Introduction

- Vulnerability of a population is defined by access to health care and overall health outcomes (Grabovschi, Loignon, & Fortin, 2013).

- Health policies aim to coordinate delivery of healthcare services, financing, and other practices while considering a broad range of health determinants.

- The Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) is an example of an effective policy that allows meeting the needs of a vulnerable population.

As stated by Grabovschi, Loignon, and Fortin (2013), the term “health care disparities” refers to “differences in the quality of health care – in terms of access, treatment options, prevention and health outcomes – across groups that reflect social inequalities” (p. 94). Population groups that are at risk of limited access to high-quality care are defined as vulnerable; it is clear that effective policies should be implemented to ensure better quality of life for vulnerable individuals. In light of these facts, in this presentation, I would like to discuss the role of the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), a component of U.S. health policy regulating different mechanisms for the financing, insurance, and rendering of individual-level medical services for children. During the policy review, I will talk about CHIP’s impacts on nursing practice and changes that could be made in the policy to make it more applicable to nursing today.

Policy Description

- Target population: uninsured children (aged 0-18) from lower-income families and not eligible for Medicaid.

- CHIP and Medicaid complement each other to provide insurance to both lower- and middle-income children (He & White, 2013).

- States have flexibility in designing their CHIP eligibility criteria.

- Typical CHIP eligibility criteria:

- Children between 0 and 18 years old,

- Families having annual income up to US $44,000 per 4 members,

- Income cutoffs between 200 and 300 percent of the federal poverty level (He & White, 2013).

The CHIP provides public healthcare coverage for uninsured children who are not eligible for other insurance options. The policy primarily focuses on lower-income families that do not have access to employer-sponsored insurance and who, at the same time, earn too much to enroll in Medicaid but cannot afford private insurance. As noted by He and White (2013), “CHIP and Medicaid are layered programs, in the sense that CHIP eligibility begins where Medicaid eligibility ends and extends to higher income levels” (p. E3).

KEY features

- Provides expansive benefits, including dental care, hearing and eye exams, and so forth.

- Allows meeting special care needs:

- Physical therapy,

- Speech therapy,

- Occupational therapy, and so forth.

- Reduces out-of-pocket expenditure (Paradise, 2014).

Unlike many private insurance programs, the CHIP provides a more expansive list of benefits for children, such as dental care (Paradise, 2014). Moreover, Paradise (2014) notes that “of key importance for children with special health care needs, all CHIP programs cover physical, occupational, and speech and language therapies, often without limits” (p. 1). Overall, the CHIP offers strong financial protection for lower-income families and their children and reduces out-of-pocket expenses to a minimum.

