Introduction

Everybody in this world would certainly agree that happiness is essential in life and consideration of what contributes to happiness is very worthwhile pursuit. This notion recognizes that there is an individual propensity to a certain level of happiness, however positive psychologists would argue that happiness is not hardwired – only about 25% as opposed to 40-60% for most hereditary traits. Rather it is malleable and can change with context. This makes it a particularly important issue for organisations. In the organisational context, often money or material wealth are given considerable ‘air-time’. Yet wealth and material benefits aren’t always a key to happiness; for example, it has been shown that lottery winners are happy in the short term, but after a little while their happiness levels revert back to the norm. Despite inconclusive link between workers’ happiness and productivity in the workplace, there seems to be a general agreement that happy workers are to be productive workers. While wellness and life satisfaction studies conducted on working populations can be found in journals in diverse fields such as public health, education, and criminal justice, these studies often fail to examine the nature and context of work, reporting simple correlational results as the most vital achievement is the happy workforce, on the whole (Ali, 2017; Sheikh Mohammed Bin Rashid Al Maktoum, 2017; Yaghi and Al-Jenaibi, 2017).

Background of the Study

In recent years, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) government has worked towards establishing a national program for happiness and wellbeing. Part of this program is the strategic implementation of positive practice in sectors such as education, healthcare and in government ministries. Vice President and Prime Minister of the UAE and Ruler of Dubai, His Highness Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum has stated that the government’s mission is to promote positivity by implementing policies, programmes and services that contribute towards the development of a positive and happy community (Sheikh Mohammed Bin Rashid Al Maktoum, 2017; UAE Cabinet, 2016), with the main tasks of ensuring that conditions are favourable for the delivery of happiness to individuals, families and employees by promoting positivity as a value in the community. Realizing this mission from February 2016 is the responsibility of the newly appointed Minister of Happiness, Her Excellency Ohood Al Roumi, charged with establishing the happiness, satisfaction and positivity of citizens as a national priority. A federal budget of 49AED billion has been allocated for 2016 alone which has, in part, enabled the Minister to work with more than fifty government entities in the national program for happiness (Remeithi, 2016).

The national UAE Program of Happiness features a set of three initiatives (Sheikh Mohammed Bin Rashid Al Maktoum, 2017):

- Happiness in policies, programmes and services of all government entities and work environments;

- Promotion of values of positivity and happiness as a lifestyle in the UAE community

- Development of innovative benchmarks and mechanisms for measuring happiness in the community (“Mohammed bin Rashid”, 2016).

The aim is to make happiness a lifestyle in the UAE community as well as the noble goal and supreme objective of the government (Emirates News Agency (WAM), 2016), underscoring the importance of creating a positive environment and instilling values of positivity in ministries and government employees. The Prime Minister of the UAE has emphasised that policies, programmes, services and work environment in ministries should focus on happiness and enhance coordination with the private sector to achieve this target. He further acknowledged the need for accurately measuring happiness among members of the community.

The Minister of State for Happiness addressed the ruler’s aim by initiating a charter for happiness and positivity which will be unveiled along with key performance indices. Part of this initiative is the commencement of a year-long training program, the first of its kind on a national level, for 60 Chief Happiness and Positivity Officers who will ensure the program’s success (Sheikh Mohammed Bin Rashid Al Maktoum, 2017). These officers will serve in councils established by the Minister of Happiness in every other ministry and led by the respective minister. The goal is to bring the ministries’ initiatives in line with the government’s happiness objectives. Her Excellency Ohood Al Roumi stated that the role of the Ministry of State is to assess the effects of these initiatives on citizen and workers satisfaction levels.

Workplace-related happiness has become a topic of interest in today’s employment world. Happiness at work can be seen as a by-product of work-related engagement and meaning. Happy workers exemplify engagement while using their strengths at work and find meaning in using their strengths for a higher purpose. These conceptualized constructs of happiness are not genetically limited, since happiness can increase as these aspects increase (Sheikh Mohammed Bin Rashid Al Maktoum, 2017; Jiang, et. al., 2012; Wright, et. al., 2007).

Research Problem

Work is a key source of pride and meaning in employees’ lives. Many organisations have ignored this fundamental lesson. When a workplace is designed and managed to create meaning for its workers, they tend to be more healthy and happy. In their turn, healthy and happy employees tend to be more productive over the long run, generating better goods and more fulfilling services for their customers and the others with whom they interact and do employment. These three things, namely, health, happiness, and productivity, are the essential ingredients of a good society. Improvement in productivity alone, which is almost the sole emphasis of many organisations today, is not enough (Sheikh Mohammed Bin Rashid Al Maktoum, 2017). Therefore, there is a need to understand the problem of workplace happiness achievement in an in-depth manner to ensure that employees will be motivated to remain effective and become happy in the long-term.

Practically, it seems clear that if there is any hope for people to find general happiness in their lives today, they must be happy at work. Work by itself, of course, cannot make a person happy, but a person cannot be genuinely happy if he or she is unhappy at work. Just as individuals need role models to guide their development, so do organisations. In relation to the hadith: “Verily, Allah loves that when anyone of you does a job he should perfect it” (Al-Bayhaqi). Ihsan is not always expecting perfection from yourself, because the only one who is perfect is Allah. Of course, as Muslims, whenever the UAE employees undertake a job, they try their best to make it excellent, but that does not mean that they spend a week doing a job that usually takes one day, just so that every nick and corner is honed to perfection. That is pure waste of time, and Islam places a lot of value on time, and, furthermore, it is also a sign of obsessive compulsive disorder. Islam is a balanced religion, and excessiveness in religion is disliked to say the least. In other words, though Allah alone is perfect, employees should strive for it in all of our endeavours.

Exploring the role of happiness in the workplace, it is also essential to focus on the recent studies that target similar themes in other countries of the world. The evidence shows that happiness, hope, self-esteem, optimism, and efficacy are the concepts that closely intertwined. Malik (2013) defines positive organisational behaviour (POB) and utilises the term of optimism as the core prerequisite of happiness. The author integrates information acquired primarily from the American and international scholarly literature to provide relevant ideas. It is emphasised that by fostering optimism in the workplace, leaders may achieve greater problem-solving and employee satisfaction. Building upon Bandura’s theory of social learning theory with the focal concept of self-efficacy and Kumpfer’s theoretical model resilience, Malik (2013) specifies the need to promote happiness in employees as a way to benefit both people and organisations. In other words, the mentioned study contributes to the understanding that today’s workplace needs to be designed to provide happiness.

A person is inseparable from his or her feelings and emotions; therefore, work as an important component of life should bring happiness. The components of happiness at work largely depend on individuality since all people rejoice in different ways, albeit sometimes similarly. According to Oswald, Proto, and Sgroi (2015), the feeling of happiness is the correspondence of performance and the environment to the personality of a certain employee. For example, tasks and dynamics compose one of the most critical areas; some people prefer monotony, while others stick to creativity, constant risk, and the solution of non-standard problems (Oswald et al., 2015). The ability to control the situation also differs, depending on the skills and knowledge of employees. Multitasking or, on the contrary, a clearly defined task within the allotted time – everyone selects which one to follow. If there is not enough of a component, then a person most likely will not be happy at work yet will look for other options or, even worse, be dissatisfied with the workplace environment (Milner et al., 2013). The meaning of such an employee for an organisation will be insignificant.

