Abstract

This paper examines the background and economic performance of the Target discount retail chain against Walmart as benchmark, by reason of the fact that the latter is the global leader and sets an example of numerous operating efficiencies in retail. Both are listed companies that rank in the top 28 of the Fortune 500.

The paper traces the origins and retailing experience of Target to 1903 in small town Minneapolis and shows how the chain began to take off only after embracing the still-popular discount mass merchandiser approach to retail. In the process of building and stocking hundreds of stores throughout the nation, Target appears to have gained operating efficiencies and sustained an ethical sense of HR management, despite important omissions in adopting logistical efficiencies that propelled the more aggressive category leader to its preeminent position today. An attempt is also made to carry out demand, cost and margin analysis based on the economic theory of the firm.

Introduction

Target Corporation is a mass-merchandise retailer with $65 billion in annual turnover as of end-2008, headquartered in Minneapolis and listed in the New York Stock Exchange (TGT). Under the “Target” and “Super Target” trademarks, retail operations are nationwide with the exception of Vermont.

Among discount retail chains, Target ranks second only to Wal-Mart Stores Inc., the latter boasting $404 billion in turnover (as of January 31, 2009 end of the company’s fiscal year) that makes it the world’s largest public company and largest private employer as well. Unlike Walmart (the trade name), Target has no foreign subsidiaries. Target Australia, also a discount retailer, merely licensed the trade name and logo.

Even as a far second in its industry, the revenue performance of Target is robust enough to land the chain 28th rank in the 2009 Fortune 500 and, by the same token, earn a place in the Standard & Poor 500 stock index.

History and Background of Target Stores

Like Walmart, Target had its start in the suburbs and obscure byways of rural America; both also took over existing retail concepts.

Target had much the earlier head start since continuous retail operations can be traced back to founder George Dayton taking over a tenant of his, the Goodfellows department store in 1903, nearly sixty years before the “Walton Five and Dime” came into being. Other than renaming the operation the “Dayton Dry Goods Company” and it again to the more concise Dayton Company in 1911, George Dayton seemed content with the solitary retail operation in Minneapolis.

Beginning in the 1950s, however, Dayton felt it was ready to participate in the great postwar boom that lifted the U.S. manufacturing and retail sectors. In quick succession, growth took the form of ranging far to acquire Lipman’s department store in Portland (OR), innovating with a world first – the Southdale completely-enclosed (and presumably air-conditioned) two-level shopping center, located in the Minneapolis suburb of Edina – and commencing chain operations with a second Dayton store nearby.

In 1962, the Dayton Co. acted on the advice of employee (and eventual partner John Geisse) to found the discount merchandise store named “Target ” to distinguish it from, and avoid cannibalizing, parent store business. The first branch opened in the Saint Paul suburb of Roseville. So optimistic was Dayton about the retail concept that three more stores were built around Minnesota before yearend. That same year, Sam Walton parlayed his long years of undercutting competitors with lower mark-ups at his “Walton’s Five and Dime” by seizing on the discount mass merchandise concept and opening the first “Wal-Mart Discount City” in Rogers (AR).

The four Target Stores went through three years of birthing pains and consistently lost money. In 1965, however, the group finally earned money on sales of $39 million and used the profits to fund a fifth store, also within the state. By 1967, Target had two more branches in Minnesota, branched out-of-state with two locations in Denver and gone public. Fairly rapidly, as of 1970, the company had diversified into in Mississippi, Texas, Oklahoma, Wisconsin, and Detroit, for a total of 24 stores and reaching the 24-location mark.

Since then, expansion continued along the same lines, leveraging both acquisition (e.g. Mervyn’s in 1978, Ayr-Way in 1980, FedMart in 1982, Gemco in 1986, Marshall Field’s in 1990, Fedco in 1999), organic growth, diversification into catalog-based direct marketing, establishing an e-commerce operation, and internally-generated geographical diversification.

As of 2009, Target boasted 1,683 stores all over the nation. This is just over a third of the 4,330 domestic Walmart locations as of October 2009, segmented into supercenters (62.5%), Discount Stores (20.4%), Sam’s Clubs (13.6%), and Neighborhood Markets (3.5%). In addition, the category leader boasts 2,980 branches in 14 other countries.

