Abstract

Mega-events in sports are ordinarily meant to showcase the prowess and supremacy of some sportsmen and women who take part in them. However, a relatively unexplored area in this analysis is the impact that these events in host communities, cities, and countries. This paper fills this research gap by investigating the perception of the residents of Tianjin, China, regarding the impact of the China National Games on their city’s image. From the outset of this study, three core areas of Tianjin’s image are explored. They include the economic, environmental, tourism, and sociocultural image of the city.

These key areas of analysis are encapsulated by four research questions, which seek to find out the environmental, economic, socio-cultural, and tourism impacts of the China National Games in the city. These four research questions aim to meet the main goal of this paper, which is to investigate the perception of Tianjin’s residents regarding the impact of the China National Games on the image of the city. The research strategy used to meet this aim is based on the case study research approach, which is supported by the collection of data using a triangulation technique that involves gathering data from interviews, surveys, and desk research.

Based on the responses obtained from the aforementioned data collection techniques, this paper argues that the China National Games have a positive impact on the economy of Tianjin. The same data collection methods help to affirm a positive impact of the games on the sociocultural and tourism sectors of the city. Nonetheless, the respondents sampled in this review were unsure about the impact of the games on the environment of the city. This lack of surety permeated throughout the three centers of data collection. Thus, the researcher deduced that, out of the four areas of analysis, the environmental impact of the games was most contested. Future research should explore this area of study further.

Introduction

Background of the Study

Today, many cities around the world are relying on the popularity of different types of mega-events to improve or sustain their regional and global images (Nunkoo & Smith 2015). Often, countries aggressively bid to host these mega-events because they want to attract people from different parts of the world to spend their money on their local economies, market their core attributes, and boost their image (Quinn 2013).

Commonly, studies have focused on the economic benefits of hosting mega-events and neglected others (Nunkoo & Smith 2015; Quinn 2013). These benefits emerge from increased spending, which could be done in several ways, including increased demand for food, car hire services, accommodation, and the likes.

Different researchers have used different criteria to classify mega-events. Most of them agree that they often attract huge crowds (because they are characterized by a high number of people from diverse backgrounds), occur within a specified time, have a high profile, and have a quantifiable economic impact (Presenza & Locca 2012; Quinn 2013). Different types of mega-events may take place in any given location.

Thus, the location of an event does not necessarily need to be a city; it may happen in a country, or even a specific region (Nunkoo & Smith 2015; Quinn 2013). Based on the uniqueness of the location, different typologies of mega-events exist. The common ones include sports events, cultural events, business events, and even religious events (Nunkoo & Smith 2015). Some of them take place within a few days, weeks, months, or even years. The Olympic Games and the World Cup are common global examples of mega-events.

Although there is little doubt that mega-events have an impact on the economy of host communities, the reputation of host communities is also under review. The kind of effect that these events would have on the reputation of host communities would largely depend on the media coverage given to them (Taks et al. 2013). Indeed, as Quinn (2013) observes, media coverage often shapes people’s image of a host location and its people. This is mostly true because more people watch or hear about mega-events from the media than those who physically go to witness what happens (Bailey 2015). Thus, image is a central concept in understanding mega-events.

The main purpose of undertaking this research is to investigate the residents’ perception of the impact of mega-events on the city of Tianjin, China. Tianjin is a port city of China’s mainland that is inhabited by millions of people from different cultures. The city is considered among the top six largest metropolises in the Asian nation (Ma 2017). Located in the country’s coastal mainland, national statistics show that the city is home to more than 15 million people (Wen & Zhu 2015). It is also considered home to one of China’s largest urban populations (Ma 2017).

About two-thirds of this population resides in the city permanently, while the rest is comprised of rural dwellers (Ma 2017). Most of the residents are of Chinese descent, while the minority groups are comprised of ethnic minorities living in Asia, such as the Mongols and Koreans (Ma 2017). The Han ethnic group is the largest in the city, comprising of about 97% of the population, while the Tujia ethnic group is the smallest because it comprises of about 0.03% of the population (Ma 2017).

