Introduction

The process of globalization has brought about the necessity to become more competitive and become more cost-effective producers in order to counter the intensive competition in the market. This has led to the adoption of outsourcing models. The intensified competitive business environment has led many firms to send their non-core operations to a vendor (supplier or manufacturer) and concentrate only on core operations. The intention of these firms is to reduce the cost of production by specializing and making the firms’ labor and resources more efficiently. Such a trend has crept into the practices of both labor and technology-intensive industries.

Industries like the automobile, information technology, electronics (especially white goods), retail, and clothing and footwear industry have been engaged in international outsourcing. Trade-in parts and components, in middle products or in fragments of final goods (many names have been coined in this respect) has exhibited a dynamism exceeding that of trade in final goods. The main argument was that only a large scale of operation and an international outlook could give a company the necessary knowledge to see outsourcing opportunities and sufficient resources to take advantage of them. There exists evidence in support of a rapid growth of intra-firm trade carried out by large multinationals (Helleiner, 1981).

This has been particularly prominent in the clothing and footwear industry where the well-known retailers like GAP, H&M, Benetton, Levi, Nike, Adidas, et al. follow an outsourcing model where they have outsourced their core-operations to vendors in less developed countries (LDCs) and they concentrate on branding and marketing the products (Baudisch, 2006a; Baudisch, 2006b; Frenkel, 2001; Hadjimichael, 1990; Donaghu & Barff, 1990). However, as globalization has leveled the field of competition, and liberalization has torn down barriers to entry, the alleged advantage of large international firms has somewhat diminished.

Research Implication

This trend in the US footwear industry has experienced an increase in fragmentation in production and outsourcing. The main driver of this process was the US economy adjusting to structural changes and attempting to remain competitive vis-à-vis Western Europe and Japan. Geography, costs and history all combined to select efficient sub-suppliers of US firms in Canada and Latin America. This study concentrates on determining the US footwear industry and the emerging trend in the industry to outsource its operations. The study will provide insight into the emerging trend of fragmented international procurement of footwear by US manufacturers and its effect on labor employment and wages, turnover and profitability of the industry as well as domestic consumption of the imported footwear, and its effect on trends of ethical manufacturing.

The study will provide a comprehensive understanding of the US footwear industry and the emergence of fragmented outsourcing in the industry. It will provide an understanding of whether outsourcing can provide a competitive advantage for the US footwear manufacturers in the international market or they have become a strategic necessity. Further, we will also evaluate the ethical issues concerned with the process of outsourcing, especially in less developed countries (LDCs).

The study has implications for the growing trend of globalization of industries, domestic markets, and management strategy. With increasing globalization, industries as a whole have to adopt new strategies to combat the emerging market demands. This necessity gives birth to new ideas to be competitive in the market. Further, the study also provides, with the example of the US footwear industry, the necessity of lean manufacturing and a streamlined supply chain to minimize the cost of production in order to gain a competitive advantage in a market that faces excessive competition due to globalization. It also shows how companies like Nike, Adidas, etc. have taken advantage of the globalization, of not only the product market but also of the production market, and has become world leaders in their genre.

Research question

Outsourcing is beneficial and increases the profitability of the organization (Jones, Kierzkowski, & Lurong, 2004). This research aims to understand this phenomenon from different aspects: financial, operational, strategic, and stakeholders (ethical point-of-view). The primary question that the study tries to answer is how beneficial the trend of outsourcing production to international vendors to gain cost-advantage is to the domestic industry both in pecuniary and non-pecuniary terms.

Methodology

The subject of the study is the understanding of the emerging trends of outsourcing that have developed in the retail industry. We specifically consider the case of the US footwear industry. In order to ascertain the evolution and benefits of outsourcing, we consider the financial benefits that the industry has achieved by outsourcing its productions to international vendors. To do a trend analysis of the footwear industry pre-and post- outsourcing we will work on historic data of production, revenue, and profit. For non-pecuniary effects, we will analyze the effect of outsourcing on domestic labor employment in the industry and the changing trends along with the emerging ethical issues.

The research is divided into five sections. The first, as we have already seen is the introduction to the topic. The second deals with a detailed review of the literature on fragmented outsourcing and its theoretical background and what empirical research on the subject has to suggest. The third deals with the methodology section where we describe the different tools adopted for the research and case study development and analysis. The fourth section deals with the data analysis of the overall industry and substantiates the industry trend with the micro organization trend taking the case of Nike. Here we do an analysis of the financial and performance-related issues, outsourcing, and cost of production-related issues, supply chain, and ethical concerns. In the fifth section, we draw a conclusion to our discussion.

Literature Review

In the literature review, we do a theoretical as well as an empirical view of the available literature to understand what theory and empirical evidence say about fragmented production and outsourcing.

Emergence of Growth of Fragmentation Outsourcing

International fragmentation of production and the resulting trade in parts and components were already present in the early 1960s. The main driver of this process was the US economy adjusting to structural changes and attempting to remain competitive vis-à-vis Western Europe and Japan. Geography, costs and history all combined to select efficient sub-suppliers of US firms in Canada and Latin America. In analyzing the new phenomenon, the initial attention of trade theorists was concentrated on individual cases of outsourcing.

In an early World Bank study, David Morawetz (1981) provided an answer to the question Why is the Emperor’s New Clothes not made in Colombia? In responding to this query, he also identified the factors behind Colombia’s initial success: Abundance of cheap labor with sufficient skills, relatively low costs of transportation, communications access and location in similar time zones all helped to launch and coordinate a new form of international production sharing. Unfortunately, macroeconomic instability, political tensions, trade union upheavals and exchange depreciation and uncertainty led American producers to switch to sub-suppliers located in East Asia. After being a regional phenomenon, outsourcing went global. Notwithstanding, other Central and Latin American countries moved in to seize the new opportunity.

The advantages of international fragmentation in the textile, clothing and footwear industries spread to other production sectors. And what was good for the United States could also be advantageous for other countries. Outsourcing soon characterized trade around the globe. It spread to countries in Eastern Europe even before they abandoned planning and switched to becoming market economies. IKEA established production facilities in Poland in the 1970s.

It is generally thought that international corporations were most responsible for these initial moves towards international outsourcing. The main argument was that only a large scale of operation and an international outlook could give a company the necessary knowledge to see outsourcing opportunities and sufficient resources to take advantage of them. Helleiner (1981) provided some evidence in support of a rapid growth of intra-firm trade carried out by large multinationals. Even today, the role of large international firms is often emphasized or even overstated. However, as globalization has leveled the field of competition, and liberalization has torn down barriers to entry, the alleged advantage of large international firms has somewhat diminished.

Countries in East Asia have been important in the international fragmentation of production and outsourcing. We have already alluded to the fact that in spite of geographic proximity, U.S. producers found Latin America somewhat lacking in economic and political stability and they soon voted with their feet by moving to East Asian locales. One striking feature of Asian trade in parts and components has been its selective character. Exports of components of office and adding machinery and of telecommunications equipment represented in the late 1990s just over half of the total regional exports of parts and components. Regional production sharing networks interact and support one another, leading to an expansion in trade in parts and components within East Asia as well. Ng and Yeats (2003) have established that: Asian global exports of components increased more than fivefold over the 1984-96 periods, while total exports of all goods rose by a factor of approximately 3. However, the value of component exports to the region grew by a factor of about 10, which was roughly double that for all regional trade. These trends in intra- and extra-regional East Asian trade in parts and components suggest major forces operating in that part of the world economy.

Shifting output fragments to Asia in order to increase the competitiveness of American products in international markets has been practiced by large, medium-sized and small firms as a part of their restructuring activities.

Research has shown that a trade of fragmented manufacturing of components has increased the growth of the industry (Jones, Kierzkowski, & Lurong, 2004). This has been specifically seen in the case of East European countries for the case of automobiles and furniture. A new dimension to regional production sharing in Europe has been added by the economic transformation of Eastern Europe. Integration with the world economy and especially with the European Union has been a key driver of reforms undertaken by transition economies. This has meant more than just a lowering of trade barriers.

