The collapse of the financial systems of Thailand, Philippines, Indonesia, and Malaysia has its roots in the fundamental and structural foundation of the international capitalist system which unavoidably will contribute to its crushing, under its own weight (Rahman, 1997).

“The financial crisis was transformed into a full-blown recession or depression, with forecasts of GNP growth and unemployment becoming more gloomy for affected countries” (Khor, n.d.). “The threat of depreciation spread from a few countries to many in the region, and also to other areas such as Russia, South Africa, and possibly Eastern Europe and South America” (Khor, n.d.).

The Potential Causes of the Financial Crises

As far as the causes of the financial crises in these countries concerned there is no single opinion. They vary from economy to economy. The Asian Tiger economies were growing and were open to foreign investments, goods and services, capital flows and relying heavily on dollar markets (Nanto, 1998).

“There has been a great debate over the causes of this depreciation as weather the domestic policies and practices or the inherent and unstable nature of the global financial system were responsible for it” (Garay, 2003).

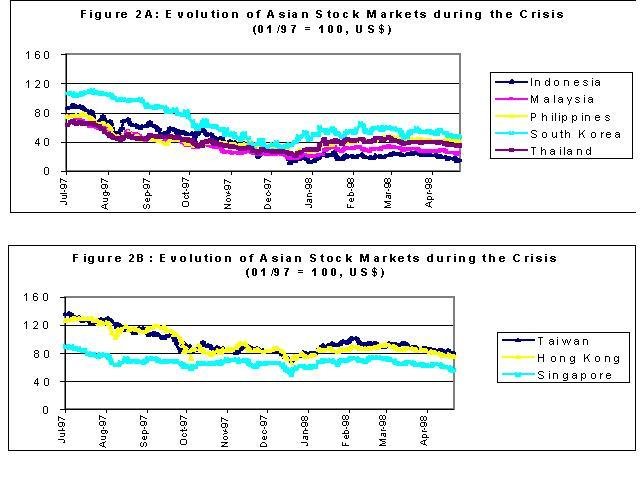

In the first phase of the crisis , the international establishment (represented by the IMF) and the G7 countries placed the blame directly on domestic ills in the East Asian countries as it spread from Thailand to Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, then to South Korea (Garay, 2003).

But soon another view emerged which put the blame on the developments of the global financial system: the combination of financial deregulation and liberalization across the world; the increasing interconnection of markets and speed of transactions through computer technology and the development of large institutional financial players” (Garay, 2003).

“A developing country opens itself to the possibility of tremendous shocks and instability associated with inflows and outflows of funds when it carries out financial liberalization before its institutions or knowledge base is prepared to deal with the consequences” (Garay, 2003).

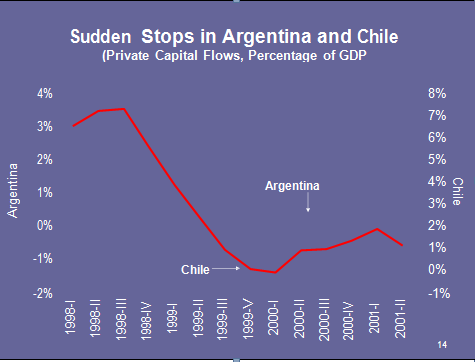

“A total of US$184 billion entered developing Asian countries as net private capital flows in 1994-96, according to the Bank of International Settlements” (Garay, 2003). “In 1996, US$94 billion entered and in the first half of 1997 $70 billion poured in” (Garay, 2003). “With the beginning of the crisis, $102 billion went out in the second half of 1997” (Garay, 2003).

“From the above mentioned figure it is evident that the flows (in and out) can be so huge; the shifts can be so unpredictable and sudden when inflow turns to outflow and the huge capital flows can be subjected to the tremendous effect of “herd instinct,” in which a market opinion or operational leader starts to pull out, and followed by a panic withdrawal by large institutional investors and players” (Garay, 2003).

To maintain foreign investors’ confidence transparency on the business and government level is highly required. In the absence of transparency on such key economic variables as foreign reserves and policy directions, herd instinct prevails, which can make the situation uncontrollable (Kihwan, 2006).

“In the case of East Asia, although some of the currencies were over-valued, there was an over- reaction of the market, and consequently an ‘over-shooting’ downwards of these currencies” (Garay, 2003). “It was a case of self-fulfilling prophecy. The financial speculators, led by some hedge funds, were also responsible for the original ‘trigger action’ in Thailand.