Tianjin is perceived to be a diverse city because of its ability to attract thousands of new inhabitants every year (Wen & Zhu 2015). Based on the influx of people who come from diverse backgrounds and from neighboring Beijing, the city has gained the reputation of being welcoming to all people and also rich in history (Liu, Broom & Wilson 2014). These qualities are partly highlighted in the diversity of its student populations and suburbs.

The number of people who live and work in the metropolis is also more diverse than most cities in China, thereby making it exceptional in its ability to attract people who have different ideologies, beliefs, and values (Yu, Wang & Seo 2012). Different aspects of the city’s economy and politics have also been influenced by the diversity of the people and the opinions and culture they share about different aspects of life (Yu, Wang & Seo 2012).

The China National Games is one mega event in the city that will be held between 27th August 2017 and 8th September 2017. The event is expected to attract more than 12,000 participants who will take part in more than 30 sporting events. There will also be 417 events that will occur in the event (Ma 2017). These games have been deemed by some observers as an opportunity for older athletes to maintain their honor and for younger ones to stake their claim on the national if not international, stage (Ma 2017).

Based on these expectations, the China National Games are expected to have a significant impact on the city. Central to this assertion is the merger of perceptions and ideologies that shape the people and the image of Tianjin. However, as espoused earlier, mega-events in the city bring new economic, social, and even political influences that are difficult to quantify (Ma 2017).

Research Problem

Several kinds of literature have strived to explain the main tenets of the image as a concept in analyzing the impact of mega-events (Altinay, Paraskevas & Jang 2015; Bjeljac, Pantić & Filipović 2013). However, the current analysis has failed to delimit itself from four key tenets of the discussions. The first one is that the concept of the image should also include the perceived attitudes and impressions of the local people and not only those of international observers (Raj, Walters & Rashid 2013).

This limitation implies that most kinds of literature have only focused on understanding the international perspective of a city’s image and (almost completely) disregarding the fact that the residents’ awareness of the city, relative to their cognitive experiences and learning processes, also count towards the analysis. The second limitation is that the concept of an image should include the collective understanding of how people internalize an event, relative to the kinds of communication strategies adopted (Rojek 2013).

The third limitation of the researcher’s conception of the image is the obsession with the brand, as opposed to the factors contributing to the concept. Lastly, there seems to be a disconnect between people’s understanding of the impact of mega-events on cities and the salient attributes of their images (Bjeljac, Pantić & Filipović 2013).

The general weight of hosting a national event, such as the China National Games, in Tianjin could overwhelm most residents and even influence their lifestyle, or redefine their city’s image in ways that were never conceptualized before. Based on the city’s rich history of accepting new ideas, people, economic ideals, and social values, it is would be interesting to understand the impact that such games would have on the city’s image through the perceptions of the people that live in it.

To have a holistic understanding of how such games would influence the people, this study will adopt a multifaceted conceptualization of the effects of the games on the people by evaluating four critical areas of analysis – environment of Tianjin, the economy of the city, the Tianjin tourism industry, and the city’s culture. This focus is encapsulated in four research questions that will guide this study. These questions are also captured in the overall research aim of the research, which appears below.

Research Aim

To investigate the perception of Tianjin’s residents regarding the impact of the China National Games on the image of Tianjin, China.

Research Questions

The research questions that will guide this study appear below

- What is the perception of Tianjin’s residents about the impact of the China National games on their sociocultural environment?

- What is the perception of Tianjin’s residents about the impact of the China National Games on their economy?

- What is the perception of Tianjin’s residents about the impact of the China National Games on the city’s tourism?

- What is the perception of Tianjin’s residents about the impact of the China National Games on the city’s environment?

Research Objectives

The objectives of this research are outlined below

- To determine how the China National Games affect the residents’ perception of their quality of life during and after the event.

- To identify the sociocultural impact of mega-events in host cities like Tianjin, as predetermined by residents.

- To understand how Tianjin residents relate the China National Games to the city’s image

Significance of the Study

The significance of this study is enshrined in the fact that researchers say few things could match the ability of sporting events to foster a sense of regional identity (Elling & Dool 2014). Based on this assertion, an investigation of the impact of how the China National Games in Tianjin would affect residents of Tianjin would go a long way in drawing people together to create a common sense of understanding regarding what matters most to them.