Also involved are geographic realignments of trade patterns and the development of new products for exports to much more demanding markets. In a relatively short period of time transition economies have intensified intra-industry trade with Western Europe. They have also developed production-sharing arrangements with numerous European Union firms. According to Kaminski and Ng (2001), all ten new members of the EU engage in trade in parts and components. Particular progress has been achieved in furniture and automobiles. Egger and Egger (2001) show that the flexibility in trade barriers and low wages in Eastern Europe has persuaded countries such as Austria to reallocate labor-intensive stages of production to that region.

Theory of Fragmentation Outsourcing

In order to understand the outsourcing and the principal features underlying the rise in international outsourcing of production and services of Nike it is essential to understand the underlying theoretical background of the strategy. As sketched out by Jones and Kierzkowski (1990; 2004; 2005), the existence of increasing returns is crucial in the understanding of the outsourcing phenomenon. Adam Smith emphasized division of labor, whereby as scale increases each worker can become more specialized in particular tasks. The extent of the market, i.e. scale of production, would determine the lengths to which such division of labor can proceed. This idea is generalized by considering that at low levels of output resources are combined in an integrated production block. Such a process can be vertically fragmented into two or more production blocks that could each be produced in a separate locale. The attraction for such a fragmentation could be found in different requirements for labor skills, with one region (or country) containing labor of skills more appropriate to one fragment and another region populated by labor relatively more productive in the other fragment.

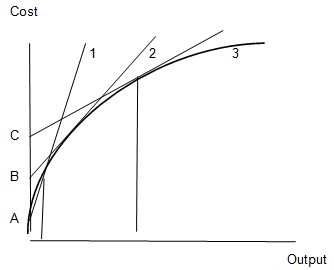

The fragmentation theory as illustrated below is an extension of Adam Smith’s idea of division of labor (2005). The basic ideas of the fragmentation scenario as well as the consequent feature that increasing returns to scale systematically emerge as production increases are illustrated in Figure 1 (Jones, Kierzkowski, & Chen). The figure shows how total costs of production are positively related to scales of output. For example, ray 1 from the origin illustrates productive activity that takes place in a single location under constant returns to scale technology. By contrast, line 2, flatter than ray 1, shows how total costs might vary with the output if the originally vertically integrated production process were split up into a pair of production blocks. This could serve to reduce marginal costs of production.

The reason might be that workers in one area of the country tend to have different skills from those in another area, and the skills required in each production block differ so that a dispersion of activity according to comparative advantage could lower marginal production costs. This is a Ricardian type of story. Alternatively, it might be the case that the production blocks differ from each other in the proportions of different factors that are required. Labor-intensive production blocks would better be located in regions in which labor is relatively inexpensive compared with productivity. This would be a Heckscher-Ohlin type of difference. Such fragmentation, however, introduces new costs – the costs of connecting the two production blocks by service links such as transportation, communication, and general costs of coordinating activities into a smooth sequence resulting in the production of the final product. This would represent outsourcing within the country, and it could link production blocks within a single firm or, alternatively, involve one firm making arrangements at arm’s length with a different firm in a different location.

Lines 3 and 4 in Figure 1 represent either splitting up the production process into more separate production blocks, allowing a finer degree of specialization according to comparative advantage and/or of engaging in international outsourcing, with some production blocks, say, being located in a different country (such as GAP does in India) in which the discrepancy between countries with different relative factor prices (compared with productivity) is even more pronounced than within countries. Again, such outsourcing may be kept within the (multinational) firm, or be let out to other firms via separate contracting (e.g. Nike in having production of athletic footwear located in East Asia). The terms outsourcing and fragmentation refer to moving parts to different locations, not necessarily to different firms.

Such a relationship is one of the connections to be tested in the next section. In addition, as previously noted, recent technological improvements in manufacturing link activities, as well as reductions in service regulations and a lowering of international barriers to services trade have all conspired to reduce the costs of manufacturing. As a consequence, in Figure 1, these changes would result in a lowering of the vertical intercepts of lines 2, 3, and 4, suggesting that even for a given level of output an increase in the degree of fragmentation and outsourcing may well be observed. These are the primary relationships for which we seek evidence. To the extent that such outsourcing activity is promoted, the new economic geography argument that increasing returns helps to promote increasing agglomeration of economic activity is contradicted, at least at the international level, by the evidence (Jones & Kierzkowski, 1990).

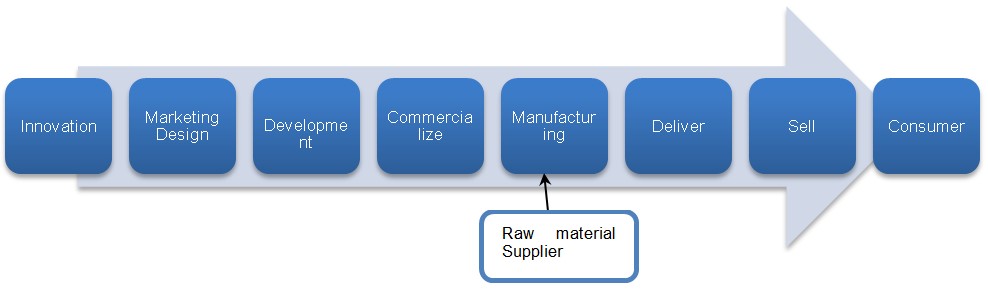

Traditional Footwear Supply Chain

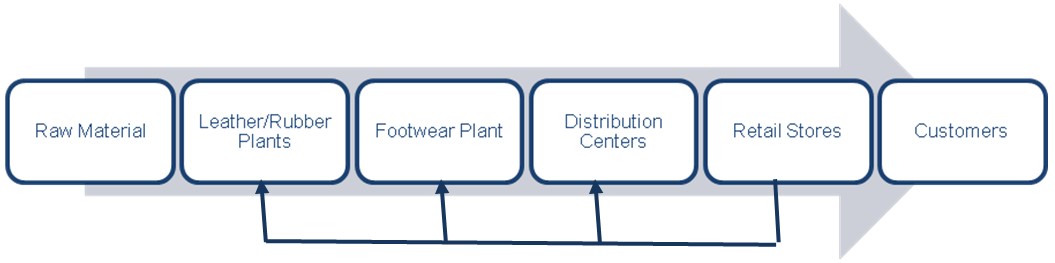

The sports footwear sector can be seen as a supply chain consisting of a number of discrete activities. Increasingly the supply chain from sourcing of raw materials via design and production to distribution and marketing is being organized as an integrated production network where the product is sliced into specialized activities and each activity is located where it can contribute the most to the value of the end product. When the location decision of each activity is being made, costs, quality, reliability of delivery, access to quality inputs and transport and transaction costs are important variables.

The supply chain in the sports footwear sector is illustrated in Figure 2. The dotted lines represent the flow of information, while the solid lines represent the flow of goods. The direction of the arrows indicates a demand-pull-driven system. The information flow starts with the customer and forms the basis of what is being produced and when. It is also worth noticing that information flows directly from the retailers to the raw material (rubber and/or leather) plants in many cases. The leather and textile sector produces for the footwear sector and for household use. In the former case, there is direct communication between retailers and raw material mills when decisions are made on patterns, colors and material. In the second case, raw material mills often deliver household appliances directly to the retailers.

At each link in the production chain to the left of the distribution center in Figure 2, there are usually several companies. In order to make goods, information, and payments flow smoothly, a number of logistics and business services are needed. Depending on the size and development of the host economy, such services are provided by the lead firm in the supply chain or independent service providers in the more advanced countries.

An illustration of how a supply chain operates is as follows: lean retailers in the United States typically replenish their stores on a weekly basis. Point of sales data is extracted and analyzed over the weekend and replenishment orders are placed with the manufacturer on Monday morning. The manufacturer is typically required to fill the order within a week, which implies that the manufacturer will always have to carry larger inventories of finished goods than the retailer. How much larger depends on his own lead time and demand volatility. The larger the fluctuations in demand, and the larger the number of varieties (e.g. style, size, color) the larger the inventory has to be. On the other hand, the shorter the manufacturer’s lead time, the better the demand forecasts and the larger the market, the less the inventory needed relative to sales.

