There are a number of ways that may be used to improve the conditions under which society lives nowadays, and one of these ways is a proper development of intelligence-led policing. Among the variety of peculiarities of this business model, it is necessary to underline the idea that it deals with crime intelligence and all those data analyses that aim at facilitating and reduction of crimes. The concept of this intelligence-led policing concept is closely connected to crimes and other types of offences that bother the vast majority of population: fighting crime plays an important role and requires a considerable amount of time and efforts. Due to such serious and significant intentions of this paradigm, it has already been developed in many countries like the United States of America, New Zealand, and Australia (Wakefield, 2009). Many sophisticated writers, scientists, and thinkers define intelligence-led policing as a philosophical issue or as a complex mechanism that has to be properly organized (Wakefield, 2009; Kemshall, 2003). To realize the utility of intelligence-led policing in such countries like Australia, it is very important to define its meaning clearly, functions accordingly, and effects observed. The evaluation of Australian state of affairs and its comparison to the event in other countries like September 11, 2001 in US helps to clear up whether the offered model of intelligence-led policing is really effective and working in regard to the challenges people have to face day by day. In this paper, the utility of intelligence-led policing will be criticised to define its distinctive features in comparison to other business models, its roots and possible ways of development, the level of crime reduction, and some other effects on the Australian style of life and improvements of living conditions.

The achievements demonstrated by Jerry Ratcliffe help to comprehend the essence of intelligence-led policing and to clear up how the chosen model may be implemented to Australia and help its citizen fight against crimes. He admits that this term has been used as an integral part of Australian modern policing in the 1990s and is known now as an intelligence-driven policing concept (Ratcliffe, 2003). In fact, there are several perspectives to rely on while defining the essence of intelligence-led policing, and each of these ideas has its powerful sides and slight shortages. It is defined as a model for risk management. Such definition exposes the idea of its correctness in comparison to the other existed models. However, Australia is known by the ability to develop exiting models such as Military Bureaucratic Model or Community (Oriented) Policing Model (Cools & Easton, 2009), this is why it is necessary to narrow down such definition and think over some other aspects of the term under consideration. Ronczkowski (2006) explains intelligence-led policing as “the collection and analysis of information to produce an intelligence end product designed to inform law enforcement decision making at both the tactical and strategic levels” (p. i). However, if this model is pure strategic, it can hardly differ from other models which exist in Australia and help to protect society against crimes and other threats. This type of policing is also regarded as a philosophical approach to the problems that helps to identify crime causes, motives, and different problems that may associate with it. Considering all these approaches and ideas, functions and effects, Radcliffe (in press) makes a powerful attempt to present a clear and what is more obligatory informative definition of intelligence-led policing as:

“a business model and managerial philosophy where data analysis and crime intelligence are pivotal to an objective, decision‐making framework that facilitates crime and problem reduction, disruption and prevention through both strategic management and effective enforcement strategies that target prolific and serious offenders” (p. 3)

The utility of intelligence-led policing may be identified and analyzed by means of evaluation of this policing origins and the process of development. Though Australia is far from such continents as North America and Europe, the events that happed in different countries have certain effects on the Australian government and measures that need to be taken. Australian police commissioners were the first legally defined bodies that supported the idea of intelligence-led policing. Criminal activities are usually targeted, and the representatives of the police became able to recognize all those targets so that they became able to find out all the necessary peculiarities, measures of prevention, and forecasting of possible crimes. The adoption of this model should promote improved and up-to-date accountability structures by means of which investigations of crimes became easier and more organized. In spite of the fact that the process of implementation within police service usually causes a number of unpredictable costs and challenges, this intelligence-led policing model is supported by the desire to explicit crime reduction and, what is more important, crime prevention. Events that happened September 11, 2010 and some other terroristic attacks in Europe made the Australian government think over the quickest ways of this paradigm’s implementation. The possibility to be attacked without any warnings and evident reasons terrifies many countries, and the idea to develop new strategies that are unknown to public is a good way to strengthen security. Ratcliffe (in press) admits that there was some kind of pressure for specific managerial improvements due to the considerable growth of organized crimes and impossibilities to prevent or at least decrease the level of losses and outcomes inherent to these crimes. The utility of the existing intelligence-led policing may be justified due to such drivers as “demand gap, improvements in information technology, new public managerialism, and the growth of organized crime” (Ratcliffe, in press, p.3) and the possibility to reduce the number of crimes by means of this model.

