Introduction

The US healthcare system is very complex. The lack of uniformity in the coverage policy determines its specificity in comparison with the systems of other developed countries. Whereas, the high cost of medical service is the object of the US population’s complaints the enormous healthcare spending is the focus of the government’s concern. Hence, the country’s public spending on the healthcare is one of the highest among all the members of OECD. About 17.7 percent of the US GDP is spent on the healthcare while an average representative of OECD spends only 9.3 percent on the similar sector. However, it seems that large expenses fail to provide high efficiency. According to the official data, 30 percent of American adults could not afford to have a health insurance in 2012 (The U.S. Health Care System: An International Perspective 2014). As a consequence, all the transformations of the US health care market are aimed at increasing the competition and, thus, reducing both the medication services’ cost and the public health care spending.

One should necessarily note that the uneven coverage in the health insurance system results in the negative impact on the healthcare market in general. Whereas some segments of the US healthcare system, such as educational and institutional markets, show high competition rate, other fields, such as health insurance sector, are oligopolistic. In other words, the competition within the insurance market is low that leads inevitably to the cost’s increase. Thus, the small number of health insurance companies in the USA enables their owners to determine prices that prevents the market from efficient allocation of resources (Mwachofi & Al-Assaf 2011). In order to implement the measures that will help to reduce the costs of the healthcare market, one needs to analyze the principal mechanisms that underpin the competition level in the relevant field.

Health Economic Analysis

Moral Hazard

The moral factor is one of the determinants of the healthcare services’ cost. Some specialists believe that this phenomenon is the result of the information asymmetry that exists in the patient-company relations (Mwachofi & Al-Assaf 2011). Thus, it is presumed, that an individual that has a healthcare insurance tends to use the relevant services more frequently, and, at the same time, pay less attention to the health preservation procedures. For example, a person that is protected by the insurance can take up some unhealthy habits like alcohol and smoking increasing, thereby, the possibility of the service’s overuse. Healthcare companies, in their turn, employ the measures to avoid potential money loss – they reduce the clients’ access to the particular medical services or introduce extra charges. The problem is that the following actions affect all the patients including both those who do not have a healthcare insurance and those who perform proper care about their health.

The following problem might be resolved on condition that healthcare companies do not try to predict the risks of the service’s overuse and give up the practice of deductibles’ implementation like it is done in Germany (The U.S. Health Care System: An International Perspective 2014). The sustainable and clearly put terms of the insurance will encourage more people to purchase it that will compensate the risks. However, the relevant measures require the government’s intervention.

Allocations and Provisions

The unreasonable performance of allocations and provisions in the healthcare system might also lead to considerable cost increase. Thus, the US government allocates huge amounts of money to the healthcare budget, but the services’ cost remains rather high. It might happen because of the irrational spread of the resources within the system. For example, the government might oblige the citizens to undergo unnecessary procedures and, at the same time, fail to provide them with the truly essential services.

In order to avoid this inefficient allocation, a reconsideration of the service list is required. Hence, the government is to perform the monitoring of the healthcare services that show best preventative results and include them on the insurance. On the contrary, those services that prove to be less requested or less effective can be excluded from the insurance coverage and paid independently by patients whenever they use them.

Asymmetric Information Which Leads to Adverse Selection

The asymmetry information that is present in the patient-market relations is another factor that affects the cost formation. Specialists point out two main types of asymmetry: between a doctor and a patient and between the former and a health insurance company (Mwachofi & Al-Assaf 2011).

The example of the first asymmetry might be illustrated by the case when a doctor takes an advantage of a patient’s ignorance and prescribes extra services in order to receive the benefit.

The second issue is an opposite case when a client tries to conceal his medical history from a health insurance company so that the latter remains unconscious of the potential risks. The company, in its turn, is aware of the adverse selection and the fact that initially unhealthy people are more likely to use their services. Thus, they raise the premium in an attempt to prevent the possible loss. As a consequence, high costs affect all the patients (Mwachofi & Al-Assaf 2011).

Statistics shows that the described adverse selection is highly harmful to the healthcare market (Mwachofi & Al-Assaf 2011). The possible resolution of the following problem implies the introduction of universal coverage that will oblige all the patients to buy a standard insurance.

