Introduction

Many things that China is known for in modern-day and significant parts of its culture formed during the formidable years of the Song dynasty rule. Coming to power in 926 and ruling until 1276, the Song dynasty sought to strategically reunify China, which had been split apart by warlords and regions fighting among each other. The unification and innovative governance reforms led to an age of enlightenment and prosperity, China’s ‘Renaissance’ moment. The country rapidly propelled forward in technology, scholarship, economics, demographics, and culture, establishing it as a regional power. The Song dynasty (926-1276 AD) brought about a commercial revolution and prosperous society that had profound changes in Chinese history and culture.

Governance Reforms and Policies

Emperor Taizu was the first Song ruler and focused his efforts on politically unifying China and laying the foundations for future prosperity. By the time of his death in 976, all but two kingdoms were united under one rule (Lorge, 2015). The first reforms began almost a century later under Emperor Renzong. Led by scholars Fan Zhongyan and Ouyang Xiu, these initial reforms became known as the Qingli Reforms or Minor Reforms. Zhongyan proposed a ten-point program which focused on improving government efficiency, raising the standard of examinations, defense, agriculture, and education. However, the reforms largely failed, due to the lack of full support from the emperor and large landowners, with the only positive outcome was the establishment of a national educational system in China. This took place between 1043 and 1045 (Lorge, 2015).

Nevertheless, the efforts of Zhongyan and others were not in vain as three decades later, Wang Anshi, a minister under Emperor Shenzong, built upon their foundation. Anshi led what is now known as the New Policies or Xifeng Reforms lasting from 1069 to 1076. The key to these reforms was the use of Confucian principles as a means of addressing and solving key issues for the government and society.

The New Policies focused on three categories of state finance and commerce, defense, and education/governance. Anshi advocated that government officials must be competent and trained, with men holding positions for which they were most qualified and best fit. He created the Three College system at the National University, which future officials from all prefectures had to attend, and where they were rigorously tested, replacing the previous prefectural examination system (Drechsler, 2013).

For defense, Anshi introduced the Baojia system, a local village security policy. It called for the organization of small-to-medium-sized groups of essentially militia in villages and towns. They exercised police powers, night watch, and local defense, relieving the prefecture governments of administrative and fiscal duties to support small-scale operations. There were also reforms to the army, with the creation of mixed force units of 3000 men, known as commands law, that sought to improve the relationship between officials and common troops (Pease, 2021).

Finally, Anshi introduced major economic and market changes. It introduced the equal tax law based on land ownership to collect taxes from major landowners that typically avoided paying them. Major shifts in agricultural policy were seen, such as the green sprouts law, with the government loaning money to peasants to buy seeds, and the hydraulic works law that focused on building local irrigation systems. On the market, the balanced delivery law sought to control expenditures and price ceilings for commodities, and the market exchange law targeted major merchants and guilds, which disrupted price manipulations and market fluctuations (Pease, 2021).

Technological Breakthroughs

With the reorganization of government, education, and the market, China saw significant technological progress. These breakthroughs came as a result of both domestic investment into education and international trade bringing new innovations back to China. There were breakthroughs in agriculture as a result of the above policies, with rice becoming a major feeding crop for the Chinese population. As an outcome of maritime trade, shipbuilding greatly improved alongside mapmaking and compass navigation. Manufacturing saw progress through new uses for gunpowder, porcelain production, and the invention of mechanical objects. Scholarship, culture, and science made great progress with the availability of printing and support of artists by the government (Paludan, 1998). Virtually all industries benefited from it.

