Introduction

International negotiation in general is an interactive process, which serves as an instrument to end a continuing conflict or to arrive at a solution for a controversy. Good preparation forms the basis for successful international negotiations. “It may also serve as a means to achieve common objectives or agreements among individuals or groups (parties) in relation to a specific object, material or immaterial, within a framework of pre-established rules, known and accepted by the parties involved. These parties are directly or indirectly interested in the object and in the objectives of the negotiation,” (Meridiano, 2010). International negotiations also include international business negotiations, which falls under the scope of this research.

While adequate preparation happens to be the most important aspect that precedes every round of international negotiations, negotiators often are found to be inadequately prepared and there has been dearth of research on the subject. Most of the existing guidelines have been developed over the period without any research backing. These guidelines focus on concepts such as the underlying concerns of a negotiator and the best alternatives to a negotiated agreement (BATNA), and mostly these guidelines are adopted by the negotiators in their encounters (Fisher and Ertel, 1995; Thompson, 1998).

In the realm of international negotiations, the terms planning and preparation are often used interchangeably. However, “preparation” is much more encompassing, as it includes all the efforts and activities of the negotiator undertaken before the actual negotiation takes place, when the negotiator is at the top of his form. Without undertaking an effective preparatory process, the negotiator in an international negotiation is not likely to get satisfying and successful outcomes. Therefore, preparation becomes an essential process in international negotiation. In this context, this presentation focuses on the preparation for international negotiations from a systematic perspective.

International Negotiations

This section reviews the perspectives on international negotiations to have a better understanding on the scope of the research inquiry. The objective of any international negotiation is to arrive at an acceptable conclusion, which reduces disagreements and enhances benefits for the parties to the negotiation. According to Martin et al., (1999), a comprehensible negotiation process forms the basis of any fruitful business association at an international level.

International negotiations for the purpose of this paper are restricted to international business negotiations. An international business negotiation can be defined as the interaction undertaken deliberately among two or more social units. Out of the social units involved in the negotiations, one of them represents a business entity. The parties to the negotiation originate from varied cultural backgrounds and each of them attempt to describe their affiliation to a specific business issue. International negotiations may take place between one company and another or between a company and a government.

The negotiations are interpersonal interactions over any business issue as the negotiation may relate to the conclusion of a sale contract, issue of licenses, entering of joint ventures or acquisition of one entity by another (Weiss, 1993: 270). The process of negotiation involves the stages of pre-negotiation, actual negotiation and post-negotiation. A negotiation becomes successful, when there is a smooth flow of the negotiation process in all the three stages.

“The pre-negotiation stage, which involves the preparation and planning, is the most important step in negotiation,” (Ghauri, 1996:14) and this stage is the central focus of this study. The pre-negotiation stage becomes important since it is the starting point in international negotiations (Lewicki, et al., 1994). Activities like building trust and relationship among the parties and “task-related behaviors” which concentrate on the choices of different alternatives available to arrive at a solution constitute the major interactions during the pre-negotiation stage (Graham & Sano 1989, Simintiras & Thomas 1998). “In brief, the first stage of negotiation emphasizes getting to know each other, identifying the issues, and preparing for the negotiation process” (Numprasertchai & Swierczek, 2006).

“The negotiation stage involves a face-to-face interaction, methods of persuasion, and the use of tactics. At this stage negotiators explore the differences in preferences and expectations related to developing an agreement,” (Numprasertchai & Swierczek, 2006). The post-negotiation stage involves exploring concessions, looking into compromises, evaluation of the agreement and follow up through documentation or other procedures.

In most international negotiations, these three phases are undertaken at the same time. “The negotiation process is a dynamic process, involving a variety of factors related to potential negotiation outcomes,” (Numprasertchai & Swierczek, 2006).

There is an element of complexity in international negotiations, since such negotiations take place between persons belonging to different cultures. “International business negotiations are typically more complicated and difficult to assess than the negotiations taking place between negotiators from the same culture,” (Numprasertchai & Swierczek, 2006). The reason for the difficulty is due to the differences in the values that the negotiators hold.

Negotiations are carried out based on various approaches developed on the exclusive standpoints of the negotiators concerned. “Other external influences such as international law, exchange rates, and economic growth also increase the complexity of negotiations,” (Numprasertchai & Swierczek, 2006). It is essential that the international negotiators understand the values of each party so that they may be able to amend their negotiating approaches and styles to meet the emerging situations and arrive at an amicable solution to the business issue.

Preparation for Negotiation – an Overview

The first rule underlying effective negotiation is to get prepared for negotiating. In general, there are three different activities involved in the process of preparing for a negotiation. They are

- information gathering,

- analysis,

- planning.

In the practical handbooks outlining negotiation practices as well as other analytical papers, these three activities have been regarded as the most important tasks that a negotiator must undertake to ensure successful outcomes from any negotiation. Some of the authors argue that the preparation for negotiation will be better able to give an upper hand to a negotiator than any other activity in the process of negotiation.

This implies that those who prepare best will be able to negotiate the best. Nevertheless, in the negotiation literature there are few research findings about how much one should prepare. This situation gives an impression that one can never be too prepared for negotiating except that more preparation will yield better outcomes from the negotiation. Given the central role in the negotiation process there is no inclusive definition of the term “preparation” found in the literature, nor is there an analysis of its boundaries and limits and characterization of the preparation process as a whole.

Traditional View of Preparation

A number of activities have been identified which a negotiator has to undertake after the decision to negotiate has been taken, but before arriving at the negotiating table. These activities cover gathering information on the issue to be negotiated and information on the participants in the negotiation. The activities also include analysis of one’s own interests and preferences of the negotiator, as well as the parties on the other side, and planning the course of action, when the actual process of negotiation begins and face-to-face interaction takes place (Breslin and Rubin 1991; Fisher and Ury 1991; Johnson 1993; Keeney and Raiffa 1992, Lax and Sebenius 1986, Lewicki et al 1994, and Raiffa 1992). These activities can be grouped into three distinct categories such as

- information gathering,

- analysis,

- planning.

Collecting Information about Parties and Issues

This can be taken as the first step in the process of preparation for a negotiation, where the activities of data collection and research into the history of the issues to be resolved are undertaken. This step involves studying the precedents for resolving similar issues, receiving consultation from external experts and interviewing those people who have negotiated with the other party in the past instances (Lewicki et al 1994). Raiffa (1992) includes all those activities in this group, where the negotiator can learn whatever is possible about the trustworthiness, ethics, style and personality of the other party to the negotiation.

Analysis of Preferences, Interests and Alternatives

According to Fisher and Ury (1991), a negotiator has to understand his own interests, and he should be able to distinguish interests from positions. This line of analysis is extended by Lax and Sebenius (1986), to separate interests in outcomes of the negotiation, from the interests of the parties in the relationship among them currently and in the future. According to Fisher et al., (1994), it is essential that the negotiator understand the interests, values and perceptions of the other parties to the negotiation, and based on the understanding the negotiator has to generate options that the other party is most likely to accept. Keeney and Raiffa (1992) and Raiffa and Sebenius (1993), based on multiattribute utility theory have developed a methodology “for quantifying interests, scoring and ranking preferences and evaluating tradeoffs among issues and outcomes” (Watkins & Rosen, 2001).

