Mesopotamia have been attributed to giving birth to a number of dynasties. The concept of urbanisation, transportation, writing, planning and other concepts associated with modern civilisations started here. Pollock reports that there is a marked sequential oscillating cycle that varied between periods of fragmentation and centralisation. He suggests that the cycle started around 5000 BC and extended up to the Uruk era, towards the end of 4000 BC. The Akkad dynasty’s emergence came about in 2300 BC and decentralised in the lower regions of Mesopotamia and then it disintegrated after Gutian barbarians invaded it. The Akkadian king Ur II again attempted to centralise the rule and it fell apart in 2000 BC. Again Pollock (1992) has argued that the Mesopotamian civilisation was primarily agrarian and cultivated crops. They grew wheat, chickpeas, mustard, barley, lentils, leeks, dates, garlic, onions, lettuce and vegetables. The civilisations also practiced animal husbandry and raised domestic animals such as cattle, goats, pigs, sheep and that they used donkeys and oxen as the beasts of burden to till their lands and for personal transportations. In addition, these people also hunted birds, deer, fish and waterfowls. An illustration of the areas of Sumer and Akkad is shown in Figure 1.

Cities of Sumer and Akkad

Rothman (2001) has provided details of the cities in the region of Mesopotamia. There were a number of major independent cities and minor towns. The major cities acted as the prime centres of commerce and the nobility lived in these cities from where they governed the smaller cities and the settlement areas. The author has emphasised that not all the major cities existed at the same time and these cites waxed and waned in power and stature across the centuries. Each city was ruled by a King a priest and a governor and each city had a temple that was dedicated to a patron goddess or god who was supposed to look after the well-being of the city. He has mentioned the major cities as: Mari, Agade, Kish or Tell Uheimir & Ingharra; Borsippa or Birs Nimrud; Nippur or Nuffar; Isin or Ishan al-Bahriyat; Adab or Tell Bismaya; Shuruppak or Fara; Girsu or Tello; Lagash or Al-Hiba; Bad-Tibira or Al Medina; Uruk or Warka; Larsa or Tell as-Senkereh; Ur pr al Muqayyar and Eridu or Abu Shahrain. He has also mentioned a number of minor cities that owed allegiance to a major city that protected it from raiding barbarians. The minor cities or towns are: Sippar or Abu Habba; Kutha or Tell Ibrahim; Dilbat or Tell ed-Duleim; Marad or Wanna es Sadun; Kisurra or Abu Hatab; Zabala or Tell Ibzeikh; Umma or Tell Jokha; Kisiga or Tell el-Lahm; Awan; Hamazi; Eshnunna; Akshak and Zimbir.

The author has reported that warfare among the cities was a constant feature throughout the 2000 years and the people also used military sieges to starve out the people. A strong wall that sometimes deterred the enemy surrounded the cities. Life of the military was constantly spent in warding off barbarian invaders or nomads and fighting other cities. The enmity and fighting continued for more than three thousand years until the whole region was united by the Babylonians who then ruled the region with some semblance of peace. The Mesopotamians used spears, swords, shields and also used chariots in war.

Dynasties of Sumer and Akkad

Nissen (2002) speaks of the important dynasties that created and ruled different parts of Mesopotamia in the years 2000 to 3000 BC. The author has reported that the earliest period of recorded history goes back to 2900BC when the states of Sumerian rose to power. The power of the Sumerian kings ended when the Akkadain Dynasty came to power in 2400 BC. The Sumerians again rose to power in 2200 BC but were again ousted by the Amorites who invaded the region in 2000 BC. Around 1700 BC, the Babylonians came to power. The author has mentioned a number of dynasties that held power from 5300 BC to 2000 BC. The time line is: Ubaid reign from 5300 to 3900 BC; Uruk IV reign from 3900 to 3200 BC; Uruk III reign from 3200 to 2900 BC; Early Dynastic I reign from 2900 to 2800 BC; Early Dynastic reign from 2800 to 2334 BC; Lagash dynasty reign from 2550 to 2380 BC; Akkad dynasty reign from 2450 to 2250 BC; Gutian reign from 2500 to 2150 BC and the Ur III reign from 2150-2000 BC.