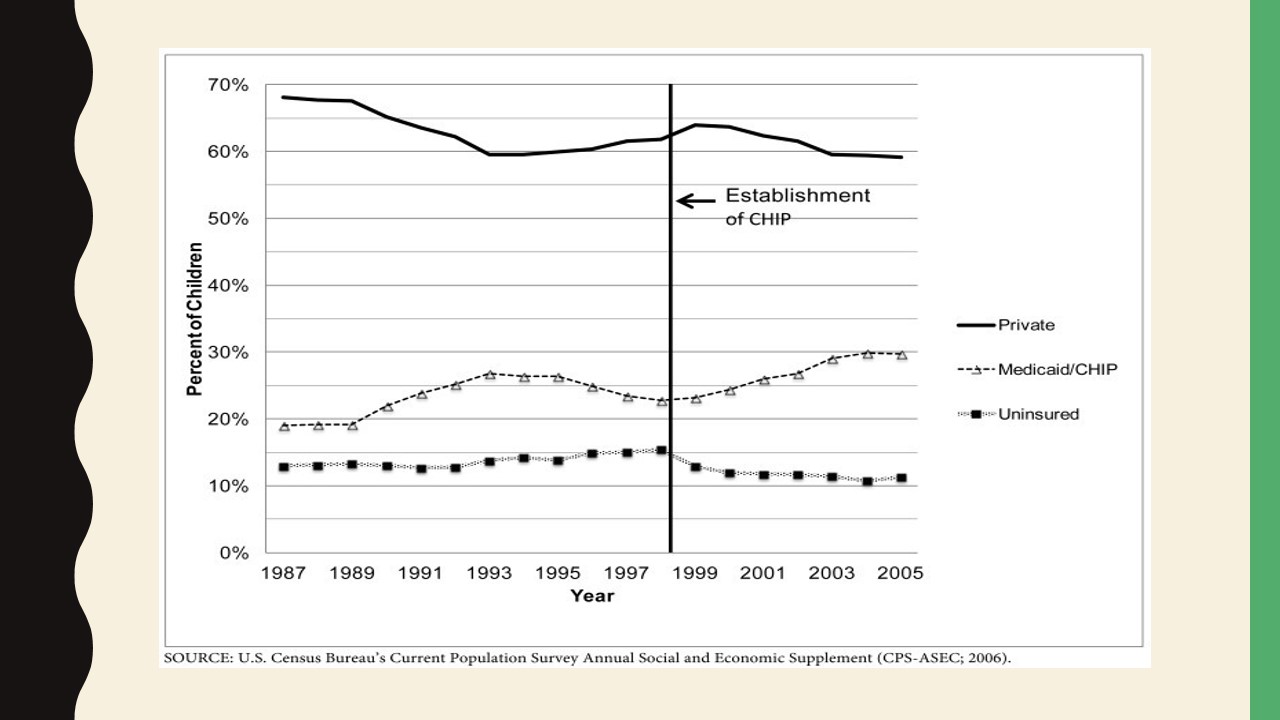

As stated by Bailey et al. (2016), CHIP “was informed by evidence that uninsured children have significant unmet healthcare needs,” and the program partially became responsible for “the uninsured rate among children in the United States (US) dropping from 14% in 1997, when CHIP began, to 7% in 2012” (p. 947). The exhibit presented on this slide was created by He and White (2013) with the use of data provided by the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement. The vertical line indicates the point in time when the CHIP was enacted and marks a decline in the share of uninsured children and an increase in the public health coverage rate in the same population group.

Vulnerable Population: Lower-Income Individuals

- Lower-income people are exposed to a greater number of environmental hazards:

- Limited access to healthy eating options,

- Poor housing conditions,

- Substance abuse,

- Life in disadvantaged neighborhoods, and so forth.

- Lower-income individuals interact less with healthcare practitioners due to a lack of insurance coverage and tend to suffer from chronic illnesses more frequently (Joszt, 2018).

As mentioned previously, vulnerable population groups are comprised of individuals with limited access to health care. Individuals belonging to these groups are also at risk of poor health outcomes due to various detrimental environmental influences. Such features are easy to find in lower-income families, who often cannot afford medical assistance and may fail to maintain a proper quality of life due to disadvantaged socio-economic conditions, affecting their food choices and stress levels, limiting their choices for accommodation to inadequate housing, and so forth. Statistics show that low-income people are more prone to develop chronic conditions and tend to have more comorbidities and severe symptoms than those with higher-income status (Joszt, 2018). Moreover, individuals from racial and ethnic minority groups are also disproportionally represented in the given vulnerable population (Joszt, 2018).

Vulnerable Population: Children

- Children are not “small adults.”

- Since children’s body systems are in the process of developing, they should avoid exposure to adverse environmental factors.

- Medical care for children should be timely and age-appropriate.

- Children are dependent on adults in medical decision-making (Joszt, 2018).

The vulnerability of children in terms of health care is primarily defined by their developmental needs. Joszt (2018) states that environmental hazards affect children’s health to a greater extent than that of adults because the bodies of the former are undergoing the process of growing. Thus, children are more likely to experience lifelong problems due to long-term exposure to adverse factors. Therefore, access to age-appropriate, high-quality medical care and supervision is essential for the pediatric population. Furthermore, due to their legal status, children are highly dependent on adults and cannot make independent informed decisions, which also indicates the necessity for proper health monitoring by practitioners.

General Policy impacts

- The CHIP reduces the rate of racial and ethnic disparities in access to health care among children by covering

- 52% of Hispanic children,

- 56% of Black children,

- 26% of White children,

- And 25% of Asian Children.