Third Party Agents

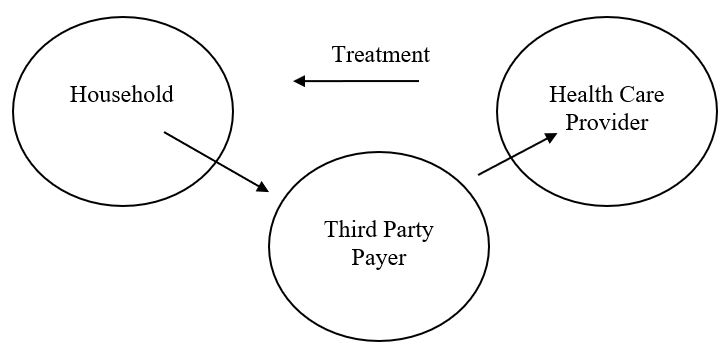

Apart from consumers and health care suppliers that essentially participate in the treatment process, there are also third party payers that play an important role in the cost formation (Morris, Devlin & Parkin 2007). Thus, the structure of the three agents’ interconnection might be represented by the following graph:

Therefore, the presence of a third agent prevents the supply and demand from being determined interdependently. One of the potential solutions is to reduce the determining power of the third party payer by implementing a universal coverage that will make the health insurance companies less dependable on the potential risks and less interested in the particular demand’s increase(Morris, Devlin & Parkin 2007).

Externalities

Externalities, or the “spill-over effects” as some specialists call them, can be of positive or negative character (Mwachofi & Al-Assaf 2011). One of the most typical examples of the positive externalities is the implementation of the vaccination practice. Thus, by vaccinating particular patients, one automatically prevents the rest of the society from getting infected. The negative externalities base on the similar principle. For example, the unhealthy habit of smoking is likely to have a negative effect not only on its owner but the people around him.

The major problem is that, whereas one is aware of the externalities phenomenon, there is still little possibility to consider all of them in the framework of the potential outcomes. Meanwhile, some specialists assume that the employment of the certain regulating tools might be an effective solution (Morris, Devlin & Parkin 2007). Such tools are supposed to encourage positive externalities on the one hand, and “punish” the negative ones. Therefore, the government can introduce the system of special subsidies and taxes (Mwachofi & Al-Assaf 2011). Whereas this measure will not help to eliminate the problem completely, it is still likely to be helpful for keeping the situation under control.

Market Power

It is presumed that the appearance of the market power is determined by the economies of scales factor. The increasing return to scales takes place in those cases where there is a large cost of the foundation of the service producer and a low cost of the services themselves. Thus, for example, the building of a large healthcare center requires a lot of expenses, whereas the costs of the service might turn to be relatively low. In other words, large companies tend to have more benefits than smaller firms. Therefore, it is advisable that the government encourages the creation of big healthcare organizations preferring them to a series of small companies (Mwachofi & Al-Assaf 2011).

Conclusion

The analysis of the US healthcare system has shown that whereas the country spends a large amount of its budget on the national healthcare, the cost of the service remains rather high and the system still has a number of serious drawbacks. First of all, it is necessary to point out the negative influence that the lack of coverage uniformity has on the general healthcare performance. Practice shows that the market conditions are not perfect; therefore, it fails to control the healthcare system properly. As a result, the government’s regulation is highly needed because it is only the authority that can assure the preservation of the equality and common accessibility principles of the health care service. Otherwise, every agent of the treatment process pursues the personal interest that, consequently, affects the cost formation. Hence, the key idea is that the present health care system lacks clarity and unity.

As a consequence, one should suggest that the government’s intervention is essentially required in order to improve the current set of things. It is assumed that the country might implement a universal mandate for the healthcare coverage to resolve the existing problems. Thus, the USA can make a shift to a multi-payer insurance system that has been successfully employed by other members of OECD, such as Germany and Japan for a long time, and, thus, has already proved its efficacy (The U.S. Health Care System: An International Perspective 2014). The country will manage to eliminate the administrative costs for billing on condition that the government supplies its citizens with universal insurance and sets the uniform rates for the healthcare workers.

Reference List

Morris, M, Devlin, N & Parkin, D 2007, Economic Analysis in Health Care, John Wiley & Sons, Chichester.

Mwachofi, A & Al-Assaf, AF 2011, ‘Health Care Market Deviations from the Ideal Market ‘,Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal, vol. 11, no.3, pp. 328-337. Web.

The U.S. Health Care System: An International Perspective 2014. Web.