Urbanisation of the Cities

Algaze (2001) has used the example of the city of Urk to speak about urbanisation of the cities. The city had about 80,000 people who lived in the city that was about six square kilometres in size. In addition to a strong wall, the city had a system of bureaucrats, a highly stratified society and a strict military that protected the people. The author has reported that the surrounding plains of Khuzestan and Susiana were colonised by the people who formed small settlements that were guarded and protected by the city military. The agrarian settlers paid homage in the form of taxes. The city developed a network of traders that is controlled for many centuries. This was the biggest city in the world at that time and it seemed to become a hub for all trading activities as people from the other Arabian countries came to the city to trade. Gradually the power of the city extended to well beyond its immediate vicinity and the culture of sending armies across large distances and governing territories by remote force came into practice. The rulers managed to control territories in areas such as Turkey, Iran, Mediterranean sea and others.

About People and their Lives

Information about the population in cities, trades and agriculture practices used and other topics have been discussed in this section.

Population of the cities and Towns

Thompson (2004) has provided a detailed analysis of the demographic and population levels in various Mesopotamian cities during various eras. The author has suggested that around 3700 BC, there were around 3700 BC, only the city of Eridu had a population of 8000. Over the centuries, the number of cities that had more than 10,000 population slowly increased till it peaked to 300,000 in 2100 BC and then again it started going down. This fall in the population has been attributed to the loss of fertility in the soil, poor harvests, increased salinity of the soil over cultivation and so on and the fall in population seems to suggest that other areas soon opened up and where people could settle down. Table 1. shows the number of cities in Mesopotamia with a population of more than 10,000 and the table covers the years between 3600 BC to 2000 BC.

Trade in the Mesopotamian Region

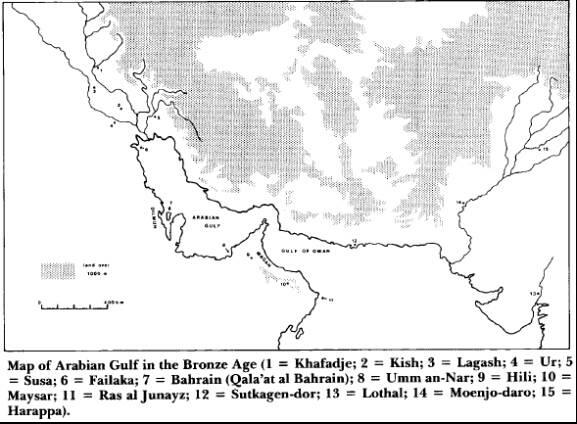

Edens (1992) has written about trade and commerce that flourished in the Mesopotamian regions. The author has suggested that the people were experts in using boats and small ships and travelled to far off regions such as Egypt, Indus valley and other regions to trade and barter. The author has reported that trade also existed between neighbouring states and cities and items such as food grains, pottery, metals such as copper were actively traded and bartered. The trade in the Arabian Gulf regions extended in certain geographical areas such as southern Mesopotamia and Elam that had port cities such as Lagash, Us and Susa; southern Lottoral and islands of the upper and central gulf such as the islands of Baharain and Failaka; the peninsular regions of south-eastern Arabia that enclosed the southern coastlines of lower Gulf and the Gulf of Oman and the mountain of interior Oman and the Indus valley civilisations with the coastal settlements between Sutkagen-Dor and Lothal with the river heartlands that included Harappa and Mohenjo Daro. The author has presented evidence in the form of Cuneiform tablets and figures that were principally of Mesopotamian origin. Figure 1 shows a map of the Arabian Gulf regions and the areas in which trade routes were established. Eden’s has also mentioned that the Mesopotamia regions had very few trees and stones and hence the buildings were primarily made from mud. He however reports that the temples and other structures were made from stones that were probably floated on barges and later hauled ashore.

Edens (1992) has also reported that conch shells that were carved intricately made were also found in different regions and these items were used as decorative items for houses and for the ships and also as mortuary accoutrements. The author has reported the Mesopotamia imported large amounts of copper and texts have been found that itemise individual shipments of 100 kilograms of copper and by 2500, more than 18 metric tons of copper was imported through the Gulf. The influx of large amounts of copper gave in the Akkadain period gave rise to the development of tools, personal objects, vessels, weapons, agricultural implements and other devices. Edens reports that the trade patterns closely followed the prosperity and contraction that has been observed. The trade also helped to distribute culture and acted as a medium of cultural exchange for the people. Edens has also written that the Mesopotamians exported items such as food grains, wool, textiles and in one shipment, about 2 metric tons of wool were exported. Wood was very much in demand in Mesopotamia and particularly species such as Cedar since there were very few trees in the region. The Mesopotamians used different types of boats such as skin boats that were made of reeds and animal skins; clinker built sailboats that were stitched with hair and used bitumen for waterproofing’ and wooden oared ships that people or animals who walked on the shore pulled along.

