Introduction

All nations across the world face the problem of obesity. In the UAE, the availability of high-energy and sugary foods, unsafe physical activities, and genetic predisposition makes the disease a prevalent health challenge across all population segments. This situation underlines the need to develop and implement a health promotion campaign to address it. This paper presents an obesity health campaign that targets 6 to 18-year-old children in the UAE.

Justification for the Choice of the Health Problem in the UAE

Nations across the world continue to record high prevalence rates of obesity among school-going children of all ages. For example, in Gulf countries, Alnohair (2014) informs that children between 6 to 18 years have a prevalence of overweight ranging between 16% and 17%. In the UAE, an intervention strategy for childhood obesity, especially among the 6 to 18-year-old population segment is incredibly important.

The health problem is a major pandemic that influences health outcomes for children in the UAE. AlBlooshi et al. (2016) find an alarming rate of childhood obesity in the nation. For those aged 15 to 18, about 3% of girls and 10% of boys show evidence of extreme obesity (AlBlooshi et al. 2016). Therefore, in the UAE, choosing a health communication campaign that focuses on obesity as a major health problem that is prevalent among 6 to 18-year-old children is important and justifiable.

Overview of the Importance of Health Communication

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2016) informs that obesity is a risk factor to other health challenges, including hypertension, type-2 diabetes, stroke, impaired mental health, and sleep apnea. Therefore, a health communication plan can help to minimize its prevalence levels in the UAE. Such an intervention should address the underlying causes of obesity, including the environmental and individual-level factors that promote the development of obesity in the UAE.

As a result, an obesity communication campaign in this region can help to inform parents and other care providers such as teachers about the appropriate measures that can address environmental and individual-level factors, which increase the risk levels of obesity among 6 to 18-year-old children in the UAE. However, a health communication campaign cannot establish policy frameworks for addressing obesity. It can only bring the health problem into public attention to persuade the UAE’s Ministry of Health (MoH) to take the necessary action.

Steps of Healthy Communication Campaign Development

The process of developing a health communication campaign consists of twelve steps. The first step, project management, bears the meaningful planning of the mechanisms for stakeholder engagement. For the case of the UAE, this step will entail setting decision-making processes, work plan timelines, and the campaign duration. The step will also include the allocation of materials, personnel, and financial resources.

Promotion strategy development entails making considerations for measurable objectives at all four levels (individuals, networks, organizations, and communities/societies) and ensuring they are pragmatic, comprehensible, explicit, have premeditated precedence, quantifiable, achievable, and time-bound (Public Health Ontario 2012, p. 51). In this phase, an assurance of awareness and supportiveness of all project teams in the strategy of health promotion is determined.

Here, narratives coupled with different logic models are deployed in strategy description. The third step entails the analysis of the audience. For example, a communication campaign developer will gather the demographic, psychographic, and behavioral traits of the selected UAE audiences (6-18-year-old kids) before developing their profile.

In the communication inventory step, one lists the various communication resources, which are readily available within the community and in the organization. This list should also include good relationships and any existing alliances. Step 5 involves the identification of bottom-line alterations that one seeks to realize. One accomplishes this step by describing the change, as opposed to actions. It entails ensuring that objectives obey the SMART criteria.

In step 6, a health campaign developer chooses channels and vehicles, which he or she deems the most appropriate for a particular situation. A decision is made based on factors such as the capacity to reach the target audience, effectiveness, and cost. Public Health Ontario (2012) recommends the blending of long-lived and short-lived vehicles and channels. Step 7 involves sequencing and combining the various tools identified in step 6 over and across timelines. As an example, holding big events in the UAE while launching the campaign and considering a grand finale will help to create massive awareness. It will be important to link the campaign with huge activities or issues that attract public attention and agenda in the country.