- 87% of eligible children were enrolled in the CHIP in 2011 (Paradise, 2014).

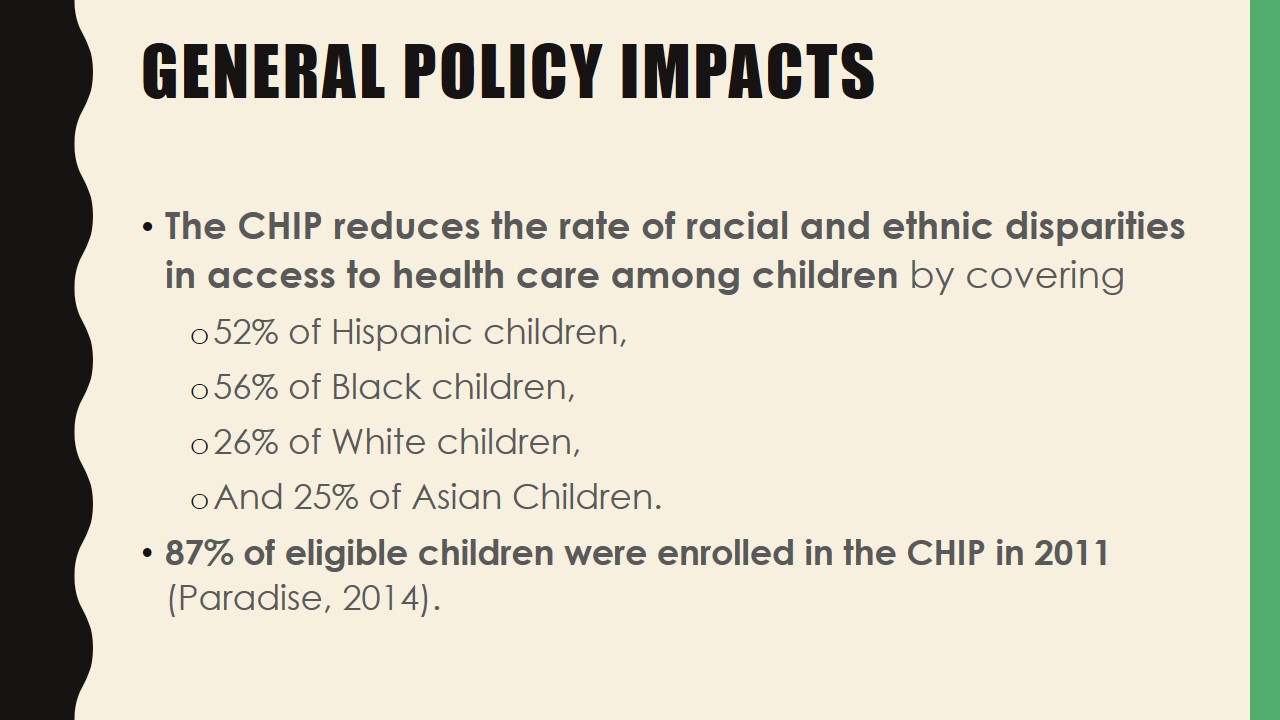

According to statistical data, “participation in Medicaid and CHIP among eligible children averaged 87% nationwide in 2011” (Paradise, 2014, p. 4). Regardless of the fact that both participation and retention rates differ from state to state, it is clear that the number of eligible low-income children who stay enrolled in the CHIP remains significant. It is worth noting that the CHIP is playing a particularly important role in healthcare coverage for individuals of color who are at a higher risk of low-income status. As Paradise (2014) states, together with Medicaid, the CHIP covers 52% of Hispanics and 56% of Blacks compared to 26% of Whites.

Impacts on health

- Increased rate of healthcare service utilization, especially primary care and dental care (Bailey et al., 2016).

- Greater access to preventive care:

- Long-term health benefits (illness prevention),

- Lower hospitalization and mortality rates,

- Better cost efficiency (Leininger & Levy, 2015).