The value of such an investigation is partly manifested in how the 2010 World Cup in South Africa helped to bring people together and promote a common sense of identity for residents of the host nation (Tichaawa & Bama 2012). This common identity is partly supported by the fact that sports mega-events often help to transcend social and cultural boundaries that would have otherwise inhibited people from developing this common sense of identity (Heere et al. 2013).

Because such sporting events promote a common sense of purpose among the people, fostering one identity could help to provide a platform where residents of Tianjin would discuss some of the political, social, and economic problems affecting the city. In other words, this study is significant in providing a tool for the city to address some of its problems because people would be communicating from a common position where they want to foster a common identity for themselves.

Nationally, the findings of this study could be useful in promoting a sense of nationalism that would characterize Tianjin, and by extension, China. The development of such a strong sense of identity would be instrumental in nurturing and understanding and preserving the culture and ethos of the country, as it has been demonstrated in other nations such as South Africa when it hosted the 2010 World Cup or in Germany when it hosted the 2006 World Cup. Similarly, evidence of the significance of sports in such a setting exists in America where mega-events have helped to cement a sense of national identity (Tichaawa & Bama 2012).

The popularity of the Super Bowl is one such example because it has helped to crystallize a sense of national identity among Americans, better than any shared culture or values held by its citizens. By virtue of this assertion, the significance of this study hinges on the fact that it would help to promote a sense of common identity among the residents of Tianjin. The development of this identity is also intertwined with the ability of its residents to promote the social capital that binds them.

Scope and Limitations of the Study

The scope of the study will be limited to understanding the perceptions of residents of Tianjin regarding the key areas of the study discussed in this chapter. A key point to note is that only the views of people who live in the city will be sought, regardless of their nationalities, ethnicities, or other socioeconomic measures. The goal is to make sure that residents become the main points of data collection. Another attribute that relates to the scope of the study is the nature of the games that will be under investigation.

In other words, the scope of this study will mainly be limited to understanding the impact of the China National Games on the image of the city and not any other sporting event that may take place in the metropolis. These games happen every four years and emphasis will be made to investigate their impact on the city, mostly regarding the recent win by Tianjin to host it.

Lastly, the scope of this study will also be only limited to the city’s image and not any other aspect of its identity. This means that the scope of the study will only be focused on understanding how the China National Games affect how residents of Tianjin view or see their city. Key attributes of this concept (image) refer to how the games affect the city’s representation, appearance, and meaning.

The limitations of this paper will be largely influenced by the nature of the research questions, which strive to understand specific aspects of Tianjin’s society that could be influenced by the country’s national games. These areas are limited to the city’s cultural makeup, tourism sector development, economic development, and environmental record.

These four key areas of the analysis outline the limitations of this study. This fact means that there could be other aspects of the city’s political, social, and economic fields that could be affected by the games, but for purposes of this study, evidence will only be sought to understand how the city’s residents conceive the impact of the games on the four key areas of development, captured by the research questions. This limitation will also be mirrored in how the questions posed to the participants will be formulated.

Literature Review

This section of the paper presents a review of existing research studies that have investigated different aspects of the research questions. Key sections of this chapter highlight the conceptual framework used to conduct the study, and the impact of mega sports events in different communities that have hosted them, including the ramifications of doing so on their economic, social, environmental effects. Several theoretical issues that underpin this research are also investigated in this chapter. The subsection below explains the conceptual framework.

Conceptual Framework

The conceptual framework for this study will be based on the balanced scorecard technique. Although this model is primarily used in business (and more specifically in the field of strategic management), its principles have been proven to apply in the sociology field as well (Smith 2014). Simply, this technique selects a key set of financial and non-financial issues to weigh, or measure, the success of an organization (Fujii 2014).

It also posits that the true picture of an organization cannot be understood using only one metric of measurement (Fujii 2014). Thus, instead of applying only one measure of identity to a city, it is important to use multiple scorecards to understand its image. These scorecards largely refer to the key success factors for analyzing a city’s image (as applied in this study).