Negotiation Planning

In most of the cases, it is observed that the negotiators attend negotiation without adequate preparation based on the inherent belief that negotiation is an intuitive process and any emerging situation can be met with the experience and exposure to different situations. Conversely, when the negotiators are able to adequately plan ahead of actual negotiation, taking the negotiation as a process and campaign they are sure to come out with breakthrough results. Negotiation does not constitute a single and conclusive event but is a process consisting of a series of proposals and counter proposals made by the parties seeking to arrive at an equitable balance among them.

This section elaborates on negotiation planning which is a part of the preparation for international negotiation. Although authors like Lewicki et al (1994), use the term “planning” to denote the entire process of preparation for negotiation, this section deals with planning to identify a narrower set of activities, which are undertaken by the negotiator to decide on the course of action to be pursued at the negotiating table.

Planning includes the creation of an action plan. “The negotiation literature gives considerable attention to such tasks as generating options and combining them into packages or proposals (Raiffa and Sebenius 1993), anticipating the actions of the other side, envisioning possible responses, and planning for contingencies.” Lewicki and Litterer (1985) have identified three different types of planning activities –

- strategic planning,

- tactical planning,

- administrative planning.

Setting long-term goals and identifying the ways of meeting these long-term goals is the focus of strategic planning. Tactical planning aims at developing specific short-term steps designed to achieve the long-term goals established through strategic planning. “Finally, administrative planning is the process of making logistical and allocative arrangements for the negotiation: assigning roles to team members, choosing locations for meetings, and clarifying lines of communication and authority” (Watkins & Rosen, 2001).

Negotiation planning is the systematic mapping of the different steps involved in the process of negotiation with the other party. “Negotiation Planning is not a stand-alone activity; it occurs within a process context and a variety of cultural variables and involves ongoing external and internal conditioning,” (Seacchitti & Guertin, 2005). The cultural variables affect the manner in which the plans and actions are proposed and developed. Irrespective of the influence of the cultural and other variables acting on the process, planning is an essential step in the process of negotiation and is often overlooked.

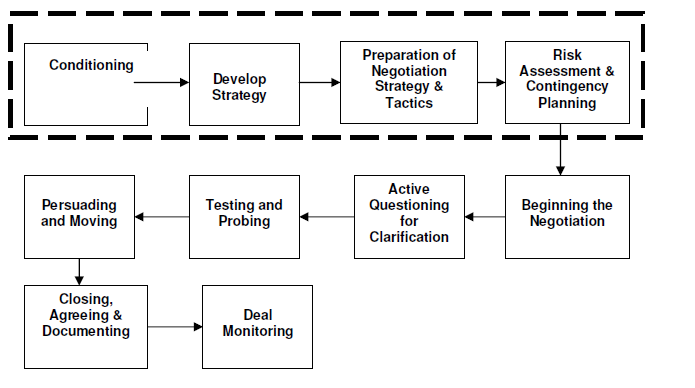

The above diagram illustrates the overall process of negotiation in general, which also applies to international negotiations. The first four steps encircled within bracketed areas reflect the important steps in the planning process. These elements are vital in nature and actions in these areas need to be undertaken at the phase preceding the actual negotiation. These steps also form part of the preparatory phase of the negotiating process. Preparation of negotiation strategies and tactics take place before the negotiation takes place.

In the process of negotiation, conditioning calls for placing a starting point in the minds of the opponents and this starting point is close to the end result, the negotiator is expected o achieve. Planning involves the consideration of the concerns relating to the objectives to be achieved, the opponents in the negotiation and the ways in which an agreement can be reached. In cases of international negotiations, the negotiators often tend to be concerned with cultural factors.

However, in most instances, the negotiators either underestimate or overestimate the influence of cultural factors on the negotiation process. The reason for such wrong estimation is that they consider the cultural factors without regard to the non-cultural factors or sometimes only in association with behavioral factors. They do not consider the cognitive or value-oriented effects of cultural factors on the negotiation process (Watkins & Rosen, 2001).

Problem Statement

In any international negotiation, the objective of the negotiators is to reach an optimal solution so that maximum gains occur to their sides. One of the vital factors for making a fruitful negotiation is to evolve a comprehensive negotiation approach. This calls for a undergoing an elaborate preparatory process so that the negotiator will be able to collect information, analyze it and make proper planning for successful negotiation.

Since the preparation process preceding the actual negotiation can ensure outstanding results, the study of the preparation approach becomes important. There are no well-defined procedures outlining the preparation process and this necessitates a relook into the preparation process for negotiation. Negotiations done with an “off the cuff” approach do not yield spectacular results, making the application of a preparatory approach not only significant but absolutely important for ensuring great success in negotiations.

Preparation for negotiation makes a key difference in the approaches of skilled and amateur negotiators and often determines the course of negotiations changing the outcomes. In addition, the negotiators, before entering the negotiation table, must have a better understanding of the situation and the range of acceptable and unacceptable solutions to the issue. The negotiator can improve such understanding and acquire self-confidence, only when a thorough preparation to negotiation is undertaken.

Aims and Objectives

The central focus of this research is to make an in-depth study of the preparation process for international negotiations. In achieving this aim, the research attempts to accomplish the following objectives.

- To study the international negotiation process in general to understand the role and importance of the process of preparation in negotiation.

- To recognize the limitations associated with traditional models of negotiation preparation process.

- To understand the relationship between the process of learning and planning in international negotiation process.

- To consider different approaches to preparation processes as practiced by negotiators from different regions/settings.

Research Methodology

This study follows a descriptive and exploratory qualitative case study for achieving the objectives of the research. In recent years, the roles of descriptive and qualitative research methodologies, which include case studies, participant observation, informant and respondent interviewing and document analysis have been emphasized and pursued (Scapens, 1990). In these approaches, the researcher is required to have closer involvement with the organizations or issues under study. Based on detailed examination of the institutions or organizations concerned, research findings are described instead of being prescribed.

One qualitative method, which seems to offer at least partial solution to the currently unsatisfactory research, is the case study approach. In contrast to simplistic and superficial findings of the quantitative method in some instances, case study provides the opportunity for the research to develop better theories in management and accounting control systems, which are based on real world managerial practices. In addition, a case study allows flexibility in the interpretation of the findings. The researcher for example, is not restricted to his/her original theory, but most often is encouraged to come up with new theoretical discoveries.

Case study has been used as a research tool by a number of researchers. “Case study is an ideal methodology when a holistic, in-depth investigation is needed” (Feagin et al. 1991). Different exploratory studies in the discipline of social studies have made use of the case study method for collecting relatable information about the topics researched. Following a case study as the research tool allows the researcher to follow well -developed techniques to meet the requirements of data collection for any kind of investigation. “Whether the study is experimental or quasi-experimental, the data collection and analysis methods are known to hide some details,” (Stake, 1995).