As it can be viewed from the above paragraph, the problem of happiness achievement is complicated by the fact that happiness is not a static concept, and its understanding may vary among employees. The question is how to make happy as many employees as possible. The study conducted by the scholars from the University of Warwick, England demonstrates that a series of experiments proved the link between employee productivity and happiness, yet the ways to establish it remain unclear (Oswald et al., 2015). More to the point, the above study illustrates the need to elaborate on specific programs and policies to introduce the concept of happiness into the workplace. In this regard, it becomes evident that further research is needed to clarify the nature and opportunities of such a link, so that the UAE organisations may formulate their own policies and bring more value to the workplace.

Many organisations cannot clearly represent what they seek while speaking about happiness and optimism, while precise attention to employees adds more positive emotions and improves the atmosphere in the team. It is rather significant to have a clear understanding of the strategy and direction of business development, openness in relations with employees, and adaptability to market changes, situations, people, and priorities, as stated in the study focusing on employee happiness in China (Cheng, Wang, & Smyth, 2014). This study reveals that new-generation migrants are less happy compared to the first-generation migrants, which is caused by the growing economy and the concept of subjective wellbeing.

In his book “Delivering Happiness”, Hsieh (2013) recommends that employers create a sense of progress and speed of movement in employees. The author states that earlier in Zappos, employees moved up the career ladder every eighteen months provided that they met all the requirements necessary for this (Hsieh, 2013). Then, the company switched to a new system of small career advancements every six months. As a result, the level of happiness of people was much higher because they felt constant progress and growth. This example shows that achievable and transparent prospects for the professional development are attractive to employees, and they are likely to provide happiness. At this point, both professional and personal growth opportunities should be taken into account.

This study will explore a series of questions of interest to economists, behavioural scientists, employers and policy makers. The impending research questions are: Does happiness effect productivity at work? What kind of happiness? Does any other construct effect this relationship at work? How? There is still limited empirical research of workplace or employee happiness relationship with productivity in the Middle East region. Nowadays, the government of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) is seeking solutions to many urgent social problems (Al-Qaiwani, 2017). The most important tasks of the government involve taking necessary measures to improve the quality of life of its citizens.

An important aspect of this issue is that there is a need to focus on the level of citizens’ happiness that defines their well-being. As it is clear from the experience of many countries, to maintain and increase the level of happiness of the people. Another fact that contributes to the significance of future research is that there is a need to extend the knowledge regarding government employees’ happiness in connection with the initiatives of the government aimed at increasing their happiness (Miller and Miller, 2016).

Theoretically, additional research in different settings and theoretical perspective shall be collected to support the research conducted in an attempt to better understand work-related happiness, engagement, and meaning, and the importance of those factors in today’s employment world (Yaghi and Yaghi, 2014). Managers need to look at the ingredients within the recipe to address happiness in an organisation. However, in the Middle East Region, there is still absence of empirical Islamic happiness scale which also encapsulates the spiritual and emotional wellbeing element.

The organisational context has a number of major elements where policies and practices can be put in place to support satisfaction and development in individual employees. It have known for quite some time that within the organisational context there needs to be a focus on elements such as organisational climate, the philosophy and ethos of the organisation. Another aspect would be social relationships and how supportive management is. Yet another would be, for example, how supported the individual feels in achieving their career and work aspirations, with such measures as training and development and career support. In an organisational context, there are issues other than money which must be given consideration in supporting well-being, and they are major constituents of the recipe for happiness.

Despite the recently increasing attention, empirical studies on employee spiritual and emotional happiness at work are still lacking (Ali, 2017; Almazroei, 2014). Although adults spend much of their time working, traditional life satisfaction or happiness studies have examined non-work populations such as students, patients, children, or adolescents. Thus, researcher believes the lack of attention paid to employee happiness in the management field is a critical research gap (Yaghi and Al-Jenaibi, 2017; Yaghi and Yaghi, 2014). As the happiness literature has ignored the work domain, the management literature has largely ignored the concept of employee well-being.

It is only recently that happiness at work or employee happiness that is believed to be associated with both work and personal life outcomes has begun to be researched in the field of human resources (HR) and organisation behaviour (OB) (Tenney, et. al., 2016). Thus, contemporary scholars are confronted with an interesting challenge. In the sections that follow, researcher will explore these ideas in greater detail. In particular, for reasons to be elaborated above, the present paper proposes that the relation between employee happiness and productivity is moderated by UAE public sector employee spiritual and emotional wellbeing (Al-Qaiwani, 2017; Sheikh Mohammed Bin Rashid Al Maktoum, 2017; Yaghi and Al-Jenaibi, 2017).

Research Objectives

The main purpose of the study is to investigate the level of impact of employee satisfaction and employee happiness as well as their impact of employee productivity. Therefore, the research objectives are:

- To identify the link between governmental employee happiness and performance in the UAE settings. It is expected that the UAE environment creates a specific attitude towards work due to the local religious and cultural peculiarities.

- To measure the UAE employees’ level of instilled happiness, focusing on spiritual and emotional wellbeing. The evaluation of happiness may be difficult since employees may perceive it in various ways; nevertheless, it is still possible to interview them and address this objective.

- To identify the behaviour, events, or any other issues that make employees feel happy at work. It goes without saying that not only remuneration but also non-material benefits help employees to stay engaged and motivated to work better. By revealing these issues, a researcher will better understand how to manage happiness in an organization.

- To measure the productivity of UAE employees. The consideration of the official documents along with the statistics will be beneficial to assess employee productivity.

- To evaluate the relationship between UAE employee happiness and employee productivity. By comparing and contrasting the above issues, a researcher will identify their relationship, including its nature, any positive or adverse impacts, and opportunities.

- To evaluate the moderating effect of UAE employee spiritual and emotional wellbeing on the above relationship. Taking into account the emotional and spiritual condition of employees will contribute to the greater reliability of the proposed research.

- To formulate policy, strategies, and empirical Islamic Happiness Scale in instilling the culture of employee happiness and positivity among the UAE public sector employees. The above ultimate objective will systematically integrate the previous objectives and promote the formulation of relevant recommendations that may assist the UAE organisations in implementing a happiness culture.

Research Questions

Based on the problem specified in the previous section as well as the research objectives, the following research questions may be formulated:

- What is the level of employee happiness in the government sector of the UAE?

- What are events, behaviours, or any other factors that make employees feel happy when they are at the workplace?

- Does employee happiness make them more productive at the workplace?

- Does any other external or internal variable affect the relationship between employee happiness and effective performance?

- What can change the ratio of happy and unhappy employees for the better? How feasible is it in the conditions of the Islamic world?

- What are spiritual and emotional issues that should be taken into account while designing happiness provision programs and policies?

- How does the culture of happiness may be implemented in the UAE settings? What steps should organisations take to strengthen happiness of employees?

