Abstract

The latest financial crisis, which has brought about long-lasting consequences for the economy of the country, provoked heated debates about the possible reasons for another impending collapse. Experts are discussing the framework of global financial systems, their weaknesses, and the reliability of the regulatory mechanisms (Sunderam, 2014). Many agree that shadow banking—commonly defined as a non-bank diverse set of financial intermediaries collectively carrying out banking functions outside financial regulations—currently presents the greatest danger to the economy.

These institutions, usually poorly supervised and not following any capital requirements, account for more than a quarter of the international financial system—with assets amounting to $75 trillion—and are likely to increase in number in the near future (Gennaioli, Shleifer, & Vishny, 2013). This makes shadow banking a highly probable cause of the coming crisis, which already cannot be easily prevented by financial regulation only.

Introduction

The so-called shadow banking system, comprised of numerous institutions operating outside the regulated banking system, has undoubtedly contributed greatly to the emergence of the latest global financial crisis. This critical situation, which began in the form of market liquidity seizure as a result of growing default rates and devaluation of property, was gradually transformed into a global banking collapse, the consequences of which have still not been fully overcome by present-day economies (Sunderam, 2014).

The crisis undermined the existence of many financial institutions, which necessitated re-evaluation of key control principles. Financial architecture had to be examined closely to define what role the interaction of universal banks and non-bank institutions played in the dynamics of the crisis. The major question was whether shadow banking really triggered the collapse or rather fell victim to it alongside regular banks.

However, even a decade later, there is no agreement on the answer. It would be a simplification to state that the shadow banking system was the sole actor in this play. If the whole blame could be attributed to it, it would mean that tight regulation of the system would suffice to prevent a future crisis. Yet, experience proves that this strategy is not as efficient as it may seem (Kodres, 2013).

This leads analysts to the logical conclusion that the problem is much more complex and intricate than is commonly believed. Many other obscure financial bodies co-operating inside the shadow banking system may claim primacy in provoking the crisis. Still, it cannot be stated that the government was unaware of their existence. Therefore, it is not without reason that the system itself played mainly an amplifying role. In fact, there is no precise answer whether shadow banking was the root cause or only one of the agents of the crisis. What can be said for certain is that it led to the creation of collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) that played the most crucial role in crisis amplification. It means that the influence of shadow banking should not be overlooked (Prates & Farhi, 2015).

Thus, the paper at hand will analyze shadow banking in order to prove that due to the existence of numerous non-bank organizations such as hedge funds, mutual funds, insurance companies, etc., which authorities are unwilling to eliminate as they contribute significantly to the development of the economy, it will not be easy to strip the network of its shadow covering to ensure that another crisis will not take place in the near future. To achieve this, a comprehensive approach is required if it is to be at all possible to safeguard the global financial system this time.

The Shadow Banking System and its Core Participants

The shadow banking system did not appear overnight, shortly before the financial crisis broke out in 2007—it had been developing and gaining power for a considerable period of time, transforming into one of the most influential actors in the field. However, it was no earlier than 2007 when the network of non-bank organizations received its name and attracted the close attention of analysts. Before that critical moment, the sector was simply viewed as a system of credit intermediation that acted in parallel with regular banks and conducted similar operations (Kodres, 2013).

However, when the collapse occurred, it became clear that shadow banking stood apart from other entities operating outside the official banking system as the risk it posed to the system was incomparably higher. Since that time, the shadow banking sector has been understood to be unregulated off-bank intermediation covering activities that threaten financial stability through liquidity transformation, leverage, and credit risk transfer (Prates & Farhi, 2015).

In order to investigate the essence of the problem, it is necessary to clarify how the shadow banking system came to the foreground. In the classical model of banking, banks are supposed to grant loans using their own resources as well as those obtained from depositors. In addition, they can create deposits by granting credits and issue debts in order to enlarge their capital and continue to grant loans (Lysandrou & Nesvetailova, 2015).

Since the latter usually last longer than deposits or debts, the system could become vulnerable and might run a number of risks owing to time mismatching. This hazard necessitated the creation of organizations that could guarantee loans and control the system so that banks might be positive that they possess sufficient resources to face losses in the event of withdrawals of investments (Kodres, 2013).

However, during recent decades, three complementary, parallel processes began to develop, which led to the emergence of the shadow banking phenomenon. The first process concerned commercial banks. Taking into account their unstable position, they decided to create a competitive edge through increasing the amount of credit available, which could be achieved by moving some of the assets off the balance sheet.

