The earlier image, dated 1908, by Lewis Wickes Hine, is titled “Rhodes Mfg. Co. Spinner. A moments glimpse of the outer world. Said she was 11 years old. Been working for over a year. Lincolnton, N.C., 11/11/1908” (Hine, Rhodes Mfg. Co. Spinner. A moments glimpse of the outer world. Said she was 11 years old. Been working over a year. Lincolnton, N.C., 11/11/1908). It shows a young girl gazing out the window across from a rank of spinning equipment stretching into the unseen distance. The impression is of isolation and yearning for daylight, freedom, and a childhood foregone, in the midst of a machine-dominated world.

The setting is a thread factory in North Carolina, where stacks of spools reach well above the child’s head and indefinitely in all directions. The only lighting comes through tall windows. The child is Caucasian, slender, pre-pubescent, and any age from nine to teenaged, depending on her experience of malnutrition, a phenomenon often documented by Hine (Sampsell-Willmann 383). Her shorter skirt, while modest, signals childhood rather than adulthood. Her hair is indifferently groomed, and her clothing rumpled, suggesting a lack of parental attention and time at home.

She leans very slightly towards the window. Her facial expression is wistful, curious, but calm. She is alone in the picture – perhaps in the whole building. It is not obvious what her function is. This is neither a classroom nor a play area, so she is either an interloper or a worker.

The photographer shoots from well back from her, pointing straight down the line of machines, and lit solely by the tall window. The foreground is a bit less well-focused than either child or machines. As a black and white photo, there is no color. The shot may have been cropped to cut out anything detracts from the vertical wall and rows of machinery.

In this photograph, the artist is both an artist and a commentator. He has captured a child who is young enough to be expected to be outside playing or learning in a classroom or from a parent or elder. Hine was aware of children’s appropriate need for play and wonder (Seixas 383). This is a picture of lost childhood and lost connection with a loving, nurturing, caring parent (a parent who, the viewer could infer, is also working long hours and has no extra energy for parenting), resulting from exploitation of people of all ages.

The slightly later photograph by Lewis W. Hine is titled “Silk Spinner,” and is dated ca. 1908-1937 (Hine, Silk Spinner). It shows a slightly older girl actively and clearly involved with a giant spinning machine. The ‘bob’ haircut of the girl suggests that this was taken in the 1920s.

The setting is next to a huge machine stretching up above the young woman’s head and surrounds her. This is, according to the title and to the context, part of a thread spinning factory. The machines are not obviously in motion, but the girl is doing something to, or with, the machine – perhaps making an adjustment to the mechanism.

The young woman in the photo is older than the one in the other photo but is also Caucasian, reminding the viewer that exploitation is not limited to African Americans. Showing little bosom, she could be an adolescent or young adult. Her adult haircut gives the impression that she is more mature. Her smock is decidedly unglamorous. She has no makeup, but makeup would have been rare in that decade for a young person anyway. Her expression and body posture are pensive and serene. In fact, her attitude toward the machine seems almost casual. This suggests that this might have been posed rather than a candid shot. She is touching the machine lightly, moving, or checking on one of the many small levers that stick out from the machine. The girl is thus actively at work but also appears to be posing for the photograph.

Photographer Hine chose to shoot quite close to her, although not in a true close-up. He shows only the girl and her spot at the machine, nothing else in the area. Again, as far as the viewer is concerned, she could be the only human being alive in the factory space. The machine is her only visible companion. Unlike the other photograph, the shot does not show the line of the machines, but just the one. The source of lighting is unclear but is more uniform than the other one. There is no color, as this is black and white.

This photo does not tug at the heartstrings quite as strongly as the other one. However, it shows her near-total alienation from the work. She is baby-sitting a huge machine. The viewer asks what the girl’s purpose is here. Here the commentary is on the nature of work, rather than on the extreme youth of the girl doing the work.

These two pictures both make a comment on work in slightly different ways. The older one focuses more on the unfairness of child labor. It also notes the use of women for menial tasks. The newer one draws the viewer’s attention to the meaninglessness of the work, but it, too, highlights the use of women in repetitive jobs. The difference may be the result of the fact that in 1920, the industry had given many more people conveniences and comforts that made factories seem less evil. Additionally, Peter Seixas points out that Hine’s aim in the first years of his career was explicitly anti-child labor (Seixas 381). He asserts that Hine’s approach changed after World War I and reflected the changing aims of the people and organizations for whom he worked.