Significance of Research

Given the continuous pursuit of developing and implementing strategies to maximize organisational effectiveness, organisations are studying and more frequently beginning to utilize theories and concepts from the employee happiness, which provides opportunities for understanding the impact of organisational strategies on human behaviour in the workplace, and why some strategies and dynamic capabilities may be more generative than others (Lee, et. al., 2014). This is especially relevant as positive psychology has flourished in the last decade. It may come as a surprise to learn that companies in which the focus is on amplifying positive attributes (loyalty, resilience, trustworthiness, humility, compassion), rather than combating the negatives, perform better, financially and otherwise. Positive psychology has emerged and gained momentum as an approach that redirects focus from what is wrong with people or organisations toward one that emphasizes human strengths that allow individuals, groups, and organisations to thrive and prosper. The overall goal of positive psychology is to create organized systems that actualize human potential (Jiang, et. al., 2012).

Assuming that these findings may be replicated by future studies, they could have implications for individual betterment and management practice. In particular, organisations may want to pay closer attention to the wellness of their workforce. Generally speaking, employee-focused, positive psychological based work interventions can take three general forms such as composition, training, and situational engineering. Composition focuses on selecting and placing individuals into appropriate positions, while training emphasizes assisting employees so that they better fit their jobs. Finally, situational engineering focuses on changing the work environment to make it more closely fit the needs and abilities of one’s employees. While employee happiness has implications for each of these approaches, we may focus our attention on training and situational engineering.

Considering the great role that happiness at work plays in modern society, this government initiative seems to be a breakthrough, able to drive the wellness of the citizens to the next level and enhance relationships between the government and common people working in the United Arab Emirates. The problem that encouraged me to choose this very topic is also connected to the fact that there are few sources keen to wellness in the United Arab Emirates. The research gap that exists in the field needs attention because it is impossible to build a happier society without taking into consideration the attitudes and needs of employees all over the country.

Scope and Limitation

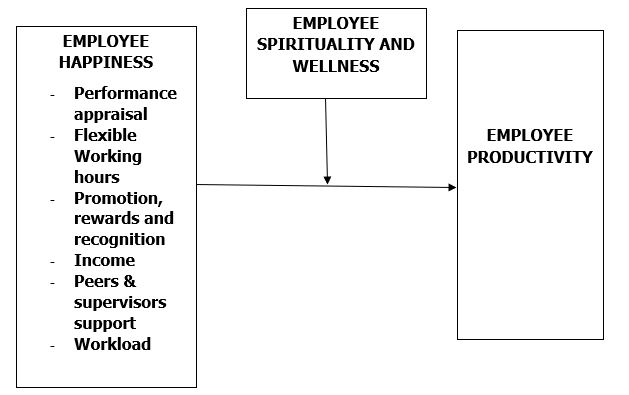

This research will be conducted in the UAE public sector. The respondent will be the randomly selected government employees. The independent variable is employee happiness and the dependent variable is the employee productivity. The employee spiritual and emotional wellness is the moderator variable. The respondents will be the first-level administrators employed by a large (over 5000 employees) government agency in the UAE to participate in the study by means of a direct contact procedure. More specifically, the researcher will schedule a time to individually meet with the administrators in his or her office.

Literature Review

Introduction

Happiness at work is an umbrella concept that includes a large number of constructs ranging from transient moods and emotions to relatively stable attitudes and highly stable individual dispositions at the person level to aggregate attitudes at the unit level. In the workplace, happiness is influenced by both short-lived events and chronic conditions in the task, job and organisation (Ali, 2017; Almazroei, 2014). It is also influenced by stable attributes of individuals such as personality, as well as the fit between what the job and organisation provides and the individual’s expectations, needs and preferences. Understanding these contributors to happiness, together with recent research on volitional actions to improve happiness, offer some potential levers for improving happiness at work (Joo, et. al., 2017; Sheikh Mohammed Bin Rashid Al Maktoum, 2017)

Thoretical Perspectives

Happiness is a holistic ideal. It speaks to the whole person, one whose whole life is complete in the sense that his or her reasonable desires are fulfilled over his or her lifetime. He or she is secure in the sense that others will rally around to aid in the event that misfortune strikes. Happiness is not primarily rooted in receiving sensual pleasure, honours or money; although these may be a contributing part of a greater pattern of positive factors. Rather, happiness derives from three key defining characteristics:

- Freedom. Happiness mostly results from an individual’s ability to make choices. Happy people are those who can think independently and are free to choose.

- Knowledge. Happiness requires information, knowledge and the ability to reason. If workers are allowed to make important decisions they need to know about the employment, how the world works and something about human psychology. Importantly, they need to know how to make intelligent decisions by means of practical reasoning.

- Virtue. Happiness requires moral character. Interestingly, most organisations lack formal ethics or character development programs, yet each has been given prestigious ethics and related awards. Ethics and character building permeate everything they do. Moral training comes in large part from the corporate visions and foundational principles that all employees learn, assimilate and continue to practice. This moral guidance, coupled with the responsibility to make decisions, helps develop the moral character and intellectual expertise necessary to make good decisions. Making good decisions results in authentic and justifiable pride, self-esteem, self-respect, self-approval, self-admiration, self-actualization. All of this is essential for reducing the negative effects of stress, for enhancing one’s ability to cope and strong feelings of self-efficacy.

Mcgregor’s Theory

Being in a reliable work environment increases retention, productivity and employee wellbeing, while also promoting a better employment culture (Sanna, et. al.,1996). Economic and managerial studies have only begun to examine the possible existence of causal links between productivity and happiness. Evidence of a link between happiness and productivity might illuminate the microeconomic foundations of the observed correlations between job satisfaction and stock-market productivity. A correlational study using longitudinal data for Europe shows that an increase of one standard deviation in a measure of job satisfaction within a manufacturing plant leads to a 6.6% increase in value added per hours worked. The economics literature that is relevant to analyze the effect of spiritual and emotional well-being on productivity does not examine the effects of happiness directly but mainly explores the theoretical differences between intrinsic motivation (based on internal psychological incentives) and extrinsic motivation (incentivized payments).

A study of the interactions among self-deception, malleability of memory, ability, and effort considers the possibility that self-confidence enhances the motivation to act, which is consistent with the notion of a connection between affect and productivity. The study uses an economic model of why people value their self-image to explain seemingly irrational practices such as handicapping self-productivity or practicing self-deception through selective memory loss. In general, such studies reflect increasing interest among economists about how to reconcile external incentives with intrinsic forces such as self-motivation. For example, workers may boost their confidence in having the skills needed to achieve a specific target, which in turn increases their motivation to tackle the job (Cropanzano and Wright, 2001).

Theory Y was an idea devised by Douglas McGregor in his 1960 book “The Human Side of Enterprise”. It encapsulated a fundamental distinction between management styles and has formed the basis for much subsequent writing on the subject. Theory Y is a participative style of management which “assumes that people will exercise self-direction and self-control in the achievement of organisational objectives to the degree that they are committed to those objectives”. It is management’s main task in such a system to maximise that commitment. Theory Y gives management no easy excuses for failure. It challenges them “to innovate, to discover new ways of organising and directing human effort, even though we recognise that the perfect organisation, like the perfect vacuum, is practically out of reach”. McGregor urged companies to adopt Theory Y.

