The Canadian labor movement has been defensive, confronting significant difficulties in their authenticity, role, and viability within the working environment (Brookes, 2013). Unionism has been challenging globally and Canada’s labor union is not an exception (Brookes & McCallum, 2017). The history of labor movements has not been diplomatic in Canada.

The eighteenth to nineteen century was marked by repression, strikes, depression, and layoffs. Today, labor unions use structures laid out by their predecessors. Strikes, which signify the height of most labor demands, follow a sequence of denial, suffering, and collective bargaining. In some events, collective bargaining was accepted as a last resort to establish a truce between union members and the government (Fichter & McCallum, 2015). The Canadian labor movement is a huge monetary and social power (Fichter & McCallum, 2015). One of every four workers is a member of a registered trade union in Canada, with participation, equally divided between male and female employees.

The Canadian labor movement is judged to have been effective and successful in adapting to monetary and social changes, which have influenced union movements in industrialized nations. Canadian labor unions remain a critical force in the labor struggle and have been occupied with a continuous procedure of reestablishment and internal change to sustain its relevance. Toronto labor unions have a history of enhancing laborers’ regular daily existences. The benefits today are direct results of dedication and perseverance among union groups in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

This paper examines two labor movement plaques and their significance in the emancipation of labor employees in Canada. Civilization came with its price in most developed nations, with labor unions being a decisive catalyst for better welfare. The paper describes the site location, historical significance, and results of the labor movement in Toronto. Thus, the history of the labor movement in Canada can be described using the Labor Lyceum and the Printers Strike of 1872.

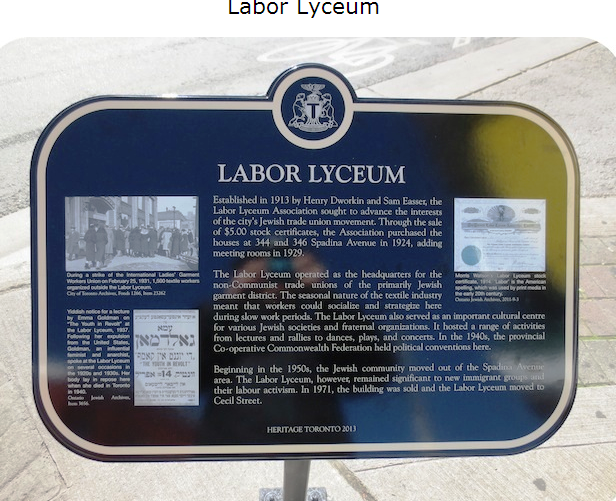

The Labor Lyceum Site

The Labor Lyceum site was the epicenter of political activism for Toronto’s labor workers. Members of the union formed a trade association with a common goal. They became known as textile union workers. Situated in the Southwest corner of Spadina Avenue, the Labor Lyceum was an imperative social center through which the character of Jewish workers was shaped. J.B. Salsberg was a notable activist who played his part in the emancipation of Jewish textile workers. The Activists argued that Jews in Spadina owned no establishment and must change the norm. As a result, the Jewish union members acquired a building and named it the Labor Lyceum. Aside from the union movement and demonstrations on the site, the building was a cultural center for Jewish celebrations, events, and a beer arena.

The Labor Lyceum site concentrated on Jewish roles in the garment industry. The Labor Lyceum plaque commemorated the struggles of Jewish settlers in 1931. Tourists are delighted in observing the destinations of previous Jewish neighborhoods and lifestyles in the Kensington region. The Jewish settlers of Toronto developed from 3,000 to 45,000, a rate of development that was four times the remaining city population. Because of this expansion, Toronto’s economy was developing. However, textile workers were challenged with critical conditions on the processing plant floors. The living conditions of textile workers were not encouraging, and they needed a change in attitude from their superiors. In 1913, forged by the hardship, the Jewish garment workers established an association led by Henry Dworkin and Sam Easser. Dworkin and Easser urged their members to buy shares for the Labor Lyceum union. Each member was mandated to pay five dollars for the shares. In 1924, the union bought two houses at 344 and 246 Spadina Road.

The seasonal pattern of the garment trade implied that laborers could mingle and plan at the Labor Lyceum during moderate work periods. Regardless of their initial endeavors, the conditions and welfare of textile workers were challenging. The production environment was not accommodating, the lighting was poor, and there were no heating lamps and ventilation. Besides, the alleged authorities were responsible for the workload, separating the conveyance of work. Equipped with stopwatches, they incited “speedups” when the workload expanded. The gross misconduct of the authorities was not investigated, making it simple for them to exploit laborers who feared for their occupations. With the pending implosion, union members converged on the Labor Lyceum site to chart a way forward. Their mission was to enforce an immediate resolution of all pending issues facing them. After due consultations, the union organized a congress at the Labor Lyceum site and agreed to press their demands with strike action.

