Introduction

The banking sector was primarily blamed for the 2008 financial crisis. Particularly, weak leadership and poor governance have been isolated as the primary cause of the crisis. Many countries utilised the opportunity of the crisis to work on improving corporate governance and leadership to avoid similar crises in the future. In the UK, Sir David Walker was tasked with coming up with measures that would enhance accountability at the institutional level. The result of Walker’s recommendations was the UK governance code of 2010 that stipulates the expected conduct for financial institutions. The guidelines contained in this Code are binding to financial institutions in the public sector. Besides the UK, several other countries have introduced leadership and governance codes.

An example is the Netherlands where the Netherlands Banker’s Association adopted a standard banking code that took effect as from January 2010. These governance codes have transformed how financial institutions are led, especially at the board level. This paper will compare two banks Lloyd Banking Group that is based in the UK and the ABN AMRO, which is located in the Netherlands. The comparison will be focused on how the two financial institutions are being led and governed during the post-2008 financial crisis era. Because both institutions operate in the public sector, they are bound by the regulations contained in each country’s leadership and governance codes. According to O’Connell (2016), leadership and governance have since been identified as a critical area in the economy of any country. Hence, governments are not leaving to chance that the banking sector is more sensitive compared to the mainstream corporate world. Therefore, stricter rules are in place to guide banks compared to the situation in ordinary companies. As such, no country can prosper without the proper regulatory mechanisms being put in place to address issues of leadership and governance.

Overview of Financial services institutions

Lloyd Banking Group

Lloyd Banking Group (LYG) is the primary UK domiciled financial institution, which provides a wide array of services, both to corporate and personal customers. Presently, the company boasts of having the most significant private shareholder base in the UK, as well as over 30 million customers. LYG is the UK’s chief provider of banking services such as current accounts, personal loans and savings, and mortgages. Its leading brands are Lloyds Bank, the Bank of Scotland, and Halifax. Combined, these three brands operate over 2000 branches across the country with over 7500 employees. Also, the banking group has been at the forefront in facilitating the change from traditional to online/internet banking.

Currently, the bank has over 11 million online banking customers. As such, LYG is of utmost importance to the UK financial sector. It will continue to be the leader shortly. Before 2009, the banking group was known as Lloyd TSB. In the same year, Lloyd TSB acquired HBOS. The new business was renamed Lloyd Banking Group. However, the company has a much longer history that goes back to 1695 when its oldest brand, the Bank of Scotland, was incorporated through an Act of the Scottish parliament. Over the years, the banking group has acquired many different businesses to become the single largest financial institution in the country, thanks to its excellent leadership and governance codes.

ABN AMRO Group

Just like LYG, ABN AMRO is a group of companies trading under a common title and management. The group is based in the Netherlands, where it is one of the largest financial institutions. The bank has operations in 60 countries across the world. It was formed in 2010 following an amalgamation between ABN AMRO Bank NV and Fortis Bank. The combined entity is what is now referred to as ABN AMRO Group (hereafter referred to as simply ABN). Presently, ABN is the third-largest bank in the Netherlands with assets totalling to 390.317 billion Euros. In November 2015, the Dutch government publicly listed the company, thus changing its ownership from a state corporation to a publicly traded corporation (Aggarwal et al. 2011). Nevertheless, the state still holds a considerable stake in the group through one of the two significant foundations that form ABN’s chief shareholder units.

Leadership and Governance at LYG

LYG is a public company with many shareholders, including the government of the UK. However, over the years, the government had reduced its stake in the company from 43% in 2010 to 8.99% in 2016. Previously, the government had been engaged in a bailout for the banking group after its prospects collapsed in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. However, today, the principal shareholders in LYG are large institutions and mutual funds. According to Abreu and Gulamhussen (2013), the US investment company, Blackrock, is the biggest shareholder at LYG after buying most of the government stock.

At LYG, good corporate governance is recognised as the key to the organisation’s success. According to Ahmed (2015), corporate governance covers all the mechanisms and processes involved in the control of corporations. For this reason, the distribution of rights and responsibilities among LYG’s stakeholders is taken seriously. Key stakeholders of LYG include the board, managers, members, auditors, and regulators. Effective corporate governance must take into account the role played by regulators and auditors (Financial Reporting Council: The UK corporate governance code 2014).