Only it, he believed, could motivate human beings to the highest levels of achievement (Zelenski, et. al., 2008). Management influenced by this theory assumes that employees are ambitious, self-motivated and anxious to accept greater responsibility and exercise self-control, self-direction, autonomy and empowerment. Management believes that employees enjoy their work. They also believe that employees have the desire to be creative at their work place and become forward looking. There is a chance for greater productivity by giving employees the freedom to perform to the best of their abilities, without being bogged down by rules. Theory Y manager believes that, given the right conditions, most people will want to do well at work and that there is a pool of unused creativity in the workforce. They believe that the satisfaction of doing a good job is a strong motivation in itself. Theory Y manager will try to remove the barriers that prevent workers from fully actualizing themselves (Zelenski, et. al, 2008).

Many people interpret Theory Y as a positive set of assumptions about workers (Gasper and Clore, 2002). Thus, Theory Y management suggests that happier people will be more productive, and many empirical findings are consistent with this idea. For example, Bolger and Schilling (1991) found that employees who were more prone to negative emotions were more likely to use contentious interpersonal tactics and thus provoke negative reactions from co-workers. According to Cropanzano and Wright (2001), less happy employees are more sensitive to threats, more defensive around co-workers, and more pessimistic. Conversely, happier employees are sensitive to opportunities, more helpful to co-workers, and more confident. Truly miserable employees, those who are depressed, are likely to display little energy or motivation, and, thus, accomplish little.

Fredrickson (2001) suggests that positive emotions function to ‘broaden and build’ skills and social bonds. For example, individuals in positive mood states are more cooperative, more helpful, and less aggressive (Isen and Baron 1991), likely improving productivity in so cordial or collaborative work contexts. In addition, positive emotions may lead to better productivity in more complex jobs by enhancing creative problem solving (Madjar et al. 2002). Beyond their immediate effects (on creativity or social facilitation), positive emotions may also aid in building resources for future productivity. That is, positive emotions likely foster new skill acquisition and the building of social capital that may be utilized at a later time (Fredrickson 2001).

This suggests that trait measures of happiness (particularly positive emotions) could predict long-term productivity, even if happy states were unrelated or even negatively related to short-term productivity. Although positive emotions likely foster productivity under many conditions, this effect is probably not ubiquitous. That is, just as pleasant emotions bias cognition and behaviour in some ways (fostering creativity and sociability), unpleasant emotions bias cognition and behaviour in other ways that may be useful under some circumstances. For example, negative moods seem to bias people’s attention towards details rather than global meaning (Gasper and Clore, 2002), improving task productivity when a detailed level of analysis is required. Complicating things further, the valence of moods may interact with people’s motivations or instructions.

For example, Martin et al. (1993) showed that positive moods predicted persistence when people were told to work until they felt like stopping, whereas negative moods predicted persistence when people were told to work until they could do no more. Even these interactive effects may further depend on the person’s accountability (Sanna et al. 1996). In sum, particular sets of emotions, motivations, personalities and tasks will combine in very complex ways to predict productivity. However, across the various tasks typically required of employees, happiness will, on balance, likely benefit overall productivity (Zelenski, et. al., 2008). Building upon prior research establishing main effect associations among job satisfaction, employee subjective well-being, and job productivity, the broaden-and-build model suggests that satisfied and psychologically well employees are more likely than those less satisfied and psychologically well to have the resources necessary to foster and facilitate increased levels of job productivity (Angner, et. al., 2011; Benrazavi and Silong, 2013).

Research has clearly demonstrated that positive feelings can help enhance one’s ability to be a better problem solver, decision maker, and evaluator/processor of events. In turn, research has consistently shown that these skills and abilities are related to job productivity. As an added bonus, these effects would appear to persist over time due, in part, to the differential manner in which happy and unhappy people recall events. In fact, as a general consequence, a continued focus on positive feelings expands or broadens and builds upon these positive urges, creating a potentially “upward spiral” effect, which is proposed to further enhance individual character development. This capacity to constructively experience positive feelings has been proposed to be a fundamental human strength (Al-Qaiwani, 2017).

Based on the Theory Y, as indicated by Hosie, Sevastos, and Cooper (2007), “few conundrums have captured and held the imagination of organisational researchers and practitioners as the happy worker-productivity association“. It is thought that happy people are more productivity (Diener, 2000) and this is the main assumption of this association, considered the best reference of management research (Wright, Cropanzano, & Bonett, 2007). It is assumed that, in equal conditions, “happy” workers should have better performance than “less happy” ones (Cropanzano & Wright, 2001; Wright, et al., 2007.) This association has produced a series of studies (Baptiste, 2008; Schulte and Vainio, 2010; Taris et al., 2009), however, the results are ambiguous and inconclusive (Wright & Cropanzano, 2000; Wright et al., 2007). Four limitations of these studies should be noted that explain in part the ambiguity of the results found:

- a focus on hedonic constructs of happiness,

- little attention paid to the “other aspect “ job performance,”

- bias, due to placing more attention on the results that confirm this association and paying little attention to “anomalous” ones, and

- revisits of this association that do not consider its expansion to the eudemonic constructs of wellbeing.

Thus, happiness has been studied as a state (Wright & Staw, 1999; Hosie, Sevastos, & Cooper, 2007) and as a trait (Hosie & Sevastos, 2009; Wright et al., 2002). In both cases, the results have been mixed. Secondly, there has been little attention to the operationalisation of performance, with very heterogamous measures such as the facilitation of work, the emphasis on goals, support and team building (Wright, Cropanzano, Denney, & Moline, 2002) the overall performance appraisal by the supervisor (Wright & Cropanzano, 2000), customer satisfaction, financial productivity, personnel costs and organisational efficiency (Taris & Schreurs, 2009). Several authors suggest defining job performance based on broader theoretical frameworks such as that proposed by Koopmans et al., (2011), with the aim of mitigating error sources, and in an attempt to find relationships between performance and satisfaction at work (Hosie & Sevastos, 2009). Thirdly, I find a bias towards exploring particularly the “bright” side of this association (happy and productivity), disregarding the “dark” side (unhappy and

unproductive, happy and unproductive or unhappy and productivity) and its impact for organisations or individuals. For example, recently difficulty remembering information and poor task performance have been associated as negative consequences of being “happy” at work (Baron, Hmieleski, Henry, 2012), and there have also been studies on the benefits of negative affect on creative performance (Bledow, Rosing, & Frese, 2013).

Instilling Culture of Happiness Among the Uae Society

Culturally, the UAE society has a collectivist culture where the interest of the group supersedes that of the individual (Suliman and Moradkhan, 2013). Knowing how a particular culture functions is imperative on instilling the happiness in to such culture. In UAE culture, modes of communication tend to be social, informal and unlike those in individualistic societies, the boundaries between leaders and their followers can be thin (Alrahoomi, 2014). In this Arab country, the Majlis culture is dominant where a political or social figure organizes an informal gathering between decision makers and ordinary citizens to deliberate and find solutions to people’s problems.

An old Arabic version of town-home meeting, Majlis allows citizens to attend the open sessions without prior scheduling or registration (Alshamsi, 2014; Alrahoomi, 2014). All Majlais (plural of Majlis) operate in parallel with the formal institutions of the government but without the legal authorities granted by the law. The status of those in power (leaders) in UAE society is dependent on their success in serving, helping, and keeping close ties with the led (follower) (Yaghi and Antwi-Boateng, 2015). The literature suggests that the values and norms of the traditional society heavily influence the organisational culture within public agencies and particular the informal patterns of communication between leaders and followers (managers and employees, respectively) (Yaghi and Yaghi, 2014). Organisationally, employees respect and obey those in power despite the informality of relationships and communication between the two parties (Yaghi, 2014).

