Performing an ultrasound of the gall bladder only

Patient preparation

The examiner introduces himself to the patient. The relevant clinical information regarding the patient should be confirmed. The examination area should be checked (Bisset, 2002). The examiner explains to the patient how the procedure will be performed and how much time is necessary to finish the examination. Verbal consent is obtained from the patient. The patient should be dressed appropriately for the procedure and feel entirely comfortable (Ultrasound of the gallbladder 2012).

A brief medical history is taken, and the following details are obtained: if the pain is present, its location and duration are verified; the presence of any nausea or vomiting should be noted; any history of the abdominal disease or abdominal surgery is discussed; any current medications are discussed; any recent tests or imaging procedures are clarified with the patient (Block 2004; Ultrasound of the gallbladder 2012).

It should be ensured that the patient is nil per os (NPO) before the procedure. The patient has explained the technique of breathing during the ultrasound scanning. The patient is asked to lie face up on the examination bed. The patient should feel comfortable, and if necessary, his or her position should be adjusted with the help of pillows or foam wedges (Ultrasound of the gallbladder 2012).

Equipment

The ultrasound machine, gel warmers, power beds should be prepared in advance to start the examination. The work of the computer system, sonographer’s worksheet, and the printer should be checked. The bed should be prepared (linen, cloths, towels).

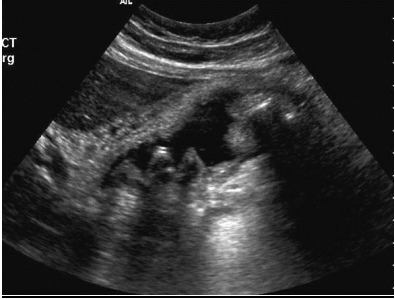

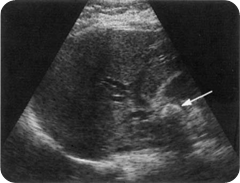

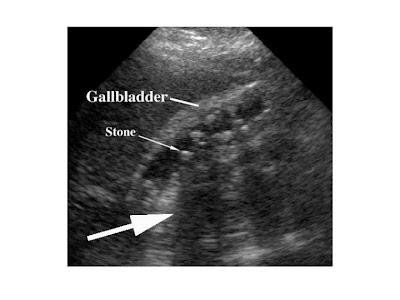

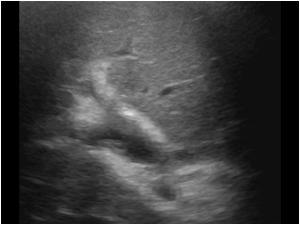

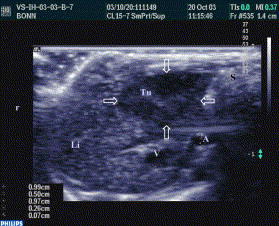

The next stage is to select the transducer’s frequency and perform the survey. It is essential to choose the right subcostal or the right intercostal positions for the survey. While surveying the gallbladder area, it is necessary to identify the anatomical landmarks. The healthy gallbladder is oval and echo-free. It is located on the inferior part of the liver. It is required to refer to the sonographic landmark of the gallbladder. Scanning the gallbladder, the examination of the neck, fundus, and the gallbladder wall is realized. It is possible to scan transversely through the gallbladder, covering the fundus to the neck. Finally, the thickness of the gallbladder wall should be measured. The presence of any gallstones can be noted.

The image shows definite gall bladder disease. A positive Murphy sign is usually the indicator of acute cholecystitis. Ultrasound imaging helps investigate the gall bladder disease sensitively. It is possible to observe the changes in the gall bladder, which are characteristic for the acute cholecystitis. It is typical for the gall bladder, which is consistent with gallstones to have the acoustic shadow, which can be easily observed with the help of ultrasound. Gall stones observed in the gall bladder of the patient affect the significant inflammation of the gall bladder’s mass. Gall stones are specific disorders in the gastrointestinal tract, which cause the pain and change the function of the gall bladder. Thus, referring to the image, it is possible to observe the distended gall bladder, multiple gall stones, the significant thickening of the gall bladder wall, which is rather oedematous. The pericholecystic fluid can also be observed. These signs in connection with a positive Murphy sign are the indicators of the acute cholecystitis.

