Background

Beer is one of the world’s most beloved alcoholic beverages with a rich history and century-old traditions. Beer production involves brewing cereal grains with the most popular choice being malted barley and other options including wheat, maize (corn), and rarely, rice.

Since the industrial revolution, the brewing industry has turned from domestic manufactures into a global business that includes multinational giants as well as regional and local producers. Typically, beer is packed in bottles and cans; however, in bars and pubs, it is no rarity to see it available on draught. The modern beer is characterized by the strength within the 3.5% to 6% alcohol by volume (ABV) range.

However, due to the impressive diversity of beer culture and brewing methods, ABV may vary greatly starting as little as 0.5% and amounting all the way up to 20% (DeSalle and Tattersall 5). Some breweries embarked on creating beer as strong as spirits, and the most outstanding attempts resulted in beverages with an ABV of 40%.

Brief History

The written history of many ancient civilizations includes frequent mentions of beer, be it brewing methods, religious references, or laws aimed at controlling consumption and distribution. The archaeological evidence revealed that humankind commenced brewing beer as early as 11,000 BC (DeSalle and Tattersall 15). Some scientists go as far as making assumptions that beer used to play a significant role in the formation of civilizations and was highly appraised for not only its inebriating properties but also nutritional value (DeSalle and Tattersall 17).

For instance, workers at the construction site of the Great Pyramids in Giza, Ancient Egypt, received the daily norm of four to five liters of beer per person, which at the time, was seen as instrumental to the successful realization of the building plan (DeSalle and Tattersall 25). The written legacy of Mesopotamia entailed religious texts whose creation was allegedly aimed at preserving beer recipes in a nation that was predominantly illiterate.

Fast forward to modernity, in the 16th century, William IV, the Duke of Bavaria, passed what was recognized as the first European law regulating food quality, which included providing guidelines for the brewing process. The Industrial Revolution was a critical point in the history of beer as its production moved from local and artisanal to industrial. The introduction and refinement of thermometers and hygrometers allowed brewers to seize greater control over the process (DeSalle and Tattersall 67). By the 21st century, the brewing industry had grown exponentially, making it the third world’s most popular drink after water and tea.

Current Consumption and Production: In the World and Canada

In Canada, beer made its first appearance in the 17th century when it was brought by European settlers and colonists. The first commercial brewery was established in 1650, and soon, the beer business started to thrive and prosper due to the vast popularity of the beverage. Moreover, the cold climate facilitated the production in the absence of refrigerators. The industry took a nosedive between 1918 and 1920 due to the federal prohibition but resumed quickly after the law was repealed (DeSalle and Tattersall 105).

As of 2015, beer is recognized as the most popular drink in Canada. 57% of Canadians consume beer regularly with the demographic groups of adults aged 18-34 (39.1%) and 34-49 (30.2%) being the core customer base (“Estimated Domestic Beer Consumption”). Even though sales plummeted in 2007, in recent years, they have been on the rise again with the average sales value of $304.7 a year per capita (“Estimated Domestic Beer Consumption”).

As for the world statistics, 1.95 billion liters of beer is produced annually with China being both the largest producer and consumer of the beverage (“Global Beer Industry”). It is projected that the popularity of beer will continue to be on the rise with the industry now tapping into emerging alcohol markets in Asia-Pacific.

