Introduction

The primacy of armed conflict in the evolution of the Western world is the essential tragedy of modern history. On the one hand, war has helped create the oases of stability known as states. On the other hand, it has made the state a potential Frankenstein monster, an instrument of unconstrained force. The mass state, the regulatory state, the welfare state—in short, the collectivist state— is an offspring of total warfare.

Bruce D. Porter, War and the Rise of the State

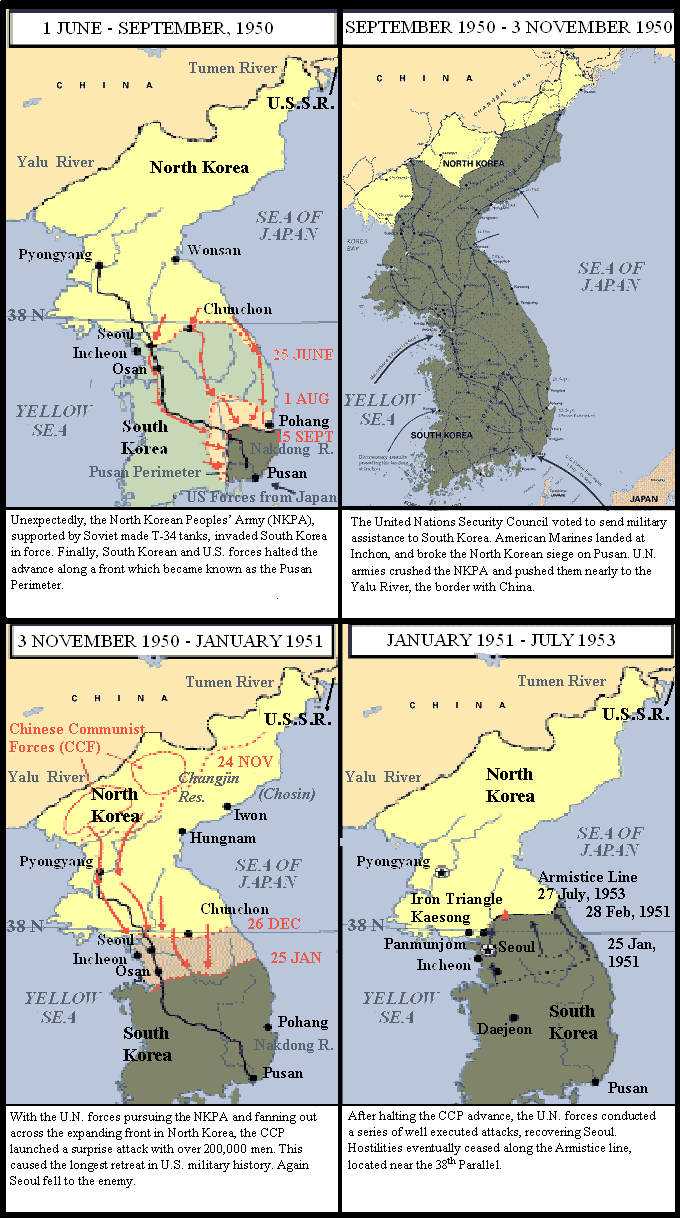

After the USSR established a Communist government in North Korea in September 1948, that government encouraged and supported the revolution in South Korea in an effort to bring down the recognized government and gain control over the entire Korean peninsula. Not quite two years later, after the revolution showed signs of failing, the northern government undertook a direct attack, sending the North Korea People’s Army south across the 38th parallel before daylight on Sunday, June 25, 1950. The assault, in a narrow sense, marked the start of a civil war between peoples of a divided country. In a larger meaning, the cold war between the Great Power blocs had erupted in open hostilities.

The war is a conflict between South and North Korea that started on June 25, 1950, and lasted till July 27, 1953, though the official war ending was not proclaimed. This conflict of the period of Cold War is regarded as an indirect war between the USA with its allies with the forces of CPR (Chinese Peoples Republic) and the USSR. The northern coalition included the forces of North Korea and its armed forces; Chinese army (as according to official data it is considered that China did not take part in the conflict, regular Chinese forces were formally regarded as “Chinese people’s volunteers”); USSR which also did not participate in the war openly, but undertaken its financing, and also sent units of Air forces and lots of experts and specialists to the Korean peninsula.