However, the case study method has the unique capability of retrieving additional information from different perspectives using multiple sources of data. There are varying kinds of case studies, which can be engaged for conducting studies in different settings. These are exploratory case studies, explanatory case studies and descriptive case studies. This research will use an exploratory case study method to analyze the preparatory process of international negotiations carried out by the negotiators belonging to China and will present an analysis of the negotiating process including preparation.

Structure of the Report

In order to make a comprehensive presentation this research report is structured to have the following chapters.

Introduction

The introductory chapter briefly described the background and scope of the research on preparatory approach to international negotiations. The chapter presented an overview of the preparation process and laid down the research objectives.

Literature Review

The second chapter reviews previous literature and research findings in preparation for the international negotiation process. The review addresses the underlying assumptions, problems in understanding of preparation and a rethinking of preparation.

Analysis

This chapter presents an analysis of the preparatory process in international business negotiations in the country of China.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The chapter summarises the research process and findings and make a few recommendations for future research studies.

Literature Review

International negotiation is the association between planning for international transactions and implementation of such planning. The ability to negotiate successfully depends largely on the efforts the parties put into the preparation for such international negotiation. The central objective of this research is to gain a better understanding of the preparatory approach to international negotiation, by exploring and describing the process of preparation.

The objective becomes significant in view of the fact that international marketers are becoming business negotiators engaged in continuous cross-border transactions with a number of different people ranging from consumers to competitors. Ghauri and Usunier (1996) argue that people entering into international negotiations will be able to enhance their ability to interact effectively with their foreign counterparts, when they are able to make the necessary adjustments to the cultural backgrounds that they come across during negotiations. The negotiation stage is the connecting link between planning and implementation in the management of international transactions (Deresky, 1996).

Negotiation can be defined as “a voluntary process of give and take where both parties modify their offers and expectations in order to come closer to each other” (Ghauri and Usunier 1996). Each international transaction has a negotiation aspect and every negotiation gives rise to challenges and opportunities to the people who are involved in the transactions.

Especially business negotiations are considered special as the negotiation in this case is purely voluntary and the parties have the option of quitting the process at any time on their own accord. Many growing companies find international negotiations a routine affair and when these organizations operate across geographical borders different cultures often tend to magnify the challenges of negotiation (Herbig and Gulbro, 1996). In this context, this review deals with the preparatory approach for international negotiations.

International Business Negotiations

Any international business involves the participation of parties belonging to two or more countries and it involves the movement of merchandise and service across geographical borders. In general, international business encompasses the field of international trade and commerce and international investments by parties from one country in the assets of another. Tsai (2003) defines international business to include the transfer of goods, which is tangible business or services, which are intangible merchandise between parties belonging to two countries. The term “goods” cover a wide range of commodities including raw materials, semi-finished goods and finished inventory. Similarly, the term “services” covers a number of activities including accounting, transportation, banking and insurance.

Loth & Parks (2002) argues that the term also includes the supply of intangible capital such as trademarks and patents and technical knowhow from one country to another. International investments in general denote the foreign direct investments that parties make in other countries. Apart from including buying of shares and securities, the term international investments include the provision of financial services to foreign owners (Weigel, Gregory & Wagle, 1997; Bergsten & Noland, 1993). The process of international investment incorporates the transfer of productive domestic technology and management from transnational companies to domestic companies (Kaminski, 1999; Bergsten & Noland, 1993).

In pursuing both international business as well as investments, managers increasingly engage themselves in the process of international business negotiations. Gilsdorf (1997) observes that international negotiation is one of the toughest jobs in businesses. Managers usually spend more than half of their time in negotiating (Adler, 1997). International negotiations involve higher stakes than the domestic business negotiations (Mintu-Wimsatt and Calantone, 1991).

Tung (1988) argues that although the parties to international business negotiations intend to reach successful agreements, there is an alarmingly higher level of failure in international negotiations. “The consequences of failure in international negotiations are also high, including limitations on the scope and profit potential of companies, significant increases in non-recoverable expenses, and, perhaps most importantly, decreases in the motivation of the international negotiators.”

There is the need for increased skill and competencies in conducting international negotiations as compared to domestic business negotiations. Several researchers have observed the existence of an extensive literature base covering domestic business negotiations (e.g. Eppler et al., 1998; Perdue, 1992; Sujan et al., 1988; Thomson, 1990). Simintiras and Thomas, (1998) are of the opinion that the international business negotiations literature is normative in nature and it is highly disjointed. However, these views have to be taken as expressed with an extensive review of the international business negotiations literature.

In these kinds of transactions, whenever two parties start negotiating, the complete process of negotiation takes place within the context of the environment under which the negotiation is undertaken and the immediate context under which the parties negotiate with each other. “The environmental context refers to forces in the environment that are beyond the control of either party involved in the negotiations. The immediate context includes such aspects as the relative power of the negotiators and the nature of their interdependence factors over which the negotiators have influence and some measure of control,” (Phatak and Habib, 1996). Both the environmental context and immediate context influence the process and outcome of the negotiations.

The Environmental Context of International Negotiations

There are different dimensions to the environmental context of international business negotiations. They include

- legal pluralism,

- political pluralism,

- currency fluctuations and foreign exchange fluctuations,

- foreign government controls and bureaucracy,

- influence of external stakeholders (Phatak and Habib, 1996).

Legal Pluralism

“The principle of national sovereignty gives every nation-state the right to make laws that are supposedly in its national interests. An international business transactions must comply with the laws of the countries involved,” (Phatak and Habib, 1996). There are certain restrictions imposed by the laws of countries on entering into certain types of transactions. In many countries, there may be sectors such as telecommunications and automobile production, which may not be exposed to one hundred percent foreign investments. For instance, in countries like India and China, foreign enterprises can enter into such sectors only through forming a joint-venture arrangement with some of the domestic companies.

The joint-venture arrangement has an influence on the negotiations among the parties on several major factors such as management and control of the enterprise and international sales provisions. Apart from these, there are the legal obligations on both the sides, which have to be considered in concluding the joint venture arrangements. In such cases, it becomes important that the negotiators fully understand the implications of the currency of the laws in the country with which they would like to have business transactions. It is also important that the persons involved in negotiations refrain from taking any illegal actions prohibited by the laws of the countries involved. “Negotiators should be forewarned about the legal traps that could transform a supposedly good agreement into a nightmare if the legal implications of the transaction are not carefully examined,” (Phatak and Habib, 1996).

Political Pluralism

Each country in the world has its own political system and foreign policy, which determines its trade relations with other countries. International business negotiations are sometimes impeded in the conflicting foreign policies of the two countries. Foreign policies followed by the host county affect the international business negotiations. It therefore becomes important for the negotiators to understand the implications and constraints imposed by the foreign policies of the countries in international business negotiations, as these policies will have direct or indirect impacts on the outcomes of the negotiations. The negotiators should study the potential political fallout of an international business deal before the deal is negotiated and the agreement signed.

