Introduction

Yosemite National Park is located in central California and occupies an approximate 1,931 square kilometres. According to Schoch (1996), the park has a wide variety of wildlife species, which makes it very attractive to tourists. Even without the wildlife, Yosemite is a place of legendary beauty, something that makes the park very appealing to nature tourists. Initially, Schoch (1996) notes that the Park Service engaged in relentless marketing campaigns in order to position the park as the preferred tourism site for most Americans. To enhance the image of the park further, the Park Service even eliminated animals that posed a danger to visitors (Schoch 1996). As a result of the marketing efforts and the activities that Park Service took to make Yosemite a safer place to tour, Schoch (1996) notes that tourists have over the years been flocking to the park. The high tourist numbers are advantageous for business owners in and around the park, but have also caused considerable damage to the park’s habitat.

This paper aims at providing a critical analysis of some of the intervention measures taken by the Park Service in Yosemite. The paper is inspired by the knowledge that the Park Service needs to balance visitor’s interest in the park with the need to preserve the pristine state of the park for future generations. The paper has a discussion section that includes an analysis of the environmental, economic, and socio-cultural effects of high tourist numbers in the park. The paper’s conclusion section restates the different effects that high visitor numbers have in the park.

The environmental impact of high visitors numbers in Yosemite

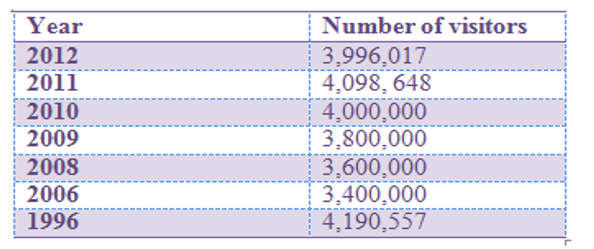

In 1997, Yosemite had an annual visitor rate of four million tourists (Goeller 1997). Recent statistics from the National Park Service (NPS) (2014) indicates that the number of visitors has not changed much since the mid-1990s. The table below is a reflection of the visitor numbers in different years.

To cater for all the park visitors, NPS and other private investors have set up 1,133 structures (NPS 2014). Additionally, the park has 1,504 camping sites; 1386 lodging units; 214 miles of paved roads; 20 miles of paths; 800 miles of trails; and 86 miles of graded routes (NPS 2014). Collectively, the aforementioned facilities and access roads have caused major harm to Yosemite’s natural habitat. The United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) (2009, para. 14), for example, notes that the increasing roads and trails in the park “have caused habitat loss in the park and are accompanied by various forms of pollution including air pollution from automobile emissions”. Air pollution was reportedly so bad in Yosemite, that UNEP (2009) notes that the aerial view of Yosemite was occasionally hindered by smog. The smog not only hindered the park’s visibility from above, but was also detrimental to the well-being of both plants and animals in the park (UNEP 2009).

Arguably, the Park Service has not been ignorant of the damage done to the environment in Yosemite. The Associated Press (2014), for example, notes that the Park Service has expressed its intention to cap visitors to Yosemite at four million people annually. The decision to cap the visitor numbers was ostensibly reached when it become apparent that the river running through the park needed protection from destructive human activities. The Park Service also announced its intention to introduce shuttle buses in order to ease the flow of traffic in the park (Associated Press 2014). While the foregoing initiatives are arguably an indicator that the Park Service is aware of the environmental challenges facing the park, a critical analysis would reveal that they are anything but sufficient. For example, capping tourist numbers at four million people is arguably nothing new. After all, Figure 1 above shows that the average annual tourist numbers are about four million. A critic who is arguably right was quoted by the Associated Press (2014, para. 14) saying that the Park Service “Has chosen to nibble around the edges instead of taking a big bite out of the congestion and crowding that degrades Yosemite Valley”. True to the foregoing argument, the tourist cap and the decision to introduce shuttle buses in the park cannot remedy the destruction brought about by too much human and automobile traffic. Finding a long-lasting solution to Yosemite’s environment degradation will take more decisive and strategic decisions than what Park Services have so far done.

