Introduction

Art is present in nature, just as nature is present in art. The very term “Nature” is very broad and all-encompassing, like life itself. It is connected to humanity at a deep, intimate level. We emerged from it, and we would likely return to it, eventually. From ancient artists to modern creators, many drew inspirations from many aspects of nature, ranging from the harmonious coexistence of various flowers, trees, and plants to the ferocious and macabre cycles of life and death that often go unseen to the human eye.

Every artist sees something in nature that appeals and calls to them. In the age of modern arts, when both the creators and the audience is less concerned with the physical form and more with the underlying messages and feelings that art invokes, the multi-faceted topic of nature emerges once more in all of its beautiful and frightening glory.

This paper is dedicated to the visual art analysis of the two prominent artists of the modern age – Lars von Trier and Fiona Hall. They are quite unlike one another – one is a cinema director and screenwriter while the other is an artistic photographer and sculptor.

What unites them are the unusual and elaborate portrayals of nature in their works. Unlike the photorealistic pictures of the classic artists of old, that had no deeper meaning behind it other than trying to replicate the splendor of the forests and wildlife to the best of their ability, the depictions of nature in modern art go beyond that. They tell a story, and they are meant to invoke feelings and thoughts.

Lars von Trier depicts nature as a silent character, addresses the connection between nature and humans in three of his films named Dogville, Antichrist, and Melancholia. Fiona Hall, on the other hand, looks at nature through the prism of history, colonization, and consumerism. This is illustrated by three of her famous works named Leaf Litter, Cash Crop, and Dead in the Water.

Definitions of Nature in Art

According to Raymond Williams, “nature is a contested term that means different things to different people in different places.” While there are many possible interpretations of the word, they typically fall into one of three categories:

- Nature as the essence of something.

- Nature as a material place, like a forest or a garden.

- Nature as a universal order or force, which could include humans, oppose them, or both.

Darvin described nature not as a passive entity, but as a living and breathing organism, a force of alteration, innovation, and evolution. He classifies it as a medium within which humans exist, but which does privilege the human.

Viewing nature in the context of the Anthropocene era is a somewhat modern notion, which sprouted into existence during the second half of the 20th century. After the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, humanity was officially acknowledged by the scientific community as the driving force behind geological and biological change. The artists reflected on that by portraying nature through a prism of industrialization, globalization, and politics.

Lars von Trier– general themes and attitudes towards Nature

Lars von Trier’s view of nature can be seen throughout his unfinished trilogy, namely Dogville, Antichrist, and Melancholia. He portrays Nature as a terrifying entity, yet mostly concerned with itself – it is neither benevolent nor malevolent. In that, it relates to the Darwinian view of nature. It is not a faceless force, though it is portrayed that way in the first film, Dogville.

Nature has an identity and gender in his works. It embodies everything that a man is not and stands in opposition to his logical, oppressive, and destructive nature. The main characters of all three films are women, and their relationship with Nature is what ultimately defines whether they succumb to the man-driven society or liberate themselves through the acceptance of their nature.

In Dogville, the central character is a woman who moved to a small mining town to escape the big city. The town ultimately becomes her prison, as the predominantly male populace forces her into submission. The looks of the landscape in this film are mostly metaphoric and sketchy, as the female heroine rejects the possibilities that Nature offers, instead choosing to seek comfort in people. Through the rejection of Nature, she rejects herself and becomes one with the opposite, destructive side.

In Antichrist, Nature is revealed as a ghastly entity. Nature is neither benevolent nor evil, and it reflects the attitude of the female character towards it. She is afraid of the woods, and they appear macabre to her – painted in cold blue hues, covered with fog. Only when she feels the call of nature and maternity, does the color change from blue to a warmer green.

The landscape and the forest begin communicating with the female as the scene grows dark. The woman’s husband deals with Nature the same way he deals with his wife – without understanding it. In the end, while the woman accepts nature and relinquishes her fear, she returns to the human society, and dead bodies of mourners rise from the fog as if to wish her farewell. The scenes in this movie reveal the femininity of Nature both figuratively and conceptually, in opposition to the logical and inflexible mind of the Man.

In Melancholia, one of the female characters also hears the call of Nature, but unlike in the other two films, she does not push Her away, instead of agreeing with the message and becoming in tune with it. This paves her way to personal liberation from male domination. Nature is portrayed differently in Melancholia, in comparison to Antichrist – it is groomed and shows signs of human order and tampering, which saps the life away from it.

Despite being seemingly under control, Nature remains a separate entity, and forms a bond with Justine, in contrast to the orderly and conventional Claire. As the prospect of imminent death from the clash between planets looms over them, both sisters join each other in accepting Nature, and blend into the landscape, finding harmony with the surroundings.