Currency Fluctuations and Foreign Exchange

Since international business transactions take place in an environment where multiple currencies interact with each other, the daily fluctuations in foreign exchange value can have a large impact on international business negotiations.

“A business deal that is not effectively structured to compensate and protect against foreign exchange fluctuations is likely to be a prelude to a disaster if the underlying currencies in which payments are to be received precipitously decline in value–or a windfall if they appreciate in value–against the recipient company’s home currency or other stable currencies,” (Phatak and Habib, 1996).

Therefore, it becomes essential that the negotiators for both companies obtain realistic and “most likely” exchange rates for the relevant currencies from international banks or currency future markets before arriving at any resolution based on the currency exchange rates. It is advisable that the negotiators include contingency clauses in the agreements, which would protect both sides from any unexpected fluctuations in currency exchange rates in future.

Foreign exchange control policies of different governments also have an influence on international business negotiations. Exchange control policies affect the import and payment of raw materials and repatriation of profits from one country to another. Therefore, negotiators from a foreign company should ensure that the contracts negotiated and entered into by them provide for the exigencies that might be created by the exchange control policies of the host governments.

Government Controls and Bureaucracy

In the case of certain countries, there will be excessive interference of the government in businesses. “Government agencies may have the authority to control the total output of an industry. Or they may have absolute control over the granting of permits to expand production capacity,” (Phatak and Habib, 1996). A company, which has a potential to increase its market share may be under an obligation to obtain the necessary licenses for expanding capacity, which may be denied many times by the bureaucrats attached to the government. Similarly, a company might need a government license to implement a new strategy in connection with the operation of a new product line. In all those cases where there is a major role played by the government in furthering the business of the company, the negotiations should include the government as one of the parties with whom the foreign firm has to negotiate directly or indirectly.

Influence of External Stakeholders

The external stakeholders are those people who have a direct or indirect interest in the outcome of international negotiations. Examples of external stakeholders include, competitors, customers, labor unions, chambers of commerce and industry and the shareholders of the respective companies. It is important that the negotiators take the interests of most of these external stakeholders if not the interests of all of them into account while drawing up international business agreements, as the stakeholders’ interests are to be protected by any international business negotiations.

Factors influencing Pre-Negotiation

According to Deresky (1996), there are twelve different variables, which influence the process of pre-negotiation and in turn, the preparatory process in any international business negotiations.

They are:

- basic conception of the negotiation process implying whether the international business negotiation follows a competitive process or it depends on the culture of the country. This approach determines the progress of the process of negotiation;

- selection criteria for the members of the negotiating team. There are different attributes to be considered in the selection of the members constituting the negotiation team like experience, status, personal attributes and some other characteristic features. The extent of value involved in the negotiation also determines the selection criteria;

- the significance of the kind of issues involved in negotiation like the price, or the focus on formal and informal relationships;

- the importance of the protocol concerning the importance of procedures and social behaviors;

- the complexity of language implying the extent of reliance placed on verbal and non-verbal cues used to interpret information gathered;

- the nature of persuasive arguments shown by the intention of the parties attempting to influence each other;

- the individuals’ aspirations in the entire process of negotiation – the motivations based on individual, company or community affect the preparatory process to different degrees;

- the feeling of trust and its basis in past experience, intuition or rules and continuance throughout the process of negotiation;

- the propensity to take risk;

- the attitude of each negotiating party towards the time taken for completing the process of negotiation;

- the system of decision-making whether by individual determination or by group consensus;

- the form of satisfactory agreements and whether such agreements are based on trust or the creditability of the parties involved in the negotiating process.

The important point to reckon here is that each of these factors is influenced by the culture of the country. The ease or difficulty in the negotiating process as influenced by each of these factors largely depends on the cultural differences between the countries involved in the negotiation.

Underlying Assumptions of International Negotiations

There have been a number of approaches made to the issue of preparing for international negotiations by various authors. However, there are two important assumptions that have been found to be more evident in most of the approaches. They are

- a three-stage model of the negotiation process

- the importance of preparation for effective negotiation.

Even though there are no explicit indications of these assumptions, they form the foundation for much of what has been written about the preparation for negotiation.

Three-Staged Negotiation Process

The first assumption relates to the existence of an implicit three-stage chronological model of the process of negotiation. This model underpins the overall negotiation process, which has the pre-negotiation stage as the first step in the process, followed by a preparation stage and the final step of the negotiating stage. Much of the previous literature has based its findings based on the premise that each of these three stages encompasses a definite set of activities characterizing the respective stage. They have also based their findings on the premise that it is possible to distinguish the stages from one another based on the activities of the parties involved in the negotiation process during each of the stage.

The pre-negotiation stage generally appears to start at the point where someone – this may be a party to the negotiation or a third party intervening in the process of negotiation – first identifies the possibility of a negotiation and ends at the point when the parties to the negotiation arrive at the negotiating table. The pre-negotiation stage can be considered to have ended when all the activities connected with the stage are completed. The activities involved in this stage are

- all the parties to the negotiation have made an absolute commitment to continue with the negotiation process,

- the agenda and the structure of the negotiation have been set and agreed to by the parties,

- the participants to the negotiation are selected.

Next is the preparation stage, which covers the period from the time parties have decided to negotiate until the time when the first formal session of the negotiation process begins. This stage involves three main sets of activities;

- gathering information in connection with the negotiation,

- analysis of the information,

- planning the process of negotiation.

The activities in this stage are distinct in many respects. These activities occur away from the formal actions involved in the negotiating process and at-the-table discussion. These activities are designed to improve the prospects of the party, which undertakes the preparatory process and the activities generally take place before the parties come to the negotiating table for the first time.

The negotiating stage starts at the point of time when the parties meet formally to discuss the issues and the associated offers, proposals and concessions. The negotiating stage concludes when an agreement is reached because of the negotiations or at the point of time when one or more of the parties leave the negotiating table. The tactics for creating and claiming value, which were developed during the preparation stage, are implemented during the negotiating stage.

Traditionally the interaction between parties or their agents at the negotiating table was the defining feature of the negotiating stage. Any activities or incidents happening prior to the first formal round were considered as preliminary to the negotiating stage itself, irrespective of the purpose or nature of the activities or incidents. The literature is rife with a number of variations of this three-stage approach. Even though there may be some difference in the number of stages and their nomenclature, the activities encompassed by them do not vary too much. All of these theoretical models tend to arrive at the same conclusion that the negotiating process from the start to finish passes through distinct and chronologically bound stages, each of which possesses a characteristic set of goals and activities.

Importance of Preparation to Negotiation

The second assumption made by most of the previous literature on international negotiation is the central importance of preparation to effective negotiation. Many of the widely cited books and articles on negotiation advocate the process of preparation as the basis for an effective negotiation. Much of the literature confirms that good preparation is the path to good negotiation. In some of the literature, the faith in preparation for the success of negotiation has been made explicit. For example, Lewicki et al. (1994) view negotiation success largely as a function of effective planning undertaken prior to actual negotiation.