The banks never had sufficient resources to meet the requirements set by the Basel Agreements; therefore, they reasonably decided to exchange their unpromising role of credit suppliers for a more beneficial one of resource mediators whose services should be generously paid for (Sunderam, 2014). As a result, the immediate connection with borrowers was cut off and the monitoring of the consequences ceased. At the same time, banks switched their attention to the control of investment funds. Moreover, they started to render asset management services, providing hedge and offering credit lines through various debt bonds.

Finally, a large number of organizations that performed the same roles as commercial banks emerged (Lysandrou & Nesvetailova, 2015). However, they were excluded from the regulatory structure and could not amass the necessary financial reserves. As a result of these processes, there appeared a shadow network that encompassed various organizations (independent investment banks, hedge funds, pension funds, private equity funds, insurance companies, etc.) that were connected with leverage loans and had no access to deposit insurance. Regional banks that provided mortgage credit as well as quasi-public agencies meant to create liquidity of the estate market can also be added to the list of agencies that are not subject to the Basel Agreements (Kodres, 2013).

Consequently, banks subject to regulations started to look for ways to mitigate credit risks. For this purpose, they submitted credits that they granted to agencies assessing risk, and they issued bonds or collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) with different risks and returns. The so-called “interest waterfall” was established; the analogy was built on the image of water gradually filling up one reservoir after another (Amoruso & Duchac, 2014).

Special investment vehicles (SIVs) were created to purchase structured bonds; however, their activity was not documented on the balance sheets, and they could not be regarded as banks’ property. These factors made them a significant part of the shadow banking network of financial intermediaries since they made it possible for regular banks to find sufficient resources to grant new credits (Chernenko & Sunderam, 2014).

Credit derivatives (CDs) were introduced and spread—this safeguarded the shadow banking network from any possible risks. To be on the safe side, financial organizations started to combine products using various instruments such as bonuses, mortgages, debentures, and others, regardless of the asset. Since SIVs could not raise resources from depositors, they decided to issue commercial papers (which amounted to $1.5 trillion in 2007); to stay in the credit market, they used short-term resources to fund long-term credits (e.g., selling protection against risks).

SIVs were far from the only institution to enter the shadow banking system. The most influential bodies included investment banks, hedge funds, pension funds, and insurance companies. Hedge funds were rapidly growing in number under the control of investment banks; moreover, they were also sponsored by universal banks that gave them credits for performing operations and even borrowed their banking strategies, which made them leverage their bets. Therefore, hedge funds gradually became the most influential actors in the system since their activity was not regulated, with the implication that they were capable of threatening the stability of the whole structure (Palan & Nesvetailova, 2014).

Risk-rating agencies constituted another force that aggravated the situation. With the appearance of the system, they started to increase in number and won huge profits by assisting financial bodies in mounting credit packages (Nesvetailova, 2014).

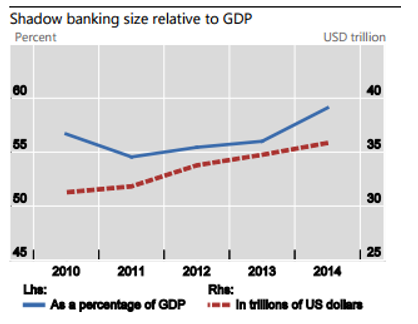

Thus, it is evident that the shadow baking system has grown exponentially since the moment it emerged (Figure 1), which led to the first global crisis and is likely to lead to the second. Moreover, its relation to GDP is also demostrative (Nesvetailova, 2014).

The given figure shows that the ratio of shadow banking to GDP has increased by 4% (from 55% up to 59%) within the period covering only two years (from 2012 to 2014). This steady growth has already outpaced GDP, which means that economists have all reasons to worry. The growth of the sector is usually associated with economic profits as the major reason the government supports shadow banking is the development of the economy that it triggers.

However, during the period covered by the given statistics, shadow banking institutions tended to grow much faster than GDP (which is shown by the dots located above the main line). This fast expansion of credit in relation to GDP threatens the economy with even a greater amount of systemic risk factors that the banking sector has to encounter. The tendency has been persistent during the recent years and now seems to be aggravating (Nesvetailova, 2014).

The system, with all its participants, continues to perform activities that are not covered by standard bank regulations, preserving its outsider status and making much larger profits than regular banks. Yet this underground network has already stepped outside the boundaries of what the market could have borne, and this has led to devastating consequences (Nesvetailova, 2015).