Message strategy development (the eighth step) addresses the specific information to be delivered, including how to say it to the identified audience. Identity development constitutes step 9. It involves creating distinctiveness, which can communicate the intended image and one’s desired relationship with spectators. Here, one can use logos, images, and position statements that may help in identity creation. Step 10 demands the proportion campaign developer to produce the best materials under strict compliance with budget and time constraints. It also entails the pre-testing of the materials with the desired audience before the campaign implementation in step 11.

Evaluation forms the last step. It involves gathering, interpreting, and acting upon various quantitative coupled with qualitative materials together with the information generated in all 11 steps (Public Health Ontario 2012). Hence, this step cannot be implemented separately since it cuts across all other stages. It helps in reviewing each phase to eliminate potential drawbacks, which can be replicated in subsequent steps.

Application of the Steps in Developing a Contextualized Health Campaign for the Problem

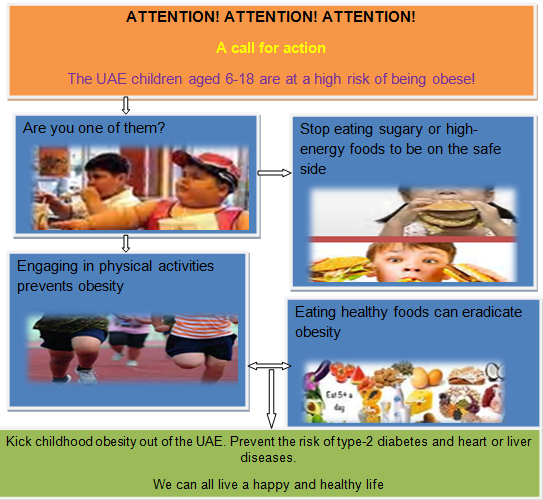

The project is scheduled for implementation from January 2018. It is expected to run until July 2018. It targets 50 sampled schools in Dubai. The work plan is to prepare promotional materials with images of overweight children stuffing junky foods in their mouths, which will indicate childhood obesity as the outcome of their actions with the help of flow diagrams. The project requires USD 100000 mainly to be utilized in paying people who are involved in its project execution, including purchasing healthy food alternatives for a demonstration to parents, children, and teachers who are the main stakeholders in the campaign.

Approximately USD 5000 will be spent on transportation and buying refreshments for the project team workers. An additional USD 10000 will be utilized in producing materials such as charts similar to the one shown in Figure 1. A further USD 20000 will be allocated to purchasing hardware and software necessary for data collection, analysis, and management of a call center. The project team consists of a director, an assistant director, a health nutritionist, a chauffeur, three data analysts, and a call center manager.

The project team will launch its campaign in the sampled schools during festivals or official parents’ visits. For example, beginning November 9 to 18 this year, the UAE will hold the Abu Dhabi science festival, which is an important event for launching the campaign. The nutritionist selects the time for the delivery of his or her message in a manner that it is opportune to create the most desired image and identity. This step should immediately follow when the targeted audience (6 to 18-year-old children) has eaten its meals. This strategy allows for making comparisons between what one has eaten and what is being promoted as a healthy eating habit. Thus, the audience can effectively identify with the message carried in the promotional materials.

After the health nutritionist finishes his or her address, the rest of the project team members distribute the promotional materials alongside the 24-hour contact details of the call center (based in Dubai) for those who wish to seek additional help to aid in adopting better eating habits and physical activity interventions for their children. After seeking permission from parents and teachers, the project team returns to the same schools two days later.

The team requests students to take part in weight tests to determine their likelihood of being obese. It keeps the data for future analysis. In the last month of the campaign, the team returns to collect data on the change of food preferences in the school cafes. It also measures the weights and any other necessary parameter again for the calculation of BMI for students who participated in earlier tests.

The Contextualized Message Communicated in the Campaign

Gornall (2016, para. 7) asserts, “Research shows that obesity is on the rise among the UAE’s children, with grim consequences not only for their health and happiness but also for the economic future of a country facing ever-increasing medical costs”. Eating habits, lifestyles, genetic predisposition, environment, and metabolism explain this turn of events. Consequently, a health promotion communication intervention needs to address these issues. The contextualized message in Figure 1 below addresses childhood obesity among six to eighteen-year-olds. The message insists on the need to stop poor eating habits. It also sensitizes the targeted audience (parents, teachers, and children) on the need to adopt healthy diets, especially fruits and vegetables, while participating in physical activities.