It is strong testimony to the sustainability of the discount mass merchandise retailing business that Target itself rode out the depths of the current recession by continuing to expand, opening 94 new branches (net of closings and relocations) in 2008 and 2009. This sustained effort at geographic expansion included arriving in Alaska and Hawaii at long last.

The Nature of the Industry

Differentiation

The nature of the discount retail industry means that there is little differentiation between the different discount retailers. Designed to compete on price, discount retailers do not have much leeway to lower their prices further to compete with other retailers with the same pricing model. Hence it is important for Target to establish its differentiation from other discount retailers. Target holds that it offers upscale, trend-forward merchandise at reasonable prices. Target believes that it is offering affordable prices because it reduces expenses related to bringing the goods to the customer and not necessarily procures shoddy goods. This is to be contrasted with the traditional model of discount stores which are primarily competing on prices by means that border on the ruthless and unethical. Walmart, for example, is notorious for paying low wages, uneven health insurance coverage, procuring goods from China, resisting unions, and going to the extent of opening up a procurement center in India from which the famous “$4 a prescription” drugs have been rolled out throughout Florida.

The familiar featureless “big box” appearance of discount retailers has given way to a degree of differentiation based on store exteriors and size. At Target, the standard store runs from 95,000 to 135,000 square feet (12,000 m²) sales floor area. Standard product assortment consists of hard goods, “softlines” (apparel), and some non-perishable groceries. In addition to the standard merchandise mix, Target stores offer seasonal merchandise, Target Pharmacy, Target Optical, Target Photo portrait studios, garden centers, the “Food Avenue” area for local food concessionaires, Starbucks, and a Pizza Hut Express.

The next larger branch type is “Target Greatland”, general merchandise superstores that are somewhat larger at 150,000 square feet in selling area. These have a wider variety of general merchandise than the basic Target Store but the space devoted to an adequate selection of groceries is neither consistent nor satisfactory.

SuperTarget hypermarkets, each roughly 175,000 sq ft in sales floor area, are the largest in the chain. The greater scope of the hypermarkets makes a complete selection of groceries, fresh produce, bakery and deli possible. Besides the usual food and photography concessionaires, hypermarkets house either a Wells Fargo Bank or U.S. Bank. Unlike direct competitors Wal-Mart Supercenters and Meijer, however, no SuperTargets offer late-night shopping.

Company Operations and Marketing

While clearly positioned in the discount retail business, this Target effort to differentiate itself from competitors attracts a younger customer base than its competitors. The average Target shopper is 41 years old, younger than the median age for any other discount store in competition with Target. Another way to differentiate itself from competitors is Target’s efforts to brand itself as a discount department store. Unlike other discount stores no music is played on the premises nor does it advertise in store using a public address system. Target malls also feature wider aisles, drop ceilings and cleaner fixtures which further help it distance itself from other discount stores.