Researchers found that Arab managers develop leadership styles depending on their belief that followers must show obedience and loyalty in exchange of good salaries and continuity of employment contracts (Alrahoomi, 2014). This exchange, a rational behaviour, imposes a necessity for managers to adapt with the changing organisational environment while maintaining relevance to local cultural norms. Shahin and Wright (2004) assert that conservative societies, as those of UAE, perceive such exchange (transaction) between followers and leaders legitimate because it facilitates employees’ adaptation while maintaining a certain level of stability in the society. In other words, the contract between managers and followers stabilizes the workplace and reduces tension, ambiguity, and resistance of change (Sheikh Mohammed Bin Rashid Al Maktoum, 2017; Almazroei, 2014).

Taking Smart Dubai as an example of this proposal, the vision for Dubai is to become the ‘Happiest City on Earth’, as outlined by H.H Sheikh Mohammed Bin Rashid Al Maktoum, Vice-President and Prime Minister of UAE, and Ruler of Dubai. This vision is undoubtedly noble, with many technical, social and psychological challenges (Sheikh Mohammed Bin Rashid Al Maktoum, 2017). This proposal outlines the official strategy, and the mechanisms employed to reach this vision, long with the technological and psychological tools used to ensure success, describing some actions taken to overcome such challenges, and data showing progress towards this vision. The strategy opted for by the city’s government is to focus efforts on transformation towards a world-class smart city, where Smart Dubai Office, led by H.E. Dr Aisha bin Bishr as Director General, is leading the orchestration of this transformation.

Smart technologies are seen as enablers towards the goal of happiness. However, such a strategy also needs to be grounded in clear definitions, frameworks and activities, where excelling in their practice would eventually lead to the vision outlined above. A primary step in this endeavour is to deal with the definition of ‘happiness’. However, though at first this may seem challenging, with various philosophical and psychological theories, some dating back to ancient philosophers, this may be overcome by focusing on the wellness literature, and turning instead towards fulfilling the needs of city residents in such ways as to facilitate happiness (Sheikh Mohammed Bin Rashid Al Maktoum, 2017). Starting with spiritual and emotional well-being (SWB), it is equated to the sum of (A) Affective and (C) Cognitive needs though this equation ignores (B) Basic needs that address the prosaic aspects of life in the city, as well as the (D) Deeper and more profound eudemonic needs, which are more about higher meaning and purpose. The model also includes (E) Enabling needs: internal (personal) and external (environmental). The internal enablers are about the personal skills and attitudes a person has, such as optimism and mindfulness, as well as their personality traits, such as openness and extraversion.

The external enablers are about the environment around them, including physical like natural environment as well as social aspects such as fairness and trust. This view forms the basis of Smart Dubai Office’s (SDO) ABCDE model of needs. SDO, therefore, aims to increase ‘happiness’ by satisfying and facilitating these needs towards a more complete and holistic positive experience in the emirate. The mechanism for fulfilling these needs is the Happiness Agenda, which aims to systematically address the needs of customers and increase happiness in a structured and methodical way. The Agenda has been designed to be fully aligned with the City Transformation Agenda, with its three impact axes: customer, financial and resources. The Happiness Agenda is composed of four portfolios: discover, change, educate and measure (Sheikh Mohammed Bin Rashid Al Maktoum, 2017).

Each portfolio is composed of programmes that are focused on achieving the strategic objectives of the portfolio, with each programme having a variety of specific projects to be executed. The projects within these portfolios are designed to find needs, create changes and interventions, create awareness so that other stakeholders may contribute to fixing issues proactively and innovate towards ‘happiness’ by satisfying these needs. In this way, psychological techniques and measures, combined with smart technologies, are used as the tools within the Happiness Agenda (Sheikh Mohammed Bin Rashid Al Maktoum, 2017).

Happiness and the Uae Workers

Therefore, one can argue that managers while leading organisational change, they may find it impractical to stick with one form or style of leadership in the UAE organisations. Instead, they may find a mixed style better useful and efficient in order to make the transition of their organisations smooth. Good feelings were most often experienced in connection with events involving achievement, recognition, interesting and challenging work, responsibility, and advancement or growth among the UAE workers (Sheikh Mohammed Bin Rashid Al Maktoum, 2017). This conclusion has been roundly criticized when referring to stable overall job attitudes, but does seem to have merit when describing the connection between momentary events and concurrent positive and negative emotions at work, consistent with current two-domain theories of the sources of affect.

More recent studies of events that cause positive emotions at work confirm that events involving goal achievement, recognition, challenging and interesting tasks, and pleasant interactions with others are associated with concurrent pleasant emotions, and that events perceived as hassles which because negative feelings do tend to be different from the mere absence of events perceived as uplifts. Perceived performance is likely to be another determinant of momentary positive mood and emotions at work (Snow, 2013). Employees spend most of their work time performing or attempting to perform, so beliefs about how well they are doing it should be both salient and continuously available. We know that goal achievement and positive feedback predict satisfaction. Control theory suggests that the rate of progress towards a goal is a determinant of positive affect. It is argued that perceived performance is a strong determinant of concurrent mood and emotion at work, especially for individuals who care about their job and who have adopted approach goals.

Finally, an individual’s momentary affect at work may be influenced by other people with whom he or she interacts through emotional contagion. There is evidence that contagion may occur from leader to follower. It is important to remember that happiness and positive attitudes are not directly created by environments or events such as those described above, but rather by individuals’ perceptions, interpretations and appraisals of those environments and events. The large body of research on appraisal theories of emotion.

Nonetheless, in the Middle East region, there is relatively little research on how individuals may volitionally contribute to their own happiness at work, though much of the advice on how to improve happiness in general (practice gratitude, pursue intrinsic goals, nurture relationships, find flow) could also be applied in the work setting. Momentary happiness is associated with perceptions of effective performance or progress towards goals, so setting and pursuing challenging but achievable short-term goals may enhance real-time feelings of happiness. At the more stable person-level, individuals could seek both person–job and person–organisation fit when choosing employment and adjust expectations to match reality. If dissatisfied, they might decide to leave one job and find another that suits them better, though very few studies have investigated this phenomenon by following individuals across organisations. It has been suggested that individuals will be more authentically happy if they feel a ‘calling’ or a connection between what they do at work and a higher purpose or important value.

Individuals are thought to craft their jobs to assert control, create a positive self-image at work, and fulfil basic needs for connection to others. For instance, nurses may redefine their work as helping patients heal as opposed to performing menial tasks as directed by physicians. Such changes should be quite effective in creating both supplementary and needs supplies fit, and would be expected to improve happiness at work. Another approach for individuals to improve demands–abilities fit is provided by the strengths based view. This approach suggests that each individual has a unique configuration of personal or character strengths, talents, and preferences. Individuals should discover what their personal strengths are, and then design their job or career to allow them to cultivate these strengths and spend much of each day applying them while minimizing demands to complete activities that do not use strengths. Following this advice should improve both eudemonic and hedonic happiness, as individuals enjoy greater competence and self-actualization (Tadic, et. al., 2013).