Real-time’ techniques used to assist with the diagnosis

Computed Tomography (CT) can be used along with ultrasound since CT can detect other pathologies in the abdomen if they are present. In the case of acalculous acute cholecystitis (AAC), the use of hepatobiliary scintigraphy is debatable, and it may be used with a high clinical suspicion when the usage of ultrasound is more appropriate. Although this technique has a high sensitivity in diagnosing AAC, it cannot provide the necessary specificity. This problem can be avoided with using of morphine-augmented scintigraphy.

Nevertheless, CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is considered as useful adjuncts to ultrasound because of providing accurate real-time images and results (Yusoff, Barkun & Barkun 2003). Ultrasound is more effective than the mentioned techniques for the initial diagnosing of cholecystitis. CT and MRI can be used as additional methods.

Patients with the above pathology often clinically present with jaundice

Jaundice

When the level of bilirubin in the blood is abnormally high, then people’s sclera and skin become rather yellow. This process and condition are known as jaundice. Clinically, jaundice becomes obvious when the serum bilirubin level becomes more than 2.5mg/dL (Smeltzer et al. 2010).

‘Indirect’ and ‘direct’ bilirubin, and their functions in detecting liver diseases

Bilirubin is present in red blood cells. It can be harmful because it is a breakdown product. The terms ‘indirect’ and ‘direct’ bilirubin describe the way according to which bilirubin can react to testing dyes being conjugated or direct and unconjugated or indirect. Direct bilirubin reacts to the reagents when they are added directly to the blood. To make the unconjugated bilirubin react, it is necessary to add some alcohol. Thus, indirect bilirubin cannot react independently (Stocksley, 2001).

Patients who have Mirizzi syndrome may also present with jaundice as well as having a gall bladder

Mirizzi Syndrome

Mirizzi syndrome is the hepatic duct obstruction. The obstruction is usually by calculus, and it is impacted in Hartmann’s pouch (Yusoff, Barkun & Barkun 2003). This condition often leads to significant complications because surgery is necessary to diagnose and treat the syndrome. There are four types of the syndrome (Yusoff, Barkun & Barkun 2003).

Mirizzi syndrome is a potential cause for acute cholangitis

Acute cholangitis

Acute cholangitis can be defined as a systemic infectious disease. The symptoms are caused by acute inflammation and infection in the bile ducts. It is possible to observe the combination of biliary obstruction and bacterial growth (Mosler, 2011).

Differences between acute cholangitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis

Acute cholangitis differs from sclerosing cholangitis significantly. Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) can be defined as chronic cholestatic liver disease. It is typical for intra and extrahepatic bile ducts (Worthington & Chapman 2006).

Comparison of the possible sonographic appearances between these two pathologies

(Smeltzer et al. 2010).

Patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis are at increased risk of developing cholangiocarcinoma

The classification of cholangiocarcinomas

It is possible to determine four types based on their anatomical location. Cholangiocarcinomas may be classified as intra and extrahepatic. Moreover, it is possible to determine the extrahepatic type (Blechacz, 2008). The first type is based on the involvement of the common hepatic duct distal to the biliary confluence; the second type is the involvement of the biliary confluence; the next two types are the involvement of the biliary confluence along with the right hepatic duct and involvement of the biliary confluence along with the left hepatic duct; and the last type is the involvement of the confluence with the right and left hepatic ducts (Blechacz & Gores, 2008).

Further subclassification is based on their macroscopic appearance. Extrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas are classified as sclerosing, nodular, and papillary. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas are classified as periductal infiltrating, mass forming, intraductal, and mass forming and periductal infiltrating (Blechacz et al. 2011).

The aetiology of cholangiocarcinoma

It is possible to concentrate on such risk factors as primary sclerosing cholangitis and hepatobiliary flukes (Opisthorchis viverrini and Clonorchissinensis) which can be ingested from the undercooked fish and hepatolithiasis. Other risk factors associated with the aetiology of cholangiocarcinoma include biliary malformations (Caroli’s disease), Hepatitis C, cirrhosis, biliary enteric drainage procedures in the presence of recurrent cholangitis, substances like thorotrast and dioxins (Blechacz & Gores, 2008).

The prognosis of cholangiocarcinoma

The prognosis of cholangiocarcinoma is often poor. Surgery is the only curative therapy. Nevertheless, the aetiology and molecular pathogenesis of cholangiocarcinoma are better understood now than in the past. Also, with improvement in diagnostic abilities, it is possible to diagnose patients at the earlier stages, and therefore, it is possible to cure the disease. A 5-year survival rate can be obtained with liver transplantation plus neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in highly selective patients with unresectable perihilar cholangiocarcinomas (Blechacz & Gores, 2008).