The balanced scorecard technique is applicable to this study because it could help to understand the concept of a city’s image from multiple perspectives. In other words, it is capable of providing readers with different measures of analyzing a city’s image. Through the analysis of these multiple perspectives, readers get to have a fast and comprehensive view of what is under investigation. Thus, the application of the balanced scorecard technique has to be analyzed deeply and within the context of analysis (Fujii 2014).

Although this model has mostly been used to espouse “context” to mean an organization, in this study, the context will not be the organization, but a city. However, the key performance measures will be the main attributes of the city that define its identity. Thus, the city’s identity, if applied in the context of the balanced scorecard technique, could mirror the strategic outcome of an organization. Using the same logic, four key aspects of Tianjin’s image will define it – economy, culture, environment, and tourism.

Theoretical Review

Different studies have highlighted different metrics for understanding the impact of sporting events on host populations (Tresidder 2015). This paper has already shown that the balanced scorecard technique is one such approach that has analyzed sporting events based on four main criteria that include economy, culture, environment, and tourism. This technique has been lauded for its ability to encapsulate the agenda of a host nation, but, at the same time, people are cognizant of its limitations based on the fact that it cannot explain the holistic impact of the event on the people (Tresidder 2015).

While many studies have used the balanced scorecard technique to explain how sports events have an economic, physical and environmental impact on their host cities, others have claimed that the impact of such mega-events on the values and norms of a city’s residents should also be highlighted (Chirieleison & Montrone 2013).

The main limitation noted regarding the use of the balanced scorecard technique is its lack of proper measurement guidelines, considering it relies on multiple areas of focus for assessing community impacts (Deery, Jago & Fredline 2012). Particularly, the difficulty in balancing the different measures of analysis and assigning appropriate weights to them undermines the reliability of the technique. Nonetheless, researchers who have used the balanced scorecard technique to ascertain the impact of mega-events in cities point out that, such events have significant economic, social, and managerial impacts (Chirieleison & Montrone 2013).

However, the researchers point out that these influences are mostly contextual (Chirieleison & Montrone 2013). Moreover, they say these influences are both short-term and long-term, but more importantly, they have a contextual appeal because several external factors and structural alternatives have an effect on how mega-events influence host cities.

The contingency theory has also been used to understand the impact of sports events on host communities (Ziakas 2013). Similar to the balanced scorecard technique, this theory comes from a background of business studies because researchers have used it within the wider realm of understanding how organizational theories affect performance. It presupposes that certain contingencies affect how mega-events influence cities (Ziakas 2013). Some possible contingencies include technology and the environment (Chirieleison & Montrone 2013).

Particularly, studies that have investigated the impact of mega-events in Asian cities emphasize the importance of “context” in this analysis (Minnaert 2012). To demonstrate the impact of technology, as an example of a contingency measure in this assessment, we could use the example of Ziakas (2013) which showed how there was a decline in global audiences and sponsorship interest when Michael Schumacher and Ferrari dominated the 2002/2003 Formula 1.

To regain interest in the sport, organizers had to rethink the rules of the game, which affected how technology was employed in the event (Ziakas 2013). The main lesson learned from this example is the effect that technology could have in eliminating the “uncertainty factor” in sports, which is a “turn off “for most audiences (Minnaert 2012). Generally, this analysis explains the influence of the contingency theory in explaining how sports affect audiences.

Besides the balanced scorecard technique and the contingency theory, researchers have also used economic models to ascertain the impact of mega-events on host cities (Smith 2014). Some of these models include the input-output analysis technique and the cost-benefit analysis method. Another model that has been widely applied is the computable general analysis technique (Ziakas 2013). These three alternatives have significant advantages and disadvantages. Ziakas (2014) has provided a context for analyzing all of them – a center that could be used for further analysis.

Researchers have used these models to analyze the impact of different sporting events, some of which are not limited to the ICC Cricket world cup which happened in India in the mid 199s as well as the FIFA World Cup that happened in Japan in the early 2000s (Deery, Jago & Fredline 2012). These analyses point out significant differences regarding the impact of these events on host communities, in terms of their economic and social effects. The findings have been used to crystallize some of the differences noted between the impact of sporting events in advanced western cities and those located in developing countries.