The Thai government used up over US$20 billion of foreign reserves to fight off speculative attacks” (Garay, 2003). “Speculators borrowed and sold Thai baht, receiving US dollars in exchange” (Garay, 2003). “With the falling of the baht, much less dollars were needed to repay the baht loans which made large profits for them” (Garay, 2003).

“According to a report in Business Week in August 1997, speculative attacks on Southeast Asian currencies in July 1997 contributed to big profits for the hedge funds.

According to Business Week, in July (the month when the Thai baht went into crisis and when other currencies began to come under attack) As a whole, the hedge funds made only 10.3 percent net profits (after fees) on average for the period January to June 1997whereas their average profit rate jumped to 19.1 percent for January-July 1997.

Therefore, the addition of a single month (July) made the profit rate so far this year to almost double” (Khor, n.d.). “In some countries, the depreciation in the currencies was due to the outflow of capital by foreigners as well as local people who feared further depreciation, who were concerned about the safety of financial institutions” (Khor, n.d.).

The East Asian financial crises are considered to be the result of over-investment on the part of the bankers and businessmen within the region as well as by the international bankers and businessmen. The market participants argue that “there was too much money chasing too small an investment outlet” (Rude, 1998).

Surplus money was flowing into Korea and Southeast Asia to be profitably placed. The potential causes of the Southeast Asian financial crises can be distinguished between long-term secular developments, the medium-term economic conjuncture, and any immediate (efficient) cause (Rude, 1998).

The market participants advocate that a decline in the profitability and a rise in the riskiness of the underlying investment projects, a deterioration of local balance sheets, and a rise in the magnitude of the foreign exposures were the relevant long-term developments and that these trends created a financial structure that made a financial crisis in East Asia both possible and unavoidable.

Changes in the economic conjuncture in 1996 and early 1997 pushed what was both possible and inevitable toward becoming a reality. The exchange rate attacks that began mid-1997 were the immediate trigger. From this perspective, deterioration of the underlying economic fundamentals and financial panic caused the crisis (Rude, 1998).

The low-wage, export-oriented, foreign-financed growth strategy that the countries in Southeast Asia and the Republic of Korea were following ahead of the crisis became the victim of its own success. The underlying investment projects that both local and foreign capital were financing in the region were profitable and productive at one time.

But because of the additional productive capacity created in one country after another in the same or similar industries, problems like rise in wages, decline in profit margins in the export industries, and the flow of funds toward the non-traded goods sector and into more speculative activities in the local real estate and equity markets were mushrooming (Rude, 1998).

On the other hand, the relevant cash flows were becoming increasingly problematic, leading to a gradual deterioration in the balance sheets of local financial and non-financial institutions: increase in the liabilities to foreign and local creditors, decrease in the asset quality, rise in the leverage ratios.

The gap- and duration-related interest rate exposures were escalating due to an increase in the maturity mismatch of assets and liabilities. Meanwhile, foreign capital continued to flow into South East Asia and the Republic of Korea from Europe, the United States, and Japan.

An accommodating monetary stance and low inflation, contributed to low interest rates in the major industrial countries. The rise in the equity prices in the United States and Europe appealed investors to find sizeable exposures in highly valued, if not over-valued, securities in companies in the industrialized nations whose earnings potential may have fallen below those available in the Pacific Basin emerging markets.

Compelled by a competitive search for higher yields to take on the Republic of Korea’s and Southeast Asia’s greater credit and country risks, international creditors increased their exposures to local banks and corporations, both directly through loans and indirectly through local and international bond markets.

Japanese lenders were particularly eager to extend credits to the region, due to the poor investment prospects at home, especially to the foreign branches and subsidiaries of Japanese corporations. Equity investors in the United States and Europe were also driven to increase their exposure to the region’s greater market risks, both for diversification purposes and to search for even higher capital gains (Rude, 1998).

Once profitable and productive these foreign investments, like the domestic ones, took on an increasingly speculative tone, their asset quality declined, the associated leverage ratios and interest rate risks increased, and the maturities were shortened. The aggregate market exposures became increasingly complex and obscure as well (Rude, 1998).

It can be illustrated evidently by the two notorious off-balance sheet/derivative strategies used in East Asia. Special purpose vehicles (SPV) were set up to direct fund into the region and particularly into the Republic of Korea by the U.S. banks.