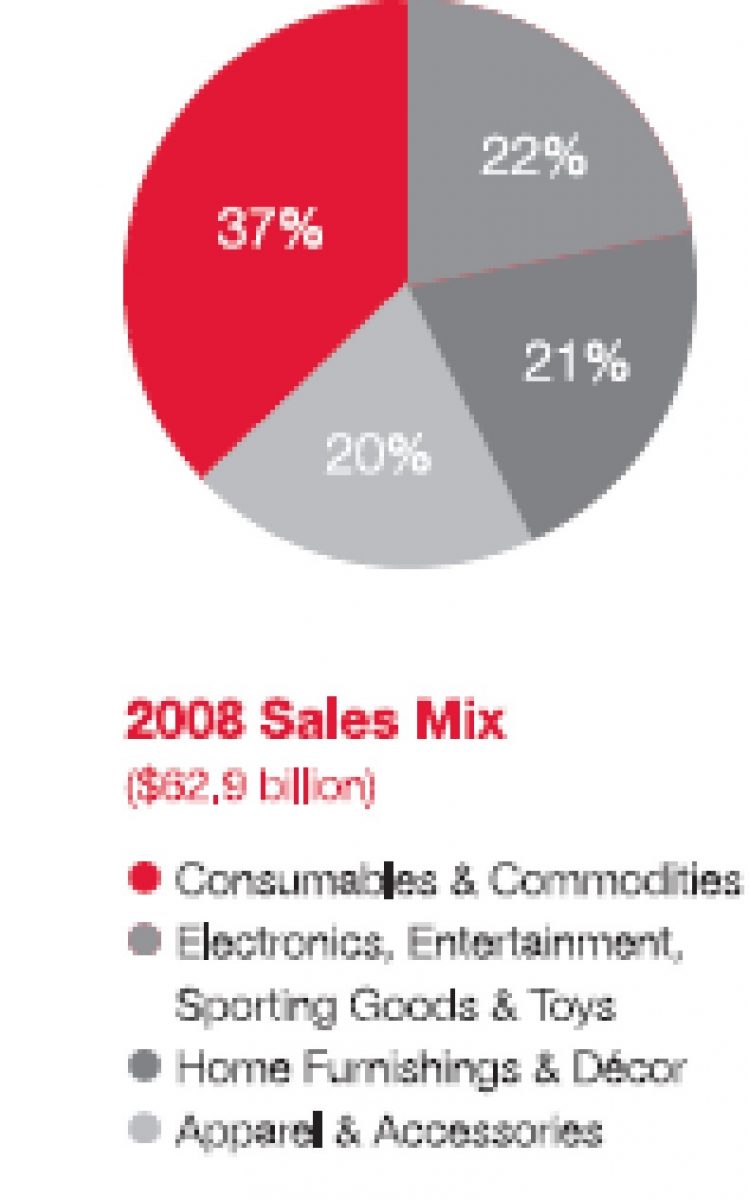

As a “full-service” discount department store, Target boasts a sales mix that is fairly evenly spread among toys and electronics, home furnishing, apparel and the food/beverage department. So-called “consumables and commodities” (essentially fresh produce, processed/canned and frozen food) comprise both a marketing opportunity and revenue constraint. The opportunity exists in that consumables are the traffic and frequency builders of any grocery type. But since there is little to distinguish steaks, turkeys and corn on the cob from those available at Safeway or Kmart, mark-up practices at Target must accommodate shoppers who are distinctly price-sensitive.

Target copes with this situation by, among others, maximizing the shelf space given over to house brands and building distribution centers in strategic locations around the country so as to reduce average transportation cost. As well, the essential viability of the department store model rests on maximizing share of every family’s shopping budget by offering the convenience of getting discretionary goods and the three other classes of dry goods under one roof and in one shopping trip.

Beyond this core appeal, Target maximizes revenue stream and margins with such allied operations as:

- Global supply chain –Target Sourcing Services/The Associated Merchandising Corporation (TSS/AMC). With 27 buying offices, 48 quality-control units, seven commissionaires and staffing of 1,200 dispersed the globe, TSS locates dry-goods merchandise everywhere; evaluate suppliers’ factories for quality, labor and transshipment issues.

- Target Financial Services (TFS) operates the Target National Bank that is the official issuer for Target REDcard, Target VISA, the Target Check Card debit card, and the Target Loyalty Card; and monitors GiftCard (gift certificate balances).

- Target Brands, which has direct responsibility for all of the chain’s private label and house brands such as Archer Farms and Market Pantry processed foods, the Sutton & Dodge line of premium meats, and Trutech electronic appliances.

- Target.com, the e-commerce operation that is ran independently from the retail chain. Among others, target.com is a useful channel for earning the last bit of revenue out of seasonal overruns and house brands.

- Daring to take over even the tenant shopper services kiosks that clog every mall and superstore around the country. In 2005, for example, Target took over the photo labs of Eastman Kodak subsidiary Qualex in all stores. While continuing to use Kodak equipment and processing supplies, the chain has linked up with Yahoo! Photos, Photobucket and Shutterfly.

Demand Analysis

Demand analysis serves two primary managerial objectives. First, it provides insights to properly manage demand and second, it helps forecast the sales and revenue portion of a firm’s cash flow stream. Demand relationships are best represented in the form of a schedule (table), graph or algebraic function. The demand analysis is one of the most important factors when evaluating the company’s financial position from an economic standpoint. It is also the simplest form of demand relationship.