The photograph by Dorothea Lange titled “Southern Pacific Railroad Billboard near Los Angeles” or “Towards Los Angeles” is dated 1937 (Lange). It shows two male figures walking along a highway next to a billboard advertising train travel. It makes an ironic comment on the uselessness of the advertisement to the men who cannot afford anything.

The setting is a deserted desert landscape which the title informs the viewer is near Los Angeles, California. There are the suggestions of electric poles in the background, and the road cut is forbiddingly deep. A billboard is prominent in the near background, as well. The viewer does not see their faces, but they are clearly tired, having in the case of the left-hand man dropped his shoulder, and in the case of the right hand, the man slung his bag over his back to relieve the strain. Given the date during the height of the Great Depression, they are probably headed to the Los Angeles area in search of work. They are on foot either because of poverty or a misfortune that has robbed them of any other means of transportation. They are probably open to hitch-hiking.

The shot is somewhat low, which confirms for the viewer that the billboard is not an accidental inclusion, but one of the key players in the story. As in the series of photos satirizing the National Association of Manufacturer’s billboards, the artist is questioning the assumptions underlying the sign (Guimond 115). The lighting is brilliantly sunny and fades out all but the most salient features of the people and the objects and the landscape. The depth of field is shallow in spite of the apparently endless vista. There is no color in the photo and probably little color in the scene. The message is bitterly ironic, forcing the viewer to consider the gap between the haves and the have-nots, and the pressure of media to consume.

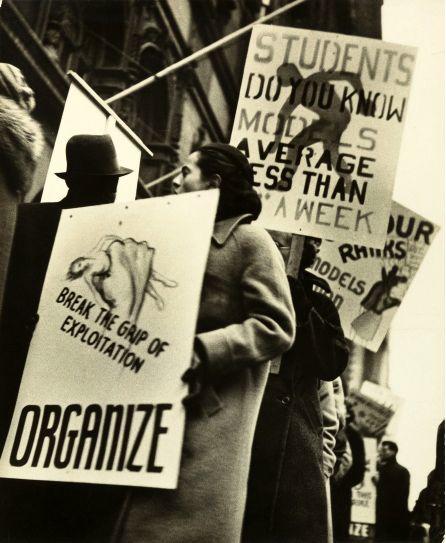

The other photo, “Break the Grip of Exploitation,” by Alexander Alland, is dated from 1938 (Alland). It displays a civil demonstration against the exploitation of artist’s models. Both women and men carry signs with clever images and pointed messages regarding the low pay of such workers.

The setting seems to be an urban area, plausible because it is usually in cities that large numbers of artists’ models can be found. However, the focus is so tightly on the demonstrators that the background is not very prominent, but it resembles the modern building of the Art Students League in Manhattan. The call to students suggests a correct match. The individuals in the photo are male and female and of uncertain ethnicity. The woman visible in the foreground could be from many different ethnic groups. It is not clear whether these are models or artists or concerned other citizens. They are dressed for cold weather, and appear entirely uninterested in the photographer, but rather focused on their signs, and presumably, their chanting. They are marching in a seemingly tight circle displaying their signs.

The shot is from below and seems heavily cropped to eliminate the context. The viewer does not see the sky or the street on which this is occurring. The lighting is natural and daylight. There is no color, as this is black and white.

The signs in the photo are themselves are miniature works of art, including reasonably skillfully drawn human figures. This is a kind of self-referential use of art. In order to make a plea to art students to consider the humanity and the needs of the models that make their work possible, the demonstrators use artworks, albeit mere sketches.

The two photos both make commentary on current social and economic problems. They note the differences between those who have power and resources and those who do not. However, the photos are different in that one is a landscape with unidentified figures in it, and the other is a mass of figures with practically no landscape. The meaning of both is enhanced by the text and images of the signs shown in each.

One subject of the Lange photo is the economic dislocation caused by the Great Depression, suggested by two laborers presumably seeking work. The Alland photo reflects the impact of the Great Depression as well but also clearly focuses on a more universal and continuing problem of economic exploitation of the powerless. Although this is a problem that is still being faced today by, for example, highly replaceable employees at big-box retailers, or marginally legal immigrants storefront nail salons, Alland was highlighting it in an unexpected industry, the seemingly privileged world of art students.

Ansel Adam’s photograph titled “Calisthenics [sic]. Manzanar Relocation Center, California. 1943” shows a young Asian-appearing girl engaged in organized exercise (Adams). She is with other young people, seen against a wide sky. It is one of a series of pictures taken by Adams of the War Relocation Center that interned Japanese-American citizens during WWII.