Product and Processing

Brewing Stages

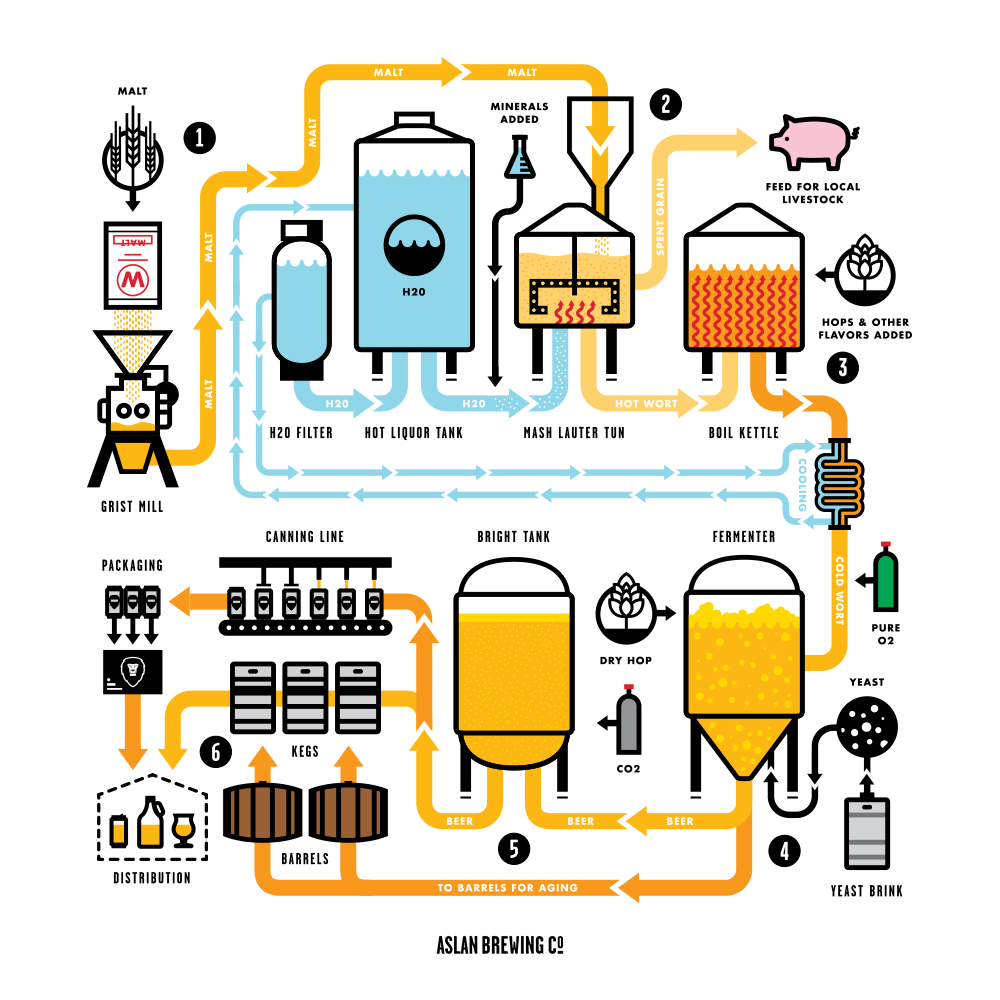

Brewing is a complex process that involves several different stages (see fig. 1). Below is a detailed description of each phase:

Malting

The malting process is aimed at converting raw cereal grains into malt. First, it is necessary to ensure that barley or any other grain is in its best condition, and namely, check grain moisture (13%), nitrogen contents, and the absence of fungus. Grains are dried by circulating air at a temperature of 50°C.

Further, dry cereals are cleaned by removing foreign matter with the use of de-stoners, shaking screens, and magnets for metallic solids (Bamforth 42). The active malting process begins with steeping when by adding water, grain moisture increases from 13% up to 40-45% (Bamforth 42). Lastly, germination facilitates the development of malt enzymes which break down the starch.

Kilning

Kilning does the opposite of malting: it reduces the grain moisture radically during the free drying stage when the temperatures are cool and the forced drying stage characterized by exposure to 80°C heat (Bamforth 60). The final stage of kilning is the cooling of the malt.

Mailing

The dried grains are put between rollers where they are crushed down to a coarse powder, grist.

Mashing

At this stage, brewers mix grist with water, and the materials are maintained at a temperature of 65°C for an hour. During the mashing process, the released amylase enzyme hydrolyzes the starch in the grist, and as a result, single sugars, maltose, dextrose, and others are produced. Similar to sugar production, the protein undergoes hydrolysis by proteolytic enzymes and breaks down to small fragments and amino acids.