The economic impact of high tourist volumes in Yosemite

According to NPS (2013, para.1), “Yosemite national park tourism creates over $379 million in local benefit”. Further, NPS (2013) indicates that tourists spend at least $13 billion on businesses located within a 60 miles radius of the park. The Park Service further adds that visitor spending in and around the park has an estimated $30 billion in the larger American economy (NPS 2013). The foregoing assertion by NPS is based on a 2011 report that further indicates that more than five thousand jobs were supported by tourism-related activities in the area surrounding the park (NPS 2013).

While admitting that national parks have significant implications for the economic well-being of a region, Power (1998, p. 33), however, indicates that “the primary objective for establishing national parks was not usually the stimulation of local economic activity in particular communities.” Power (1998) argues that national parks are generally established for purposes of giving citizens a pristine location where they can enjoy nature. The author further argues that national parks are created to guard the inherent values that people associate with the sites (Power 1998). As pristine enjoyment locations and as places where the intrinsic value of sites are protected, national parks “could be given expression, at least partially, as economic values” (Power 1998, p.34). In other words, there are other economic values (distinct from the monetary gains from tourism revenues) that are attached to national parks. A major concern arises when environment degradation becomes rife in such parks as Yosemite. Normally, environment degradation leads to the loss of economic values that cannot be quantified in monetary terms (Power 1998). For example, future generations may not experience the same quality of pristine beauty that is currently in the park. Additionally, future generations may not understand the inherent values that were previously attached to the game parks.

Another arguably valid argument by Power (1998) indicates that the land that is fit for the establishment of national parks is very scarce; consequently, the decision to establish a national park in a particular location is usually an economic decision. Power (1998) supports the foregoing argument by noting that land that is fit for the establishment of national parks can be used for several other purposes. However, the establishment of national parks in a particular place means that those who chose to establish it must have forgone the pursuit of other human activities in the same piece of land and instead, chose to preserve the pristine nature of the land. With high tourist numbers, however, hundreds of years’ worth of conservation efforts can be undermined. Putting conservation at risk puts into question the initial economic choices made by the people who chose to establish a national park. Yosemite is not safe from such practices.

Power (1998) further questions the accuracy of the economic theory that hypothesizes that local economies where national parks are located thrive on the overexploitation of the natural resources in the same parks. In Yosemite for example, the 1997 floods led to the close of the park, and as a result, different analyses (NPS 2013; Padraig 2012) have argued that Mariposa County, which neighbours the park, lost an estimated $1.67 million. While the monetary loss estimates may have been right, Power (1998) notes that money generated through tourism is not the only economic implication that national parks have. He argues that even without the overexploitation of national parks, the economy of the host community would not suffer. He argues that good environmental quality in the park would make the host community a better place to work and live, which in turn would spur economic activity. The enhanced economic activities would lead to diversification in spending and investments, which would in turn make the community more developed and self-sustaining. Pegging almost an entire economy of the host community on the national park alone can only lead to more degradation since more tourist numbers will bring more revenues. In the long-term, however, Yosemite will lose its attractiveness to tourists hence compromising the entire economy and the dependent host community.

The socio-cultural impact of high tourism numbers in Yosemite

Among the most prominent socio-cultural impacts of high tourism numbers in Yosemite is the social dislocation of the native tribe that lived in the Yosemite Valley (Ritchie & Crouch 2003). As has been noted by the Barcelona Field Studies Centre (2013, para. 12), “The Ahwahneechee Indigenous Indians have not received any compensation in the form of money nor land for their loss of the Yosemite area in 1851”. In other words, no regard was paid to the social and cultural implications that the establishment of the national park had in the Indigenous communities. Porter (2012) specifically notes that Indians who were the native residents of Yosemite Valley were driven out of the area with brutal military force. Over the years, the Park Service has shown little or no regard to the ethnographic interpretation that aboriginal people have towards Yosemite (Mason 2014; Porter 2012). According to Ross (2013) the displacement of native Indians from Yosemite has to a great part, placed them at an increased social risk, since the valley was a source of their physical, social and spiritual wellbeing.