South Korea, the USA, Great Britain, and the Philippines participated from the side of the South. Lots of countries were involved as peacemaking forces under the UNO auspices.

Main body

The North Korean army crossed the border with its southern neighbor under the coverage of artillery on June 25, 1950. The incidence of land troops, trained by soviet military experts included 135 thousand soldiers and 150 T-34 tanks. The government of North Korea announced that “Betrayer” Rhee Syngman had invaded the territory of the DPRK (Democratic People’s Republic of Korea). The advancement of the North Korean army in the first days of the war was rather successful. Nearly two-thirds of North Korean troops of the 40 thousand armies were not ready for war, and by the 28 of June Seoul (the capital of South Korea) had been captured. The main attack directions included also Kaesong, Chuncheon, Uijeongbu, and Nanjing. The Seoul airport Kimpho had been destroyed completely. Though the main aim – Blitz Craig had not been achieved, Rhee Syngman and most of the South Korean government managed to survive and leave the city. Mass revolt, which the North Korean leaders relied on, did not happen. However, 90% of South Korea had been captured by the DPRK army by mid-august.

The attack on South Korea became rather surprising for the USA and other western countries: a week before the invasion (June 20) Dean Acheson, from the State department in asserted in his report, that the war is unlikely. Harry Truman had been reported about the war several hours after its beginning. In spite of the after-war US army demobilization, which had weakened the US positions in the region (except the US Marine Corps, divisions sent to Korea were complimented for only 40%), the still USA had possessed a large military contingent under the command of General Douglas McArthur in Japan. Any other state did not have such great military power in the region, except the United Kingdom.

Truman ordered McArthur to provide military equipment for the South Korean army and conduct the evacuation of the USA citizens under the coverage of aviation. Truman did not consider it necessary to start air war but ordered the Seventh Fleet to arrange the defense of Taiwan, thus ceasing the policy of non-interference in the rivalry of Chinese communists and Chan Kaishi forces. Kuomintang government (now located in Taiwan), asked for military assistance, but the USA government declined the request, motivating it with the possibility of communist China interference in the conflict.

The UNO Security Council was convened in New York on June 25. The agenda included only the Korean issue. The initial resolution, proposed by the Americans, was adopted by the nine “for” votes, with the absence of “against”. The Yugoslavian plenipotentiary hold and Soviet ambassador Jacob Malik were absent. He boycotted the Security Council sessions by the direction of Moscow, because of the refusal to declare communist China instead of the nationalistic government of Chan Kaishi.

Other western countries supported the USA decision and rendered military help to American troops, which were sent to help South Korea. However, the alien troops had been driven back far to the south to the region of Pusan by the middle of august. In spite of the help from the side of UNO, American and South Korean forces could not manage to disentangle from the ring, also known as Pusan Perimeter. They could only stabilize the front line along the Naktogan river. It seemed that DPRK forces would experience no difficulties in invading the whole peninsula, but aliens managed to launch the offensive.

The most important operations of the first months of the War are the Tejong attack operation (3-25 of June) and the Naktogan operation (July 26 – August 20). Some infantry divisions, artillery regiments, and some smaller armed formations of DPRK acted in the Tejong operation. North coalition managed to conduct a forced crossing of Kimgan river, surround and separate into two parts the 24th American infantry division, and to capture its commander major-general, Dean, as a prisoner. As a result, American forces lost 32 thousand soldiers and officers, more than 220 main guns and mine-throwers, 20 tanks, 540 machine guns, 1300 auto cars, and others.

The 25th infantry and mechanized American divisions experience great damages during the Naktogan operation in the region of the Naktogan river. Korean People’s Army (KPA) defeated the driving back parts of the South Korean army, captured the southwestern and Southern parts of Korea, and approached Masan, thus making the 1st American division of Marine Corps drive back to Pusan. The offense of North Korean troops was stopped on august, 20. Southern coalition reserved the Pusan springboard up to 120 kilometers along the frontline, and up to 100-120 km in-depth, and could defend it rather successfully. All the attempts by the DPRK army did not succeed.

Meanwhile, Southern coalition troops got the enforcement by the beginning of autumn and started trying to break the Pusan perimeter. The general counterattack started on September 15th.