Just like in all public companies, shareholders of LYG are recognised as the authentic owners of the company. Hence, they perform various ownership roles as provided for by the UK corporate law. They provide the requisite funding necessary for the company to pursue its strategic goals. Besides funding the company, shareholders have the duty of voting in the company’s annual general meeting (AGM) and special resolution conference. As such, the shareholders of LYG participate in the election of the company’s directors who are charged with its day-to-day operations. First, the board appoints the directors, although they have to be sanctioned by the shareholders through an election that is conducted during the AGM. Moreover, shareholders hold power to remove a director from his or her position through an extraordinary resolution. Sometimes, upon election, the shareholders may act as directors of the company.

According to the UK Companies Act of 2006, the director conducts the day-to-day management of LYG. At the helm of the company’s management are the board that is made up of a non-executive chair, executive administrators, and independent non-executive directors. The board is concerned with ensuring that the company achieves long-term success by putting in place an effective business strategy. Other roles played by the board include setting up remuneration policies and monitoring the organisation’s financial performance. Notably, the board is charged with forming committees that make recommendations on critical managerial decisions, including those that relate to internal control, risk management, remuneration, and financial reporting (Zalata & Roberts 2016). The committees are listed below:

- Audit Committee.

- Nomination And Governance Committee.

- Remuneration Committee.

- Responsible And Sustainable Business Committee.

- Risk Committee.

Leadership and Governance at ABN

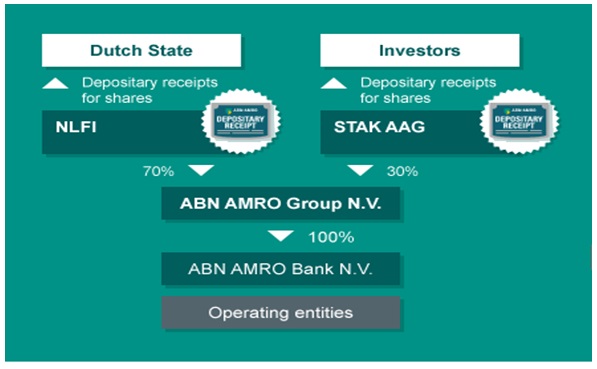

Before 2014, ABN was a state-owned corporation having been nationalised by the government as part of a bailout strategy that was adopted in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, which saw many financial institutions (see also, LYG) collapse. After five years of being funded by the government, O’Neill (2016) reveals that ABN was relisted at the national stock exchange (Euronext Amsterdam) as a publicly-traded company. Presently, two foundations, namely, NFLI and STAK AAG, hold all the share capital of the company. As at November 2016, NFLI was controlling 70% stock while the remaining 30% was in the ownership of STAK AAG. The two foundations have shares and depository receipts issued to ABN. Figure 1 below illustrates how the corporation’s funding is distributed between the two major financial institutions.

The last annual general meeting was held on 2nd January 2017. Just like LYG, the shareholders of ABN participate in decision-making through voting. As such, they vote to elect or remove directors. The voting rights of individual members depend on the size of equity that one controls in either NFLI or STAK AAG. Also, the Dutch state has a sizeable stake in the company through NFLI. The minister of finance who (being a shareholder of ABN) is also the chief regulator of corporations in the Netherlands put the government stake in NFLI in place to prevent conflicting duties. Through NFLI, the minister can exercise his or her shareholder rights indirectly, hence avoiding exerting unnecessary political influence in the company.

Similar to LYG, the shareholders of ABN do not interfere with the day-to-day company activities, which are instead handled by the elected board. In essence, a two-tier board, namely, the managing board and the supervisory board leads the group. The two boards work independently but in coordination with each other to create a productive business environment. Both NFLI and STAK AAG have equal membership and committees on both boards. The Managing Board is tasked with the management of the company. It performs tasks such as designing the company’s mission, vision, and strategy.