According to Lewicki et al. (1994), planning provides the negotiator “a clear sense of direction on how to proceed. This sense of direction and the confidence derived from it will be the single most important factor in affecting negotiation outcomes.” Raiffa (1992) after considering a number of situations in which optimal solutions to conflicts could not be reached concluded that in all these cases lack of proper preparation for negotiation has led to the situation of no resolution to the conflicts. Therefore, there is the need for effective preparation before attending any negotiating process. Other authors like Lax and Sebenius (1986) appear to have implicitly relied on the assumption of importance of preparation for justifying their emphasis on the analysis of interests, alternative courses of actions and preferences before the real process of negotiation starts.

Because of their implicit faith in the preparation for the success of negotiation, many authors have not touched the question of the extent of preparation necessary for any particular type of negotiation. Similarly, the authors have paid little attention to the types of activities that should be given priority during the process of preparation. The authors have also not addressed the issue of costs or drawbacks of preparation. In the absence of answers to all these questions relating to preparation, it can safely be assumed that the greater the preparation, the greater is the chances of the negotiation being successful.

Therefore, the more prepared negotiators arriving at the negotiating table are likely to achieve better outcomes in the negotiations. The study of the literature relating to negotiation leaves a picture that if it were possible it is better to have an infinite amount of preparation.

Problems with the Understanding of Preparation

The review of the literature raises pertinent questions concerning the broad understanding of the preparatory phase of the process of negotiation. The analysis of the two assumptions gives rise to questions on the limits to preparation and on the limits to the value of preparation. The question pertains to the determination of whether the preparation is a distinct and coherent set of activities, which are undertaken and finished, within a specific chronological stage in the process of negotiation, or is the limit less than the undertaking of the activities. Secondly, it is essential to understand the value of preparation in the sense of the extent to which one should go in preparing for the negotiation.

The first problem can be identified as the determination of the point at which preparation starts and the point at which it ends. There is ambiguity in the literature about what exactly preparation entails. If preparation can be defined to include recognizable boundaries and characteristic activities, then it may be possible for a negotiator to say that he/she has prepared to the extent necessary. However, if the boundaries are not clear and well defined it becomes difficult for one to understand where preparation begins and where it ends.

It seems reasonable to define preparation to include “the set of activities undertaken by a party to a negotiation after it has decided to negotiate but before it gets to the table” (Watkins & Rosen, 2001). Although there are no uniform viewpoints of the authors on the activities included in the preparation for negotiation, they all agree that preparation encompasses three distinct types of activities – information gathering, analysis of the information and planning for the negotiation based on the information gathered and analyzed. This definition gives a picture of preparation in that it appears to be a discrete chronological stage in the overall negotiating process.

The preparation stage is preceded by the pre-negotiation stage in which the parties agree to negotiate and it is followed by the negotiation stage where the negotiation ends. Nevertheless, this definition does not provide a comprehensive idea of the host of activities, which overlap the borders of pre-negotiation, preparation and negotiation and therefore does not fit into the three-stage model described earlier. Four different problems have been identified when treating the preparation for negotiation as a distinct stage.

Inconsistency in Definitions

When preparation is considered as a distinct stage consisting of a specific chronological set of activities, significant inconsistency occurs in outlining the activities involved. This is because of the fact that the stages of pre-negotiation, preparation and negotiation – all suffer from multiple amount of interpretations and uses. These inconsistencies make it difficult to define the limits of preparation stage clearly and cohesively.

Among the three stages, the stage of pre-negotiation is especially ambiguous. The literature makes two uses of the term pre-negotiation – one in the broad sense and the other in the narrow sense. Zartman (1989), Stein (1989) and Saunders (1985) have provided a broader definition of the term pre-negotiation. According to these authors, pre-negotiation covers all the activities starting from the earliest mediation efforts until the arrival of the parties to the negotiating table.

The definitions provided by these authors reduce the number of stages in the negotiation process to two rather than three. The definition also includes the preparation stage under the dichotomy of pre-negotiation/negotiation classification of the total negotiating process. In this case, many of the activities that have been included in the preparation stage are included in the pre-negotiation stage. Breslin and Rubin (1991), using this broad definition, make a re-division of pre-negotiation stage into two elements – creating an internal agreement with the parties and meeting at the negotiation table. Thus, Breslin and Rubin (1991) adopt more or less a three-stage model. Other researchers like Fisher (1994) and Raiffa (1992) provide a narrower definition of pre-negotiation. They limit the use of pre-negotiation to interactions between the negotiating parties or their agents. Alternatively, they include the activities in the time-period before the formal negotiations start.

“Joint brainstorming sessions, dubbed “dialoguing” or “non-negotiations” by Raiffa (1992), in which the parties come together, often with a facilitator, to share information and generate the widest possible range of options for resolving the issues, are an example of this narrower definition of prenegotiation” (Watkins & Rosen, 2001).

Although this technique may find its use in international political negotiations, it is not normally used in business negotiations. There occurs a definitional problem even with the term negotiation. Some of the authors argue that the traditional definition of negotiation, which is formal and mostly external, and at the table interaction does not cover a number of activities that take place in the two earlier process of negotiation. For example, according to Zartman (1989), “the word ‘negotiation’ is being used, as it often is, in two ways, referring both to the whole process, including the preliminaries to itself, and to the ultimate face-to-face diplomatic encounters.”

Overlapping of Preparation and Negotiation Cycles

When one tries to distinguish between chronologically limited stages of preparation and negotiation, there is likely to be a problem of overlapping preparation and negotiation cycles. This is because most complex negotiations involve several rounds of action and interaction. Generally, interactions among and within the parties, which are purely informal in nature precede and intersperse formal negotiations at the table.

“When a negotiation is conducted in multiple rounds, the activities that the parties engage in between rounds may be nearly identical to those that they undertake before the first round: gathering and analyzing information, ranking possible resolutions, planning a strategy for the upcoming round” (Watkins & Rosen, 2001). In other words, it becomes imperative that the parties prepare for the next rounds of negotiation.

In many instances, the events of the first round might serve as the preparation for the ensuing round. Instead of a single, prolonged and chronologically limited phase of preparation, which is followed by the negotiating process, pursuing repeated and overlapping cycles of preparation and negotiation, in which each round acts as the preparation for the next round and running through the entire process of negotiation until a resolution for the issue is arrived is found to be more practical and appealing.

Preparation treated as Negotiation

In many negotiations, it may be necessary for the parties to conduct complicated and delicate internal negotiations in order to arrive at an agreeable resolution in the future negotiations. The parties to a complex negotiation are rarely a single large entity. There will be a number of sides representing diverse interests, who might have spent a longer duration in arriving at a unified strategy for bringing such strategies to the negotiating table and they devise plans for the roles to be played by each member of the negotiating team in the negotiations (Putnam, 1988). In negotiations involving two rounds, the first round of negotiations serve as the preparation for the next round.

According to some scholars, there might be a difficulty in deviating from a position, which is designed after careful and elaborate deliberations and this makes the internal negotiations the only means that really would lead to some acceptable solution. In these cases preparation itself is regarded as negotiation and it is difficult to differentiate as to where the preparation stage ends and where the negotiation begins (Zartman and Berman, 1986).