On February 25, 1931, the garment workers put down their work, ceased their machines, and relinquished their posts, leaving the clothing shops to create an awareness of their plight (Klikauer, 2017). Their show prompted a general strike of dressmakers that required a fifteen percent increase in compensation, acknowledgment of the labor union, and the arrangement of a reasonable and unbiased judge to consult on future labor negotiations (Fichter & McCallum, 2015). Although they were unsuccessful, the strike exposed the conditions in the principally Jewish textile neighborhood. During the peak of labor activities in 1859, the Labor Lyceum was a central command for the transcendent Jewish union in the Spadina zone. After World War II, the Labor Lyceum site became a stopover point for Jewish evacuees from Europe. Refuges were given shelter, food, and clothing and at some point assigned to jobs in the garment industry. The Labor Lyceum site became a significant building for Jewish settlers and their labor activities.

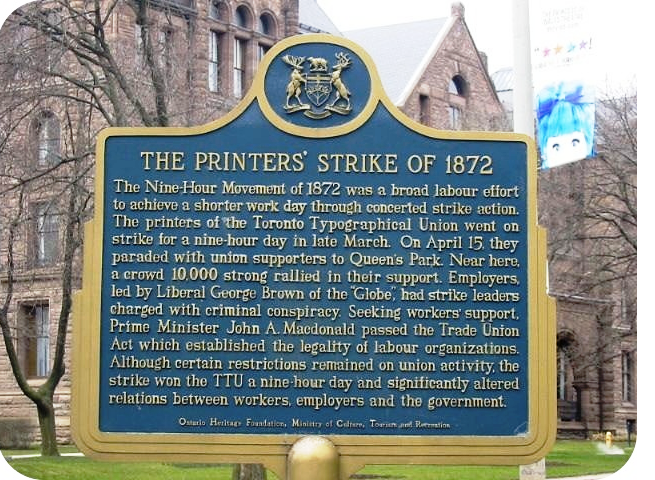

The Printers’ Strike of 1872

The historical plaque is located at the East corner of Queen’s Park Crescent

- Location: Toronto

- Province: City of Toronto

- District: City of Toronto

Another historical Toronto plaque is the Printers’ Strike of 1872. When union leaders organized a congress and went on strike for a nine-hour workday in 1872, a pack of 10,000 assembled at Queen’s Park to press their demands. The strike action was successful as the authority led by Sir John Macdonald was pressured to present the Trade Union Act. The Toronto Printer’s Strike is one of the historical sites that commemorated the activities of labor unions in Canada. The location was a rallying point for the notable nine-hour movement. The nine-hour revolution of 1870 was a global labor activity striving for favorable working conditions. In January 1872, railroad employees and other laborers established the nine-hour labor movement. The union members agreed that a reduction in work time would improve their extra circular activities, which include family time, and community service. After due consultation with its members, the laborers clarified that society, in general, would profit from shorter workdays because people would have more opportunities for family and other activities.

From Hamilton, the movement spread to different parts of Canada. The labor league became popular and was known as Canada’s first mass laborer’s union. Toronto is imperative to the nine-hour development since it was there that words were changed energetically. The Toronto union took up the requests that had begun in Hamilton and other regions. However, authorities questioned their legitimacy and called their threat a bluff. On 25 March 1872, the printers union went on strike. The procession included walking groups and signs broadcasting the requests of the printers. The gathering began the walk with 2000 people and when they had made it into Queen’s Park the group had developed to around 10,000. The strike prompted numerous positive results. Consequently, the labor unions were authorized and the general population demonstrated that they were keen on resolving employee’s welfare. After the strike of 1872, all labor unions demanded 54-hour weeks for their employees. The printers of Toronto were without a doubt pioneers in the battle for shorter workdays.

Conclusion

The Toronto labor sites remain the pivot of most labor struggles in Canada. The events shaped the labor union movement of the twenty-first century. This accounts for the commemoration of plaques that reveal the significant contribution of a previous union activist. The two historical sites discussed in this paper reflect a part of the labor history in Canada. Based on this analysis, it is evident that the historical labor sites are significant for the modern union movement. Although some of these Plaques are significant to foreigners, the overall interest represented worker’s welfare and working conditions. The account of the struggle of textile workers and printer’s welfare summarizes the contributions of labor unions in Canada.

References

Brookes, M. (2013). Varieties of power in transnational labor alliances: An analysis of workers’ structural, institutional, and coalitional power in the global economy. Labor Studies Journal, 38(3), 181–200.

Brookes, M., & McCallum, J. (2017). The new global labor studies: A critical review. Global Labor Journal, 8(3), 201-218.

Brown, A [image]. (2004). Toronto’s historical plaques. Web.

Brown, A [image]. (2013). Toronto’s historical plaques. Web.

Fichter, M., & McCallum, J. (2015). Implementing global framework agreements: The limits of social partnership. Global Networks, 15(1), 65–85.

Klikauer, T. (2017). Workers and trade unions in the USA. Journal of Labor and Society, 20(1), 129-135.