The setting is unclear. However, the title signals the location, which is a desert racetrack converted into a detention center. The site is a sere and desolate plain below the Sierras.

The figures are young girls of apparently Asian ethnicity, presumably residents of the Manzanar War Relocation Center. They are dressed in tidy American clothes, with neatly cut and groomed hair in Western styles. They are smiling and engaged with the activity, and the central figure is performing her exercises flawlessly. It is impossible to see the larger context, but the girls are spaced evenly to avoid hitting each other. They are doing arm exercises of the sort familiar to most Physical Education classes.

The background is left out, both by the angle, which is from slightly underneath the observer’s eye level, and upward, and the tightness of the shot. The close-in shot creates a shallow depth of field. There is no color. The face and the body of the central figure are thus highlighted.

This shot shows a girl of clearly Japanese ancestry, dressed and groomed in the entire Western outfit, cooperating in a Western-style P.E. class. This emphasizes that she is an American and should not be treated as an enemy. Adams is clearly trying to show how normal, American, and harmless those of Japanese ancestry is, and therefore how ludicrous their treatment is.

Bob Manbo’s photograph of little girls in colorful kimonos dancing in the relocation center where he lived was taken sometime after 1942 (Manbo). It showed girls dressed in a mixture of Western and Japanese costumes. The girls are engaged in a traditional activity but are clearly Americanized in their habits and dress.

The setting is the internment center. It is not really visible in this shot. The figures are the children of the internees. They are presented from the rear, but they are behaving naturally and un-posed, participating in either a dance or a game. They are all wearing American shoes and American hairstyles, combined with vibrant Japanese kimonos, and a few American dresses. The nature of the dance or game is not clear but is something that they are happy to do if they are perhaps a bit unsure of the details of where to move and what steps to take next.

Manbo shot them from the rear so that their identity will be unknown. They are seen as a bouquet of bright flowers. They form a central clump of color in an otherwise drab and uncertain background. Though Manbo may not have had a message, they do send one. These girls are keeping their lovely traditions alive while they braid their hair and wear sneakers. They are Americans of Japanese descent, not enemies.

Both photographs are the same in that they both convey the message that Japanese Americans are first and foremost Americans. They show the silliness and paranoia of the relocation effort by showing how human, how assimilated, how normal these people are. These two photographs differ in that one is taken by a professional, contracted to document this activity, while the other is taken by a skilled amateur who is living the experience. As a result, Manbo’s shots are more casual and more personal. The shot of the girls probably includes many that the photographer knows or even is related to, whereas, for Lange, all of her subjects are unknown before this assignment. Lange finds sweet faces and captures them, while Manbo finds friends and relations and preserves them (Duke University Center for Documentary Studies). Both, however, as evidenced by the shots themselves, reveal deep distress with the whole internment effort, distress that has reverberated through to later generations of Japanese-American artists, for example, in the work of Roger Shimomura (Greg Kucera Gallery).

Works Cited

Hine, Lewis Wickes. Rhodes Mfg. Co. Spinner. A moments glimpse of the outer world. Said she was 11 years old. Been working over a year. Lincolnton, N.C., 11/11/1908. National Archives. Web.

Hine, Lewis Wickes. Silk Spinner. George Eastman House, Rochester. Web.

Sampsell-Willmann, Kate. Lewis Hine as Social Critic. Jackson: University Press of Mississipp, 2009. Web.

Seixas, Peter. “Lewis Hine: From Social to Interpretive Photographer.” American Quarterly 39.3 (1987): 381-409. Web.

Alland, Alexander. Break the Grip of Exploitation. The Jewish Museum. 2015. Web

Guimond, James. American Photography and the American Dream. Charlotte: University of North Carolina Press Books, 1991. Web.

Lange, Dorothea. Towards Los Angeles: Southern Pacific Railroad Billboard Near Los Angeles. Library of Congress. American Photography and the American Dream. Washington : University of North Carolina Press, 1937. Print.

Adams, Ansel. Calesthenics [sic]. Manzanar Relocation Center, California. 1943. Library of Congress. Web.

Duke University Center for Documentary Studies. ” Colors of Confinement: Rare Kodachrome Photographs of Japanese American Incarceration in World War II.” 2015. Duke University Center for Documentary Studies. Web.

Greg Kucera Gallery. “Roger Shimomura | An American Diary series, 2002-2003.” 2015. Greg Kucera Gallery. Web.

Manbo, Robert. Girls in Kimonos at Internment Center. Japanese-American Photographers and the Internment Experience. 2015. Classroom lecture. Web.