In addition to issues relating to the welfare of native Indians who occupied the Yosemite Valley, the Barcelona Field Studies Centre (2007) notes that the increased tourism numbers have led to court battles between environmentalists and those advocating for free access to the park. One such case is the Friends of Yosemite Valley v. Kempthorne. In the case, the Court of Appeals ruled that the Park Service had failed in its mandate to limit tourists’ use of particular scenes in the park (Access Fund 2008).

Another social impact of increased tourist numbers at Yosemite involves the possibility of infections being passed from human to wild animals and vice versa. In 2012, for example, there was a Hantavirus outbreak in the park (Walters 2014; Wilson 2012). At least ten people were infected with the virus, and of these, three succumbed to the infection (Barcott 2012). Although the infection rate was contained, Quammen (2013) argues that the possibility of the next human pandemic having its genesis from the interactions that humans have with wild animals cannot be downplayed.

Conclusion

This paper has provided an analysis of the economic, socio-political and environmental impacts, which high tourist numbers have in Yosemite National Park. The paper notes that the environmental impacts are generally negative, to the extent that the Park Service has capped the annual number of tourists to Yosemite. The tourist cap is arguably an inadequate measure of managing the adverse effects of too much human and motor vehicle traffic in the park. The paper has also identified that in addition to the obvious economic impact that high tourist numbers have on the local economy in areas bordering Yosemite National Park, there are the not-too-obvious economic implications which cannot be ignored. The paper has argued that Yosemite was established to protect a pristine location that represents inherent values that cannot arguably be found in other locations. Overexploitation by too many tourists is, therefore, likely to devalue the location and its economic value. The effects of such devaluation will not only be felt by communities surrounding the park, but by future generations too. Finally, the paper has looked at the socio-cultural effects of the park, and noted that such effects are varied. Among the most prominent effects relate to the dislocation of native Indians who occupied the Yosemite Valley, and the Hantavirus outbreak that occurred in 2012 in the park. The latter is significant because it shows how interactions between humans and animals can spread some animal diseases to humans and vice versa.

References

Access Fund 2008, Two access lawsuits decided: Yosemite National Park. Web.

Associated Press 2014, ‘New Yosemite preservation plan includes limit on visitors’, CBS San Francisco. Web.

Barcelona Field Studies Centre 2007, Yosemite court battle ponders access vs. Protection. Web.

Barcelona Field Studies Centre 2013, Yosemite: management problems and issues. Web.

Barcott, B 2012, ‘Death at Yosemite: the story behind last summer’s Hantavirus outbreak’, Outside Magazine. Web.

Friends of Yosemite Valley v. Kempthorne, 520 F. 3d 1024 – Court of Appeals, 9th Circuit 2008. Web.

Goeller, S 1997, ‘Yosemite National Park and eco-tourism’, TED Case Studies. Web.

Mason, C 2014, Spirit of the rockies: reasserting an indigenous presence in Banff National Park, University of Toronto Press, Toronto.

National Park Service (NPS) 2014, Yosemite National Park California: Park statistics. Web.

NPS 2013, Yosemite National Park tourism creates over $379 million in local benefit. Web.

Padraig, J 2012, ‘Mariposa County – overview’, County Report, pp. 1-135.

Porter, J 2012, Land and spirit in native America, ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara, CA.

Power, T 1998, ‘The economic role of America’s national parks: moving beyond a tourist perspective’, The George Wright Forum, vol. 15, no.1, pp. 32-40.

Quammen, D 2013, Spillover: animal infections and the next human pandemic, Random House, New York.

Ritchie, J & Crouch, G 2003, The competitive destination: a sustainable tourism perspective, CABI, Wallingford, Oxford.

Ross, J 2013, American Indians at risk- volume 1, ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara, CA.

Schoch, R 1996, Case studies in environmental science, Jones & Bartlett Learning, Burlington, MA.

United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) 2009, Tourism’s three main impact areas, Web.

Walters, M 2014, Seven modern plagues and how we are causing them, Island Press, Washington, DC.

Wilson, S 2012, Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome outbreak in Yosemite Park, California, USA, Web.