PH and temperature moderate the degree of enzymatic hydrolysis: the optimal temperature for β-amylase is 57-65°C whereas α-amylase is the most active at 70-75°C (Balmforth 119). The end goal of mashing is obtaining the liquid called wort. At the final stage, brewers filter the resulting materials to remove such residues as husks and precipitated proteins.

Boiling of Wort

Further, brewers boil the filtrate for two to three hours while stirring the material continuously. At various points in time during the boiling stage, it is appropriate to add hop flowers. The activities at the present stage serve several goals at once. First, boiling helps to extract flavor from hop flowers, coagulates the remnants of protein, and hydrolyzes them, which helps with the removal.

The enzymes that were instrumental during mashing are no longer needed at this stage, and during boiling, they are inactivated. If these measures are not taken promptly, the sugar caramelizes and spoils the product. By boiling wort, brewers ensure its sterilization and gain more control over its concentration.

It is important to emphasize the importance of adding hops as they constitute one of the four essential ingredients of beer in the modern brewery. The scientific name of the hop plant is Humulus lupulus; a barrel of beer requires approximately one-quarter pound of the dried female flower. Hop addition provides the end product with its pungent, aromatic properties whereas the contents of α-resin and β-resin account for the typical bitter flavor as well as a preservation against gram-positive bacteria (Balmforth 181). Hop flower contains tannin which ensures coagulation of remaining protein. Lastly, beer owes its foam characteristic to hop flower among its ingredients.

Fermentation

The brewing industry utilizes strains of Saccharomyces and S. varum, and S. cerevisiae with the first two being top yeast and the latter being bottom yeast. The temperature apt for fermentation is usually 3-4 °C; however, in some cases, it may vary from within the 3 to 14°C range. During a 14-day process, yeast turns sugar primarily into ethanol and CO2 with the addition of a small amount of glycerol and acetic acid (Balmforth 307).

Open tank fermenters are permitted but not preferred, for a closed tank does not allow the liberation of CO2 which can be collected and used later during the carbonation stage. So-called CO2 evolution ends by the fifth day of fermentation, and past this point, yeast cells are no longer active.

Aging and Distribution

For the beer to age, it needs to be stored in a vat for several weeks to several months. During this time, the beer becomes clear due to protein, yeast, and resin precipitation. Storage is needed for amplifying beer’s aromatic characteristics since it takes time for foresters and other compounds to be produced. Once the beer has aged, brewers carbonate it by carbon dioxide of 0.45-0.52% (Bamforth 168). The final stage entails cooling, clarifying, and filtration after which brewers pack beer in bottles, cans, and barrels.

Product Composition

In 2018, federal officials of Canada suggested certain changes to beer labeling. Recent regulations that expanded the list of permitted ingredients were followed by the proposal to make the listing of each ingredient on a can or a bottle mandatory (Press). The officials argued that the definition of beer established thirty years ago, and namely a beverage that possesses “the aroma, taste and character commonly attributed to beer,” was no longer relevant (Press).

Instead, the food industry needed to comply with the permitted sugar and other additive content guidelines (Press). Globally, the four following ingredients are recognized as necessary in the beer composition: water, hops, yeast, and malted cereals (usually, barley). The list of additives used for beer production is quite extensive and includes sodium benzoate, flavor enhancers, sodium citrate, tartaric acid, corn syrup, urea, potassium sulfate, amyloglucosidase enzyme, antifoaming agents, and others.

Health and Safety Issues

Health Effects

Modern science came to a general consensus that brews are neither inherently beneficial or detrimental to human health. The expected results depend heavily on an individual’s drinking habits, quality of consumer products, and dosage. In 2016, a board of international experts conducted a systematic review of existing literature on health and beer consumption and concluded that moderate drinking decreased the likelihood of cardiovascular diseases (De Gaetano et al. 443). By moderate drinking, the researchers implied one drink per day for an adult woman and one-two drinks for a grown man.