The possible differential diagnoses for cholangiocarcinomas

The possible differential diagnoses for cholangiocarcinomas are hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), ampullary carcinoma, pancreatic carcinoma, choledocholithiasis and cholangitis.

Patients with cholangiocarcinomas may present with altered blood tests

Cholangiocarcinomas are the transformations in bile ducts that is why blood tests, as well as liver function tests of the patients with cholangiocarcinomas, often represent the elevated levels of bilirubin. The levels of alkaline phosphatase and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase are also often increased. Thus, blood tests are altered, and they represent high levels of cholestasis. It is also possible to use the CA19-9 marker as the test for cancer antigens to confirm the diagnosis because it is usually elevated. However, it is essential to pay attention to the non-specific markers of malignancy which can be altered. They are the reduced levels of albumin and haemoglobin which should be tested with other techniques to confirm the results (Lau & Lau 2012).

Patients with choledochal cysts may present with recurrent acute cholangitis and are also at increased risk of developing cholangiocarcinomas

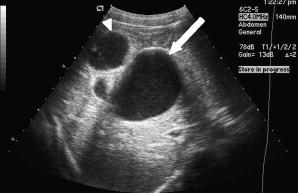

Choledochal cyst

Choledochal cysts are congenital bile duct anomalies which appear as cystic dilatations of the biliary tree. They depend on the specific extrahepatic or intrahepatic biliary radicles. Choledochal cysts are classified into five major types. Type I and IV are subclassified into types IA, IB, IC, IVA and IVB (Keir 2007).

The aetiology of choledochal cysts

The aetiology of choledochal cysts is not very clear. Babbitt’s theory of cysts has gained a lot of popularity. According to this theory, the abnormal pancreaticobiliary duct junction (APBDJ) matters. The mix of the pancreatic and biliary juices can activate the pancreatic enzymes which cause inflammation of the biliary duct wall. This process leads to dilation (Singham et al., 2009).

There is also an opinion that adult cysts with distal obstruction can lead to fusiform lesions (Bluth 2001). Choledochal cysts can be associated with colonic atresia, duodenal atresia, imperforate anus, pancreatic arteriovenous malformation, and multiseptate gallbladder (Singham et al. 2009).

References

Bisset, K 2002, Differential diagnosis in abdominal ultrasound, Elsevier, India.

Blechacz, B 2008, ‘Cholangiocarcinoma’, Clininc Liverer Diseases, vol. 12 no. 4, pp. 131-150.

Blechacz, B & Gores, G 2008, ‘Cholangiocarcinoma: advances in pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment’, Hepatology, vol. 48 no. 1, pp. 308–321.

Blechacz, B, Komuta, M, Roskams, T, & Gores G 2011, ‘Clinical diagnosis and staging of cholangiocarcinom’, Gastroenterology & Hepatology, vol. 2 no. 8, pp. 512-522.

Bluth, E 2001, Ultrasound: a practical approach to clinical problems, Thieme, USA.

Block, B 2004, The practice of ultrasound, Thieme, USA.

Keir, L 2007, Medical assisting, Cengage Learning, USA.

Lau S & Lau W 2012, ‘Current therapy of hilar cholangiocarcinoma’, Hepatobiliary Pancreatic Diseases International, vol. 11 no. 1, pp. 12-7.

Mosler, P 2011, ‘Management of Acute Cholangitis’, Gastroenterology, vol. 7 no. 2, pp. 121–123.

Singham, J, Yoshida, E, & Scudamore, C 2009, ‘Choledochal cysts’, Journal of Surgery, vol. 52 no. 5, pp. 12-18.

Smeltzer, S, Bare, B, Hinkle, J, & Cheever, K 2010, Brunner and Suddarth’s textbook of medical-surgical nursing, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, USA.

Stocksley, M 2001, Abdominal ultrasound, Cambridge University Press, USA.

Ultrasound of the gallbladder. 2012. Web.

Worthington, J & Chapman, R 2006, ‘Primary sclerosing cholangitis’, Journal of Rare Diseases, vol. 1 no. 4, pp. 22-29.

Yusoff, I, Barkun, J, & Barkun, A 2003, ‘Diagnosis and management of cholecystitis and cholangitis’, Gastroenterology, vol. 10 no. 12, pp. 1145–1168.