The preliminary discussions between the parties, which often occur before the formal negotiations take place, are another illustration of preparation taking the role of negotiation. If the parties to a negotiation arrive to the place of negotiation in advance and enter dialogues to set the agenda, make brainstorming session on the available resolutions or fix the procedures for the negotiating process, they can be said to be involved in the negotiation even though there are no formal offers or commitments made by any side.

Nevertheless, these preliminary dialogues also call for preparation by the respective sides and therefore in effect the parties must prepare to pre-negotiate. Thus, preliminary discussions among the parties present similar issues even though they are not held at the negotiating table with each encompassing both preparation and negotiation, which makes it difficult to differentiate preparation from negotiation.

There is yet another type of negotiation, which develops during the preparatory stage. In this, the parties make strategic moves away from the table to engage in altering the conditions that the parties eventually may face at the time they arrive at the negotiating table. These are the moves, which are undertaken by the parties primarily to reduce the attractiveness of the alternatives available to the opponents, to develop supportive coalitions and to cause divisions in the opposing coalitions (Lax and Sebenius, 1986, 1991).

“For example, if one side in a negotiation succeeds in luring unaligned parties away from the other side, convincing them that the other side’s proposals would be disadvantageous, the dynamics of the negotiation may change dramatically. Although activities like this take place before the formal sessions begin, they are also clearly moves in the game—both preparation and negotiation,” (Watkins & Rosen, 2001). This position may not be present in international business negotiations.

Improper Separation of Thinking and Acting

In the three-stage model of negotiation, it usually happens that the activities connected with the three stages of information gathering, analysis and planning are dissociated from the negotiating stage. At the same time, the activities connected with negotiating like acting and interacting are removed from the preparatory stage. In the three-stage model, the process of proceeding from one discrete stage to another covers the fact that both activities like planning connected with preparatory stage and activities such as acting connected with negotiating stage are undertaken throughout the process of negotiation.

At the start of the negotiating process, when the parties begin the pre-negotiation process, usually the parties undertake researching the associated issues and the likely stands of their opponents. The parties will also be involved in evaluating and ranking the interests of the other side and the alternatives available to them. Based on this evaluation they will plan the future course of actions. It is important to note that these activities continue to be critical throughout the process of negotiation, since the parties gather information from one another and based on this information evaluate the findings and make amendments to their strategies based on the analysis of the information gathered.

Because the parties to the negotiation cannot predict the motives and moves of the other parties precisely, the negotiators are left with no other option except to continue preparing until the end of the process of negotiation.

The need for continuous preparation in international negotiations can be equated with formulating business strategies. In the strategic planning process, separating planning and implementation often leads to poor results for the corporation engaging in the strategies because even the most carefully designed strategic plans struggle to take off if the designers do not indulge in learning and revising their anticipation of the results in line with changing market events which are unforeseeable (Quinn, 1992).

Better business results can be achieved from strategic plans when business leaders keep their options open and make progress on an incremental basis based on the new information acquired and adapt their plans as they move along. Quinn (1992) states effective strategic plans “are intended only as ‘frameworks’ to guide and provide consistency for future decisions made incrementally. To act otherwise would be to deny that further information could have a value.” Negotiators need to act in the same way as business strategists and must avoid the separation of thinking from acting and learn new information throughout the process of negotiation and change their plans accordingly (Mintzberg, 1990).

Combined together, these issues of inconsistencies in definition, overlapping of preparation and negotiation cycles, preparation treated as negotiation and improper separation of thinking and acting act as the limitations to the preparation stage. These issues illustrate the reasons for the inability to identify when the preparation stage starts and when the stage ends, especially in a complex negotiation, which comprises of multi-round and multi-party involvement.

The issues discussed also illustrate that preparatory and negotiating activities overlap each other and flow simultaneously repeating themselves. The overlapping of preparatory and negotiating activities suggest that a three-stage pre-negotiation-preparation-negotiation model does not precisely distinguish between the activities and events in each stage in a situation of complex negotiation process.

In the negotiation literature, the problem of boundaries is not just the definitional issue. It has several practical implications in the ways in which one thinks and describes the negotiation process. The purpose of establishing boundaries and definitions is to determine what one assimilates and regards as important and what one misses or disregards in the whole sequence of activities in the entire process of any negotiation. Therefore, clear boundaries and definitions become critical elements in the process of good research and analysis, and in offering good prescriptions to the negotiators.

The three-stage model, which assumes that the preparatory stage ends when the negotiation stage starts, gives a misleading impression to the negotiators that they can stop preparing when they arrive at the negotiating table. The model also draws attention away from the need to continue to acquire information, analyze such information and continue planning over the entire course of a negotiation process. The separation of thinking from acting leads one to a position where there is too much emphasis on information gathering, analyzing and planning preceding the stage of negotiation and too little on learning any new information and adapting to such new information while coming to the negotiating table.

Limits of Preparation

The review of negotiation literature indicates that more preparation, which precedes the actual process of negotiation, is likely to yield better results and therefore it is advisable to invest as many resources as possible in preparation. Nevertheless, there is no indication in the literature as to the point where preparation is enough or is too much. Just as the boundaries, problems deal with the meaning of preparing to negotiate, the second issue of limits to preparation deals with what it means to prepare enough to negotiate.

Limits on Resources

One of the most fundamental limits confronted by a party to a negotiation is the limitation imposed by the finite resources available for negotiation. Even the best-prepared negotiating team might have been subjected to the “constraints on time, expertise, money, data, access to documents” (Watkins, 2002) and other tangible resources. Limitations on available resources act as a restriction on the magnitude of the overall preparation efforts of the parties to the negotiation. It is not always possible for the negotiators to prepare as much as they would like to because of these limitations and this fact is often overlooked by the negotiation literature.

The limitations on various resources also force the negotiators to undertake a series of difficult cost-benefit calculations and decisions on allocating the available resources. The decisions may relate to the time to be devoted to information gathering and the time needed for analyzing the gathered information.

They have to make hard decisions on the time to be allotted for planning and on the gathering of the additional information as to whether such additional information to be gathered through more research is really worth the cost or whether it is worth the while to spend the additional time on analyzing the already gathered information. The need to make these types of decisions forces negotiators make a careful analysis of the different priorities and to decide in advance which types of preparatory activities are likely to give them greater benefits during the process of actual negotiation.