Current Threats

It would be logical to assume that the problems provoked by the shadow banking system should have led to the loss of its popularity and influence. However, according to the statistics provided by the Financial Stability Board, the size of the off-bank network has already exceeded $75 trillion (with $24 trillion belonging to the United States), which means that the system has tripled since the beginning of the crisis. It is still loosely regulated, mainly because governments do not want to lose the profit that once assisted economic growth, and this gives shadow banking institutions a power that no regular bank can enjoy (Nesvetailova, 2015).

In turn, the regular banking system continues to shift activities to shadow banking in order to evade tightened regulations imposed by the government; the investor is therefore separated from the investment, making it impossible to discern the real hazards that currently exist. This tension is exacerbated by a lack of transparency that makes the world economy vulnerable to the same factors that triggered the collapse of 2007–2008. Although the shadow banking system uses different approaches and makes other offers to its clients, the principle remains basically the same. For example, the so-called tranche opportunity is practically the same as CDOs (Plantin, 2014).

Thus, the problem is actually not in the system itself but in the government’s attitude toward the system. No one was going to eliminate off-bank organizations because of the potential of these assets to contribute to the financing of the present-day economy. The United States remains dominant in the shadow financial market, having more than 40% share (Sunderam, 2014).

Still, it does not mean that only the United States is at risk of replaying the same crisis as occurred ten years ago—the rapid expansion of shadow banking, encouraged by a number of governments, undermines the financial stability of the whole world. According to the International Monetary Fund, unless policies are introduced to regulate activities outside official banking, we will soon witness an unprecedented shift of traditional banking into the shadow—a process that could hardly be reversed. As a result of ultra-loose monetary policies, another catastrophe with even more deplorable consequences is likely to emerge.

The whole banking sector will become infected by entities that currently extend credit in the shadow. Nevertheless, the Fund recognizes the significant role of shadow institutions in expanding access to credit that was limited by regular channels (Sunderam, 2014).

The Fund claims that the stability of the global financial system is mostly threatened by a lack of normal regulation, which means that only increasing transparency and sharing information can strip the sector of its shadow. However, there is currently no sign to indicate that this is going to happen. On the contrary, the system has shifted to activities that are even less comprehensible and controllable than before, which makes all supervisors totally helpless, no matter how well they may perform their job.

Furthermore, the steps that are taken mostly lower standards for regular banks instead of providing a reasonable set of regulations for shadow banks, making the situation even worse. The idea of increasing network transparency is supported by the Financial Stability Board, which claims that stricter oversight is required to avoid another crisis (Nesvetailova, 2015).

In any event, the greatest problem is that the authorities are aware of the situation but do not seem to be willing to take steps to deal with it. They realize that new bank policies would create new challenges that would require time and effort to address. The biggest of these challenges is to come up with the kind of regulations that would allow shadow banks to hold enough liquidity to make them reasonably vulnerable to outer hazards. Even if the authorities find an adequate solution to this and devise a set of standards, it is still doubtful that regulators, who are limited in power and disposable resources, will succeed in a business in which investors and non-bank intermediaries have collectively failed (Nesvetailova, 2015).

However, if new requirements are added to the list, the capacity of the shadow banking system to continue introducing new hazardous and suspicious activities may be significantly restricted. Monitoring overall leverage is still necessary as credit ratings are unreliable if any hidden risks are present. The regulator’s scope of duty may also include tracking regular banks in order to find out how much they are exposed to shadow banking or innovations introduced by the system (Plantin, 2014).

However, no regulation is capable of solving the problem of its own capacity and scope of influence. Hypothetically, regulation is supposed to preserve a delicate balance between close supervision (actually implying harsh imposition of rules) and preservation of diversity (which can be achieved only by allowing organizations to introduce financial innovations). Unless this compromise is found, the loss of diversity will expose the system to substantial risk. It turns out that if the regulation is loose, the system is put in jeopardy; if it is too strict, the financial sector is likely to suffocate, which will have a negative impact on the economy, yet there is no in-between position to take (Plantin, 2014).

Besides the evident lack of normal regulation, the shadow banking system has to deal with another risk: Regular banks do not insure investors’ funds, which means that they literally have no support in the banking industry in the event of another collapse. In point of fact, it is quite clear that the system relies on the government, which bailed it out the previous time. As a result, shadow organizations have no real need to conduct their business carefully and fairly as they are in any event safeguarded from consequences by the state authorities.