Impact of Mega-Events on Cities

According to Brown, Richards, and Jones (2014), mega-events are simply large-scale events that often occur within a specific period in a city’s, national, or global calendar. However, their occurrence is often within a short time, usually less than a year. Typically, mega-events have a serious and long-term effect on the reputation and history of a host city or a nation (Nunkoo, Ramkissoon & Gursoy 2012). The infrastructural resources deployed to facilitate the occurrence of such events often lead to a showcase of a city’s capability, including a possible long-term settlement of some populations, usually through foreign investments (Minnaert 2012).

In a review of kinds of literature that have strived to provide a more comprehensive understanding of mega-events, Freeman (2012) provides a classification guideline defined by four main tenets that include the ability of a city to attract other people, the scope of media reach, cost of undertaking an event and the transformative impact it would have on a city.

Additionally, Butler and Aicher (2015) term the effect of mega-events in cities as being “ambulatory” because they often involve huge capital investments, appeal to a large population, are characterized by a huge impact on the built environment and often occur within a predetermined period. This assertion largely underscores the four dimensions of mega-events which are highlighted above.

Based on the above classifications, the China National Games in Tianjin fit the description of a mega event. This is because national games are both a social and cultural event that takes place periodically within the country, attracts a large media coverage (both locally and internationally), captures the imagination of a large audience, requires a huge capital outlay to implement and has a strong cultural and social impact on the host population.

The impact on the population is also diverse because it could have long-lasting environmental and political impacts on the city (United Nations Development Programme 2012). As Gallarza, Arteaga, and Gil-Saura (2013) argue, its psychological impact on the population cannot be ignored either. This assertion is consistent with a research study by the European Commission (2016) which investigated the impact of the European capital of culture in host cities.

Resident’s Perception on a City’s hosting of Sports Events

Most kinds of literature that have investigated the impact of sporting events on a country’s national image have borrowed their principles from research on corporate communications (Maennig & Zimbalist 2012). They have also shown that three factors are central to our understanding of this subject – image, reputation, and identity (Taks 2013). These studies have also demonstrated that some of the principles aspired to in communications research could easily apply to our understanding of regional images.

Here, the concept of “region,” as explained in some of these kinds of literature, mean political or administrative blocs, such as cities, provinces and even countries (Nunkoo, Ramkissoon & Gursoy 2012). The kinds of literature also draw comparisons between these regional blocs and companies by saying that both elements share unique similarities that would help to explain where some researchers have greatly borrowed from the corporate communications lens to explain social and political issues relating to a country’s or city’s image (Taks et al. 2013).

One area of similarity highlighted in some of these studies is the financial logic that different entities (such as cities or countries) follow. The studies also show that these entities need to appeal to a specific audience (Fredline, Deery & Jago 2013). The same entities are also similar because they are guided by visions, which are implemented using strategic directions implemented by people in leadership positions. However, the same kinds of literature also point out that companies differ from regional blocs because the latter’s leadership is often dictated by voters, while the former is often determined by the shareholders (Nunkoo & Smith 2013).

Based on this difference, the image of a city or country cannot be easily influenced using a top-down structure (contrary to companies that often influence or shape corporate image and reputation using a top-down approach) (Viviers & Slabbert 2012). Some studies have also pointed out that cities and countries do not get to determine the composition of their internal audiences (Nunkoo, Ramkissoon & Gursoy 2013).

The above findings show that the image of a city is essentially determined by the people who live in it (internal constituents) as opposed to the characteristics of it. Thus, by extracting this principle and applying it to the influence of mega-events in cities, we find that the image of a city is primarily determined by how the city’s residents perceive the event and not necessarily how other people perceive the city or what the features of the city should mean to other people. Deery, Jago, and Fredline (2012) support this narrative by saying that, when organizers want mega-events to benefit the locals of a city, their focus should be on local citizens and not on the tourists who will patronize it.

Nonetheless, as the interest on mega-events continues to grow in an environment characterized by increased recognition of their ability to promote a city’s image, some researchers advocate for the use of marketing strategies to reap the value that exists from hosting the events (Seetanah & Sannassee 2015).