Limitation on Information Availability

Even when the parties have infinite resources available to them, they may not be in a position always to get what they want while preparing for the negotiation. Negotiations represent games of incomplete information. There are some fundamental reasons, which lead to this incompleteness in the information available. They are:

- negotiations are characterized by a high degree of complexity, involving a number of variables, which interact with each other in mostly unforeseeable ways;

- negotiations suffer from high uncertainty because of an inherent lack of knowledge about the future state of the world;

- negotiations also possess the character of high ambiguity, which restricts the chances of getting complete information about one’s own interests and alternatives or those of the opponents and in addition there would always be shifts in the interests and alternatives;

- negotiation also suffers from the limitation that parties to a negotiation engage in various deceptive activities of deliberately concealing information from the opposite side or providing misleading or inaccurate information on the party’s interests and alternatives;

- negotiations are basically indeterminate, in that it is the interaction of the parties during the process of negotiation which determines the specific agreement within the range of all possible agreements that are possible. It is to be noted that no amount of information gathered would be able to predict the course of that particular interaction which decides the specific agreement;

- negotiations represent a strong non-linear phenomenon, in which minor changes in the initial conditions are likely to lead to major consequences.

It may also happen that events occurring at an early stage of negotiation may become irreversible at a later point of time in the process of negotiation. In the process of negotiation, it is possible that there are a large number of initial conditions, in which even minor changes might affect the outcome of the process of negotiation. For instance, the simple event of whether the negotiators shake hands when they enter the negotiating room first may influence the course of the negotiation.

This will happen irrespective of the issues involved and the interests of the parties at stake. There are other factors like the chance of discovering common acquaintances, factors of gender and age of the negotiators or even the choice of the office building, which is used for negotiation, which might affect the outcome of the process. Just as it happens with many other non-linear systems, the important aspects of negotiation may become irreversible.

For example, a lost temper at an early stage of negotiation is likely to impair the relations between the negotiators throughout the process of negotiation until the end and it may not be possible to repair any damage once done. It is also not possible that negotiators could prepare for the impacts of non-linearity in the process of negotiation. At best, they can only recognize and adapt to the effects as and when the incidents occur during the course of negotiating process.

These reasons prevent the negotiators from knowing every piece of information they would like to know and any amount of preparation cannot equip them to know the extent they want to know. For example, one of the principal activities in the process of preparing is to gather information on the interests and alternatives of the other party.

Nevertheless, irrespective of whatever time, efforts, and other resources the negotiators apply in this activity, they may not be in a position to gain a complete understanding of the other party’s interests and alternatives because of the reasons listed above. It may not be possible for the negotiators to perceive the interests of the other party even if they apply infinite resources. In addition, the resources invested in the activity will provide only diminishing returns, as it is often difficult to obtain more and more information even on applying additional resources. “While the value of devoting some effort—and perhaps significant effort—to this activity is undeniable, it is equally clear that there is a limit to its usefulness. The information sought may simply not be available” (Watkins & Rosen, 2001).

Cognitive Limits

The characteristics and capacity of human perception and reasoning limits the value of the preparation process. These limits can be called “cognitive limits.” Although the cognitive limits are less obvious than the limitations emanating from finite resources and incomplete information, the cognitive limits may be important in deciding the possible extent of the preparation. Unlike the limitations of resources and information, the cognitive limits not only restrict the magnitude and efficacy of the preparation process but also actually weaken the process by reducing the ability of the negotiator to achieve a desirable outcome of the negotiation.

The nature of human perception and reasoning can affect some basic elements of preparation. To illustrate, analyzing one’s own interests being one of the activities of preparation, although crucial, carries with its own set of dangers. One of the fundamental assumptions underlying the analysis of interests is the stability of the interests and preferences of the negotiators. If the interests and preferences are stable, then it becomes easier to analyze, evaluate and solidify in advance, which acts to reduce the risk of the negotiators being sidetracked or losing sight of the original objectives.

The potential cost of this activity also needs to be recognized. However, interests and preferences, which are considered as stable and known cannot be expected to evolve or change during the process of negotiation, with the new opportunities arising or new information becoming available. These changes in preferences often become an important component in the dynamics of negotiation, which allows the negotiators to take into account new information, adapt to changes in their relationship and expand the possibilities of arriving at agreeable solutions.

However, considering the interests and preferences as stable becomes additionally problematic in the cases where complex internal negotiations are expected to establish a position covering the external negotiations. “Once an internal coalition has coalesced around an apparently stable set of interests, participants in the external rounds may have lost virtually all flexibility in responding to new proposals and concessions,” (Watkins & Rosen, 2001).

Similarly, negotiators who have invested a substantial amount of time and effort in the analysis of their own interests and preferences may tend to become overcommitted to the outcomes of these processes, which in turn is likely to create rigidity in their convictions about what would constitute an acceptable agreement. Keeney and Raiffa (1992) observe that a significant amount of work has been done on the process of quantifying interests and alternatives and in assigning values to the issues and possible outcomes so that negotiators could arrive at the negotiating table with a precise understanding of their preferences and the ability to score the other party’s offers and proposals.

This process actually facilitates the negotiators in developing elaborate scoring systems and in investing significant time in assigning values for the likely offers and proposals. There is one danger associated with the negotiators putting too much effort in analyzing the interests and alternatives in that they become committed to the systems they have developed. Such commitment encourages them to expect to obtain a predetermined score. This makes them judge the options and outcomes purely in terms of scores or points. Consequently, there may occur a loss of flexibility, creativity and receptivity to compromise which are essential qualities for achieving mutually beneficial outcomes.

The risks, which are inherent in analyzing one’s own interests and preferences, are even more apparent in the process of analyzing the interests of other parties. This prescription applies only to those who undertake the process of preparation preceding the negotiation process and one cannot dispute the value of such analysis. However, there is a high probability of stereotyping in which one party assumes its interests would match with those of whatever large group the party is associated with and this probability cannot be ruled out. This situation is most likely to arise in the case international negotiations.

There is also the probability of making wrong guesses about the things which matter, to the other party. Such mistaken beliefs and assumptions about the interests and alternatives of the other party have the effect of narrowing the range of options generated and considered in the course of the process of negotiation and they reduce the chances of arriving at an efficient agreement. If one of the parties becomes confident about his/her understanding of the interests of the other party, it may also lead to selective perception at the point of time when the parties begin to talk. Such confidence makes the negotiators less likely to listen carefully to the views of the other party and ask intelligent questions as they are sure that they already know the answers. This type of selective perception combined with stereotypes and mistaken assumptions might lead to self-fulfilling prophecies and opportunities for sabotaging likely agreements (Rubin, Pruitt and Kim, 1994).

The effect of these cognitive limits is that as and when the deliberations in the negotiating table proceeds and there is an exchange of views and proposals among the parties, the negotiators may have to “unlearn” many of the things that they presume they have learnt before arriving at the negotiating table. The analysis and planning that might take place before the parties meet at the negotiating table might have been based on information, which was incomplete. In order to avoid becoming stuck to initial assessments which may not be accurate, the negotiators must be willing to amend or even discard the beliefs formed earlier in the face of conflicting evidence. Thus, because of the effect of the cognitive limits the negotiators who have spent considerable time and efforts in gathering information, analyzing it and devising detailed plans may not be willing or able to amend their beliefs and adapt them to the course of the actual process of negotiation, which contain face-to-face discussions.