Besides a significant increase in the number of insured children, the CHIP has resulted in an overall greater amount of healthcare service utilization in the population of interest. As stated by Bailey et al. (2016), children commence using pediatric primary and dental care services more within twelve months after gaining insurance due to easier access to medical care. Their study of pre- and post-coverage behaviors reveals that the rate of primary care visits and dental visits increased twofold within the period of one year (Bailey et al., 2016). Moreover, Leininger and Levy (2015) note that insurance increases the use of preventive services, which leads to long-term favorable impacts on health and cost efficiency even when these effects are not immediately noted.

Benefits beyond improved health

- Improved social and emotional functioning,

- Better long-term educational attainment,

- Decreased school drop-out rate (by 5%),

- Increased college enrollment and completion rates (Paradise, 2014).

Research evidence makes it clear that enrolled children show improvements in social, emotional, and academic functioning within two years of obtaining coverage (Paradise, 2014). As a result, they exhibit better performance at school and improve their long-term educational attainment. Noteworthily, the drop-out rate in newly insured high-school children has been shown to decrease by 5%, whereas college enrollment increased by up to 1.5% (Paradise, 2014). These data demonstrate that insurance-mediated health improvements affect individual functioning in various areas of life.

Policy Effects on Nursing Practice

- CHIP is leading to a greater need for nurse specialists.

- This fact emphasizes the importance of dealing with current workforce shortages in nursing as the U.S. pediatric population is expected to reach 84.6 million by 2025 (Betz, 2009).

- Major factors contributing to staff shortages:

- Lack of educators,

- High turnover,

- Inequitable distribution of the workforce (Haddad & Toney-Butler, 2019).

- School nurses can play a vital role in assisting families with gaining access to health care.

- They serve as liaisons between children and their primary healthcare providers.

- The need exists to provide school nurses with necessary resources and include them as school leaders in order to perform this activity more efficiently (National Association for School Nurses, 2019).

Similar to the Medicare program launched in 1965 that resulted in an increased number of hospitalized older adults and a greater need for nurses in acute care settings (Cherry & Jacob, 2012), the CHIP has led to an increased need for nurses specializing in pediatrics. At the same time, the “nursing profession continues to face shortages due to lack of potential educators, high turnover, and inequitable distribution of the workforce” (Haddad & Toney-Butler, 2019, para. 1). Researchers predict that the demand for pediatric nurses will continue to rise. According to estimates provided by Betz (2009), there will be 81.6 million children aged 0-17 in 2020 and 84.6 million in 2025 in the United States, about 14% of them having special healthcare needs. It is clear that with greater CHIP-facilitated access to health care, not all of these individuals will be able to receive high-quality service if the workforce shortage is not eliminated.

The CHIP is also inducing an increased need for nurses in such community settings as schools. The National Association for School Nurses (2019) states that, as part of their efforts to promote healthy lifestyles in students, school nurses should be empowered to assist children and families to access health insurance. While it is valid to say that every nurse should be able to identify individuals who are potentially eligible for the CHIP and give them appropriate referrals to agencies, school nurses may play an essential role in helping families access health care because they can interact with students on a more regular basis compared to clinical nurses.

Historical Overview

- 1997 – CHIP establishment with the purpose to expand public coverage and decrease the number of uninsured children,

- Enacted by Title XXI of the Social Security Act and created by the Balanced Budget Act of 1997.

- Key supporters and sponsors:

- Senator Ted Kennedy;

- Senator Orrin Hatch;

- First Lady Hillary Clinton;

- February 1999 – 47 states set up CHIP programs.

- April 1999 – 1 million children were enrolled in the CHIP in different states.

- First Lady Hillary Clinton played a major role in the promotion of the CHIP and improvement of public awareness.

- The main objective of the outreach campaign was to increase the number of insured children to 5 million by 2000 (Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania, 2008).

The CHIP was part of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 and came into force under the statutory authority of Title XXI of the Social Security Act (National Conference of State Legislatures [NCSL], 2017). It was created in response to President Bill Clinton’s comprehensive healthcare reform that he proposed in 1993 and that failed to get much support from the government and the public. The CHIP was sponsored by Senators Ted Kennedy and Orrin Hatch and was substantially supported by First Lady Hillary Clinton. According to He and White (2014), the main goal of the program was and is “to lower the number of uninsured children by expanding public coverage” to include the vulnerable population at issue (p. E4). In 1997, the CHIP became the biggest taxpayer-funded coverage expansion for children since 1965 when Medicaid was launched.