In these arrangements, some of the stock was transferred by the banks to the SPVs which in turn issued short-term paper in the international markets using that stock as security and used it to make investments that were considered advisable by the banks. In reality, the banks had assumed a foreign exposure, but it never showed up on their balance sheets (Rude, 1998).

“Total Return Swap” (or TRS) was another strategy in the same direction. These were a series of triangular transactions between international investment banks, Korean banks, and Indonesian companies. Double swaps were set up between the Indonesian companies and the investment banks, on the one hand, and between these banks and the Korean banks, on the other.

Under these arrangements, the Indonesians, who did not have the Korean’s high credit ratings, were able to borrow, and the Korean and investment bankers made a high rate of return. The setback was that the Korean banks had to compensate the investment banks for any losses if the Indonesian companies went bankrupt, which ultimately happened (Rude, 1998).

Three major changes in the economic conjuncture took place in 1996 and early 1997. First, due to developments in the general international economic environment and other factors, export growth rates, and hence, domestic growth rates in the region began to slip.

Second, Official interest rate increases in the United States (March, 1997) and Germany (October, 1997) proposed that lending in the less risky Western industrial countries would become more profitable.

Third, the economic and financial situation in Japan worsened. Japanese bankers and institutional investors began to consolidate their exposures not only at home, but in the Republic of Korea and Southeast Asia as well as Japan’s banking problems began to intensify (Rude, 1998).

Local and foreign investors in the East Asian emerging markets were now reluctant to extend further credits and other moneys and soon began searching for ways to actually lessen their exposures (Rude, 1998).

So, the extent and depth of the crisis should not be attributed to deterioration in fundamentals, but rather to panic on the part of domestic and international investors (Zhuang & Dowling, 2002).

In doing so, local and foreign market participants found that they now had a foreign exchange exposure that had in fact not existed before. Now, suddenly that the outlook had changed and a rush for the exit had ensued, the pressure on the local currencies was only downward.

While it is simplistic to say that the fixed exchange rate regimes were to blame for the crisis, investors’ foreign exchange exposures had become the weakest link in the entire investment chain, and successive runs on the local currencies would be the mechanisms that would finally bring the whole, already precarious, financial structure down ((Rude, 1998).)

The financial crisis in East Asia is a historic event. It has shocked the world economy profoundly. The crisis may have brought the process of globalization and internationalization to an end, which has been the characteristic of international economic developments since the early 1980s.

It is necessary to limit the shriveling effects of the crises immediately. Then there is an urgent need to tackle the question of globalization and liberalization: if there is a need for a new architecture for the world economy, and if so, what shape it should take (Rude, 1998).

“The crisis brought about macro-level effects, counting sharp reductions in values of currencies, stock markets, and other asset prices of several Asian countries” (Hwang, 2009). “Many businesses collapsed, and as a consequence, millions of people fell below the poverty line in 1997-1998.The most affected countries by the crisis were Indonesia, South Korea and Thailand” (Hwang, 2009).

Argentina Crisis

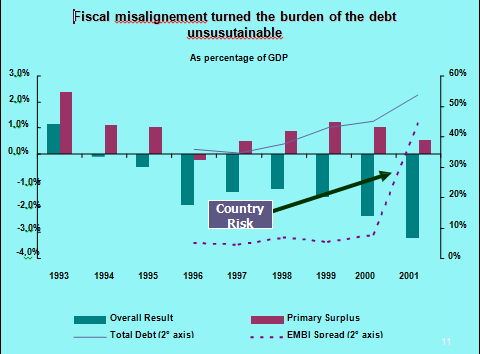

The Argentina crisis of 2001-2002 is the example of the social, economic and political turmoil. During the time of 1990’s Argentina had a very successful economy due to lower inflation rates, Argentina became the favorite point for international financial lending that was strictly following the IMF regulations (Argentina Economic Crisis of 2001, n.d.). The export of beef and grain made Argentina’s economy very stronger (Tonelson, 2002).

But, suddenly, in 2001 the Argentine economy suffered a terrible loss. The government was not in a position to pay foreign debts and a bid amount of dollars in government spending were cut short (Argentina Economic Crisis of 2001, n.d.). A news published in BBC says, “Many in Argentina blame the IMF for their country’s economic collapse in 2001 and 2002” (Argentine Financial Crisis, n.d.).

The Argentina Crisis was Currency and Bank crisis. It was also due to wrong response to globalization (Ferrer, 2001). Feldstein (2002), “for example, argues that the crisis was due to exchange rate overvaluation that could not be easily corrected and to an excessive amount of foreign debt” (Torre et al, 2002, p.1).