The size of the market matters, since the variation of aggregate demand from a large number of consumers is less than the variation over time of a few consumers. Upon receiving the replenishment order, the manufacturer will fill it from its inventory and then on the basis of the gap between the remaining inventory and the desired inventory level, will make a production order to the production plant, of which the manufacturer may have several in different locations. The retailers may order large quantities of, say, tennis shoes spread over a number of producers in several low-wage countries. In order to ensure that the tennis shoes are similar and can sell under the same label, the buyer often buys leather and accessories in bulk and provides its clothing suppliers with these inputs. In addition, buyers often also specify the design and assist the producers in providing the desired quality (Donaghu & Barff, 1990; Frenkel, 2001).

The underlying technological developments of modern supply chain management are discussed below. Given the demand-pull nature of the supply chain, it is natural to start the discussion with the retail sector, followed by the footwear industry.

Supply chain and Cost Reduction

It has long been recognized by some that the key to major cost reduction lies not so much in the internal activities of the firm but in the wider supply chain. According to Borsodi (1929) expressed it in the following words:-

In 50 years between 1870 and 1920 the cost of distributing necessities and luxuries has nearly trebled, while production costs have gone down by one-fifth …. What we are saving in production we are losing in distribution. (Borsodi, 1929, p. 3)

The situation that Borsodi describes can still be witnessed in many industries today. For example, companies who thought they could achieve a leaner operation by moving to just-in-time (JIT) practices often only shifted costs elsewhere in the supply chain by forcing suppliers or customers to carry that inventory. The automobile industry has shown some of the lean thinking and just in time practices and has exhibited those characteristics (Womack & Jones, 1990). A recent analysis of the Western European automobile industry (Holweg, 2002) showed that whilst the car assembly operations were indeed lean with minimal inventory, the same was not true upstream and downstream of those operations.

For many companies, their definition of cost is limited only to those costs that are contained within the four walls of their business entity. However, it has been argued that today’s competition takes place not between companies but between supply chains, hence the proper view of costs has to be ‘end-to-end’ since all costs will ultimately be reflected in the price of the finished product in the final marketplace.

The need to take a supply chain view of cost is further underscored by the major trend that is observable across industries worldwide towards out-sourcing. For many companies today, most of their costs lie outside their legal boundaries. Activities that used to be performed in-house are now out-sourced to specialist service providers. The amazing growth of contract manufacturing in electronics bears witness to this trend. If the majority of an organization’s costs lie outside the business then it follows that the biggest opportunities for improvement in their cost position will also be found in that wider supply chain.

As outsourcing increases, the supply chain becomes more like a network than a chain (10) and, as a result, the number of interfaces between organizations increases. It is our contention that a growing proportion of total costs in the network occur at these interfaces. These costs have sometimes been labeled ‘transaction’ costs but in truth, they are much more than the everyday costs of doing business. These costs result as much as anything does from the lack of transparency and visibility across organizational boundaries. When we talk of visibility and transparency, we mean the ability to see clearly from one end of the supply chain to another and, in particular, to share information on supply and demand issues across corporate boundaries.

US Footwear Industry

The US footwear underwent various changes since the 1950s when there was a complete monopoly in the market by USMC (Baudisch, The Emergence of the Global Value Chain for the U.S. Footwear Industry, 2006b). In the 1960s there emerged an era of shoe imports in the US market.

Prior research on the footwear industry in the US has provided qualitative and quantitative overviews about the retailing industry in the 1990s (Gereffi, 1999; Korzeniewicz M., 1994; Schmitz & Knorringa, 2000). The 1990s saw a surge of specialty and discount formats in the US market. Furthermore, the retail stores went either upscale or low-price, leaving the middle segment in terms of quality and price.

On the international front, retailers and manufacturers, alike were acquiring large importers to shore up their position in global sourcing networks, For example, Payless ShoeSource International, the largest U.S. footwear importer, is owned by May Department Stores; and Meldiso, a division of Melville Corporation, handles international purchasing of shoes for Kmart. Pagoda Trading C., the second-biggest U.S. shoe importer in 1990, was acquired by the Brown Shoe Company, the largest U.S. footwear manufacturer. Unique organizational forms such as member-owned buyers or long-term contracts with other foreign traders are being used in overseas procurements since the 1990s (Cheng, 2001).

The US footwear industry underwent a technological change in the 1960s and the organizational change in the US market led to rising competitive pressure of imports (Baudisch, 2006b). Prior studies on the US footwear market, especially athletic shoes have emphasized the increasingly competitive pressure of imported shoes since the 1960s (Frenkel, 2001; Hadjimichael, 1990; Donaghu & Barff, 1990).

The income elasticity for footwear expenditure changed in the 1970s (Baudisch, 2006a). Before 1970 the growth of the U.S. footwear market had been smaller than that of personal income, since 1970 it has been larger, as the increasing share of personal income spent on footwear indicates (Baudisch, 2006b).

Kim (2003) analyzes aggregate U.S. demand of clothes and shoes between 1929 and 1994 and finds a structural change in consumer behavior for clothes and shoes in 1970. Since the 1970s consumers have been buying increasing quantities of shoes overcompensating the decline of prices that results from imports; this made the U.S. footwear market an “luxury” category as it has growing faster than overall income. Nevertheless, the U.S. footwear industry declined in this growing market.

Since the mid-1970s, the growth of the U.S. footwear market, which characterizes shoes a as luxury product category, is driven by continuous innovation accompanied by a falling relative price level (Baudisch, 2006a). As the market has been driven by simultaneous innovation and price competition, but U.S. production declines in this growing market, we presume that the U.S. footwear production was not able to produce at low prices and to be innovative at the same time. So, paradoxically, in order to survive competitive price pressure from imports, U.S. footwear producers had to change to less cost-efficient, but more flexible and innovation-friendly production organizations and compensation systems (Freeman & Kleiner, 1998).

To reduce the cost of production most of the US footwear producers were compensating workers at the innovation-unfriendly piece-rate system (Baudisch, 2006b). The strategy to lower production costs by using piece-rate compensation systems reduced the ability of U.S. producers to innovate. In addition, it is clear that the production of labor-intensive goods based in the USA could not compete with production in low wage countries. Chinese footwear production, accounting for over 85 percent of the U.S. consumption in 2001, has been organized with innovation-friendly time-rate compensation ever since because in this way plant owners can easily employ unskilled labor (Frenkel, 2001).

Given that foreign production can often provide similar quantity, quality, and service as domestic producers, but at lower prices, footwear manufacturers in developed countries have been caught in a squeeze. In the United States and Europe, many smaller and mid-sized shoe firms, feel they cannot compete with the low cost of foreign-made goods and thus they are defecting to the ranks of importers. The decision of many larger manufacturers in developed countries, however, is no longer whether to engage in foreign production, but how to organize and manage it. These firms supply intermediate inputs (cut leather, soles, thread, buttons, etc.) to extensive networks of offshore suppliers, typically located in neighboring countries with reciprocal trade agreements that allow goods assembled offshore to be re-imported with a tariff charged only on the value-added by foreign labor. This kind of international subcontracting system exists in every region of the world (Cheng, 2001).

A significant countertrend is emerging among established footwear manufacturers, however, who are de-emphasizing their production activities in favor of building up the marketing side of their operations by capitalizing on both brand names and retail outlets (Donaghu & Barff, 1990; Frenkel, 2001). The strengthening of brand names has led to a new focus on ‘concept stores’ that typically feature all the products offered by manufacturers and marketers, such as Nike, Adidas, Puma, Timberland, Geox, but also Levi Strauss, Disney, and Warner Bros (Baudisch, 2006b). These stores provide a direct link between manufacturers and consumers, bypassing the traditional role of retailers. Thus, a de-verticalization of production co-exists with a re-verticalization of brands and stores.

To sum up, since the 1970s, the competitive pressure in the U.S. footwear market has to lead to important transformations in terms of production processes alongside continuous product innovation (Donaghu & Barff, 1990; Hadjimichael, 1990; Frenkel, 2001). Moreover, this innovative pressure affected the industrial organization of the footwear sector throughout the entire sectoral chain of production. Several authors have analyzed the complex and globalized value chains of the footwear industry (Donaghu & Barff, 1990; Korzeniewicz M., 1994; Frenkel, 2001)

Currently the footwear industry faces intense competition from both international as well as domestic companies. The leaders in the footwear industry are Nike, Adidas, Fila, Converse, and New Balance, with nearly $7 billion in revenues domestically. Nike is the industry leader, with a 47% market share, followed by Reebok, a distant second at 16%, and Adidas at 6%. This category is facing decreasing demand and the rising popularity of alternative footwear, resulting in more pressure than ever before to achieve high gross margins through effective global sourcing practices.