With Hillary Clinton’s efforts and active promotion of the CHIP, by February 1999, 47 states established CHIP programs, and by April of the same year, approximately 1 million eligible children obtained coverage (Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania [APPC], 2008). In addition, the Clinton administration funded an outreach campaign in order to increase the number of insured children to 5 million by 2000 (APPC, 2008).

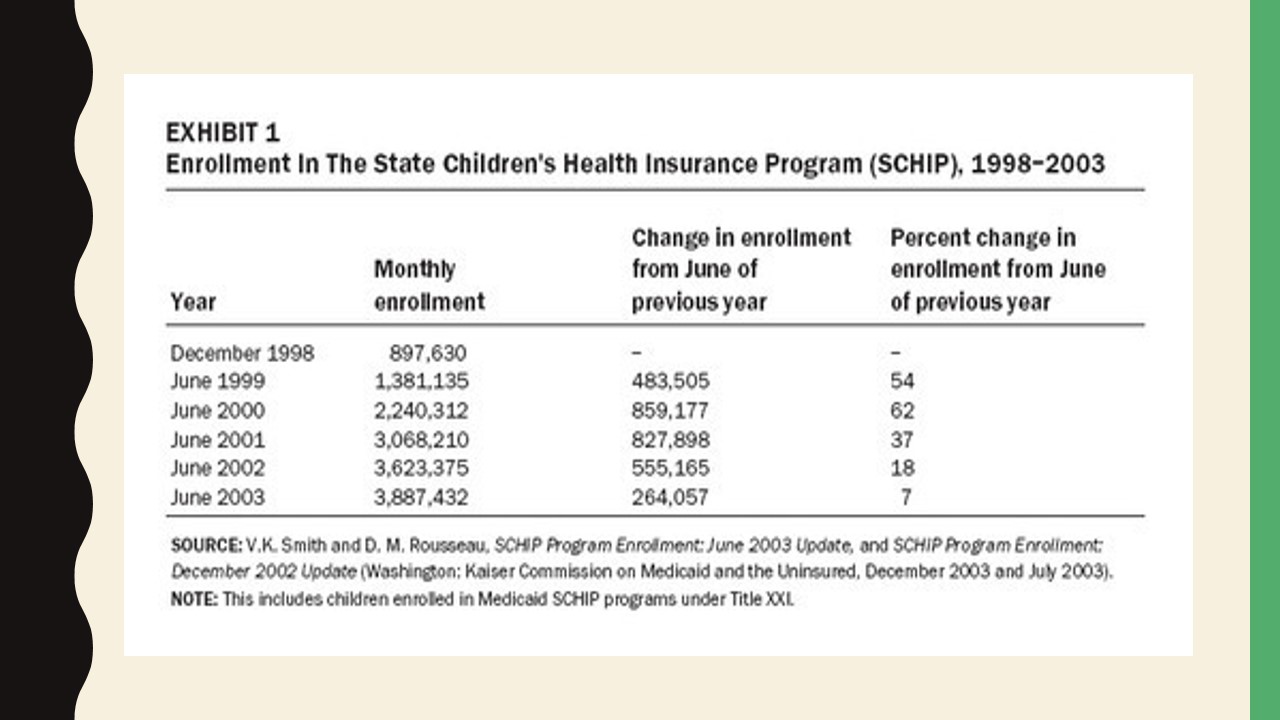

While this ambitious goal was not achieved, as Exhibit 1 demonstrates, the enrollment rates were particularly impressive between 1999 and 2000 (Kenney & Chang, 2004). According to recent data, the CHIP currently covers about 9 million children and 300,000 pregnant women (Reusch, 2018; Rovner, 2018).

The Chip Renewal

- February 2009 – President Obama signed the Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act, extending the CHIP until 2013.

- The CHIP continued to be extended for two additional years each in 2013 and 2015.

