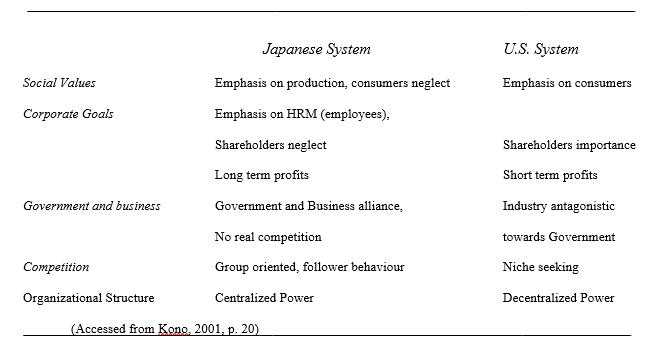

Corporate philosophy and strategies comparison between the U.S. and Japan

With the advent of the word ‘Americanization’, management ideas and practices started evolving and influencing other nations of the world. However, there still is no doubt that during the 1970s and 1980s, Japanese firms under ‘capitalism’ type of Japanese Management System achieved better performance than their American competitor, counterpart and teacher. Japanese firms differed characteristically from the latter in such areas as owner-manager relations, industrial relations, inter-firm relations and business-government relations (Fukada & Dore, 1993).

Ironically, from the start of the 1990s, just after the Japanese Asset Price Bubble (1986-1990) era, firms and capitalism in Japan deteriorated in their performance. They then again found themselves under the influence of the United States, this time they named it ‘Re-Americanization’. Initially the 1990s for the Japanese Management System was followed by the imitation of American business and capitalism which extended to all functions of Japanese firms and all aspects of capitalism. At the individual firm level, it was pronounced in owner-manager relations as ‘shareholder value’ and industrial relations as lay offs, in corporate finance, accounting practices, corporate governance, etc.

Japanese fields which adopted U.S- style capitalism were the finance and insurance sector, business philosophy, business education and consulting. The principal routes for these types of rising influences were direct investment and multinational firms, but these were not all. Trade, technology tie-ups in collaboration with licensing agreements, advertising, visits, consultancies and diverse other routes exist; we may also add indirect investment, currency and financial policy, and, recently, economic policy.

Especially after the large wave of economic Americanization had ebbed, Japanese characteristics became manifest in business management and technology. Own types of business management and systems of production technology, different from those of the USA and from the previous indigenous ones, established themselves. They emerged together with different types of political as well as industrial relations.

Thus, after a period of incorporating American ideas, behaviour and values, their own and new types of capitalist systems took shape during the 1970s in Japan. These types of capitalist systems include the one later known under the brand name of Rhenish capitalism in the case of Germany, which entered into serious (possibly terminal) crisis after the reunification of the two German states in 1990 and in the following decade. The so-called Japanese style of management lost its way soon in the bubble economy and therefore had to have changed the management style. Of course these types could not be viewed merely as a return to tradition. These German and Japanese versions were largely a transformation of American models. They emerged under the impact of, as well as in contest with, American models (Kudo et al, 2003, p. 25).

Pros and Cons of the Japanese Management System

Being too much ‘American’, Japanese management was condemned and shunned for adopting outright American style of management in the 1990s. However after the decline of the Japanese economy, the financial institutions adopted a new and unique method of dealing with fiscal crisis, which in the long run failed to overcome the decline in Japanese growth rate. The value of the land assets that were used as collateral for bank loans has diminished sharply.

The world of e-commerce flourished since the bubble economy collapsed in the early 1990s and Japan appears to be lagging behind the US in its development. Although in some areas of Tokyo, such as Shibuya, the new economy started emerging. At the turn of the century it was realized that Japan accepted its defeat as a nation in decline rather than ascendancy, as in the 1980s.

Long term Goals vs. Short term Profit

Apart from the declining economy, today’s successful Japanese corporations are inclined to emphasize long-term goals and have a global vision, while US corporations put more emphasis on short-term profit. Japanese firms develop their goals emphasising upon long-term growth rather than short-term profits because consideration of the interests of shareholders is minimal compared with that of banks and employees: long-term growth increases the promotion opportunities for employees and investment opportunities for banks. The banks exercise what Murphy refers to as ‘credit rights’ (Murphy, 2000, p. 36).

According to research and statistical data, about 80–90 per cent of large Japanese corporations engage in long-term planning, whereby they plan how they will grow or rationalise over a period of five to 10 years. They invest heavily in research and development: for example about 10 per cent of the sales is invested in R&D at Sony, Matsushita, Toshiba and Hitachi. According to a survey of 205 manufacturing companies, average R&D spending was about 4 per cent in 1995, a level consistent with the achievement of long-term growth rather than short-term profits (Kono, 2001, p. 14). Japanese companies in seeking long term profits invest a large proportion of their resources in the production of technology-intensive products, while American firms invest in short term profits, thereby upholding a minimum risk.

Japanese Corporations emphasize upon important values of the corporation, for example ‘Sony thrives on exploring the unknown’, while Matsushita promises that ‘the company will provide home appliances at a reasonable price, like the supply of water’. These long-term goals and clear corporate philosophy and vision have a great impact on corporate strategy. In part they contribute to the outstanding capacity for sustained corporate action that originates in a special conception held by Japanese corporations, a conception illustrated by the tendency of employees to speak of ‘our company’, meaning that the company is not only an organisation of employees but also an organization for employees.