Theoretical Framework for the Health Message

The health message used in this case is founded on the social-environmental theoretical framework. The choice of the framework stems from the primary concern of the messages. For example, the messages do not focus on individual health outcomes associated with childhood obesity in the UAE. Rather, they focus on population-based approaches to childhood obesity eradication and management for 6 to 18-year-old kids. In such a context, an important approach encompasses the social-environmental framework.

The framework is important where the obesogenic environmental concept coupled with its implication to the obesity case of the target population is acceptable. In such a context, it is critical to consider models that incorporate socio-cultural and economic policies. However, Kelly et al. (2013) advocate for the need for considering behavioral and psychosocial factors in any health promotion model. The messages target environmental change as a way of promoting population behavioral change. In this context, the theoretical framework deployed in the research complies with the theory on health promotion.

The Key Indicators to Evaluate the Success of the Campaign

The key indicator of the health campaign before the campaign entails the lifestyle habits in target schools. This indicator focuses on the composition of diets taken by children in schools during lunchtime and the level of physical activity. The choice of the indicators is influenced by the argument that the increased rate of childhood obesity prevalence in the UAE arises from the rapid increase in high-energy intake from take-away foods from home and at the school cafes (Kothandan 2014).

The largest proportion of caloric consumption derived from fast-food restaurants relates to the bigger portion sizes, higher convenience, accessibility, and affordability (Kothandan 2014). Therefore, if the analysis of data collected from school cafes on the change of food preferences shows a shift to more healthy food alternatives, this observation will be a key success indicator during the campaign.

Fast foods are closely associated with higher calorific intake, fats, poorer nutrient consumption, higher sodium intake, and an elevated BMI. Hence, these elements correlate positively to the higher cases of childhood obesity. The situation becomes worse where children engage in less physical activities. The number of parents calling to seek more information on the appropriate food alternatives to fast foods and the requisite physical activities for optimal weight loss for their child will be a success indicator during the campaign.

At the end of the campaign, the project team will revisit all 50 schools to collect data on weight relative to the acceptable BMI ratings for each student who participated in the earlier tests. Reduced weight about the acceptable levels in many of the students will be viewed as a success indicator of the campaign.

Conclusion

The lucrative position taken by the UAE in its oil production comes with some challenges. It has led to a meteoric economic growth and development. The situation has created a society that lives in a less physically demanding life characterized by cake-stoked cafes at many points. The outcome is overweight and obese society. The paper has developed a health promotion campaign addressing the problem. The campaign targets 6 to 18-year-old children in the UAE.

Reference List

AlBlooshi, A, Shaban, S, AlTunaiji, M, Fares, N, AlShehhi, L, AlShehhi, H, AlMazrouei, A & Souid, A 2016, ‘Increasing obesity rates in school children in United Arab Emirates’, Obesity Science and Practice, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 196-202.

Alnohair, S 2014, ‘Obesity in Gulf countries’, International Journal of Health Science, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 79–83.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention 2014, Obesity prevention. Web.

Gornall, J 2016, ‘The bulk of the problem – dealing with childhood obesity in the UAE’, The National. Web.

Kelly, A, Barlow, S, Rao, G, Inge, T, Hayman, L, Steinberger, J, Urbina, E, Ewing, L & Daniels, S 2013, ‘Severe obesity in children and adolescents: identification, associated health risks, and treatment approaches: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association’, Circulation, vol. 128, no. 15, pp. 1689-712.

Kothandan, S 2014, ‘School based interventions versus family based interventions in the treatment of childhood obesity-a systematic review’, Archives of Public Health, vol. 72, no. 1, pp. 1-17.

Public Health Ontario 2012, Developing health communication campaigns. Web.