- December 2017 – The Congress passed a temporary spending bill, providing US $2.85 billion to maintain the coverage (Rovner, 2018).

- February 2018 – The CHIP was extended for 10 years through 2027.

- Key figures participating in the negotiation of the new budget bill:

- Senator Orrin Hatch;

- Senator Ron Wyden;

- The historic CHIP extension would allow savings of up to US $6 billion (Reusch, 2018).

The CHIP is a renewable program, which means that the government must pass temporary spending bills to maintain coverage each time the funding period expires. Initially, the program was authorized for ten years, and as noted by the NCSL (2017), “in February 2009, President Obama signed the Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2009, extending CHIP through 2013” (para. 1). Later, the CHIP was extended for two more years through the Affordable Care Act, and in 2015, the program was extended until September 30, 2017 (NCSL, 2017). Subsequently, the risk of loss of insurance coverage under the CHIP emerged as the government struggled to come up with a source of stable funding. After the last expiration date, a temporary spending bill passed in December provided the program with $2.85 billion, yet many states began to run short of funds as the sum was not enough to maintain coverage for 9 million children (Rovner, 2018). Recent threats to the CHIP have provoked heated public debate, even as the importance of the program has become increasingly apparent.

Luckily, the program was extended again in February 2018, this time for a period of ten years. Not only will this decision help keep children and pregnant women covered, but it will also result in significant cost savings. Reusch (2018) reports that “investing in CHIP for 10 years will yield $6 billion in federal savings, according to analysis by the nonpartisan U.S. Congressional Budget Office” (para. 5). This massive sum is projected to be used to support other child health and crisis relief programs as well as community health centers (Reusch, 2018).

Barriers to implementation

- Coverage does not always guarantee access to high-quality health care.

- Two of the main reasons:

- Workforce shortage,

- Practitioners’ unwillingness to work with children covered by Medicaid/CHIP due to low reimbursement rates.

- Insurance fee levels are correlated with the overall health outcomes in children.

Analysis of the literature reveals some significant barriers to effective CHIP implementation. For example, Leininger and Levy (2015) state that coverage does not always guarantee access. The main obstacle, which is also directly related to nursing practice, is a lack of healthcare providers, especially specialists who are willing to render services to children covered by Medicaid/CHIP at the low governmental rate (Leininger & Levy, 2015). Research findings also suggest that low reimbursement rates associated with public coverage are correlated with poorer health outcomes in children with public insurance compared to those with private insurance (Leininger & Levy, 2015). Therefore, it is essential to research various organizational and administrative factors and come up with an appropriate solution that is cost-efficient and, at the same time, will generate enough benefits for both practitioners and patients.

Other necessary changes

- Better outreach campaigns are needed to enroll more eligible individuals:

- About 5 million eligible children currently remain uninsured (“Closing the health insurance gap,” 2013).

- Collaboration between different professionals and organizations is necessary to ensure better linkage of families to insurance agencies.

While the CHIP’s impact on the overall coverage rate is undeniably good, a significant number of children remains uninsured. According to recent statistics, about 8 million U.S. children are currently uninsured, while approximately 5 million among them are eligible for various state and federal health coverage programs (“Closing the health insurance gap,” 2013). Thus, it is necessary to establish lasting collaborative relationships between clinical and community organizations in order to increase enrollment rates and ensure that all eligible children are provided with coverage. For example, school counselors and nurses have beneficial effects on different aspects of children’s health, and school-based health centers specializing in preventive services usually have sufficient information resources to reach out to eligible individuals (Leininger & Levy, 2015). It is possible to recommend that nurses working in different settings should engage in networking in order to enhance outreach results within certain communities.

Nurse roles in CHIP Implementation

To assist families in gaining access to coverage, nurses should:

- Gain awareness of the CHIP eligibility criteria in their state,

- Implement principles of family-centered care:

- Develop trustful and cooperative relationships with parents,

- Facilitate information exchange,

- Take into account multicultural differences of families (Festini, 2014).