Demographic and Commercial Growth

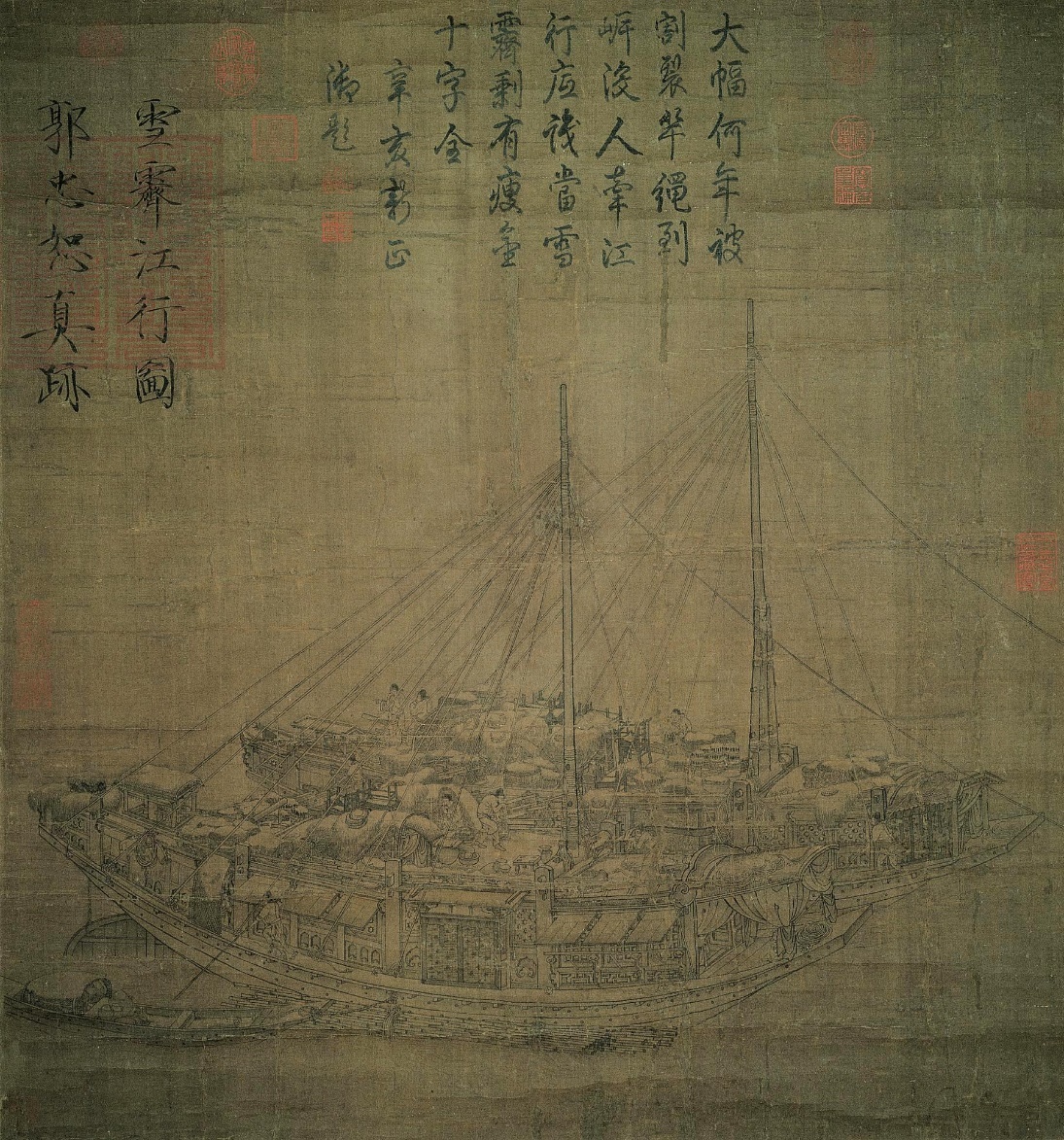

Government efficiency and economic policies began to have an effect and resulted in economic growth. Authority was centralized with the administration, but for a period, it led to a period of strict control, preventing abuse and corruption. As agricultural policies took effect, there was a food surplus, and farmers had the ability to expand their families. The number of registered households nearly doubled to 97 million in China by 1020 (Chen and Kung, 2019). Aided by technological advancement, Chinese ships were the most advanced in the world for its time, able to carry high volumes of cargo, greatly contributing to the expansion of trade, particularly with Arabs who also saw flourishment with the rise of Islam. Export revenues rose from 500,000 strings of cash in 960 to nearly 65 million in 1189 (Agyekum, 2019).