Methodology and Data Collection

The methodology employed in addressing the subject of the increasing trend of fragmented outsourcing in the US market and the economic and strategic importance in doing so. We undertake a study of the US footwear industry and analyze the current trend of procurement in the industry. We will analyze the industry from 2001 to 2006. The data has been retrieved from the website of the American Apparel and Footwear Association (AAFA, 2008). The methodology used in this study is a correlation study of the industry trend with that of the production trend of an organization in the US. Here we consider the case of Nike. We chose Nike because it is the industry leader in turnover in the US footwear industry. Further, the company’s founders conceived the company on a model of outsourcing and international fragmented production (Nike, 2008a; HBR Case, 2005; Locke, 2002).

In order to analyze the effect of fragment outsourcing on the US footwear industry, we will undertake a quantitative analysis of the revenue and profitability of the industry vis-à-vis the increasing trend of import of footwear for domestic purposes. Research has shown that fragmented international manufacturing has led to the productivity of the industry (Kaminski & Ng, 2001; Ng & Yeats, 2003). We will try to test this assertion on the basis of the US footwear industry. Here we take the productivity of the industry in-terms of the turnover and profit of the industry annually. This will provide the impact outsourcing and procurement trend had on the industry’s turnover and profit. For this, we do a correlation analysis of the import of footwear to the change in profitability and the import consumption pattern of the domestic market.

Operational excellence leads to higher profitability and better industry performance (Camuffo, Furlan, Romano, & Vinelli, 2005; Gereffi, 1999). This has been shown in previous research for the apparel and automotive industry where a similar fragmented international outsourcing model had been adopted (Helleiner, 1981; Jones, Kierzkowski, & Lurong, 2004; Camuffo, Furlan, Romano, & Vinelli, 2005). In this study, we will analyze the international outsourcing trend of three US footwear (athletic) manufacturers and see how their strategy differs and so does their profitability historically from the year 1999 to 2006. Added to that, we will do a comparison of the shift of production base of Nike. This is done to show that the US-based companies were shifting their production bases abroad.

Previous research has shown that with the increasing international alignment of the supply chain and increase in manufacturing outsourcing, domestic employment, and wages decline (Abernathy, Dunlop, Hammond, & Weil, 1999; Donaghu & Barff, 1990; Baudisch, 2006b; Baudisch, 2006a). Given this proposition, we will try to understand the impact of outsourcing of the manufacturing parts of the business to international vendors on the employment situation in the home country i.e. the US in accordance with other research in the footwear industry. To do this analysis we will study the historical labor employment data and the relative wage data and try to see in which direction was their movement once the trend of outsourcing was adopted in the industry.

In order to understand the strategic development of the supply chain of the US footwear industry, we will try to trace the supply chain of the industry in the 1950s and then trace the changed supply chain once verticalization took place in the industry. Then we will compare the current supply chain of the US footwear industry with that of Nike in order to understand the difference between the two.

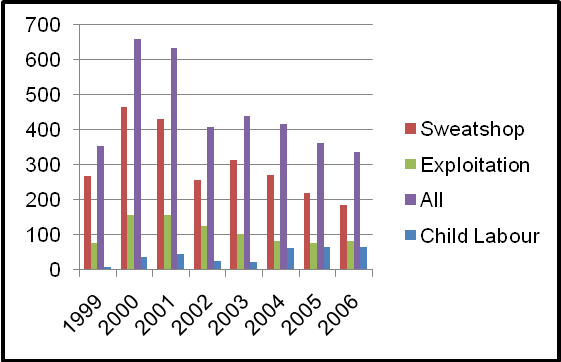

Further, there are different ethical issues that have emerged with ethical and responsible conduct of the US footwear manufacturers and the concept of ‘sweatshops’ at the contract factories. Questions regarding wages far less than the minimum wage, adverse working conditions, and child labors have been raised and has pin-pointed at the unethical code of conduct of the footwear companies (Donaghu & Barff, 1990; Hadjimichael, 1990; Jones, Kierzkowski, & Lurong, 2004; HBR Case, 2005). These issues are analyzed in this section. Here we will first do an analysis of the number of mentions of the words “sweetshop”, “exploitation”, and “child labor” in the text of the articles published in newspapers and periodicals for the last 10 years. We will do a similar analysis for Nike and correlate it with the data of the footwear industry in the US and try and understand the trend of ethical or unethical conduct of the industry or is it specific to the organization. Then we do a complete analysis of the study and try to answer our research question with the aid of the study that we have done.

The data for the research has been collected from the US Government website for trade and commerce, International Trade Administration (ITA, 2008), American Association of Apparel and Footwear (AAFA, 2008), International Labor Organization (ILO, 2008) and resources from Nike’s website (Nike, 2008a; Nike Inc., 2007; Nike, 2008c; Nike, 2008b).

Research Analysis

Outsourcing and Performance

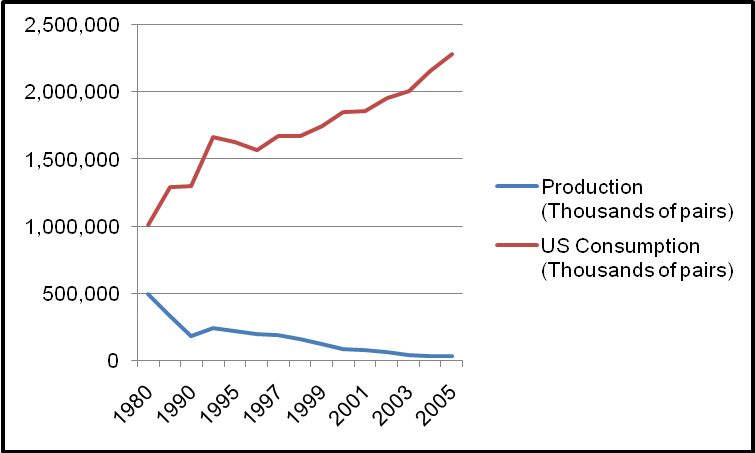

The data analysis is done using both qualitative and quantitative tools. The data collected from the US official websites are analyzed in the following sections. We see that there is a trend of increasing consumption rate and a declining production rate. This leads us to the conclusion that domestic demand was being fed by imports of footwear. Further, we see that there was a decrease in the number of factories in the US as more and more factories were being closed. In 1998, alone 15 footwear manufacturing factories were closed. This shows that there is an increasing trend of shifting the production base from the US market to international locations. Clearly, this finding is supported by the findings of previous studies on the US footwear industry (Donaghu & Barff, 1990; Hadjimichael, 1990; Frenkel, 2001).

Figure 3: Production Consumption Pattern of Footwear in Us. Source: American Apparel Footwear Association 2007Further if we do a correlation study of the US consumption of footwear, total industry turnover and the turnover of Nike over the period we see that that as the turnover of the industry increased, so did the turnover of Nike, whereas the production in the US declined. A correlation analysis of the three variables i.e. the annual turnover and gross margin percent of Nike’s key financials since 1999 to 2006 to the overall production of shoes in the US is shown in table 1. This shows that Nike’s turnover and overall production of footwear and Nike’s revenue are moving n different directions. The correlation between the two is -0.82. This shows that as the production of footwear in the US fell (also refer to figure 3), the revenue of Nike rose. Further, the gross profit margin (%) also rises with a decrease in the overall production of footwear.