As we could see, the female characters find true peace only when they hear and accept the Nature’s call, the call of their femininity, rather than conforming to the standards of the orderly and foreign male society. Yet it is not the purpose of Nature to make them accept it – she simply offers a hand, and it is up to the characters to take it.

Nature in Fiona Hall’s Art

Fiona Hall portrays nature through a prism of modern human expansion and colonization. Her works represent a blend of modern materials such as plastic or soap and portrayals of animals and plants. Frequently, the objects of her art are showcased in museum-like stands. However, these stands are also part of the composition, representing the human’s need to study and classify nature, after having reaped it. These tendencies could be found in three of her compositions, called Leaf Litter, Cash Crop, and Dead in the Water.

Leaf Litter is a series of paintings made in gouache. Each painting consists of a highly photographic drawing of various botanical cultures over the currencies of different nations. These illustrations make the viewer think about the correlation between money and nature, as many of our economies are dependent on exploiting nature to survive. In Leaf Litter, nature is looked upon as a resource in many ways. It is dead, dried up, and used not only to earn money but also to produce it, as the paper for the bills also comes from natural sources.

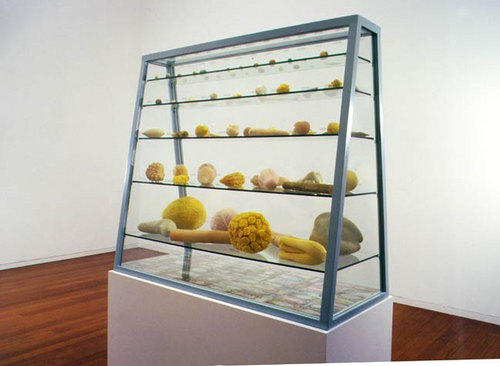

Cash Crop continues the idea of utilitarianism of humanity towards nature. It represents a botanical stand, where various crops are displayed and classified according to their names and purpose. When looking at the stand full of dead crops made out of soap, one tends to wonder whether human cultivation and desire for knowledge help us understand nature, or kills it. The composition invokes uneasy feelings since the viewers are more used to depictions of living nature. In Cash Crop, nature is dead, dissected, and classified.