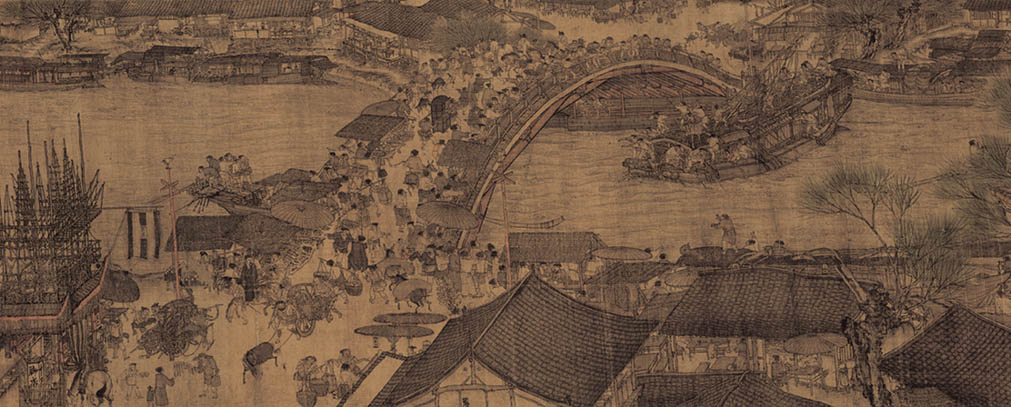

With the growth of commerce, cities shifted from being purely administrative units to large commercial centers bustling with activity and attracting the best market and cultural entities. Urbanization occurred as people sought jobs in the new market economy. Private trade greatly increased commerce, conducted not only in official markets but throughout the city and its suburbs. It was an age of luxury, and elegant living was now enjoyed by a much wider class, not just aristocracy. Even the peasants and lower class felt the impacts with greater availability of food and entertainment (Paludan, 1998). General satisfaction was high, and China was by far the richest nation in the world at the peak of the Song dynasty, which made the period known as the ‘commercial revolution.’

Issues and Downfall

As with any period of great prosperity in history, the Song dynasty’s rule came to an end. By the end of the 11th century, the dynasty saw a degeneration of imperial leaders and fiscal problems that were largely self-caused. The Jin invaded Northern China, forcing the Song southward, albeit they continued to see several more decades of stability and prosperity. Eventually, the government positions that were so critical to the positive changes and were meant to attract competent administrators became corrupt as people bought their way into power. The wealthy merchants that prospered from years of economic growth found means to avoid taxes or regulation.

In order to compensate, the government levied taxes on peasants, which began to rebel. There was an evident socioeconomic class divide that was rapidly increasing, and that was unhealthy for any society. At this time, China also faced the continuous threat of invasion from inner-Asia tribes and lacked the military strength to respond.

The Song dynasty fell ironically due to misplaced trust. In 1233, the Song dynasty allied with the Mongols, sharing territories south of the Yellow River. The Songs sought to defeat their long-time adversaries, the Jin, whose emperor was defending in Caizhou. The allied force was able to jointly capture the stronghold. However, soon after, in 1235, the Mongol’s turned on the Song dynasty. In several stages, the Mongols gradually overtook Chinese territories until the final defeat of the Song in 1276. At this point, the Mongols took over rule in China and established the Yuan dynasty.

Conclusion

The Song dynasty and their fundamental changes to governance and politics of unification led to a period of social and economic changes in China. This period of increased growth, innovation, and prosperity became known as the Song ‘commercial revolution.’ It was truly a time for significant shifts in Chinese social demographics, economy, and culture. Although some issues did persist, it was a truly unique period that generated progress.

References

Agyekum, Ivy K. 2019. “Commercial Revolution” in the Song Dynasty. Journal of Literature and Art Studies 9 (10): 1093–1098. Web.

Chen, Ting, and James Kai-sing Kung. 2019. Why the Song Dynasty? The Rise of A Merchant Class And The Emergence Of Meritocracy In China. Web.

Drechsler, Wolfgang. 2013. “Wang Anshi and the Origins of Modern Public Management in Song Dynasty China.” Public Money & Management 33 (5): 353–60. Web.

Lorge, Peter. 2015. The Reunification of China: Peace through War under the Song Dynasty. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Paludan, Ann. 1998. Chronicle of the Chinese Emperors: The Reign-by-reign Record of the Rulers of Imperial China. London: Thames & Hudson.

Pease, Jonathan O. 2021. His Stubbornship: Prime Minister Wang Anshi (1021–1086), Reformer and Poet. Leiden: Brill.