Hence, it shows that there is a negative relationship between footwear production in the US and the revenue and profit margin of Nike. With an increase in consumption (figure 3) of footwear in the US, it can be implied that the production in the US actually declined but the market was fed by footwear through imports or outsourced production by domestic companies. This point can be verified by correlating the import of footwear over the period to that of the US consumption which gives a negative correlation of -0.88. But when we correlate US consumption to Nike’s revenue and gross profit margin over the period, we get a figure of 0.99 and 0.96 which indicates that there is an increase in the consumption as well as the sale and profit of Nike. Thus, this shows that the growth in Nike can be attributed to a great extent to an increase in consumption in the country. On the other hand, we see that Nike’s production base was shifting more and more to international locations (Donaghu & Barff, 1990; Baudisch, 2006b).

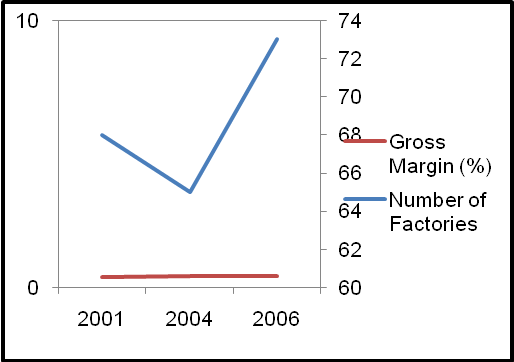

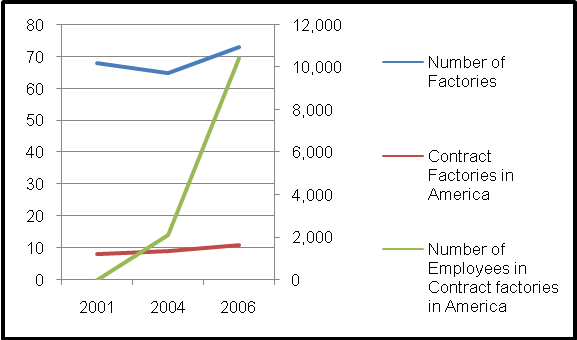

On analysis the data that we derived for the company’s contract factories from the three corporate responsibility reports of the company, we see the number of factories of Nike increased over the years 2001 to 2006 by 7.3 percent and the percentage of factories in three regions i.e. Americas, EMEA (Europe and allied areas) and Asia. The increase in the percentage of shows that Asia has the largest share of Nike’s footwear factories globally and America the least. Further, the share of the percentage of American countries in the share of footwear factories has gone up as opposed to the overall footwear production in the US which has gone down. So we may conclude that the case of increased production of footwear in the US has gone down in the whole industry but not in the case of Nike. But when we see the absolute figures of the number of factories, we see that the maximum numbers of factories are in Asia and the maximum numbers of employees are in Asian factories. So it can be concluded that the maximum production occurs in the Asian countries and the domestic market for footwear in the US is fed by shoes procured from Asian countries.

Figure 4. Source: 1. Nike Inc. 2. American Apparel and Footwear Association.

Figure 5. Source: 1. Nike Inc. Corporate Responsibility report.

Now we have seen that as Nike’s outsourcing of tits manufacturing functions increases so does its gross profit margin. The correlation between eh two is 0.3 which indicates a positive increase in both the two. Further, a graphical view of the two as shown in figure 4 shows that both gross profit margin and the number of factories increase in Nike’s case. This implies that as the outsourcing of the core operations of a business goes to the third party and with an increase in the international outsourcing increases so does the company’s profit margin.

A similar situation can be seen from the industrial data too. As figure 5 shows that with an increase in the import penetration of the imported goods in the US market, turnover of the industry increased showing better performance. Further, we see that the industry’s growth follows a similar pattern with an increase in import penetration in the US market. This signifies that it is actually the US companies who are importing more footwear into the market to meet demand and reduce domestic production.

Thus, both micro and macro data show that as outsourcing operations increased in the US footwear industry, both the industry and the company (Nike in our example) posted better performance. Hence, our findings from the literature (Baudisch, 2006b; Hadjimichael, 1990; Jones & Kierzkowski, 1990) showed that outsourcing improved performance holds true in our study.

Outsourcing and Cost of Production

In this section, we will do a cost benefit analysis of Nike by comparing the cost of production of a pair of shoe by Nike and the average cost of production of the pair. We consider the cost of production of a typical shoe for Nike. There are three basic steps in the production of a shoe, and in the costs associated with those steps. In the first stage, Nike designers and developers produce the design and technical specifications. That information, along with other factors like the volume of shoes to be produced and the length of the production run, are used to negotiate a price (called FOB, or freight on board) between Nike and the supplier factory. The typical athletic shoe has 45–55 components, which are manufactured in 6–10 countries, and shipped to the producer factory. These materials usually account for 60–70% of the cost of the shoe.

Figure 7: Nike’s Cost Breakdown of a Typical Pair of Shoe

Step 1/Step 2

Step 3. Source: Nike Inc. CSR Report 2001

Wages, overhead, depreciation and factory profits account for the rest. The factory produces the desired quantity of shoes and sells them to Nike at the agreed-upon FOB price.

After Nike takes delivery, the shoes are shipped to markets literally all over the world. Along the way, Nike pays for shipping, insurance, duty, and sometimes inland freight, and sells the shoes to retail customers. Losses through theft and damage (shrinkage), insurance and profits, and arrives at a retail cost, which the consumer is then asked to pay. This set of numbers varies between shoe models and is based on demand, the quantity of production, technical complexity, distance to market, competition pricing, and a host of other factors. Basically, the 1-2-4 formula holds true: for every dollar of FOB cost, the buyer (in this case, Nike) charges $2 to the retailer, and the retailer charges $4 to the consumer. The formula is relatively consistent in the industry, and is not markedly dissimilar in apparel and other consumer products.

That wholesale price also factors in costs associated with running our business, including the research, design and development costs, basic administration, marketing, and taxes. The retailer in turn adds on costs associated with staff expense (the largest single factor in the whole chain from beginning to end), rent, promotional investments, losses through theft and damage (shrinkage), insurance and profits, and arrives at a retail cost, which the consumer is then asked to pay. This set of numbers varies between shoe models, and is based on demand, the quantity of production, technical complexity, distance to market, competition pricing, and a host of other factors. Basically, the 1-2-4 formula holds true: for every dollar of FOB cost, the buyer (in this case, Nike) charges $2 to the retailer, and the retailer charges $4 to the consumer.

So one of the prime costs of Nike in the production supply chain is labor cost as shoe manufacturing is a labor-intensive production process. Now if we assume that the cost of production as shown in the CSR Report of Nike is that of China (China consists of more than 50 percent of the company’s production), the factory cost in table 3, which we assume to be solely labor cost is $6, which in US standard is almost 36 times less (ILO, 2008). Clearly then the factory cost would have increased by 36 i.e. it would have become $216. So if we keep other costs constant the product cost would have become $210 dearer. Applying the simple rule of demand and supply, with an increase in the price of the product, the demand for footwear would have gone down, especially when we see that footwear had become a luxury in the post-1970s era. This would have reduced the overall demand, and thus the profit of the company. Hence, outsourcing benefited the company (Nike) as well as the industry.

Outsourcing and Labor Employment

Figure 9 shows that with increasing growth in the US footwear industry there was a declining trend in the employment of the production employees in the plants of the US footwear manufacturers. Thus it clearly indicates that as the industry grows there is a decline in the engagement of employees and hence a reduction in the daily wage of the laborers.

Figure 8. Source: American Apparel and Footwear Association

But the trend is not the same as in case of Nike. Nike has seen an increase in the number of contract factories from 2001 to 2006 in America and there has been an increase in the number of labor employed in the contract factories of Nike in America. As shown in figure 10, there has been an increase in the number of contract factories in America as well as the number of employees in contract factories in the country for 2001-06. This clearly indicates that in this instance the micro data regarding Nike’s contract employees did not hold true with the macro findings of our analysis.

Outsourcing and Supply Chain

In the literature review, we have already described a traditional supply chain for the footwear industry. Here we will trace the supply chain of Nike wherein we will show a transition that the company’s chain underwent since the 1980s. in the mid-1980s Nike had relationships with 60 individual factories around the world—a result of doing business with over 200 factories over the years. At this point, Nike reexamined its sourcing strategy. Maintaining relationships with a large number of factories was costly, as was the constant turnover among suppliers. Nike decided to narrow its suppliers down to a small group of manufacturers that had the necessary capabilities in rubber production, mould, and tool making, and the labor force and management experience to become a long-term production partner. Nike also concluded that it should concentrate on five Asian countries for its production: Korea, Taiwan, China, Indonesia, and Thailand. The core group of suppliers (two Korean, two Taiwanese, one Indonesian, and one Thai company) was encouraged to expand its production in the target countries.