In order to fulfill the CHIP’s mission and purposes, nurses must become able to identify families who are potentially eligible for the program. Therefore, they should explore background information related to the policy, learn about eligibility criteria in their state, and obtain the contact information of state agencies for families’ use. In addition, they must develop strategies and communication approaches that may help in detecting eligible children, which may vary depending on the setting where the nurse is working. However, in any event, implementing the family-centered care model is particularly important in pediatric nursing. Since it promotes cooperation between parents, encourages the open exchange of information, and aims to consider multicultural peculiarities of families, it can assist in informed decision-making regarding coverage potential (Festini, 2014). Moreover, it is suggested that in order to bridge insurance gaps, nurses must arrange and volunteer at community events targeting uninsured individuals (“Closing the health insurance gap,” 2013). Such practices facilitate building rapport with community members and help to raise their awareness.

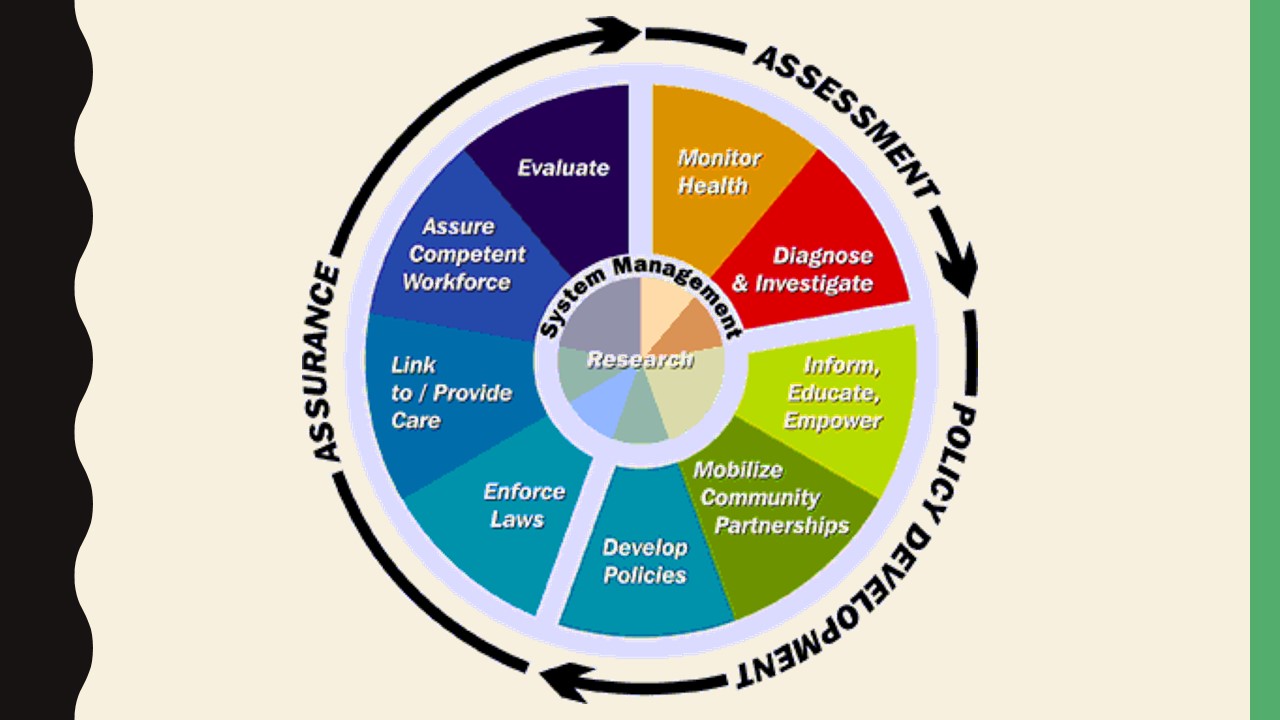

In order to promote solutions that would eliminate barriers to CHIP implementation and ensure better access to health care in the vulnerable population, nurses should be advocates. Overall, to advocate for any policy change, a nurse may employ the nine policy development stages presented on the slide; notably, research is at the center of the learning cycle. Any policy change initiative can benefit from high-quality evidence. Therefore, extensive and thorough research of any issue, whether an exploration of better reimbursement options or support for longer-term CHIP funding, should be carried out.