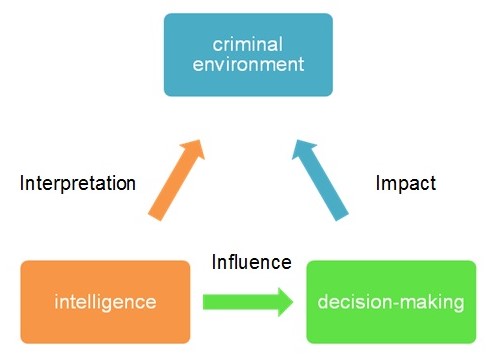

From a pure criminal perspective, the main features of intelligence-led policing include such activities as the creation of special federal guidelines aim at controlling police conduct, identification of security threats that usually come from terrorists and gangs, and improvements of police computing systems. It is not enough to find out a solution to one particular problem and clear everything up. The idea of intelligence-led policing lies in the fact that people should take care of long-lasting solutions and offers to be able to predict future crimes and offenders. Decision making process is crucial for the chosen paradigm, however it does not work separately without the following concepts to be considered: intelligence as a value-added product (Radcliffe 2003), the criminal environment with its proper interpretation, and strategic targeting with the help of which it is possible to prioritize the groups for the earliest interventions (Gonzales, Schofield, & Herraiz, 2005). The idea to implement intelligence-led policing turns out to be a very serious aspect to deal with because it has a number of peculiarities which mix up with the peculiarities of the National Intelligence Model. The latter model provides a powerful framework by means of which intelligence-led policing is conducted (Carter, 2004; Wakefield, 2009).

The evaluation of effectiveness of intelligence-led policing shows that implementation of this concept has a number of positive and negative outcomes. On one hand, the reduction of crimes is evident. Variety of strategic management approaches and different enforcement strategies are considered to be the main outcomes for consideration. Ratcliffe (in press) presents an example that is taken from the Australian reports where burglaries in Canberra were considerably reduced by “focusing patrol activity in burglary hotspots and through the intelligence-led targeting of repeat offenders” (p.9). The results are rather impressive: more than 50 burglaries are prevented every week. The idea that crimes are prevented, offenders are under the control of police officers, and citizens are in safe sounds rather persuasive and people truly believe that the chosen concept proves that improvements, new technologies, and demands have to be considered all the time. And one of the most powerful evidences is connected to the fact that attacks similar to those of September 11, 2001: Australian government is ready to take all necessary measures to protect its citizens.

Threats of intelligence-led policing lie in the fact that constant improvements and possibilities of implementation other strategies are also possible. Ratcliffe (2003) signifies that “intelligence-led policing strives for greater efficiency in policing, but it has also been accompanied by other efficiency methods, some of which conflict with intelligence-led policing” (p. 5). Another weak side of the chosen paradigm is cooperation of components on the necessary level: if influence and interpretation are considered without impact, intelligence-led policing will never occur. In spite of the fact that this policing helps to prevent crimes, the obligations which are inherent to its developers increase day by day, and people are not always ready to interpret the situation on the necessary level. This is why implementation of this model requires particular conditions, components, and functions to be performed. In other words, one single mistake may lead to unpredictable results and wrong work of the whole system. Is it possible to believe that reduction of crimes is always possible under the chosen system? In fact, it is impossible to get positive answer to such rhetorical question.

Intelligence-led policing may be improved in many different ways, and each country has to take specific steps in accordance with the conditions they live under and criminal activities spread over the country. In other words, the chosen paradigms has to be improved centrally (touching upon its peculiarities and functions) and locally (considering the conditions of the community). Many law enforcement areas are involved into this improving process, and the analysis of location, time, models of vehicles, and property types should be carried out. This is why it is important to pay more attention to the evaluation of the already known data, criminal environment, and nature of criminals who are involved into this process.

In general, the idea of intelligence-led policing implementation has a number of benefits. However, as any other program, model, and paradigm, this policing introduces several challenges to cope with. The chosen practice may take many different forms, and each form requires a certain approach and identification of variables that contain information about the criminal environment, intelligence, and decision-making process. Due to widespread fixation of outcomes, police becomes unable to rush cops from hotspots. This is why it is very important to remember the aims of the chosen paradigm are not only proper intelligence but also proper policing, evaluation, and prevention of crimes. If reports show that crimes are reduced, the effectiveness of such intelligence-led policing is evident and needs to be improved periodically not to lose effective tactics and approaches.

Reference List

Carter, D.L. (2004). Intelligence-Led Policing: The Integration of Community Policing and Law. From Law Enforcement Intelligence: A Guide for State, Local, and Tribal Law Enforcement Agencies. Washington: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services.

Cools, M & Easton, M. (2009). Readings on Criminal Justice, Criminal Law & Policing. Portland: Maklu.

Gonzales, A.R., Schofield, R.B., Herraiz, D.S. (2005). Intelligence-Led Policing: The New Intelligence Architecture. Bureau of Justice Assistance.

Kemshall, H. (2003). Understanding Risk in Criminal Justice. Philadelphia: McGraw-Hill International.

Ratcliffe, J. H. (2003). Intelligence-led Policing. Australian Institute of Criminology, 248.

Ratcliffe, J.H. (in press). Intelligence-led Policing. In Wortley, R, Mazerolle, L, & Rombouts, S (Eds) Environmental Criminology and Crime Analysis. Cullompton, Devon: Willan Publishing.

Ratcliffe, J.H. (in press). Intelligence-led Policing: Anticipating Risk and Influencing Action. IALEIA Publications.

Ronczkowski, M. (2006). Terrorism and Organized Hate Crime: Intelligence Gathering, Analysis, and Investigations. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Wakefield, A. (2009). The SAGE Dictionary of Policing. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.