This has a considerable impact on the quality of their operations. In turn, the government has no real motivation for performing a thorough analysis of threats involved in financial transactions of the non-bank sector as it may reveal that the network is operating while ignoring numerous quality standards of which the authorities are aware (Sunderam, 2014).

The major problem in this is that such risks quickly contaminate the regular financial system, which is greatly vulnerable to shocks experienced by its intermediaries. It would be a mistake to believe that shadow banking lies outside the traditional financial sector; on the contrary, the two systems overlap, interact (as discussed above), and exert reciprocal influence. The current situation makes the boundary between them fuzzy and arbitrary, indicating the close interconnectedness of the two (Prates & Farhi, 2015).

Another problem related to shadow banks is that the scale on which they operate is currently largely unnoticed or even concealed. Despite all real and potential hazards, it is now quite typical of the FSB to diminish the scope of the problem, making the network of non-bank organizations look smaller and less influential that it actually is.

For this reason, the system has managed to escape an adverse reaction on the part of the general public—the system members are disguised, being presented as high-tech disruptors; for example, one of the largest mortgage lenders in the country performs its activities exclusively online. In most cases, both the public and regulators are not interested in such companies as much as they are attracted by traditional organizations—this implies that the new systems manage to escape regulation merely because of being innovative platforms (Prates & Farhi, 2015).

Thus, the most worrying tendency concerning shadow banking is that the system has already consolidated itself as a global phenomenon. This means that a lot of countries approve of its activity and even encourage it, thereby undermining their financial systems. For example, in China, shadow banking has been rapidly gaining momentum, which leads to the conclusion that this will be a source of the crisis to come as regulatory arbitrage is happening in the country on a huge scale. Chinese banks are prohibited from lending to some businesses, making them perform their operations indirectly. The negative effects of this can still be tempered by official banking, but this will not last for long—a $75 trillion system is fine as long as markets continue to go up, but as soon as they start going down, there is a strong chance of collapse leading to international devastation (Li, 2014).

Among the most frequently cited precipitators of a future crisis of the system, financial experts usually name the following (Palan & Nesvetailova, 2014):

- a mistake made by the central bank that would bring about reduced bond prices;

- the Chinese expanding credit being a worrisome tendency;

- crisis of emerging markets;

- geopolitical threats and risks that multiply with the growing tension;

- the effect of a butterfly wing, which, according to the chaos theory, means that in a levered financial system, any seemingly insignificant change may result in a comprehensive destabilization of global financial markets.

As it is highly complicated and delicate, the system of non-bank organizations will not be able to survive in turbulent times if another crisis eventually emerges. This means that the only way to save it is not to allow the system to run wild; otherwise, the world will witness how governments will harvest the fruit of their own careless financial policies.

Present-Day Shadow Banking Policy

The idea of the impossibility of the right balance of regulation discussed above does not, however, imply that no regulation should be put in place at all. On the contrary, every effort should be made to achieve progress in this direction. What is actually emphasized is that shadow banking should not be seen as the root of all evil, especially when the government itself is not interested in its elimination.

Regulation alone will definitely not suffice; unless wider initiatives are proposed to target the operation of all the participants of the system, tight regulation will even exacerbate the situation as it would strangle financial innovations that support the diversity of the banking sector (Plantin, 2014). Since CDOs and SIVs responsible for the structural imbalance between the supply of debt securities and the demand for them have already been eliminated by the first crisis, the present-day system of regulation can only affect the ABS type of long-term securities. However, it can bring about a slowdown in the production rate, which will add to the current limitations put on the private sector securities, interfering with the ability to meet global demand (Prates & Farhi, 2015).

Other moves should be made toward resolving the bond market supply and demand disproportion. Otherwise, we will have to face the risk of a return to financial products of the kind that already provoked the first collapse, a scenario the financial world hardly wants to replay. A possibly effective solution to the problem of supply would be to foster EME countries to expand their capital markets. The idea is that this rate must be proportional to the rate of the average GDP growth. However, this would require the development of legal infrastructure, becoming a long-term policy that would be able to address the shortfall in global bond supplies. On the contrary, short-term problems should be solved through a reliance on advanced market economies to ensure security of operations (Nesvetailova, 2015).