Additionally, it is the role of the managing board to ensure that the objectives mentioned above are achieved in the short and the long term. The Supervisory Board plays an administrative role over the managing board (Thomsen 2016). As such, its crucial responsibility is to ensure that the managing board performs according to the expectations of ABN’s stakeholders. Importantly, the Supervisory Board is charged with appointing members to the managing board. The shareholders then approve the members.

The provisions of The Rules of Procedure of the Managing Board dictate the functioning of the Managing Board. The rules determine both the internal structure of the managing board, as well as how it functions. Presently, six committees have been established under the said rules to be part of the managing board. The committees are:

- Group Risk Committee.

- Group Asset and Liability Committee.

- Group Transition Management Committee.

- Group Disclosure Committee.

- Group Central Credit Committee.

- Regulatory Committee.

Each committee is tasked with examining and providing recommendations on critical aspects of leadership and governance in the organisation. Besides, corporate governance at ABN is governed by four corporate values, namely, teamwork, integrity, professionalism, and respect. Out of this combination, the company has managed to rise in prominence within the Dutch financial sector and in over 60 countries. An important aspect of the ABN’s leadership and governance is that the management strives to achieve the standards set in the Dutch Corporate Governance Code (amended in 2009).

Differences between Governance at LYG and ABN

The two large banks operate within the same geographic region. The Royal Bank of Scotland, which is the main stakeholder in ABN, has its origins in the United Kingdom. However, despite the two banks bearing some similarities, including their size and unwavering commitment to shareholders, they also have fundamental differences regarding their leadership and governance. To begin with, ABN is led through a two-tier board while a single board steers LYG (Kroeze & Keulen 2013). The Dutch Corporate Governance Code requires that firms in the public banking sector will have both supervisory and managing boards (Thomsen 2016). Such provision is non-existent under the UK Governance Code, which only requires accountability in the way the board is appointed and elected. Another fundamental difference relates to the amount of control that the national governments exert on these banks. While the UK government only controls about 9% of LYG’s stock, the Dutch government has a significantly more significant stake in the ABN.

Conclusion

The post-2008 financial crisis taught governments to adopt strict governance codes for their respective banking sectors. This was after it emerged that ethical misconduct in the industry resulted in the crisis. The crisis greatly hit both companies, and their respective governments had to bail them out. Today, LYG and ABN operate strictly as per the principles of best practice contained in the UK and Dutch governance codes, respectively. A critical difference between how the two corporations are managed is that LYG has a single board while ABN is operated by a two-tier board.

Reference List

ABN AMRO: shareholder structure. 2016. Web.

Abreu, J & Gulamhussen, M 2013, ‘The stock market reaction to the public announcement of a supranational list of too-big-to-fail banks during the financial crisis’, Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 49-72.

Aggarwal, R, Erel, I, Ferreira, M & Matos, P 2011, ‘Does governance travel around the world? Evidence from institutional investors’, Journal of Financial Economics, vol. 100, no. 1, pp. 154-181.

Ahmed, A 2015, ‘Exploring the corporate governance in Lloyd’s and the Co-operative Bank: The role of the board’, Journal of Business and Management Sciences, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 6-19.

Financial Reporting Council: the UK corporate governance code. 2014. Web.

Kroeze, R & Keulen, S 2013, ‘Leading a multinational is history in practice: The use of invented traditions and narratives at AkzoNobel, Shell, Philips and ABN AMRO’, Business History, vol. 55, no. 8, pp. 1265-1287.

O’Connell, D 2016, ‘Leadership styles and improved governance outcomes’, Governance Directions, vol. 38, no. 4, pp. 202-206.

O’Neill, D 2016, ‘Zalm considers the scale of ABN AMRO’s ambition’, Euromoney, vol. 47, no. 564, pp. 70-73.

Thomsen, S 2016, ‘Nordic corporate governance revisited’, Nordic Journal of Business, vol. 65, no. 1, pp. 4-12.

Zalata, A & Roberts, C 2016, ‘Internal corporate governance and classification shifting practices: An Analysis of UK corporate behaviour’, Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance, vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 51-78.