Actually, if we review the history of Argentina economy, we will find that in 1913 the actual GDP per person in Argentina was almost 72 percent which was same as the US had and it was higher than the countries like Germany, France and Sweden.

In 1950 though GDP became 52 percent but it maintained the same level same like US and higher than Germany but a drastic slack came in 1990s when its GDP came down by 28 percent and Argentina became far behind other Western European countries. It did not happen that Argentina became a poor country but its economy’s growth stopped for a while and gave unsatisfactory results (Saxton, 2003).

Then the efforts came from the President Memen and he tried to adopt a free market approach. It helped in lessening the burden of the government by doing privatization, cutting tax rates and doing some reformations in the state. President Memen took quick actions to imply the reformations despite of much opposition. He did not adopt any slower or normal process for passing laws through Argentina Congress (Saxton, 2003).

Now the actual crisis in Argentina’s economy started during the period of recession and when Fernando De la Rua became the president in 1999. At the time of his presidency he committed to finish the recession and to remove corruption (Saxton, 2003).

President De la Rua got the approval of increasing three higher taxes which had to be effective from April, 2000 to August 2001.

“The increases came on top of already high tax rates. The highest rate of personal income tax, 35 percent, was near the level of the United States, but the combined rate of federal payroll tax paid by employer and employee was 32.9 percent, versus 15.3 percent in the United States; the standard rate of value-added tax was 21 percent, versus state sales taxes of 0 to 11 percent in the United States; and Argentina imposed taxes on exports and (from April 2001) on financial transactions, taxes that do not exist the United States.

Argentina’s high tax rates encourage tax evasion: an estimated 23 percent of the economy is underground and 30 to 50 percent of all transactions evade taxes” (Saxton, 2003, p.10).

The economy started falling down in 2000 and it became slower than 1999. Richard Lopez Murphy, the new Minister of economy at that time promised to fortify the economy of Argentina by reducing spending of about 4.5 billion pesos with-in two years that was actually 1 percent of GDP per year that aroused the anger of public as these cuts were profounder than any other Argentinian government and this caused Lopez’s resignation with-in two weeks from his post joining (Saxton, 2003).

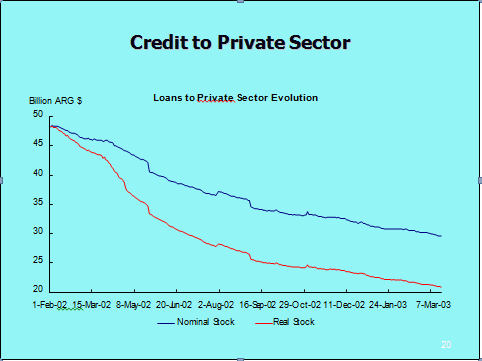

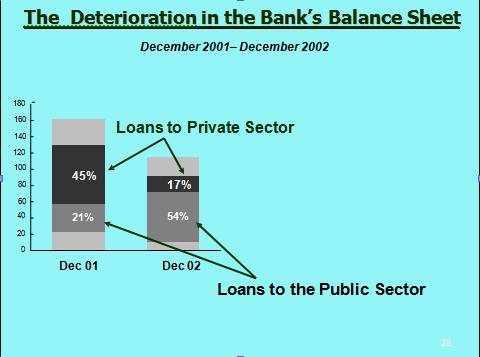

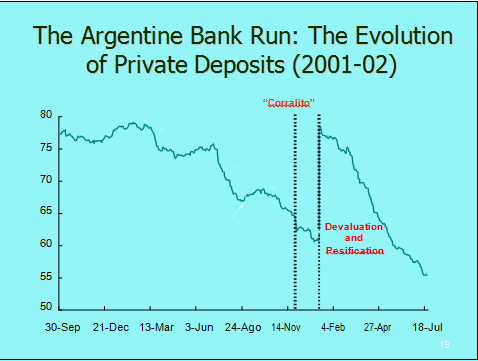

Turmoil occurred in December 2001 when bank deposits were freeze due to a large number of withdrawals on November 30th. The people became depressed as they were not able to make payments. Credit got disappeared so people started showing their anger by doing demonstration in streets.

In December, the IMF declared that it would not any loans to Argentina as the country was not the state of following loan agreements. Because of this Argentina was not able to get any loan from any foreign source. Again there were lots of protests in the country which forced De la Rua to resign from his post (Saxton, 2003).

