Among the fundamental inventions that have revolutionized the writing instrument industry is the ballpoint pen. This instrument which has a plastic casing runs ink on paper from a plastic reservoir thanks to a metallic ball that rotates within a metallic cavity. Of note, the ball is a metallic alloy of brass, a mixture of copper and zinc. This material is preferred due to the fact that it is corrosive-free, easy to model and it’s appealing to the eye. A suitable ink for this instrument should be particle-free, thick and slow to dry in the cartridge. As such, the ink (oleic-based) incorporates such materials as “dye, lubricants, surfactants, thickeners, and preservatives” (Peeler 64). The cartridge and casing are made from thermoplastics- high density polyethylene (HDPE). This essay explores the geological information of the raw materials, the processing steps and the environmental issues.

With respect to the brass ball, its constituents (copper and zinc) are naturally occurring elements. Zinc is mostly found in the earth’s crust, and comes inform of mineral compounds or metal deposits. As deposits they occur as volcanic hosted massive sulphides (VHMS), carbonate hosted, sedex deposits or intrusion related. As minerals, they occur as sphalerite (ZnS), marmatite, calamite, pyrite or franklinite. Zinc is mined from open pits or underground, with metallic ores of sphalerite accounting for 95% of the available zinc ores mined. The ore is concentrated via a roasting (sintering) process at 900oC, and as such, ZnS is converted to ZnO.

The product is then fed into a hydrometallurgical process where the ore is purified and extracted using electrolysis method to obtain pure zinc (99.9%). This is stripped off, “dried, melted and cast into ingots” (Trebilcock 141). On the other hand, the most abundant deposits of copper are chalcopyrite (CuFeS2). These deposits are classified as either igneous (porphyry) or sedimentary depending on the occurrence. The processes for recovering it from its ore involve a chemical concentration process (froth floatation) which achieves 98-99% copper, followed by a purification process which is done via electrolysis to achieve a pure metal. With the raw materials ready, brass is obtained from a mixture of the two, with copper dominating the composition (between 55 to 95%). The process involves melting (1,050oC), hot rolling, annealing and, a final rolling to obtain a ductile and recyclable product.

With regards to the ink, the basic component, oleic acid, is obtained from plants e.g. olive fruits and nuts. The remaining components are organic in nature, obtained from different parts of a plant. To process it, the components are mixed at different ratios, heated to enhance mixing before it’s cooled and hence ready for use.

The HDPE is a petrochemical product obtained from a polymerization reaction courtesy of Ziegler process. The raw materials for the process include “aluminum triethyl, a metal alkyl, and titanium tetrachloride, an organometallic” (Carraher 7). All these components are mined before they are reacted to form a final product. Ethane, the main component in aluminum triethyl, is refined from natural gas. Titanium primarily occurs as mineral deposits of titanite, rutile and brookite. On the other hand, aluminum deposits occur as bauxite (Al2O3 and alumina). Ziegler process produces HDPE which can easily be remodeled.

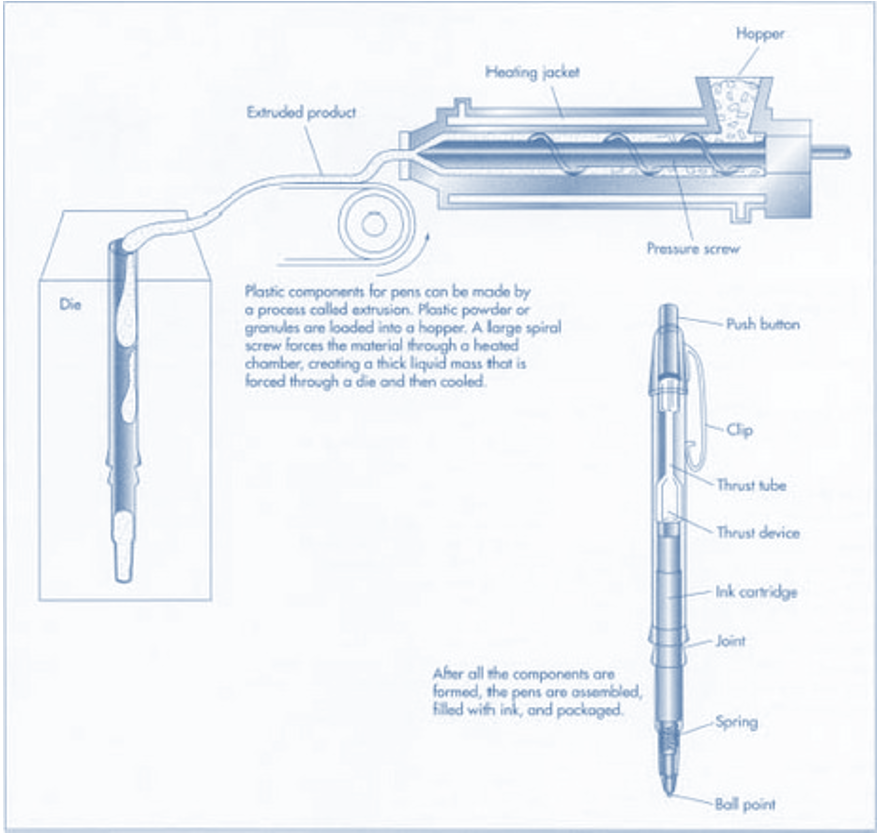

The manufacturing process of a pen involves a stepwise process starting with ink making. This step runs concurrently with the making of the brass balls which are later mounted in ballpoint sockets. At the same time, the housing and ink reservoir are made by extrusion/injection method, with HDPE granules serving as raw materials (Fig. 1). The ink is then injected in the reservoir before a ballpoint is fitted. The final product is complete after the housing has been inserted. This is packed in boxes awaiting shipment.

The environmental hazard posed by this equipment is that most of its parts are toxic and non-biodegradable (HDPE); however, these can be mitigated through recycling of the plastics.

Works Cited

Carraher, Charles. Polymer Chemistry. South Melbourne, Victoria: Thomson Learning, 1992. Print.

Peeler, Tom. “The Ball-Point’s Bad Beginnings.” Invention & Technology 6.3 (1996): 64. Print.

Trebilcock, Bob. “The Leaky Legacy of John J. Loud.” Yankee 7.8 (1989): 141. Print.