Perceptions of a number of attributes of organisations and jobs are reliably correlated with job satisfaction and affective commitment, suggesting that these attributes might be levers for organisations wishing to improve happiness in the workplace (Tenney, et. al., 2016). Specific, if idealistic, suggestions include the following:

- Create a healthy, respectful and supportive organisational culture.

- Supply competent leadership at all levels.

- Provide fair treatment, security and recognition.

- Design jobs to be interesting, challenging, autonomous, and rich in feedback.

- Facilitate skill development to improve competence and allow growth.

- Select for person–organisation and person–job fit.

- Enhance fit through the use of realistic job previews and socialization practices.

- Reduce minor hassles and increase daily uplifts.

- Persuade employees to reframe a current less than ideal work environment as acceptable

- Adopt high performance work practices

Unfortunately, disposition also affects happiness in general and at work, such that happiness may be somewhat ‘sticky’ and less than perfectly responsive to improvements in objective organisation and job features. Further, the fact that individuals bring different needs, preferences and expectations to work suggests that no single solution will make everyone equally happy. A reasonable question to ask is whether organisations and individuals should in fact try to improve employee happiness at work.

Context of Happiness at Workplace

A positive feeling such as happiness has always been appreciated throughout history. According to Aristotle, the lowest levels of happiness is hedonism and for want of a better word, pleasure. In the moderate level, happiness equals success and achievement and in the highest level, happiness is achieved through spirituality (Eysenck, 1990). Put it another way, Aristotle considers happiness as spiritual life and Plato regards that as a balanced state between three elements of wisdom, emotion and desires. Our research sheds a brighter light on this very specific notion because it’s believed that, psychology is the sciences of living happily. Psychologists’ efforts throughout the worlds are to identify the barriers of happiness, alleviate emotional pains and devise methods thereby; individuals can adapt themselves to life. Psychologists intend to explore the rules of living better so that, the human can predict himself/herself better and once this is attained; s/he will be able enough for controlling and inhibiting while necessary. If the human cannot get to know the accurate rules of life, she cannot declare having a happy life.

Meanwhile spiritual and emotional well-being focuses on positive psychology which has tried to devote attention to humans’ abilities. This science is currently known as having done comprehensive studies for wellnessand happiness in different educational, hygienic, therapeutic and academic realms (Linley, 2004). Positive psychology is known as a movement for directing individuals toward growth and actualization and does not intend to be replaced with any of the other psychological therapies (Seligman, 1990).

Scientific society has recently documented evidences for the conceptualization of different aspects of positive psychology, particularly well-being. Following from Warr (1990) wellbeing tends to be a broader concept that takes into consideration the “whole person”. Beyond specific physical or psychological symptoms related to health, wellbeing should be used as appropriate to include context-free measures of life experiences (life satisfaction, happiness), and within the organisational research to include job-related experiences (job satisfaction, job attachment), as well as more facet specific dimensions. Wellness can refer to mental, psychological, or emotional aspects of workers.

Being happy is of great importance to most people, and happiness has been found to be a highly valued goal in most societies. Happiness, in the form of joy, appears in every typology of ‘basic’ human emotions. Feeling happy is fundamental to human experience, and most people are at least mildly happy much of the time. This review is aimed at happiness at work. Organisational researchers have been inspired by the move towards positive psychology in general, and have begun to pursue positive organisational scholarship and positive organisational behaviour, though there is still debate on exactly what these terms encompass and how helpful they might be.

The largest divide is between hedonic views of happiness as pleasant feelings and favourable judgments vs eudemonic views of happiness involving doing what is virtuous, morally right, true to one’s self, meaningful or growth producing (Michaelson, et. al., 2014). The hedonic approach is exemplified by research on subjective well-being. Spiritual and emotional well-being is usually seen as having two correlated components: judgments of life satisfaction (assessed globally as well as in specific domains such as relationships, health, work, and leisure), and affect balance, or having a preponderance of positive feelings and relatively few or rare negative feelings (Wright, et. al., 2007).

In contrast to the hedonic view of happiness as involving pleasant feelings and judgments of satisfaction, eudemonic well-being, self-validation, self-actualization and related concepts suggest that a happy or ‘good’ life involves doing what is right and virtuous, growing, pursing important or self concordant goals, and using and developing one’s skills and talents, regardless of how one may actually feel at any point in time (Bhattacharjee and Bhattacharjee, 2010). With rare exceptions, happiness is not a term that has been extensively used in academic research on employee experiences in organisations. This does not mean that organisational researchers are uninterested in employee happiness at work. On the contrary, for many years we have studied a number of constructs that appear to have considerable overlap with the broad concept of happiness (Hoboubi, et. al., 2017; Fisher, 2010).

First is the level at which they are seen to exist, second is their duration or stability over time, and third is their specific content. The Affective Events Theory draws the attention of researchers to real time affective work events and the short-lived moods and emotions that individuals might experience as a result (Paul and Guilbert, 2013). Happiness-related constructs which are usually defined and measured as transient states that vary at the within-person level include state positive mood, the experience of flow, and discrete emotions such as joy, pleasure, happiness, and contentment. Example research questions asked at the transient (within person) level might be ‘Why is an employee sometimes in a better mood than usual for him or her?’ ‘Why does an individual sometimes experience a state of flow and sometimes not?’ and ‘Do individuals sleep better after days during which they’ve experience more positive affect than usual at work?’ (Joo, et. al., 2017; Fisher, 2010).

Happy employees are 12% more productivity and companies with happy employees outperform the competition by 20%. Happy employees are typically the ones who care about the organisation and have a desire to help your company achieve success. 67% of full-time employees with access to free food at work are “extremely” or “very” happy at their current job. Meanwhile close work friendships boost employee satisfaction by 50% as while employee happiness and engagement are not the same thing, they are generally correlated. It is pretty rare to see someone who loves walking into the office each day but finds no value or purpose in their work. Also, the top three factors contributing to job satisfaction are job security, opportunities to use skills and abilities and organisation’s financial stability. Thus, happy employees have a positive impact on the bottom-line. Having happy employees is insanely important for the health of your organisation. Happier teams work harder, are more productivity, and work better together (Shour, 2016).

Most happiness constructs in organisations are conceptualized at the person level, where all the variance of interest occurs between individuals. The vast majority of research in organisational behaviour has focused on this level, and it appears to be our default mode of thinking. It opens with the person-level question, ‘Why are some people at work happier or unhappier than others?’ Happiness-related constructs usually defined and measured at person level include dispositional affectivity, job satisfaction, affective commitment, and typical mood at work. Then, the unit-level constructs describe the happiness of collectives such as teams, work units, or organisations. Virtually all measures of these constructs are based on reports of individual members of the collective, with one of two different types of referents. In the first, the person’s own experience is the referent, and group-level constructs are created by aggregating the personal experiences or traits of individuals in the collective. For instance, group affective tone has been operationalized as the average of team members’ ratings of their own affect during the past week. The second approach causes and aggregates individuals’ perceptions of the collective as the referent (Paul and Guilbert, 2013; Fisher (2010).