Target Corporation sells a wide variety of products and services in its retail segment. Analysis of any one product would be counter-productive. For example, analysis of Tide detergent sales of Target would not be informative since Tide is also sold in other major retailers like Walmart. Total sales revenue is available in its annual report. Also available is the Gross Margin which is the result of dividing the gross margin dollars by sales. The Gross Margin is the best indicator of price vis-à-vis total sales. Since Target is a retailer of consumer goods and for the most part simply passes on the products from the manufacturer, its Gross Margin is essentially its mark-up and total sales represents quantity sold. Thus, the elasticity function can be applied using two figures as substitutes. After all it is projected that at some point raising their margin too high will result in a drastic decline in revenues as customers chose to purchase the products from other retailers who in turn purchased them from the manufacturer at the same price.

Table 1: Annual Sales and Gross Margins

It can be noted that the gross margin has stayed fairly constant during the entire period covered. This indicates Target Corporation’s unwillingness to drastically alter its pricing model. Instead, changes in actual prices of goods at Target are the direct result of increases in the price charged by the manufacturers. Any increase in sales and therefore revenue are the direct result of increased volume which is a function of the number of customers.

Table 2

In the absence of information about unit sales/demand, it has not been possible to estimate demand curves and elasticities. However, one notes from the financial highlights in Table 2 above that Target may be the more efficiently managed company. Though the scale of operations is very different – Target has only four stores domestically for every ten of Walmart’s, the latter has more than four times as many locations on a global basis, Target turnover is just 16% that of Walmart, the leader rings up an average of $54.9 million per store compared to $37.4 million for Target, and Walmart grew three times faster even in the depths of the recession – the disparity in operating income and earnings per share is decidedly much narrower than one would expect.

Target follows a cost-plus profit and pricing strategy. This owes to the fact that other retailers can easily be substituted for Target if they chose to price their products too high. After all, most of Target’s retail items are available in other major retailers. Target’s products are highly elastic. It is also difficult to quantify brand loyalty to Target as a brand (unless one has access to “Guest Card” and loyalty program statistics) since there is little to stop customers from shifting their business to other retailers. Every item in Target, save perhaps for private label brands sourced via exclusive suppliers abroad, can easily be substituted with similar merchandise offered by competitors.

Elasticity is given by the following formula

As mentioned, given the nature of Target’s business, unit price cannot be obtained. Target sells a wide variety of products at competitive prices. Hence price for Target is best represented by its gross margin. Quantity demanded can be obtained using the sales revenue of the company from its pure retailing operations.

Demand for Target itself as a retailer is highly elastic. The chain cannot change prices too drastically without affecting demand. Among the explanations for this is the ready availability of many substitutes. Furthermore, majority of goods available at Target are consumable products as opposed to durable goods. Consumables are empirically inelastic.

When the Price Elasticity of Demand of a product is greater than one in absolute value, the demand is said to be elastic; thus, it is highly responsive to price change. Demand with an elasticity of zero is said to be perfectly inelastic therefore the demand is completely unresponsive to price change. When a demand has an elasticity that is less than one in absolute value, it is said to be inelastic, suggesting that the demand is weakly responsive to price changes.

Cost Analysis

The Discount Store industry model is relatively simple but highly competitive. There is little actual differentiation between one company and another. Target’s cost structure consists of many expenses that correlate directly and indirectly to their marketing, production and sale of discount consumer goods. These expenses are; Cost of goods sold, marketing, selling and administrative expenses, advertising and promotion expenditures, restructuring and litigation charges. A large portion of Target’s cost structure is consumed by the cost of procuring the goods that are sold in the stores. Only 30% of the total average price of a product goes to the gross profit of the firm; more than two-thirds (70%) goes to the cost of the products sold.

Managers are interested in the economic cost of resources used. Economic cost refers to the cost of attracting a resource from its next best alternative use (i.e. opportunity cost). Managers seeking to make the most efficient use of resources to maximize value are concerned with both short term and long term opportunity costs. The short run cost-output relationships can help managers to plan the most profitable level of output, given the capital resources that are immediately available. Long-run cost – output relationships involve attracting additional capital to expand or contract the plant size and change the scale of operations.