President Duhalde took the place of De la Rua as a president and he tried to adopt new economic policies. He tried to reserve the policy like convertibility system. This convertibility system was criticized for many years.

“The dominant view among economic observers inside and outside Argentina was that the peso’s one-to-one exchange rate with the dollar had made the peso overvalued, making Argentine exports uncompetitive and preventing an export-led economic recovery” (Saxton, 2003, p.13).

The government took some actions after following the regulations of Law of Public Emergency and Reform of the Exchange Rate Regime (January 6, 2002). The measures taken by the government are as follow (Saxton, 2003):

- It ended the convertibility system.

- It devalued the peso from the rate 1 per dollar to 1.40 per dollar.

- It converted dollar bank deposits and loans into pesos.

- It seized the dollar reserves of banks.

- It imposed exchange controls.

- It made penalty double for the employers who made employees without a job.

- It introduced lots of new taxes and focused on frequently revising them.

The new policy resulted in some loss like Argentina’s economy became less from 5.5 percent to 10.9 percent in between 2001-2002.the number of bankruptcies became larger. Duhadle’s economic policies created big losses for the foreign banks and utility companies (Saxton, 2003).

Some economic recovery was observed in the period of August 2002. Though it initially was not that strong as it should have been but later it caught strength. The exchange rate became less up to 4 pesos per dollar during 2002 and later in 2003 it became less than that by making it 2.90 pesos (Saxton, 2003).

So Argentina’s crisis was not the failure of free markets rather it was the crisis came from the mistakes of the federal government in implying their economic policies. “Long-term growth will require reversing the policy direction of the last several years and allowing greater economic freedom, anchored in respect for property rights” (Saxton, 2003,p.49)

Reference List

“Argentina Economic Crisis of 2001.” UC Atlas of Global Inequality. Web.

“Argentine Financial Crisis”. Web.

Blejer, M. I. 2006. “Some Lessons From the Recent Financial Crisis in Argentina (2001/2).” Seminar on Crisis Prevention in Emerging Markets Singapore. Web.

Ferrer, A. 2001. “The Argentine Financial Crisis. World Press Review Online”. Web.

Garay, U. 2003. “The Asian Financial Crisis of 1997 – 1998 and the Behavior of Asian Stock Markets”. Web.

Hwang, J. 2009. “Background: 1997 East Asian Financial Crisis. Life”. Web.

Kihwan, K. 2006. “The 1997-98 Korean Financial Crisis: Causes, Policy Response and Lessons”. The High Level Seminar on Crisis Prevention in Emerging Markets. Organised by The International Monetary Fund and The Government of Singapore. Web.

Khor, M. “The Economic Crisis in East Asia: Causes, Effects, Lessons”. Web.

Nanto, D. K. 1998. The 1997-98 Asian Financial Crisis. CRS Report. Web.

Rahman, A. 1997. “The Southeast Asian Financial Crisis and Distributive Justice in the Global System: Dare we cteate a new frame of mind?” Southeast Asian Financial Crisis of 1997: Retrospective essay. Columbia University, New York. Web.

Rude, C. 1998. “The 1997-98 East Asian Financial Crisis: A New York Market- Informed View.” Department of Economic and Social Affairs. in conjunction with the Regional Commission of the United Nations. Web.

Saxton, J. 2003. “Argentina’s Economic Crisis: Causes and Cures”. Joint Economic Committee United States Congress. Web.

Tonelson, A. 2002. “The Real Roots of the Argentine Financial Crisis. American Economic Alert.” Web.

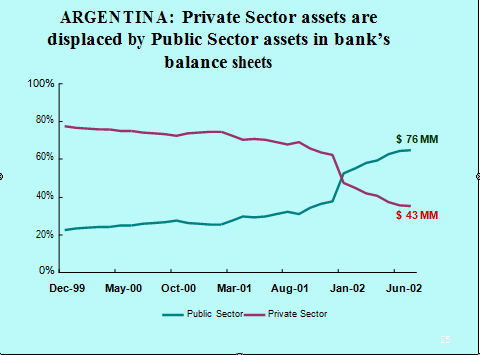

Torre, A. et al. 2002. “Argentina’s Financial Crisis: Floating Money, Sinking Banking”. Web.

Zhuang, J. & Dowling, J. M. 2002. “Causes of the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis: What Can An Early Warning System Model Tell Us?” ERD Working Paper No. 26. Economic Research Department. Web.