Introduction

There is increased interaction among people from all around the globe compared to the twentieth century. Globalization has, In turn, influenced the culture and well-being of people in their communities. This paper examines the various dimensions of culture and the influence of cross culture communications on global business operations.

Communication and culture

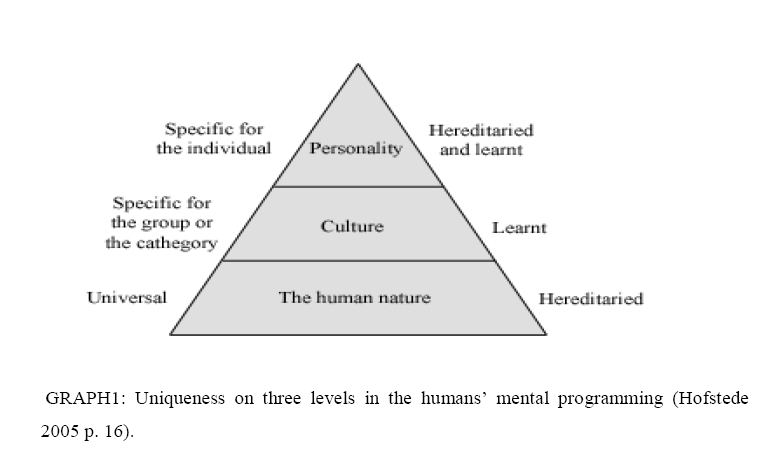

According to Hofstede (2001), there are about 400 definitions of the word “culture”, though they can be summed up to imply the way a group of people lives. This is noticeable from their values, rituals and heroes. As such, culture refers to the wide spectrum that entails learned human behavior patterns that are independent of a person’s nature and personality. Graph 1 shows the uniqueness of culture.

Graph1: distinctiveness of individuals’ mental training (Hofstede, 2001)

Consequently, one needs to examine an individual’s behavior against their culture, in order to comprehend their communication patterns. This is because one’s mindset is defined by the cultural practices of an individual.

According to Agar (1994), most researchers look at culture in a national level with little regard of the numerous cultural differences due to ethnicity within a nation. While people from one country may portray similarities in various cultural traits, an in depth analysis shows that individuals have diverse ideals and standards depending on their customs and location within a country.

Hofstede’s national cultural model

Geert Hofstede came up with four dimensional national culture models following his study of employees at IBM. His data was based on over 11000 questionnaires that he obtained from 72 countries and 20 languages. The research by Hofstede was based on the analysis of the role of employee values in attaining the company objectives.

The first dimension by Hofstede was Power distance (PD), which showed the scope of equal power distribution within a society. In addition to this, the Power distance Index analyzes the level to which the society accepts this distribution of power. In his evaluation of organizations and institutions as society units, Hofstede realized that it was inevitable to have a significant level of disparity of the individuals’ talents and knowhow.

Consequently, Hofstede categorized power distance in a cultural setting as either low or high. A high power distance is indicated by communication flow from top to bottom and more reward for higher authority levels.

The second dimension examines the degree to which individuals of a culture choose to operate as individuals or collectively as a group. This dimension of individualism versus collectivism identifies the degree to which the interests of an individual outweigh the interests of the group.

In his third dimension, Hofstede looks at the values of a society with regard to masculinity and femininity.

According to Hofstede (2001), masculine cultures are dependent on the men providing for, and protecting the family, whereby the society focuses on income, acknowledgment and courage. On the other hand, feminine cultures hold the expectations of both men and women equally, whereby the society focuses on favorable working relationships, collaboration and employment security.

The fourth dimension, uncertainty avoidance, evaluates the scope to which individuals are at ease with controlled circumstances, based on their customs. Societies that seek high uncertainty avoidance are more comfortable with rules and regulations that administer the rights and duties of both employers and employees.

Hofstede added a fifth dimension, “long-term versus short-term orientation, which looks at cultural attitudes towards the past, present and future” (Hofstede, 2001). According to Hofstede, individuals in a low Long Term Orientation culture are less likely to value tradition, compared to others. Hence, they are more open to change as long as they are fully involved in the innovation project (Straub, Loch, Evaristo, Karahanna, & Strite, 2002).

While the research by Hofstede is widely used by many scholars and practitioners, some researchers argue that Hofstede’s results were obtained from sparse and flawed samples. However, there are some researchers like Søndergaard, who analysed the predictions by Hofstede, and confirmed most of them to be valid.

Hofstede’s work was especially beneficial to organizations that were expanding their businesses globally, since there was little work on culture in the 1990s (Straub, Loch, Evaristo, Karahanna, & Strite, 2002).