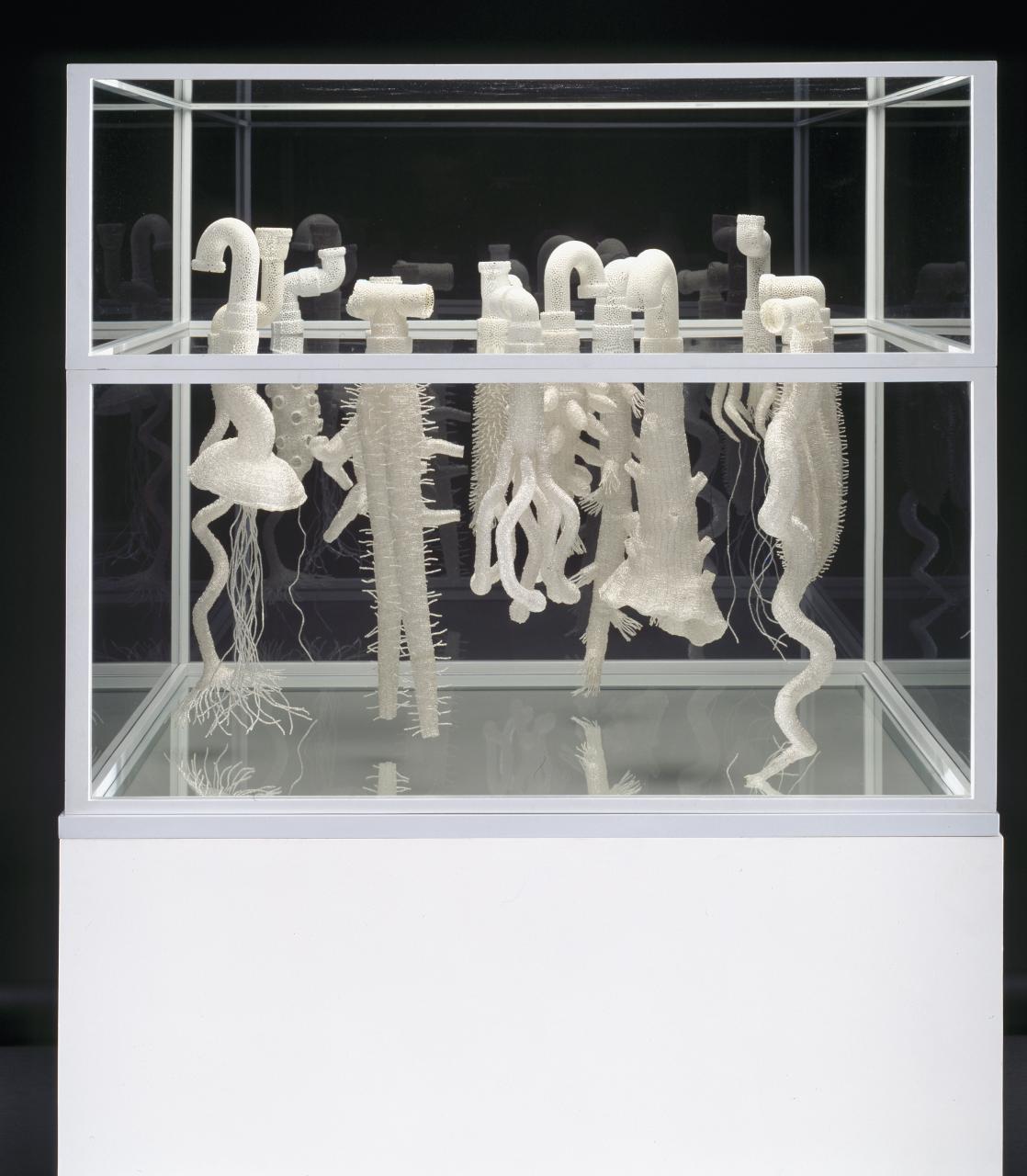

Dead in the Water shares this line of thought, though it takes a different turn in regards to the portrayal of nature. While nature is dead in previous works, in here, it is alive. The material used for the creation of the display is PVC, which is artificial. Yet, through skillful manipulation, it is made to look alive, almost ethereal, as the pipes turn into roots of numerous plants. The stand plays a role similar to that in Cash Crop. However, the composition itself represents a struggle between humanity and nature, good versus evil, and old versus new. The fact the plants are growing out of PVC pipes shows that nature always finds a way.

In all of her works, Fiona Hall sends a strong message to the viewers. The the message is not obvious, as it requires those who look upon her art to think and analyze the pieces and the thoughts behind them. However, the feelings of that something is wrong invoked throughout the three compositions reviewed in this paper, certainly indicate that the artist does not approve of how humanity treats nature. Thus, her art contains a strong political and environmental message.

Conclusions

Fiona Hall and Lars von Trier have different views on nature and how it is portrayed. In Trier’s films, Nature is a living entity, mysterious and vibrant. In Hall’s sculptures, it is depicted as a dead and dried-up shell of its past self. However, there are similarities between them as well.

For both of them, Nature is feminine and in opposition to the logical and oppressive male order. Their art invokes contemplation and thought, as the images, they present to the audience are complex in many different ways. The environmental message is stronger in Hall’s works, while Lars von Trier’s films are more dedicated to the struggles of the feminine in a masculine society.

Bibliography

Antichrist. Digital Image. Filmlinc. Web.

Arias-Maldonado, Manuel. Environment and Society: Socionatural Relations in the Anthropocene. New York: Springer, 2015.

“Cash Crop.” Art Gallery NSW. Web.

“Works by Fiona Hall.” Art Gallery NSW. Web.

“Nature, a Character in Lars von Trier’s Works.” Cinema Scandinavia. Web.

Dogville. Digital Image. Alchetron. Web.

Ginn, Franklin, and David Demeritt. Nature: A Contested Concept. London: Sage, 2009.

Grosz, Elizabeth. Becoming Undone: Darwinian Reflections on Life, Politics and Art. London: Duke University Press, 2011.

Hall, Fiona. 1999. Cash Crop. Sculpture. Sydney: Roslin Oxley Gallery.

Hall, Fiona. 1999. Dead in the Water. Sculpture. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria.

Hall, Fiona. 2000. Leaf Litter. Sculpture. Canberra: National Gallery of Australia.

“Fiona Hall: Sydney Ambush.” Mahon Studio. Web.

Melancholia. Digital Image. The Wit Continuum. Web.

“Leaf Litter.” National Gallery of Australia. Web.

Nicole Kidman. “Other Films by Lars von Trier.” Nicole Kidman. Web.

“Case Study One – Nature.” Year 11 Visual Arts. Web.

Zolkos, Magdalena. “Violent Affects: Nature and the Feminine in Lars Von Trier’s Antichrist.” Parrhesia 13 (2011): 177-89.