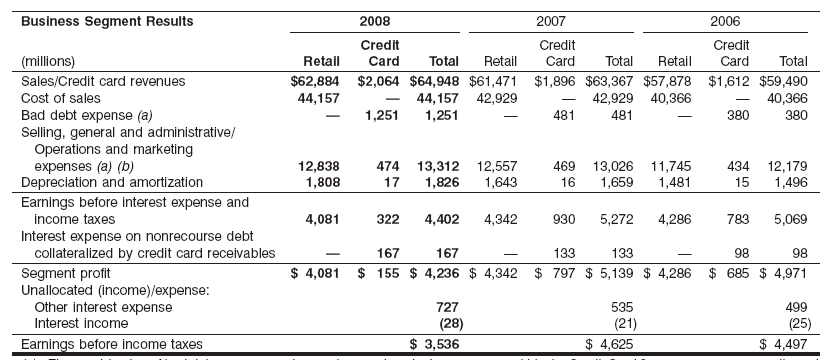

Target is no exception to this fundamental economic principle. The 2008 total operating costs for the Target business segment, where the retail division belongs, is shown below. (Target Corp., 2009, p. 71)

The business segment includes all of Target’s business units. This includes its credit card revenues as well as its retail business. The retail segment is difficult to quantify due to the very large number of products Target sells to consumers. Target also has in-house brands in addition to branded goods from domestic manufacturers. However, Target’s financial reports do not publish per product sales or revenues and instead lumps it all into the category retail sales.

Using the information from the above figure the simple marginal revenue and marginal costs can be derived. To simplify the analysis, the entire retail business has been assumed to be one product.

Given the highly competitive nature of the Discount store industry, Target faces a demand (D) curve that is identical to its Marginal revenue curve (MR), and this is a horizontal line at a price determined by industry supply and demand.

Profit Analysis

Both Walmart and Target belong to the Retail industry under the Discount store section. Both companies are dominant in their industry. In fact, they are number one and two respectively in their industry. However, other competitors have significant share in the industry as well. Barring any differentiation, both companies are in perfect competition. The cut-throat industry where they belong has numerous substitutes and they are forced to compete on the basis of price.

Target Economic Profit

The following format was used to compute the economic profit of Target

Economic profit = Total Revenue – Total Cost

- 2005 Economic Profit = $52,620 Million – $50,212 Million = $2,408 Million

- 2006 Economic Profit = $59,490 Million – $56,703 Million = $ 2,787 Million

- 2007 Economic Profit = $63,367 Million – $60,518 Million = $2,849 Million

- 2008 Economic Profit = $64,948 Million – $62,824 Million = $2,214 Million

It can be seen that the recession has had a negative effect on Target’s otherwise constant growth over the last four years. Total revenues grew apace with total costs largely because Target’s price plan is based on their total costs in bringing the products to the consumer.

Conclusion

The Target chain traces its origin and experience in department store retailing to early in the last century. For many decades, however, growth was slow. By comparison, the benchmark chosen, discount mass merchandise industry leader Walmart seized on the “big box” concept quickly, seized on efficient logistical methods, and grew much faster from the sixties to the present to become the largest publicly-listed company and largest private employer on a global basis. Target has also expanded energetically since the late sixties and early seventies but is just one-sixth the size of Walmart today by revenue.

Two things stand out in this brief economic analysis. First, economic profit at Target shrunk somewhat during 2008, arguably the worst of the current recession, because operating costs climbed faster that moribund total revenue. Despite the substantial disparity in their respective scales of operation, secondly, Target may be the more efficiently-managed chain.

For the rest, given the sheer diversity of products each carries and the fact that volume turnover is not part of regulatory reports, it has not been possible to calculate precisely the required demand and cost analyses.

References

Rowley, L. (2003). On Target: How the world’s hottest retailer hit a bull’s-eye. Hoboken, (NJ): John Wiley & Sons.

Target Corporation (2009). Annual report. Web.

Walmart Stores.com (2009). Annual report. Web.