Resource, informational and cognitive limits inflict major constraints on the process of preparing to negotiate. These limitations suggest that there is a duty for negotiators to think carefully about the goals of preparing. They also advise that the negotiators must consider setting priorities as a crucial first step and that unlearning is as important as learning and it is even possible that they might get “too prepared” for the negotiations. Even though preparation is an important step in the negotiation process, it has some potential drawbacks. “Even the most basic prescriptions, such as those about analyzing interests, entail tradeoffs that a prospective negotiator must recognize and address,” (Watkins & Rosen, 2001). It is a fact that the existing literature has ignored the limits to preparing greatly and one cannot expect much help from the literature on the extent to which one should prepare to continue with the negotiation process.

Summary

The boundaries and limits discussed above point to the fact that there needs to be a complete rethinking of the process of preparing to negotiate. Based on the discussion it can be stated that preparation cannot be treated easily as a cohesive bounded stage. It appears that the activities undertaken during the stages of pre-negotiation, preparation and negotiation are not entirely different. Therefore, it is difficult and often not useful to distinguish one chronological stage from the other. It is problematic particularly with the preparation stage to deem it as a distinct stage because it is ambiguous because of the fact that all the three activities associated with preparation namely information gathering, analyzing and planning happen to take place through the negotiating process. It is not possible to separate thinking from acting.

Similarly, the existence of resource, informational and cognitive limits force the negotiators to make a cost-benefit analysis through the entire process of negotiation. Because of the fact that the activities connected with information gathering, analyzing and planning entail cost and are subject to diminishing returns, the negotiators must compare the costs of undertaking the activities with the benefits likely to occur from such activities. Based on such cost-benefit analysis the negotiators should make the allocation of the available resources. More particularly the negotiators have to make their decisions from three different perspectives –

- the amount of time and resources to be invested in information gathering, analyses and planning away from the negotiating table as against at the negotiating table,

- the time and resources to be invested in acting to adapt to the circumstances away from the negotiating table as against at the table

- the ways of learning both away from and at the table.

The characteristics and context of the situation facing the negotiators will have to be taken into account by the negotiators in making these decisions.

An alternative to the three-stage preparation model, which advises more preparation, a model of repeated cycles of learning and planning will be of more use. In this model, learning implies gathering and analyzing of information available from whatever sources both away from the table and during the course of negotiations at the negotiating table.

Planning encompasses using the gathered information to devise plans for possible future action and to identify the other information needed both prior to the start of the negotiation and during the negotiation process. There is another stage of acting involved in this model, which implies taking steps to change the conditions, which may include moves away from the table. It also includes sharing of the available information emanating from any brainstorming session and exchanges of offers and proposals in a traditional way at the negotiating table. This model envisages the progression of the negotiators in an adaptive way through alternative cycles of the three core activities involved in the model.

The most important difference between this model and the theoretical three-stage model is the central role taken by learning throughout the process of negotiation. In this model, negotiation is not represented by a plan and then implemented as a process with one time learning and planning before arriving at the negotiation table. Instead, this model suggests that negotiation is a process of acquiring new information on a continuous basis from all the available sources including knowing the interests and alternatives of the other party. Based on such knowledge the negotiators adjust their expectations and devise new strategies based on the new information gathered.

This model also provides for managing the resource, informational and cognitive limits which find an inherent place in a negotiation process concentrating on the major decision areas discussed earlier. The limitations on resources do not allow the negotiators to do an unlimited amount of information gathering, analysis and planning based on the analyses. The new model enables resource allocation on an explicit basis and provides better solutions such as making tradeoffs between learning before and during the process of negotiation.

Unambiguous recognition of information limitations underlines the need to take the peculiar characteristics of specific negotiations into account when making tradeoffs between learning away from and during the course of negotiation. This leads to the formation of a contingency theory of learning, planning and acting in negotiation. In the case of negotiations, which are not complex uncertain and unambiguous, most of the information, which a negotiator wants to know can be learnt in advance and there will be very little to be learnt during the negotiation.

The negotiation in this case can proceed as portrayed with most of the planning done and with most of the acting carried out in one or few steps during the negotiations at the table. On the other hand, in the case of complex, uncertain and ambiguous negotiations, there are several limitations acting on the extent to which the negotiators can learn before they arrive at the negotiating table and on the resources, which could be invested in gathering information upfront and analyzing the information gathered.

Under such circumstances, negotiators can benefit more by using the time planning to learn once they arrive at the negotiating table. When faced with a high level of uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity, it is advisable that the negotiators adopt an incremental step approach through the entire process of negotiation, learning through the interactions taking place during the course of negotiation.

Because of the existence of cognitive limitations, the rigorous information gathering and analysis recommended by the literature may make the negotiators resort to misleading assumptions about the interests of other parties or make them rigid in their approaches to the whole negotiation process. In contrast to this position, concentrating on a continuous learning process both away from and at the table would enable the negotiators to adopt a scientific approach of hypothesis testing and deciding on the issues. A negotiator who goes to the negotiating table with a hypothesis about the interests and alternatives of the other party will attend to the negotiation with the goal of testing the hypothesis and will be in a position to unlearn where necessary.

The negotiator who is willing to unlearn is likely to ask a different set of questions during negotiations than the one who relies on the accuracy of his upfront analysis and leading assumptions to interpret the actions of the other party. The learning negotiator will also realize and look for shifts in the preferences and values of the other party during the course of negotiation. Therefore, this model help the negotiators to balance the investment of valuable resources in information gathering, analyzing the information gathered and planning in advance with learning and unlearning during the process of negotiation.

Analysis

Neslin and Greenhalgh (1983) observed that negotiation is one of the important matters for both sellers and buyers in international trade (as cited in Simintiras & Thomas, 1998). Gilsdorf (1997) as cited in Woo & Prud’homme (1999) indicate that negotiation is the most challenging task in communicating in business dealings. Negotiation is considered as the process of communicating backward and forward in order to discuss the issues and arrive at a resolution which both parties could not satisfy initially (Foroughi, 1998). “Negotiation is a process for managing disagreements with a view to achieving contractual satisfaction of needs” (Gilles, 2002).

Negotiation in international trade is a kind of social interaction entered into with the intention of reaching an agreement for two or more parties having different objectives or interests whom they think are important for themselves (Manning & Robertson, 2003; Fraser & Zarkada-Fraser, 2002). Differences in cultures, environments, communication styles, political systems, ideologies and customs or protocols make situations more complicated in cross-cultural negotiations (Hoffmann, 2001; Mintu-Wimsatt & Gassenheimer, 2000).

Role of Culture in International Negotiations

“Cultures are defined by values and norms. These may vary according to national, organizational, regional, ethnic, religious, or linguistic affiliation, and by gender, generation, social class, and family levels” (Chen and Starosta cited in Aydin & McIsaac, 2004). According to Simintiras and Thomas (1998), cultures are accepted values and norms, which lead people to have different ways in their thoughts, feelings and behaviors. “Culture has been defined as accepted beliefs, behavior patterns, values, and norms of a collection of individuals identifiable by their rules, concepts, and assumptions”, Salacuse as cited in Hendon, Roy, & Ahmen, 2003).