Depending on the theory involved, either individual referent or group referent measures of collective happiness may make sense. Example research questions involving unit-level happiness constructs would be, ‘What are the effects of unit-level engagement on unit-level customer satisfaction?’ ‘What is the effect of team mood on individual mood and performance?’ and ‘Does group task satisfaction contribute to the prediction of group-level citizenship behaviour above and beyond the effects of aggregated individual job satisfaction?’ The content of happiness constructs and measures varies considerably, though all feature a common core of pleasantness. There are a great many existing constructs that have something to do with happiness at work, be it fleeting and within person, stable and person level, or collective (Hoboubi, et. al., 2017; Bhattacharjee and Bhattacharjee, 2010).

Certainly, these three levels are different from each other, require their own measures, and would typically be used to predict criteria at different levels. The largest proliferation of constructs and measures is at the stable person level. If happiness at this level is viewed as the proverbial elephant being examined by blind men, we can conclude that we have developed a good if isolated understanding of its parts, such as the trunk (job satisfaction) and the tail (typical mood at work). It may be that we have decomposed the beast into almost meaninglessly small pieces (the right ear of vigour, the left ear of thriving). Perhaps what is missing is a more holistic appreciation of the entire animal in the form of happiness at work. Researcher knows that broad constructs perform better in predicting the broad criteria often of most interest to organisational researchers. One might wonder which happiness related measures are broad enough to have predictive utility and to cover collectively the territory of happiness at work at the person level.

Researcher’s suggestion is to distinguish three foci or targets for happy feelings:

- the work itself;

- the job including contextual features; and

- the organisation as a whole.

The three parallel broadband measures most likely to be useful in this framework would be

- engagement, representing affective and cognitive involvement and enjoyment of the work itself;

- job satisfaction, representing largely cognitive judgments about the job, including facets such as pay, co-workers, supervisor and work environment; and

- affective organisational commitment, as feelings of attachment, belonging and value match to the larger organisation.

These three measures together should capture much of the variance in person-level happiness in organisations. The next section of this paper turns to a consideration of what causes individuals to feel happy, first in general, and then specifically in organisations (Hoboubi, et. al., 2017).

Constructs of Happiness at Workplace

For much of the history of organisational behaviour, most assumed that the dominant causes of happiness or unhappiness and stress in organisations were to be found in attributes of the organisation, the job, the supervisor, or other aspects of the work environment. A very great deal of literature has accumulated showing which aspects of organisations and jobs are most often predictive of job satisfaction, organisational commitment, and other forms of happiness at work (Weimann, et. al., 2015). At the organisational level, one might consider attributes of the organisation’s culture and human resource practices as likely causes of happiness among organisation members (Fisher, 2010). The Great Place to Work Institute suggests that employees are happy when they ‘trust the people they work for, have pride in what they do, and enjoy the people they work with’. Trust in the employer, built on credibility, respect, and fairness, is seen as the cornerstone.

It is agreeable that three factors are critical in producing a happy and enthusiastic workforce: equity (respectful and dignified treatment, fairness, security), achievement (pride in the company, empowerment, feedback, job challenge), and camaraderie with team mates (Michaelson, et. al., 2014). High performance work practices, also known as high involvement and high commitment approaches, involve redesigning work to be performed by autonomous teams, being highly selective in employment, offering job security, investing in training, sharing information and power with employees, adopting flat organisation structures, and rewarding based on organisational performance. These practices often improve motivation and quality, reduce employee turnover, and contribute to short- and long-term financial performance. High performance work practices also seem likely to enhance affective commitment, engagement, and satisfaction, and in fact some of the impact of these practices on organisational performance may be mediated by their effects on employee happiness (Paul and Guilbert, 2013).

High performance work practices may act on happiness at least partly by increasing the opportunity for employees to attain frequent satisfaction of the three basic human needs posited by Self-Determination Theory (competence, autonomy, and relatedness) (Hosie, et. al., 2012). Research on perceived psychological climate provides evidence that individual-level perceptions of affective, cognitive, and instrumental aspects of organisational climate are consistently and strongly related to happiness in the form of job satisfaction and organisational commitment. Another meta-analysis showed that five climate dimensions of role, job, leader, work group, and organisation were consistently related to job satisfaction and other job attitudes (Joo, et. al., 2017). Exceptions of organisational justice are also related to job satisfaction and organisational commitment. In sum, it appears that some aspects of organisational practices and qualities, and how they are perceived by organisation members, are consistently predictive of happiness-related attitudes. The next section considers job-level influences on happiness at work (Miller and Miller, 2016; Fisher, 2010).

Much of the research on what makes people happy in organisations has focused on stable properties of the job, with complex, challenging, and interesting work assumed to produce positive work attitudes (Rotaru, 2014). The best-known typology of job characteristics is with evidence confirming that jobs possessing more of these characteristics are more satisfying to incumbents. It could have expanded the conceptualization of job characteristics to include not just the five motivational factors but several additional motivational factors, social factors, and work context factors, meta-analysis showed that most of these are positively related to happiness at work, and collectively explain more than half of the variance in job satisfaction and the variance in organisational commitment (Quinlan, 2012). Another typology of job characteristics that goes beyond the work itself to include supervision, pay, and career issues as additional predictors of happiness. Generally, greater quantities of desirable job characteristics are considered better.

However, it is also suggested that, like some vitamins, increasing amounts of some job characteristics improve wellbeing only until deficiencies are overcome and one reaches the recommended daily allowance. Beyond that point, additional amounts are thought to have limited beneficial effects on happiness. Further, there may be some job characteristics that in high quantities actually reduce happiness, just as it is possible to overdose on some vitamins (Samnani and Singh, 2014). For instance, it is possible to have too much personal control, too much variety, and too much clarity. Moving away from the work itself to consider other job-level attributes, there is evidence that leader behaviour is related to employee happiness. A final source of happiness at work may be pleasant relationships with other people. Aside from research on leadership, social connections at work have been largely ignored by researchers. This is surprising, given the absolutely central role that interpersonal relationships are known to play in human happiness and well-being. Recently, interpersonal relationships in the workplace have begun to attract some attention, and it appears that ‘high quality connections’ with others may be important sources of happiness and energy for employees (Hosie, et. al., 2012).

As the above paragraphs have focused on the effects of relatively stable aspects of the work setting such as organisational practices and job design on similarly stable measures of happiness such as overall job satisfaction (Michaelson, et. al., 2014). The Affective Events Theory suggests that stable features of the work setting such as those described above act at least partly by predisposing the more frequent occurrence of particular kinds of affective events momentary happenings that provoke concurrent moods or emotions. For instance, one might expect that enriched jobs would more often provide events involving positive feedback or challenges successfully met, either of which should create concurrent positive affect. As predicted by The Affective Events Theory, the cumulation of momentary pleasant experiences has been shown to predict overall job satisfaction. The effects of momentary states of happiness are largely positive. At the day level, state positive mood is associated with creativity and proactivity on the same day and predicts creativity and proactivity the next day.