Nike acknowledged that maintaining a core group of long-term partners was not a low cost strategy, but Nike gained speed of delivery, quality, and the ability to manufacture innovative products. The relationships between Nike and its production partners were based largely on trust. Supply contracts did not guarantee specific volume purchases, but Nike always tried to schedule production so as to use its partners’ factories as efficiently as possible. Nike also worked with its partners to estimate the production volumes several years ahead so that the partners could plan their facilities accordingly.

As costs rose in South Korea and Taiwan, Nike and its subcontractors in those countries started to look for opportunities for the companies to continue to supply Nike, but with shoes produced at a lower cost than in their home countries. Indonesia, one of the target countries, begun to aggressively attract foreign investors in the mid 1980s, and Nike’s manufacturing partners were quick to respond. A few years later, Vietnam opened up to foreign investment, and the South Korean and Taiwanese companies soon established manufacturing facilities there too.

Supply chain that creates value is important for the industry. Further, this analysis will provide a detailed understanding of the supply and value chain of the industry and that of Nike. The industry supply chain had been depicted in figure 1. Here we try to trace the supply chain of the brand which would show a blueprint of the US footwear industry’s outsourcing value chain.

Conception/design

The blueprint of a Nike Shoe originates from the Nike Research Lab located at the Nike World Headquarters in Oregon (Nike, 2008a). At the Nike Research Lab, researchers carry out various tests in biomechanics, physiology, sensory in order to customize the product to suit the best interest of the clients. In addition, various factors such as geography, age, gender are also taken into account in order to cater to appeal to the preferences and needs of different segments of the market. For example, according to the Lab, runners in the United States prefer hard surfaces while those in Europe prefer trails and thus this will affect the compositions of the footwear sold in different regions. The latest innovation of the Research Lab, the NikeFree Shoe enhanced overall athletic performance by stimulating the effect of running barefoot with added features that enabled the strengthening of muscles and lowered the risk of injuries (Nike, 2008a).

In an increasingly competitive market with strong rivals such as Reebok, Adidas, Nike’s latest strategy is offering consumers the shoes they desire. This is done by providing customers with the option of designing their own shoes. This further strengthens brand loyalty as consumers develop a further attachment to the brand when they are self-involved in the design of their footwear.

Production

Nike subcontracts the production process of its footwear to 900 contract factories located worldwide with Asian developing countries such as China, Indonesia and Vietnam accounting for the bulk of total world production (Nike, 2008c). Production of the footwear is based on a vertically integrated model. In the primary stage, raw materials such as rubber, leather and plastic are extracted from places located in close proximity from the factories. In the secondary stage, the extracted resources are sent to the factories or “Sweatshops” for manufacturing. It should be noted that the whole production process of Nike footwear is being carried out by independent private contractors.

In these sweatshops, workers are generally offered low wages with little nonwage benefits. In certain factories, workers have been denied a “living wage” as their take-home pay has been insufficient to satisfy basic standards of living. Typically, in these countries, the minimum wage laws were violated and workers were weakly unionized to bargain for higher wages. For example, a typical Chinese worker earns a wage of Rmb$250-$350 while the minimum wage was supposed to be Rmb$350 (Kwan, 2000)

In addition, labor control is exercised harshly in these factories. The measures to minimize soldering manifest themselves in the extreme case where line workers are required to satisfy daily production quotas. Failure to meet daily targets would mean that the individual worker has to work overtime without additional compensation. Besides requires the workers to work long hours each day, management will insist that workers work up to seven days a week with few days off every month. In fact, some of these unethical standards have been indirectly influenced by Nike when the corporation set unreasonable delivery deadlines and low prices for the various batches of products. Indeed, critics have mentioned that the resulting unfair labor practices were in conflict with Nike’s Code of Conduct (Nike, 2008b).

In general, subcontracting the production component of its supply chain to various low-cost regions has enabled Nike to maintain high profits. Subcontracting its production process instead of direct capital investment in a particular place has offered Nike the flexibility of relocating its production easily to places that had the least cost of production. In the 1960s, Nike used to subcontract the production process to factories in Korea and Taiwan. When wages of these countries rose in the 1980s, Nike switched to rapidly developing nations of Indonesia, Vietnam and China which offered low-wage labor (Kwan, 2000). The spatial division of labor takes on a dynamic pattern as Nike constantly reallocates its contracts to places that offer the lowest cost.

It is important to note that although various low-valued functions such as the production process are being contracted out to the periphery, important and high-value functions such as the Nike Sports Research Lab remain centralized at the core.

Marketing

One of the reasons that can explain Nike’s success in the footwear industry is its ability to establish and draw interconnections between its products with the various popular sports and this has enabled it to influence youth culture significantly. That had been carried out through celebrity endorsements, especially by players like Michael Jordan, Thierry Henry, Ronaldo. By featuring prominent players in its advertisements, Nike’s strategy has been seen as a continuous effort in relating individual athletic success to its sports products.

In addition, its popular slogan “Just do it” has left a deep and long-lasting influence on American youth culture. It was significant in the 1980s as it came at a time when American youth dreamed that participating in sports could lead to success. This perception was extremely predominant, especially among working-class youth who perceived that sporting success was the key to escape from the poverty trap. As a result, through the sponsoring of black basketball stars with their basketball singlets, sandshoes, that had influenced street fashion as youths dressed up in a similar manner as their idols and thus creating strong demand for Nike products in the process.

Nevertheless, as Nike markets itself across the globe, its marketing strategy has not been accompanied by wholesale propaganda of American youth culture. In fact, Nike tries to reinvent itself in the local context. For example, the marketing efforts in Europe and Asia have been directed towards sponsoring local sports such as soccer and getting local sports celebrities such as Henry, Ronaldo to endorse the products (Nike, 2008c). In Australia, where local culture offers less resistance, Nike advertisements carry a stronger American cultural influence.

Nike has been a prominent icon featured in sponsoring sports teams and several sports events held on a regional and global scale. For example, on a regional scale, it has been an active supporter of the European soccer championships. On a global scale, it has been sponsoring the Olympic Games and the World Cup (Nike, 2008c).

Retail

Currently, Nike operates at least 323 retail outlets worldwide, where almost half of the outlets are currently located in the United States. In 2005, domestic sales continued to account for a significant portion of total revenue. In the US, 12 Niketowns have been established in various cities such as New York, Chicago and San Francisco. As one-stop places, Niketowns offer a huge variety of footwear, apparel, equipment and other sports products as well as information on sports, events and fitness. Beyond the US, Niketowns also has an international presence in major cities such as Tokyo, Berlin and London. Besides having Niketowns serving the major population centers, regional distribution centers have also been established in places like Oregon, Georgia, California serving a larger network of retail outlets across the US. (Nike, 2008c)

So if we have to show the supply chain of Nike it can be shown as the following diagram. As Figure 6 describes, upstream business processes enable compliance in the factory and sustainability in the supply chain. Rules of the game are clear and adhered to. Businesses own compliance and sustainability. Contract factories invest in worker training and development rather than viewing workers as commodities. Internal marketplace builds up, where business is flowing to the best-class suppliers because of their price, quality and corporate responsibility.

Strategic factory partners see the benefits of building strong human resource management systems that ultimately lead them on a journey to lean manufacturing and greater profitability. Waste is minimized and leveraged as a source of income and innovation. Consumers use their purchasing power to incentivize best practices.

As of FY06, Nike’s three main product engines – footwear, apparel and equipment – used almost 700 contract factories in 52 countries to manufacture all Nike products. Through annual reviews of Nike’s supply chain needs, we may add or change contract factories based on product sourcing requirements, changing business and fashion trends, and/or general factory performance. Should a factory be dropped from the supply chain and not receive an order for more than 12 months, it must go through the new source approval process we require of all new contract factories that join our supply chain. Although the workforce profile varies by country and region, the vast majority of the almost 800,000 workers in Nike contract factories are women who are 18 and above. This is the first job for many of these workers, requiring low skills. In many cases, it is also their first introduction to the formal workforce.