Overview of the conflict

The great paradox of The Korean Conflict was that at the time the North Koreans attacked South Korea, most Americans had never heard of Korea. The Korean peninsula, furthermore, was not part of an American defense perimeter in East Asia that Secretary of State Dean Acheson had illustrated in a speech to the National Press Association just six months earlier. Moreover, even though the Korean Conflict severely upped the context of the Cold War and led to twenty years of particularly bitter relations between the United States and Communist China (People’s Republic of China or the PRC), neither the Soviet Union nor the PRC had been particularly worried to have North Korea attack South Korea.

The motives for the outbreak of warfare on June 25 and the response it created are far more explainable today than they were nearly fifty or even fifteen years ago. For one thing, it is now clear that the Korean War was a piece of a long-lasting civil conflict in Korea since the end of World War II. During most of the twentieth century, Korea had been controlled by Japan as a colony, which main aim was to produce rice. Although Korea had a long, nearly 2,000 years history, the Japanese had tried to eliminate all relics of Korean national identity. But they had not succeeded. After the war, lots of groups sought to presume the mantle of leadership. Everybody believed that Korea, which, according to the achieved agreement immediately after the end of the war in August, must be occupied above the 38th parallel by the Soviet Union and below that line by the United States, should be joined up and given its sovereignty. Otherwise, they were separated ideologically and politically. On the one hand was the traditionalist elite of landowners, businessmen, and manufacturers who had enjoyed a privileged status under Japanese rule that they sought to retain. On the other were political leftists, including large numbers of peasants and workers, who expected fundamental changes in the social and political structure of Korea. Even before World War II officially ended in August 1945, conflicts had taken place between the conflicting groups as workers and peasant unions and communist strength grew.

This situation was faced by the American occupation troops under the rule of Lieutenant General John Hodge when it landed in September 1945. Hodge’s directions were to not recognize any political group as the lawful government of Korea but instead to continue with the establishment of an American military government (AMG). Disturbed by the political and social chaos he found in Korea, however, Hodge was soon working closely with rightist elements, particularly with Rhee Syngman, a stubborn Korean nationalist who had spent most of his life in the United States working for Korean autonomy. Hodge believed that Rhee stood for the best chance to restore order and stability in Korea.

By every evaluation used in public view polls, the Korean War was one of the most unpopular wars ever lead by the United States. It had a huge influence on US foreign policy and on its citizens. During the three years of warfare, this war that cost in excess of $100 billion took approximately 54,000 American lives, and about 150,000 wounded. The deaths among the Koreans and Chinese must be calculated in the millions. As George Donelson Moss notes in his book, Moving On ( 1994), the Korean War turned the cold war into a shooting one. No longer merely an ideological rivalry, the cold war became deadly for Americans, as well as others. This transformation and the victims might have been acceptable if the war had been won, but the long negotiations ended in a draw at best. Annoyance and irritation over the consequences of this “limited war” distinguished the typical American attitude toward participation in the Korean war. In August 1953, according to data saved in Hazel Erskine’s article, “The Polls: Is War a Mistake?” (1970), 62 percent agreed that the war in Korea had not been worth fighting. When did resistance to the war occur? Who was against this war, and why? What were the effects of this opposition on President Harry S. Truman and the United States?

When North Korea attacked South Korea in June 1950, President Harry Truman reacted quickly. With China which became communistic in 1949, Truman did not wish the Republicans to have an extra issue in the upcoming off-year elections. Bypassing Congress for fear that prolonged discussions might allow Kim Il-Sung’s arms to take control over the whole country, the president went to the United Nations for support to send troops to help the struggling forces of South Korea. The UN agreed because the Soviet Union, as it had been mentioned above, was boycotting the Security Council sessions. As noted in Allan Millett and Peter Maslowski For the Common Defense (1994), the UN meant to restore the 38th parallel as the border between North and South Korea, which would perform the idea of containment of communism.