Donald Trump is likely to loosen the regulation of the financial system, including the network of non-bank organizations, and opt for a free financial market. Unlike his major opponent in the election, Hillary Clinton (who insisted on close supervision of the sector), the new president is going to pull back on regulation across the banking system as he believes that this approach was implicated in the previous crisis. Moreover, Trump calls for regulators to be more transparent in their intentions and activities (Finkle, 2017).

Nevertheless, all international accords connected with the financial system are likely to be monitored as never before. This would be assigned to the Financial Stability Board that is currently responsible for tracking the growth of the non-bank sector (Finkle, 2017).

All told, all these policies may put the system back in the position it held before the first global crisis as there is nothing that would cause a financial analyst to expect a different result from following the same approach.

It is now difficult to predict what profits further development of the shadow banking systems may bring to investors, who are sure to try to use the situation to their benefit. The problem is that they all have their own time horizons and degrees of tolerance as well as propensity to taking risks: The current situation is hazardous but the stakes are high indeed. This may mean that investors will have to scrutinize financial statements of issuers to venture upon illiquid, long-term, and hazardous programs; there are still many of them who would opt for holding assets of short maturity and high liquidity made possible by banks from the shadow sector.

There are now a lot of American investors who shifted the focus of their attention to Chinese shadow banking as it promises quick returns. However, they must bear in mind that all undertakings can be fraught with consequences since the Chinese financial market is at risk of collapsing.

Conclusion

Taking into account all the threats presented by a free financial market, it would be reasonable to recommend strengthening the oversight and regulation of the sector without putting severe bans or limits on it. A lot of investigation is required to identify sustainable models that have been operating successfully inside the shadow banking sector. Such financing strategies should remain intact as they do not present any systemic risks. The idea is to support old and safe models while preventing the growth of new, suspicious activities aimed solely at bringing profit to their initiators. It is highly recommended to introduce incentives associated with securitization: This will give entities operating in the sector enough motivation to refrain from putting themselves and the whole system in jeopardy.

The process of collecting information to introduce new regulations to the system is only the first step. The ultimate goal is to transform shadow banking into a market-based activity having a set of standards it would have to meet (similar to regular banks). Furthermore, a more effective (yet more flexible) regulatory system is required to diversify the sources of financing and give investors a greater freedom of choice: They would be able to opt for a more rapid growth without having to take risks.

Last but not least, regulation of the shadow banking system would empower the government and increase the prestige of the new president if he is able to address financial stability issues that his predecessors failed to resolve. However, it is important to refrain from falling into extremes as the sector should not be forced to become a part of regular banking–this would deprive it of all the benefits it currently provides.

References

Amoruso, A. J., & Duchac, J. (2014). Special purpose entities and the shadow banking system: The backbone of the 2008 Financial Crisis. Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal, 18(2), 107-117.

Chernenko, S., & Sunderam, A. (2014). Frictions in shadow banking: Evidence from the lending behavior of money market mutual funds. Review of Financial Studies, 27(6), 1717-1750.

Finkle, V. (2017). Issue: Shadow banking short article: Trump likely to loosen reins on shadow banking. Sage Business Researcher. Web.

Gennaioli, N., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (2013). A model of shadow banking. The Journal of Finance, 68(4), 1331-1363.

Kodres, L. E. (2013). What is shadow banking. Finance and Development, 50(2), 42-43.

Li, T. (2014). Shadow banking in China: Expanding scale, evolving structure. Journal of Financial Economic Policy, 6(3), 198-211.

Lysandrou, P., & Nesvetailova, A. (2015). The role of shadow banking entities in the financial crisis: A disaggregated view. Review of International Political Economy, 22(2), 257-279.

Nesvetailova, A. (2014). The epoch of market based funding: Shadow banking. Global Labour Column, 187(1), 1-2.

Nesvetailova, A. (2015). A crisis of the overcrowded future: Shadow banking and the political economy of financial innovation. New Political Economy, 20(3), 431-453.

Palan, R., & Nesvetailova, A. (2014). Elsewhere, ideally nowhere: Shadow banking and offshore finance. Politik, 16(4), 26-34.

Plantin, G. (2014). Shadow banking and bank capital regulation. Review of Financial Studies, 28(1), 146-175.

Prates, D. M., & Farhi, M. (2015). The shadow banking system and the new phase of the money manager capitalism. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 37(4), 568-589.

Sunderam, A. (2014). Money creation and the shadow banking system. Review of Financial Studies, 28(4), 934-977.