Even as the industry matures, many of the manufacturing roles remain entry level and require low skill sets. Others require broader skill sets as we continue to implement lean manufacturing principles throughout our supply chain. At the end of FY06, footwear contract manufacturers in China, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Thailand manufactured 35 percent, 29 percent, 21 percent and 13 percent of total Nike-brand footwear, respectively. The vast majority of Nike-brand apparel was manufactured outside of the United States by independent contract manufacturers in 49 countries. Most of this apparel production occurred in China, Malaysia, Thailand, and Turkey. (Nike Inc., 2007)

Nike follows a lean manufacturing process as many automobile companies (Nike Inc., 2007). It’s a philosophy of delivering the most value to the customer while consuming the fewest resources. Techniques concentrate on the product’s end-to-end value stream rather than traditional functions and organizations. It focuses on the goal of creating the highest-quality product while eliminating all types of waste, including lost time and material. In traditional manufacturing environments, workers typically are trained on one task and represent one step in the process. In a lean environment, workers produce in teams, where they are cross-trained in different skill sets and are more empowered to manage the production process and immediately address quality and other issues.

Historically, the footwear and apparel industries have operated a “push” system, focused on economies of scale, with large batches and long assembly lines. This system relies on labor-intensive manufacturing processes that incentivize manufacturing in low-cost countries. But this model doesn’t translate directly to the new environment, where customers increasingly demand greater variety, more frequent deliveries, and smaller order quantities, all at a lower cost. This is the outcome of the supply chain as the industry has devised due to its policy of completely contracted manufacturing.

Outsourcing and Ethics

The ethical issues that have gained prominence in the case of the footwear industry are the evolution of the concept of sweatshops. This phenomenon is not restricted only to the footwear industry but in all industries where the trend of fragmented international procurement has gained prominence. In the wake of several well-publicized scandals involving child labor, hazardous working conditions, excessive working hours, and poor wages in factories supplying shoes to the Nike stores has gained ground. We do a study of these increased trends of violation of human rights as the industry grew in size. To do this we consider the case of Nike.

Taking Nike’s case, we searched for articles in newspapers and periodicals on Nike (which included all areas of news regarding Nike), articles that spoke of sweatshops of Nike, child labor in Nike factories, and exploitation practices in Nike’s factories. As shown in figure 11, the number of instances of mention of exploitation and/or sweatshop and/or child labor in case of Nike factories increased from 1999 to 2000 but then there was a declining trend till 2006. The main ethical problem with Nike factories that has gained the maximum media attention is the problem of sweatshops. Sweatshops covered 75 percent of all the ethical issue-related coverage in newspapers in 1999, which reduced to 62.9 percent in 2002 and again increased to 65 percent in 2004. The case of child labor in Nike factories is interesting. There was a decline in instances of child labor in 2003 but since then it has increased. The percentage of instances of child labor in Nike factories increases from 2 percent in 1999 to 6 percent in 2002 to 19.9 percent in 2006. This increase in instances of child labor clearly raises the question that if social audits are properly done in the industry’s contract factories?

Doing a correlation analysis on the data from 1999 to 2006 and the gross profit margin of Nike for the same period. The analysis shows that with the increase in profitability of the company over the years there has arisen a positive relationship between gross profit margin and the number of mentions of Nike, child labor in Nike, and all three cases of sweatshop, child labor, and/or exploitation in newspapers. This indicates that with an increase in the gross profit margin of the company, the problem of child labor and overall labor-related and ethical issues and human rights issues intensified in the Nike plants. The problem of sweatshops though shows a negative ratio indicating the reduction in the instances of sweatshops.

Figure 12. Source: Newspaper articles, Nike Inc.

In response to the growing criticisms, Nike created several new departments (e.g., Labor Practices (1996), Nike Environmental Action Team (NEAT) (1993)) which, by June 2000, were organized under the Corporate Responsibility and Compliance Department (Nike, 2008b; Nike Inc., 2007). Last year, in an effort to strengthen the links between production and compliance decisions, the compliance department was moved into the apparel division. Currently Nike has a team dedicated to labor and environmental compliance, all located in countries where Nike products are manufactured. These employees visit suppliers’ footwear factories on a daily basis.

In apparel, given the much larger numbers of suppliers, Nike managers conduct on-site inspections on a weekly or monthly basis, depending upon the size of the firm. In addition to its corporate responsibility and compliance managers, Nike has about 1000 production specialists working at/with its various global suppliers. All Nike personnel responsible for either production or compliance receive training in Nike’s Code of Conduct, Labor Practices, Cross Cultural Awareness, and in the company’s Safety, Health, Attitudes of Management, People Investment, and Environment (SHAPE) program (Locke, Qin, & Brause, 2006). The company is also developing a new incentive system to evaluate and reward its managers for improvements in labor and environmental standards among its supplier base.

In recent years, Nike has pushed its suppliers to obey standards through increased monitoring and inspection efforts. For example, all potential Nike suppliers must undergo a SHAPE inspection, conducted by Nike’s own production staff. The SHAPE inspection is a preliminary, pre-production inspection of factories to see if they meet Nike’s standards for a clean and healthy workplace, respectful labor-management relations, fair wages and working conditions, and minimum working age. After this initial assessment, labor practices are more carefully audited by Nike’s own labor specialists as well as by outside consultants like Price Waterhouse Coopers (PWC). This second audit looks more carefully at the company’s wages, use of overtime, availability of benefits, and age of its employees. In addition to the SHAPE and labor practices audits, all factories are evaluated by Nike’s production personnel on a range of issues like quality, flexibility, price, delivery, technical proficiency, managerial talent, and working conditions. The goal of these various inspections and audits is to sift through Nike’s vendor base and retain only those who meet not only price, quality, and delivery expectations but also labor and environmental health standards.

The company is currently developing a grading system for all of its suppliers, which it will use to determine future orders and thus create a strong incentive among its suppliers to improve working conditions. Nike is also exploring new incentive schemes that will reward good corporate citizenship among both its suppliers (again through increased and more value-added orders) and its own managers. Nike managers are responsible for supplier factories that show improvement in labor practices and health and environmental standards will be rewarded in still to be defined ways. In addition to its own internal inspections, Nike suppliers are regularly audited by external firms like Ernst and Young, PWC and various accredited non-profits that specialize in this work.

In addition to developing internal expertise and capacity in the area of standards and corporate responsibility and working with its own suppliers to improve their performance in these areas, Nike has been active in founding and/or supporting an array of different international and non-profit organizations, all aimed at improving standards for workers in various developing countries. For example, Nike is actively involved in the United Nations Global Compact. Launched in 2000 by UN Secretary General Kofi Annan, the Global Compact seeks to promote corporate citizenship among multinational companies. Companies seeking to join the Global Compact adhere to a set of core standards in human rights, labor rights and environmental sustainability. They engage in a variety of activities aimed at improving these standards in the countries where the MNCs operate.

Nike is also a founding member of the Global Alliance for Workers and Communities, an alliance of private, public, and non-profit organizations that seeks to improve workplace conditions and improve training opportunities for young workers in developing countries. Other members of the Global Alliance include The Gap, Inc., the MacArthur Foundation, and the World Bank (Locke, Qin, & Brause, 2006). Finally, Nike is active in the Fair Labor Association, formerly the Apparel Industry Partnership. Initiated in 1996 by President Clinton, the FLA is an American non-profit organization that seeks to bring together various industry stakeholders to develop a common set of standards and to monitor these standards around the world. Although the FLA has experienced controversy, including the defection of its union affiliates, it has recently begun to sponsor independent audits of the factories supplying its members (Locke, Qin, & Brause, 2006). The results of these various activities have begun to produce some significant changes among Nike suppliers.