Nurse Roles in Implementation of Changes

- Conduct research on possible solutions to existing problems involving the vulnerable population’s access to health care.

- Use obtained research evidence to substantiate arguments in advocacy and lobbying campaigns.

- Build professional credibility through continual self-improvement and education.

- Develop networking skills and collaborate with interprofessional teams to foster desired changes at the organizational and community levels.

In addition, Yoder-Wise (2011) recommends that nurses develop their political and lobbying skills. In order to influence policy changes, a nurse should necessarily develop professional credibility, which is attainable with sufficient experience and as a result of continual self-assessment and education. It is equally important to have well-developed networking skills and be able to communicate effectively with diverse stakeholders and organizations. Overall, prior to trying to influence policies at the national level, it is helpful to start with promoting favorable changes at the organizational and community levels.

Conclusion

- The CHIP has resulted in a significant decline in the rate of uninsured children since 1999.

- Direct outcome: more frequent utilization of medical services.

- Effects on nursing practice:

- Greater need for pediatric nurses has emerged.

- Organizational and administrative barriers to higher-quality care and access to medical services are more evident.

- Major nurse roles:

- Networking and volunteering for better family outreach,

- Research and advocacy for organizational changes.

The conducted analysis revealed that CHIP establishment has helped reduce the rate of uninsured children from lower- and middle-income families to a significant extent since 1999. Currently, the program covers nearly 9 million U.S. children and is associated with more frequent utilization of medical services in general. However, the CHIP has not only impacted the vulnerable population of interest but has also affected the sphere of nursing practice by provoking a greater need for a competent workforce. As the number of insured children has increased, the obstacles to effective rendering of care has become more apparent. These include workforce shortages and organizational and administrative issues, such as service reimbursement, which prevent practitioners from working with children more effectively. Therefore, besides engaging in various family outreach practices, nurses must advocate for necessary organizational changes that would foster easier implementation of the CHIP and compliance with its mission.

References

Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania. (2008). Giving Hillary credit for SCHIP. Web.

Bailey, S. R., Marino, M., Hoopes, M., Heintzman, J., Gold, R., Angier, H., O’Malley, J. P., … DeVoe, J. E. (2016). Healthcare utilization after a Children’s Health Insurance Program expansion in Oregon. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 20(5), 946-54.

Betz, C. L. (2009). The nursing shortage, pediatric and child family nursing. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 21(2), 85-87.

Cherry, B., & Jacob, S. R. (2012). Contemporary nursing: Issues, trends, and management (5th ed.) St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Closing the health insurance gap. (2013). Web.

Festini F. (2014). Family-centered care. Italian Journal of Pediatrics, 40(Suppl 1), A33.

Grabovschi, C., Loignon, C., & Fortin, M. (2013). Mapping the concept of vulnerability related to health care disparities: A scoping review. BMC Health Services Research, 13, 94.

Haddad, L. M., & Toney-Butler, T. J. (2019). Nursing shortage. Web.

He, F., & White, C. (2013). The effect of the children’s health insurance program on pediatricians’ work hours. Medicare & Medicaid Research Review, 3(1), E1-E33.

Joszt, L. (2018). 5 vulnerable populations in healthcare. Web.

Kenney, G., & Chang, D. I. (2004). The State Children’s Health Insurance Program: Successes, shortcomings, and challenges. Health Affairs, 23(5), 51-62.

Leininger, L., & Levy, H. (2015). Child health and access to medical care. The Future of Children, 25(1), 65-90.

National Association for School Nurses. (2019). Patient protection and Affordable Care Act: The role of the school nurse. Web.

National Conference of State Legislatures. (2017). Children’sHealthInsuranceProgramoverview. Web.

Paradise, J. (2014). The impact of the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP): What does the research tell us? Web.

Reusch, C. (2018). Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) renewed for a decade!Children’s Dental Health Project. Web.

Rovner, J. (2018). CHIP Renewed for six years as congress votes to reopen federal government. Kaiser Health News. Web.

U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (n.d). Children’sHealthInsuranceProgram (CHIP). Web.

Yoder-Wise, P. S. (2011). Leading and managing in nursing (5th ed.) St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.