Truman ultimately asked for and got congressional sanction for supplemental defense finances, draft expansions, and wartime powers for himself. Congress and the Americans supported the president’s aim of halting communist hostility. The Gallup poll in July 1950 showed 66 percent approved the result to send American troops to stop the North Koreans. John Mueller War, Presidents and Public Opinion (1973) and his articles, particularly “Trends in Popular Support for the Wars in Korea and Vietnam” (1971), reveal that Truman rode the wave of overpowering popular support into the fall of that year. With UN troops approaching the communist forces north to the border of China, many Americans saw a chance to unite all of Korea under “democratic” leadership. Despite a few Chinese border incursions in late October, General Douglas MacArthur’s mid-November promise to have the troops home by Christmas strengthened Truman’s hand. According to Mueller, as long as the public believes the war will be successful but short, public support remains high.

The Korean war itself was mainly a predictable conflict. Nuclear weapons, which displayed so dominantly in those late 1940s’ “War Tomorrow” scenarios, both official and popular, were, of course, not engaged. Very few “push-button” weapons were arranged. (Senator Brian McMahon remarked at the time that “We don’t even have the push-buttons for push-button war!”) In fact, the irresistible bulk of the arms employed in Korea were not only traditional on both sides, but most of the weapons were the lefts from the Second World War. The American GI was issued the same fine M-1 Garand semi-automatic rifle that his older brother or father had drawn in the Second World War. There were no “Flying Wings” or even the more conventional B-36 intercontinental heavy nuclear bombers over Korea. Rather, B-29s, the same bombers that had burned the heart out of Japan’s cities five or six years earlier, torched Pyongyang and Sinuiju in incendiary raids that would have been thoroughly familiar to any bombardier from the Tokyo fire raids. Even the uniforms on both sides (except for the North Koreans) were identical to those of Second World War belligerents, if not actual surplus stock. In fact, the only major new military equipment items were the latest jet fighters employed by the contending forces over “MiG Alley”, the 3.5in anti-armor “bazooka”, the 75mm recoilless rifle, some post-war model tanks — and the US armored combat vest.

This war did not just look back to the Second World War. By the summer of 1951, the fighting had hardened into a stalemate with trench lines, night raids, heavy bombardments, and limited offensives that won limited terrain. It all was in many ways reminiscent of the Western Front of the First World War.

Both the US Army and the CPV had their lessons to learn in this war, particularly those involving the power of mass attack by under-armed armies n the face of enemy firepower and the courage and quality of their opponents. It is a tribute to both armies that they came out of the Korean War as considerably better forces than when they went in.

The war rested much more easily on the United States than on China or the two Koreas, for as in both World Wars, the American homeland was spared physical ravages. This situation likely explains why Americans seemed more willing to consider the strategic bombing of civilian targets, or even to use nuclear weapons. Europeans, who had themselves been the victims of heavy city bombing in the Second World War, pointed out that most of them were under the Soviet flight path to the West.

Conclusion

Few wars in modern history have concluded with such an even distribution of gains and losses as the Korean War. The Republic of Korea and the UN side could take satisfaction in having driven the invader from most of the territory of the ROK while the Communists could rejoice that the UNC forces had been almost completely expelled from the DPRK. The armistice line itself pushed north into the former DPRK in the east, but down into previously ROK territory in the west. Both sides had initially fought for total victory and the actual destruction of their enemy’s government; both sides by 1951 had reluctantly come to accept the military fact that total victory would of necessity involve a considerably greater war than either the Chinese or the UN coalition were willing to fight. Significantly, both the governments of the ROK and the DPRK held out the longest for complete victory—and unification of Korea. And both were overruled by their more powerful allies.

References

- Bernstein, Barton J. “Syngman Rhee: the Pawn as Rook the Struggle to End the Korean War.” Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars 10.1 (1978): 38-50.

- Boose, Donald W. “Rethinking the Korean War.” Parameters 33.4 (2003): 175

- Brune, Lester H., and Robin Higham, eds. The Korean War Handbook of the Literature and Research. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1996.

- Halliday, Jon. “What Happened in Korea? Rethinking Korean History 1945-1953.” Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars 5.3 (1973): 36-45.

- Kaufman, Burton I. The Korean Conflict. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1999.

- Millett, Allan R. The Korean War. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2000.

- Pierpaoli, Paul G. Truman and Korea: The Political Culture of the Early Cold War. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1999.

- Sandler, Stanley. The Korean War: No Victors, No Vanquished. London: UCL Press, 1999.

- Stueck, William. Rethinking the Korean War: A New Diplomatic and Strategic History. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002.

- Wikipedia, 2007 Korean War. Web.