Life of the People

Algaze (2001) has researched that the early society of Mesopotamia has clear and sharp societal divisions with the priests and the noblemen being the upper class. All lands were in effect owned by these noblemen and they employed a number of serfs who worked hard in the fields. In addition, there were the trade people such as potters, tailors and the tradesmen who ventured into the Gulf to trade and bring in more goods. The author reports that life of the common people was very hard and they in fact led a life of sorrow and misery. Edens (1992) has reported that Barley assumed an important place in the diet of the common people. In the Ur III reign, massive amounts of barley were exported from Mesopotamia and trade documents cuneiform tablets that showed 7,14,000 litres of barley being exported have been found. Eden has reported that labourers were given about 2 litres of grains each day as diet. The city of Quala at al Bahrain was one of the biggest Bronze Age towns in the Gulf region and was about 20 hectares in size and had about 5000 people living inside the wall. The author has reported that about 714,000 litres of barley was consumed by the people in about 10 to 20 weeks. Sumerians and Akkadains worshiped a deity called as Enlil and the deity was considered as ‘Lord of the Ghost Land’. The deity had powers and it gave spells and chants to believers who could use them for good or evil purpose. Algaze has reported that slavery was in practice in the territories and captured slaves were made to work in the fields and as domestic help.

Irrigation and Agriculture

The Mesopotamians grew a number of crops by using irrigation techniques and features such as canals, weirs, dykes, reservoirs and shadufs were used with good effect. The fields were allowed to be flooded with the floodwater that brought in fresh alluvial soil. The fields were then tilled and sown with the required crop. Due to the high evaporation, over a period of time, the salinity became higher and so the farmers started growing Barley as it can tolerate rate more salt water. The Mesopotamians had developed advance techniques of calculations, record keeping and used cuneiform tablets to maintain detailed land records that showed who owned what, how much was grown each year, how much was owed to whom and so on (Algagze 2001)

Why the Civilisations Disintegrated

Noble (1994) has suggested that recent finding of archaeologists point to a devastating drought of 300 years that put an end to the Akkadian Mesopotamian civilisation. The abrupt climate change occurred around 2200 BCand totaly laid waste to the cities and turned the fields barren besides drying up the innumerable waterways. The people migrated in ever larger numbers to the southern cities that increased the burden on existing cities and caused their collapse. The change in weather pattern was abrupt and unpredictable and made thousands of people to set out of their cities in search for food and water. Other cities put up a strong resistance to prevent the Akkadians from entering and the author also speaks of a 110 mile that was set up to prevent the migrants from entering the cities. The turn of events wrested the power from the Akkadains and the Amorites rose to power, After a gap of 300 years, rains again came upon the deserted cities of the Akkadains and the soil could be cultivated again. But the power had shifted forever into the hands of the Amorites and King Hammurabi was the greatest of their rules who set up the famous code of Hammurabi that governed banking, trading, finance and other aspects of law.

References

Algaze, G (2001). Initial social complexity in southwestern Asia, Journal of Current Anthropology, Volume 42. pp: 199-233.

Edens Christopher (1992). Dynamics of Trade in the Ancient Mesopotamian “World System”. Journal of American Anthropologist. Volume 94. Issue 1. pp: 118-140.

Nissen, H (2002). Uruk, key site of the period and key site of the problem in J.N. postgate, ed artifacts of complexity, tracking the Uruk in the near east. London, BSAI: 1-16.

Noble Wilford John (1994). Collapse of Earliest Known Empire Is Linked to Long, Harsh Drought. The New York Times: NY. pg: C.1.

Pollock (1999). Ancient Mesopotamia, the Eden that never was. Cambridge, Cambridge University press.

Pollock, S (1992). Bureaucrats and managers, peasants and pastoralists, imperialists and traders, research on the Uruk and Jemdet Nasr periods in Mesopotamia. Journal of World Prehistory. Volume 6. pp: 297-336.

Rothman, M. S. ed 2001 Uruk Mesopotamian and its neighbors: cross cultural interactions in the era of state formation. Santa Fe school of American Research Press.

Thompson William R. (2004). Complexity, Diminishing Marginal Returns, and Serial Mesopotamian Fragmentation. Journal of World Systems Research. Volume 3. pp: 613-652.