It is said that Japanese firms are competition-oriented due to long-term growth and market share, in fact they does not follow any competition, but is a part of their goals. Forming business groups and follower behaviour influenced by the social factors is another negative characteristic of the Japanese economy which welcomes all kinds of business groups like vertically integrated groups, weak, cooperative, horizontal groups.

It would be better to say that the top Japanese management consider their national firms in the same field as rivals. For this purpose Japanese firms grow in a particular field, rather than to stay and grow in a niche. On the other end, there is no room for any groupings or lobbies in the American Management system. All it believes is the ‘niche’. Typically, Japanese corporations prefer to form alliances than to acquire additional companies and therefore work in groups.

Centralization

Despite so many vulnerabilities, Japanese corporations respect their workers. Of course they have no option other than to respect their workers as they don’t have ‘bidding’ system or hire and fire system. The reason is Japanese managers do not afford to loose their ‘low-paid’ labour. For this reason they are unable to distinguish between blue and white-collar workers. Companies seek to retain such workers by providing a career with the firm, while the workers are in turn motivated to stay with the company until retirement age. It is this system that enables a Japanese company to become a learning organisation. The company can emphasise training, and employees can be rotated to gain a broad knowledge base during their long years of service.

U.S human resource does not believe in training or updating their staff as it is easier for them to find one capable employee after the ‘obsolete’ one, after all American managers offer handsome wages, for their labour is not that cheap. Workers are employed for certain jobs only, for which they have been trained elsewhere, and training is not provided by the company. Employees are easily laid off when the operation needs to downsize, and they move from one company to another in pursuit of better wages or job opportunities. In the Japanese corporation flexibility is not achieved at the expense of core employees but by means of the many part-time, seasonal and subcontracted workers that the large corporations employ and retrench as required.

Competitive Strategies

With respect to competitive strategies, Japanese corporations were extremely competition oriented because of their copycat behaviour. To cope with the competition, what Japanese firms did was the usage of vertical and horizontal alliances and mergers to reinforce capabilities. Alliances which the Japanese firms use are classified into three types: contract alliances and joint ventures based on combined strength; horizontal and vertical alliances based on the different skills offered by the partners; and alliances where different development, production or marketing processes are combined. Example is that of Hitachi and NEC, once rivals in the semiconductor business, decided to cooperate in the development of large-memory semiconductors, as did Toshiba and Fujitsu.

Once the Japanese organisational structure used to be highly centralized but recently after being a victim of critics, degree of decentralization has occurred. This has ‘internalized’ many companies. Hitachi has been able to establish ten such companies, each headed by a president. Sony has set up four companies of this type. Hitachi previously had a strong head office that housed marketing and other key functions.

Japanese government policy has typically put more emphasis on production than on consumer welfare. Japanese goals are formulated on long-term growth while Americans build on short term profits. Japanese firms’ investment strategies emphasizes upon research and development and proper employee training. Sony and Canon spend about 10 per cent of their sales receipts on research and development (Kono, 2001, p. 195). No doubt Japanese goods today are a symbol of quality for they are more quality oriented than U.S, but then again Japan must have to consider other aspects of production in which it is vulnerable.

On the other end Americans emphasizes on less capital investment. Japanese firms’ maintain good cooperation relations between suppliers, manufacturers and vendors while American organizations believe in open bidding systems and independent sales channels. This is the reason for why Americans suffer due to long development time and large inventory. Extensive and effective cooperation exists between assemblers, component suppliers and sales channels, irrespective of whether or not the assemblers control the latter two. By contrast, in the US car industry most components are produced internally and the rest are procured by open bidding.

Japanese organizations possess a good interface environment between departments as they are used to perform simultaneous engineering whereas American organizations have a poor interface between development, production and sales department. Since Japanese focus is on quality, therefore the cost is higher whereas American organizations bear cost at an economic quality level.

The difference between the Japanese and American managerial economy is simple. Japan – followed by inefficiency produces results from market imperfections, while on America not being quite a perfect market, runs a labour market that functions reasonably well. An American employee will offer his talents to the highest bidder. Japanese salary differentials are compressed compared with other societies. The eighty-odd headhunting firms in Tokyo do nearly all their business enticing Japanese working for one American firm to go and work for another, occasionally topping up the supply of sellers in their market by recruiting a few dropouts or adventurous dissidents from major Japanese firms (Aoki & Dore, 1996, p. 380).

Work Cited

Aoki Masahiko & Dore Ronald, (1996) The Japanese Firm: The Sources of Competitive Strength: Oxford University Press: Oxford.

Kudo Akira, Kipping Matthias & Schroter G, Harm, (2003) German and Japanese Business in the Boom Years: Transforming American Management and Technology Models: Routledge: New York.

Kono Toyohiro, (2001) Trends in Japanese Management: Continuing Strengths, Current Problems, and Changing Priorities: Palgrave: New York.

Murphy, R. T. (2000) ‘Japan’s Economic Crisis’, New Left Review, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 25–53.

Y. Fukada and R. Dore, (1993) Nihongata shihonshugi nakushite nanno nihon ka (What Japan without Japanese Style of Capitalism?), Tokyo: Kobunsha..