More importantly, Grix (2014) highlights the need to pair an event with their hosting cities to establish that no aspect of the event obstructs the positive characteristics of the hosting city. This analysis brings our attention to the concept of congruity. It arises from a need to merge a city’s profile to the characteristics of an event. This analysis has been done within a marketing focus.

Marketing as Central to a City’s Image

Key to the aforementioned view is the understanding among many researchers that today, the market for global competitiveness in different aspects of social, political, and economic development is stiff. This fact is primarily supported by the perception that most cities of the world are offering almost similar competencies and “products,” in terms of educated people, a world-class infrastructure, and globally accepted systems of governance (Minnaert 2012).

To capture the imagination of its residents and citizens, cities are increasingly struggling to stand above the crowd by highlighting their prowess in “place image.” The “place image” is deemed central to how people would perceive a city because it captures different attributes of it, including the natural/physical characteristics of a city, its cultural identity, and regional gastronomy (among others).

The role of marketing seems to emerge as a central concept in how most arguments investigating city images have been shared and discussed. In fact, the understanding of “place image” is within Kotler’s 4ps of marketing which include – place, product, promotion, and price (Nunkoo, Gursoy & Ramkissoon 2013). A city’s image is subject to the concept of “place.” However, other researchers have also used other tools highlighted above for attracting people to their localities.

Some of these tools have been used to reduce the cost of living, and increase the appeal of an area for living and working families (Chirieleison & Montrone 2013). The justification for doing so is based on the understanding that if people value a city, its competitiveness will similarly increase. Thus, many cities often invest a lot of resources on mega-events because they strive to enhance their image and facilitate the benefits its people hope to achieve. Based on these goals, mega-events have been fertile grounds for cities to market themselves to their people and to the world.

Factors that Influence the Effects of Mega Events

In the last couple of years, cities and countries have been fiercely competing with each other to host some of the world’s most iconic sporting events (Nunkoo & Gursoy 2012). The same is true for the Olympics, World Cup, and similar events (Prayag et al. 2013). The fiercest competitions have been observed between cities and countries that bid for international events because of the global recognition associated with such events.

This view is partly supported by the works of Boukas, Ziakas, and Boustras (2013) which recognize that holding events in such cities is likely to increase a city’s or country’s image. Mega-events that have a cultural connotation to them also attract the same interests, particularly because hosting countries and cities recognize their economic potential (Weaver & Lawton 2013). This way, hosting countries are posited to benefit from a positive brand image and reputation.

However, as Gibson, Kaplanidou, and Kang (2012) point out, this is not necessarily the case because holistic reviews of several kinds of literature that have tried to measure the large-scale impact of mega-events on studies show that the outcomes are not always positive. This view emerges from studies that have shown that the benefits of mega-events may be hampered by the existence of inequitable social, political, and economic structures that may impede how the benefits of such events are shared (Vareiro, Remoaldo & Cadima 2013).

Some of the positive benefits of such events have already been highlighted in this chapter and they include a positive impact on a city’s culture, history, image, environmental, and economic wellbeing. Some of the negative impacts of the same events include an increased cost of living (mostly for residents living in the host cities), inhibition of a city’s cultural practices, negative environmental impact, and social disorder among other factors (Liu & Wilson 2014).

Although the above findings show both sides of the effects of mega-events on host communities, the first studies that tried to address the impact of events on host cities and countries focused on the impact of the Olympic Games on the same administrative units (Rojek 2014). The study by Ritchie and Smith is one of the first studies that delved into this area of analysis. It focused on understanding the impact of the Calgary Olympic Games on the host country and city (Nunkoo 2015). Held in 1989, the Olympic Games had a positive impact on the city (Nunkoo 2015).

This finding was advanced by both researchers who attributed this outcome to increased awareness by the people. However, they also cautioned that years following the completion of the event would be characterized by a significant decline in the image of the city (Nunkoo 2015). The researchers mostly used the willingness by tourism stakeholders to capitalize on the profile of the mega event as an instrument for attracting new clients by saying that a one-off event would not do much to accomplish this goal; instead, they needed to couple the mega event with small ones to create a sustainable stream of tourists (Nunkoo 2015; Andersson & Lundberg 2013).