The meta-analysis carried out by De Gaetano et al. revealed the protecting effect of beer against heart strokes; however, they did not find a prospective association between beer intake and the likelihood of the said condition (443). Some of the observational studies included in the report pointed out that low to moderate beer consumption reduced the risk of neurodegenerative diseases. All in all, De Gaetano et al. reasoned that unless an individual has a history of alcohol dependency or is at risk for alcohol-related cancers, there is no rationale behind discouraging such an individual from continuing light-moderate drinking.

For all the positive effects associated with controlled beer consumption, it would be irresponsible to dismiss basic safety guidelines. When discussing beer drinking and its benefits, De Gaetano et al. excluded children, adolescents, and pregnant women from the narrative (443).

Beer consumption is not recommended or prohibited altogether if an individual is at risk of developing a dependency, has cardiomyopathy, cardiac arrhythmias, depression disorders, or liver and pancreatic diseases (De Gaetano et al. 443). Lastly, it is evident that being inebriated is against professional safety guidelines, and even outside the workplace, individuals should not engage in activities requiring focus, concentration, and fine motor skills when drunk.

Food and Production Safety

In North America, safe beer production is regulated by the HACCP approach, which stands for hazard analysis and critical control points. HACCP outlines GMP – good manufacturing practices – which apply to the brewing industry as well. Among the key standards that a brewing facility needs to meet is a hygienic and clean environment, lean production, and preventive measure against pest infestation (“General Principles”). It is argued that the proper application of HACCP practices does not complicate the work processes but on the contrary, facilitates the workflow and reduces costs.

It should be noted that engaging in beer production is linked to significant health hazards. Among the primary risks that brewers face on the job is a toxic chemical and pathogen inhalation, especially if brewing activities take place in congested spaces (Beaufait).

When safety guidelines are not followed, employees might be exposed to toxic, flammable, reactive, and explosive chemicals. It is imperative that workers conduct lockout and tag-out procedures adequately to reduce the risk of burns and electrocutions (Beaufait). Lastly, another common cause of workplace injuries for brewers is human-machine collisions when employees do not drive forklifts safely (Beaufait). The latter pertains to those visiting breweries as well as they should take precautions on par with workers.

Conclusion

Beer remains at the peak of popularity among such widely consumed beverages as water and tea. The history of brews dates back to the 11th millennium BC whereas the earliest chemical and archaeological evidence of its production belong to such ancient cultures as the Sumerian civilization and Ancient Egypt. Canada inherited beer brewing traditions from Europe when settlers established the first commercial facilities on its territories in the 17th century.

As of now, beer is the most beloved alcoholic beverage among Canadians with young adults and the middle-aged being key purchasers. The brewing process typically involves seven stages and is characterized by its sophistication and scientific precision. The complexity of beer production is the rationale behind strict food safety requirements in compliance with the North American HACCP approach.

On the job, brewers should not only ensure the proper conduction of each procedure but also stay safe and avoid such common professional injuries and accidents as chemical poisoning, electrocuting, and collisions. Surprisingly, moderate beer consumption has been found beneficial for health in terms of cardiovascular and neurodegenerative disease prevention.

Works Cited

Bamforth, Charles. Brewing Materials and Processes: A Practical Approach to Beer Excellence. Academic Press, 2016.

Beaufait, Jonathan. “Brewery Safety.”Graphic Products, 2015, Web.

De Gaetano, Giovanni, et al. “Effects of Moderate Beer Consumption on Health and Disease: A Consensus Document.” Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases, vol. 26, no. 6, 2016, pp. 443-467.

DeSalle, Rob, and Ian Tattersall. A Natural History of Beer. Yale University Press, 2019.

“Estimated Domestic Beer Consumption in Canada in 2018, by Age Group.”Statista, 2018, Web.

“General Principles of Food Hygiene, Composition and Labelling.” Canadian Food Inspection Agency, 2014, Web.

“Global Beer Industry.” Statista, 2018, Web.

“The Brewing Process.” Aslan Brewing, n.d., Web.

Press, Jordan. “Canada’s Beer Standards May Soon Change, Forcing Brewers to List Every Ingredient.”The Canadian Press, 2018, Web.