According to Gudykunst (2003), the cultural dimensions by Hofstede are flawed since the deductions were based on the analyzed from a single company. Gudykunst (2003) argues that the results of a single company cannot be used to generalize the cultural system of a country.

In addition to this, he argues that national divisions do not provide appropriate units of analysis since borders do not limit cultures. However, Agar (1994) affirms that cultures are divided across national lines, as indicated by the Arabic cultures. Hofstede also supported his research by stating that national identities provided the best means of evaluating and examining cultural variations (Hofstede, 2001).

Trompenaars’ cultural business model

Contrary to the research conducted by Hofstede, the research by Trompenaars covered 15,000 people from multiple companies in fifty countries. Based on the data obtained, Trompenaars came up with seven fundamental dimensions of culture (Trompenaars & Hampden-Turner, 2005).

Trompenaars argues that time is a key dimension of culture since it allows both groups and individuals to coordinate their activities. The individual’s perception of time as either a precise value or an approximation helps in the planning of organizational duties.

This attitude towards time is dependent on the cultural perception of past experiences, present-orientations and future orientations (Trompenaars & Hampden-Turner, 2005). In his second dimension, Trompenaars argues that individuals from affective cultures are demonstrative.

Consequently, their communication is spontaneous, and may appear as aggressive for neutral people, who prefer to control their feelings and expressions instead of displaying them in public.

Trompenaars also noted the distinction between individuals from universalistic and particularistic cultures. He noted that while universalistic individuals were concerned with following rules in life, the particularistic individuals favored friendships and relationships to codes and standards.

In his fourth dimension, Trompenaars noted that individualistic cultures required that individuals prioritize themselves and their families over culture or organizations. He identified that employees in an organization were required to exercise Communitarianism, in order to achieve the organization objectives. In return, the success of the organization would influence the employees, therefore, benefiting them eventually.

Trompenaars noted that individuals from specific cultures were friendly and open with people on limited aspects of their lives. On the contrary, diffuse cultures allowed individuals to share all their details once they were comfortable with the other individuals.

As a result, diffuse culture managers were observed to be more approachable than those from specific cultures. Trompenaars also noted the possibility of organizational conflicts due to clashes between people from ascribed and achievement cultures, whose opinions varied in the ability to accomplish a task.

Based on his seventh dimension, Trompenaars noted that international companies faced challenges when people from externalistic cultures worked with those from internalistic cultures. While the former prefer to solve disagreements by holding free deliberations, individuals from internalistic cultures avoid confrontations (Trompenaars & Hampden-Turner, 2005).

Conclusion

The dissimilarities between Hofstede’s and Trompenaars’ deductions of cultural dimensions are due to the variation in the choice of analysis variables. While Hofstede studies the variables of national culture, Trompenaars analyses the course of culture development. Research on various cultural dimensions by the two philosophers show varies response.

For instance, a study of Power Distance in Lower Silesia Chamber of Commerce, in Poland showed that the organizational management was not domineering, but rather participative.

This was due to the few management levels, which limited the horizontal flow of information. The study confirmed Hofstede’s second cultural dimension since the individuals preferred to work individually, because Poland is an individualistic society.

With regard to the affective versus Neutral dimension by Tromenaars, the study of organizational culture in Poland, which is an affective culture, showed that the organization had work ethics that required employees to refrain from showing emotion in the workplace. However, the employees stated that they were expressive in their private lives.

With regard to time, it was noted that punctuality was valued, though the management was not keen about monitoring the employee time. In conclusion, research shows that cultural values are more evident in society than in the organization. This is because organizations structure their work ethics and regulations based on the consideration of various cultures in the workplace.

Employees in global organizations also learn to accomodate other cultures due to their exposure to foreign cultures. Hence, the various dimensions of culture do not apply in all situations, but depend on the availability a stronger code that governs human behavior, like the organizational code of conduct.

References

Agar, M. (1994). Language shock: Understanding the culture of conversation. New York: William Morrow and Company.

Gudykunst, W. B. (2003). Cross-cultural and Intercultural Communication. Fullerton: SAGE Publications Inc.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations across Nations, Second edition. London: Sage Publication.

Straub, D., Loch, K., Evaristo, R., Karahanna, E., & Strite, M. (2002). Toward a theory-based measurement of culture. Journal of Global Information Management, 10(1), 13-23.

Trompenaars, F., & Hampden-Turner, C. (2005). Riding the Waves of culture. Understanding cultural diversity in business. London: Nicholas Brealey.