Positive mood also seems to reduce interpersonal conflict and enhance collaborative negotiation outcomes. Day-level fluctuations in positive mood and job satisfaction predict daily variance in organisational citizenship and workplace deviance at the within-person level. Momentary positive mood can also influence how other aspects of the work environment are evaluated, with induced pleasant moods spreading to concurrent ratings of job satisfaction and task characteristics. Momentary moods are also implicated in motivational processes. These facts might manipulate state mood and found that positive affect increased persistence and task performance, and acted on motivation by increasing expectancies, instrumentalities and valences. While the most common effect of momentary happiness on work behaviour appears to be positive, it has been argued that moods and emotions can harm concurrent work performance (Samnani and Singh, 2014).

Warr (2007) and Fisher (2010) emphasize three principal domains of happiness, namely context-free or a person’s chronic state of happiness (see Hellen & Sääksjärvi, 2011) domain-specific happiness covering only feelings in a targeted domain such as happiness at home with family members, happiness at work, and facet-specific happiness focusing on particular aspects of a domain, such as our pay, physical surroundings at work, or supervisor. Many publications appear to be based on the assumption that causes and consequences are the same at each level of scope. They are not, and must be distinguished from each other (Warr, 2007, p. 726). The study here focuses on the relationships of the demographic influences on service-facet happiness, overall happiness, and on-the-job performances, and the second and third domains of happiness. Thus, employee happiness is also built based on its constructs such as performance appraisal, flexible working hours, promotion, rewards and recognition, income, peers and supervisors support, and workload.

- Performance Appraisal

Campbell (2013) stated performance appraisal is an essential instrument of personnel management designed to identify an individual employee’s current level of job performance, identify employee strengths and weaknesses, enable employee improve their performance, provide a basis for rewarding or penalizing employee in relation to the contribution or lack of adequate contribution to corporate goals, motivate higher performance, identify training and development needs, identify potential performance, provide information for succession planning, validate selection process and training, encourage supervisory understanding of the subordinates. According to Oniye (2015) appraisal results provides vital information about a workers strength and weaknesses, training needs and reward plans such as advancement, promotion, pay increase, demotion and work or performance improvement plans. Performance appraisals have the equal probability of having a bad impact on the organisation as well as employee performance (Escott & Buckner, 2013). It is also known as a formal program in which employees are told the employer’s expectations. Performance appraisers are used to support the decisions including promotions, terminations, training and merit pay increases (Silla, De Cuyper, Gracia, Peiró, & De Witte, 2009). It is an employer’s way of telling employees what is expected of them in their jobs and how well are meeting those expectations. Performance appraisal which is seen as a way of providing review and evaluation of an individual job performance has its own negative and positive effect on the employee’s productivity in an organisation (Berger, 2009). This system acts as a motivator to the employee to improve their productivity. When the goals of the employee are clarified, his performance challenges identified, the effect is to motivate the employee to achieve those goals. Performance appraisals usually have a positive and negative impact on employees. Positive feedback on appraisal gives employee a feeling of worth and value especially when accompanied by salary increment. If a supervisory gives employee a poor score on his/her appraisal, the employee may feel a loss of motivation in the workplace (Jiang et al., 2012; Oniye, 2015). This has an impact on the employee performance as based on Rudman (2003), performance appraisal policy is a critical factor in an organisation in enhancing the productivity of the employees (Foroutan, 2011; Schraeder, Becton and Portis, 2007). - Income (wage, salary and bonus)

Income includes the wage, salary and bonus income earned by an individual (Mathur, 2012). A study of income and happiness by Caporale, Georgellis, Tsitsianis and Yin (2009) confirms that there is a strong relationship between a person’s income and life satisfaction. This is because people who have higher income have more opportunities to buy desired goods and services (Frey & Stutzer, 2002; Schnittker, 2008). Even though people who gain higher income seem to be happier people, their happiness level is affected by working hours. People may be unsatisfied with their jobs if they have long working hours (Georgellis, Lange, & Tabvuma, 2012).

Furthermore, people compare their own income with others (Lembregts & Pandelaere, 2014; Oshio & Kobayashi, 2011). They are likely to be happy when they perceive income equality (De Prycker, 2010). Oshio and Kobayashi (2011) contend that individuals who experience income inequality are less happy. In contrast, Hopkins (2008) argues that income inequality can positively affect employee happiness of some competitive people who gain more income than others. This is because competitive people try to make the difference between their own and others’ rewards (Brody, 2010). They may be happy with higher income even if it is unequal to those people (Hopkins, 2008). - Flexible Working Hours

The definition of Flexibility/ Flexible Working Hours is not uniform and is itself a matter of debate. The terms Flexible Working Hours (FWH), Flexibility, and Flexible Working Arrangements (FWA) have been quite often used interchangeably. The concept may be viewed as a multidimensional in nature. For example, the various things which have to be taken into account, while defining this concept maybe the kind of work, social organisation, individual parameters etc. The concept of flexibility may encompass a different combination of quantitative and qualitative variables. Past researches have broadly presented these variables as a) numerical flexibility (e.g. work on demand), b) geographical flexibility (outsourcing), c) functional flexibility (job enrichment), and d) temporal flexibility (night and shift work, part-time, overtime,). But from technical point of view the FHW practice includes a variety of options which include part-time, shift swapping, sabbaticals, self-rostering, homeworking, job share, term-time working, compressed week, time off in lieu, flexitime, annualized hours, overtime, sub-contracting, zero hours contracts, mobile working, and hot-desking. One of the important outcomes that organisations can expect after bringing FWH in the scheme of things is that it can sort out the Work Life Balance (WLB) issues related to employees. Some of the researchers have presented linkage between FHW and WLB in recent past. Among various dimensions of WLB employee well being seems to be the most important factor affected by the change in working conditions and environment. Using a method of expert commentary Kossek, Kalliath and Kalliath (2012) have elucidated the utmost importance of work environment in relevance to employee well being. Consequently, the subtle changes in work environment would also include inducing some element of flexibility in the timings or place of work as such. Thomson (2008) has also conceptualized improved WLB as a positive outcome of FWH. With the help of some case studies the author has highlighted the importance of FWH in transforming a failing department into a productivity one within shorter period of time. This study also puts forward a strategic framework for implementation of FWH. The framework suggests that in order to make any FWH program a success, the organisation must be very clear as what they actually want to achieve. To ensure this they need set very clear objectives related to FWH and those objectives must be aligned with corporate strategic goals, the implementation must be done in accordance with the available resources and more importantly the said changes need to be communicated effectively. In other words it can be said that the decisions related to FWA need to taken at strategic level. Linking flexible working practice with happiness Atkinson and Hall (2011) have demonstrated that there is perception among the employees that flexible working makes them happy. The authors also recommend that this happiness ultimately leads to better performance outcomes and employee retention. The critical observation of the above mentioned studies clearly indicates that Flexible Working Hours/ Flexibility in one or other way have impact on the organisational productivity and thus has great implications for all managers in general and HR managers in specific. The review of the relevant studies shows that FWH can increase the organisational productivity through various intervening factors if it is suitably implemented. The factors that seem to be mostly affected by FWH and have been researched to some extent are; Work Life Balance (WLB), organisational diversity, employee happiness, reduced stress, social inclusion, employee wellness and quality of life, employee productivity, cutting down recruitment costs, employee retention, motivated workforce and many more. All these factors have significant potential to boost the employee productivity (John, 2017). - Peer and Supervisor Support