For example, as a result of its various inspections, audits and internal research, Nike has been able to virtually eliminate the use of petroleum based chemicals in its footwear production. This is something even the company’s critics acknowledge. Nike has taken the initiative in organizing an industry-wide organic cotton consortium and is making major strides in improving working conditions among its various suppliers. Of course, not all of Nike’s critics are convinced. Many continue to complain about poor wages and working conditions at Nike’s suppliers in Vietnam, China, and Indonesia (Kwan, 2000). Others argue that Nike’s initiatives are simply not enough and that the company could do much more in the areas of wages, working conditions, human rights, and local socio-economic development. Yet the continuing controversy over Nike and its various activities are not in any way particular to Nike. Rather, they are reflective of much broader debates about the definition of corporate citizenship and the process of globalization (Locke R. M., 2002).

A study of the corporate social responsibility report of Nike shows that there is a great discrepancy with the management audit results of the different regions. The M-audits of factories of Nike around the world showed that the primary causes of grievances in most plants of Nike were wage and benefits for the years 2004, 2005 and 2006. Of 42 MAV audits completed in 2006, seven contract factories received an A rating and 13 contract factories received a D rating, the lowest rating we assign to a factory. Ignorance of the law or the Nike standard is a primary driver of non-compliance. A D rating implied that the factory was non-compliant to the management standards of Nike (Nike Inc., 2007). The second-leading issue was a lack of systems to manage people and processes. By assessing factory performance through a root-cause approach, we are better able to identify upstream contributors to problems and drive remediation efforts at the source. Our work in 2005-06 went deep into two topics – wages and hours – and closely examined root causes (Nike Inc., 2007). Further, the report also showed that the compliance ratio was higher in the Americas and lowest in the north and south Asian regions. This confirms the findings of Locke et al. (Locke, Qin, & Brause, 2006).

Clearly, there are ethical issues related to Nike and the emergence trend of contract outsourcing of manufacturing. While considering the stakeholder theory, it must be kept in mind that when the shareholders’ profit is the company’s ethical liability, so is the safety, health and safeguarding the human rights of the company’s employees and suppliers. Internal customers hold equal importance. But at times, due to the drive to increase shareholder’s profit, these subtleties of ethics are foregone by multinational companies like Nike. These issues need to be kept in mind while designing a supply chain based on contract manufacturing to reduce the cost of production.

Conclusion

The U.S. footwear industry in the 1930s has served as an exemplar case of industrial evolution to develop his famous hypothesis about the positive correlation of innovative activity and firm size. At the start of the industry, the provision of production technology and production has been the core node of this industry’s value chain in accordance with the Schumpeter hypothesis. On the other hand, the U.S. footwear industry in the 1980s and 1990s serves Gereffi and his coauthors (1994; 2005) to develop their notion of buyer-driven value chains for their industrial analyses. Finally, Frenzel Baudisch (2006b) shows that U.S. footwear consumption since the 1970s is increasingly driven by social comparison processes. According to the theoretical proposition about the influence of consumer motivations on the nature of competition in the U.S. footwear industry, the core node of the global footwear chain shifts to marketing, product design, and distribution, as the market becomes driven by variety oversupply in the 1970s.

Drawing on Adner and Levinthal’s (2001) model of functional satiation and variety oversupply and on Frenzel Baudisch’s (2006b) theoretical account about consumer motivations to ‘over-demand’ product varieties beyond their functional requirements we propose an explanation for the transformation of the U.S. footwear industry as an endogenous process. We argue that functional satiation effects U.S. demand for footwear and increases the demand uncertainty for suppliers introducing new functionalities. The basic argument is that this increase in demand uncertainty leads to the transformation of the U.S. footwear industry, from being Schumpeter’s exemplar case to being the exemplar case for a buyer-driven value chain in the works of Gereffi and his coauthors. When the functional requirements of consumers are met, their marginal utility for further product varieties decreases.

When a market gets functionally satiated, this lead to the simultaneous competition with respect to innovations and prices, as the producer cannot decrease price competition by introducing new product varieties any more. The organizational separation of the processes of product innovation and manufacturing into different firms provide specialization and greater economies than when integrating both processes infirm. The separation of product innovation from manufacturing is made possible as the firm’s competitive advantage is built on its capacities to organize its value chain and not by its capacity to actually produce goods. The organization of the value chain aims at the reduction of lead times in order to increase the lead firm’s ability to react to unforeseen demand shifts, which are independent of the product functionalities, like in herding behaviors or fashion cycles.

Functional satiation occurs when the functional requirements of consumers with respect to particular product characteristics are met. This leads to simultaneous price and innovation competition and increases the demand uncertainty for suppliers with respect to product functionalities. In such a competitive market situation the firms’ capacities to organize the provision, sourcing, and production of goods becomes more important than their technological or productive capacities. In this sense, we have argued on the basis of the transition of the U.S. footwear market that functional demand satiation leads to the separation of product innovation and manufacturing and the modular organization of an industry’s supply chain. We theoretically integrate demand effects to explain industry dynamics, i.e., to explain the endogenous process of industry organization from a highly integrated and concentrated industry that is an exemplar case for the Schumpeter hypothesis to being a buyer-driven global supply chain.

In terms of corporate citizenship, there is significant debate over the responsibilities of corporations. Should companies behave solely to enhance shareholder wealth, or should they act to benefit other groups (both within and outside the firm) as well? Should corporate decision-making be driven solely by economic considerations, or are other (social) factors equally important? How does one measure and account for these other considerations? Are corporations responsible only to their own employees and shareholders, or are they also responsible for the employees of their suppliers and subcontractors? What are the boundaries or limits of any individual company’s responsibilities? Given that there are no universal standards and that not all companies are promoting labor and environmental standards as rigorously as Nike is, how does one promote greater coordination and collective action among major producers? If some companies promote and monitor for higher standards and others do not, does this erode the competitive edge of the “good” corporate citizens?

A related set of questions and divergent views characterize debates over globalization and its consequences. Should multinational companies abide by so-called international labor and environmental standards, or is this simply regulatory imperialism and de facto protectionism in another guise? Will the imposition of these standards on developing countries diminish their competitive advantage and thus damage their economic development? Or will improved labor and environmental standards lead these local producers to upgrade their production processes and up-skill their workforces and thus enhance their long-term competitiveness? Who (which actors) should be responsible for developing these standards? National governments, international organizations, transnational non-governmental organizations, local trade unions and civil society groups or even individual corporations (through their own Codes of Conduct)?

The standards (if any) which are implemented and the actors who set the standards will have dramatic consequences on the future trajectory – and the relative winners and losers – of globalization. Thus, it should come as no surprise that these issues have provoked so much controversy and debate in recent years. These questions – and how they are answered – will shape the future of international management for many years to come.

Thus, the research clearly shows that increased fragmented international outsourcing is beneficial to the shareholders as it increases the production of the industry as well as the company. It provides a cost-effective production opportunity through which prices in the market of products can be reduced. But the question that the study of the ethical issues arises is that how far are they good for the entire stakeholder of the company and the industry? This area needs to be studied in greater detail and can be stated as one of the limitations of our study.

Works Cited

AAFA. (2008). US Footwear Trend Statistics. Web.

Abernathy, F., Dunlop, J., Hammond, J., & Weil, D. (1999). Lean Retailing and the Transformation of Manufacturing – Lessons from the Textile and Apparel Industries. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Amsden, A. H. (1989). Asia’s Next Giant. Oxford University Press.

Baudisch, A. F. (2006a). Continuous Consumption Growth Beyond Functional Satiation. Time-Series Analyses of U.S. Footwear Consumption, 1955 – 2002. Max Planck Institute of Economics, Evolutionary Economics Group: Papers on Economics and Evolution, #0306.

Baudisch, A. F. (2006b). The Emergence of the Global Value Chain for the U.S. Footwear Industry. Jena, Germany: DRUID Working Paper No. 06-3.

Borsodi, R. (1929). The Distribution Age. New York: D Appleton & Co.

Camuffo, A., Furlan, A., Romano, P., & Vinelli, A. (2005). Breathing Shoes and Complementarities: How Geox has rejuvenated the footwear industry. Cambridge, MA: MIT IPC Working Paper IPC-05-005.

Cheng, L. (2001). Sources of Success in Uncertain Markets: Taiwanese Footwear Industry the Challenge of Flexibility in East Asia. In R. D. F.Deyo, Economic Governance and (pp. 33-53). New York: Rowman & Littlefield.