The above assertion is partly affirmed by the view of Örnberg and Room (2014) and Grix (2013) who say that the overall success of a mega-event on a city depends on the ability of the organizers to plan and promote the events.

They also draw our attention to the need for cities to have a cross-cultural understanding of the impact of such games and similarly for the need for organizers to promote the community spirit of the events on the local populations (Nunkoo & Ramkissoon 2012). Most studies that have supported this view have largely been based on European investigations of the same research issue, as espoused by the works of the European Commission (2016) and Grix (2013).

Mega Sporting Events in Asia

Perhaps one of the most notable sporting events in Asia, and China, in particular, was the 2008 Olympics held in Beijing, China (Sugden & Tomlinson 2012). When the country won the bid to host the summer games, organizers and commentators said it was a good opportunity for people to discover China and learn about its people (Sugden & Tomlinson 2012). Although studies have shown varying views regarding the impact of this event on the country, their findings mostly differ, based on whose perspective is in question.

For example, the perspectives of athletes have differed from those of officials. Similarly, the perspective of spectators has differed from those of the media and organizers (Liu 2013). These differences are not necessarily critical to this review because it is important to point out that underneath the analysis is a swelling body of literature that has focused on investigating the impact of mega-events (often in the sports arena) in Asia.

This view is held by different researchers, including Li, Hsu, and Lawton (2015) and Liu (2013) who have argued that the past two decades has seen a significant shift in attitudes within the political and economic fields regarding the effect of these events on host populations and communities. Ziakas and Boukas (2012) start this discussion by pointing out that the mere clammer for the rights to host regional and global sporting events is an indicator that nations are increasingly determined to showcase their philosophies and commitment towards promoting sports.

Asia is a unique area of study because until recently, the sporting field has been largely deemed a platform for competing on a regional front (Li, Hsu & Lawton 2015). As highlighted in this paper, the sporting arena has gained a new image, as is witnessed through the strong interest of politicians and commercial entities when such games take place. Evidence of this fact exists in different parts of the continent. Singapore is one such example because sports have become a strong part of the country’s national identity in the 21st century (Ziakas & Boukas 2012).

To cement this fact, there is a wide range of participation programs instituted by shareholders in the industry. This assertion is further supported by the view of Butler and Aicher (2015) who say that sports have supported the creation of a national identity for citizens of Asian nations and also fostered a sense of national pride among several sportspersons who have outshined their competitors in recent years. Additionally, other commentators have alluded to the economic growth witnessed in the industry as another contributor of sports to the national growth of Singapore (Taks et al. 2013).

Based on these positive contributions of the sports industry to the prosperity of the nation, there are ongoing efforts by stakeholders to make the field a more sustainable one. The future of the sporting sector in the country is showing further signs of strength, as can be witnessed in the long line of mega-events that are set to take place in the country, as well as the growing interest by sponsors and commercial entities who are fighting for television rights and other opportunities to market their products and services (Ziakas & Boukas 2012).

Several kinds of literature sampled in this review highlight the need to conceive sports as a critical part of sustainable development roles (Li, Hsu & Lawton 2015). Those who hold this view argue that few industries have the global power seen in sports events (Li, Hsu & Lawton 2015). This fact is supported by statistics that show that the turnover associated with sporting activities is equivalent to 3% of the global economic activity (Prayag et al. 2013). Different parts of the world mirror this statistic, as is evident in the UK where the turnover witnessed in the sports industry is equivalent to the combined turnover of the food and automotive sectors (Prayag et al. 2013).

The unparalleled power of sports stems from the influence of major sports events that command global attention, such as the Grand Prix and the World Cup (Nunkoo 2015; Andersson & Lundberg 2013). Most South Asian countries also have a huge interest in cricket as a popular game. Economic gains made by the International Cricket committee also add to the narrative that the sporting industry is unrivaled and commands global attention because it receives more than $2 billion in sponsorships and from the sale of television rights (Nunkoo 2015). At the same time, it is important to point out the undue influence that corporate activity has on the sports industry because it has widespread social and environmental ramifications on the host populations.

Mainstream researchers have pointed out their reservations regarding the incorporation of sports-related research in conventional academic literature (Butler & Aicher 2015). Instead, they have shown that such research should be investigated in separate journals because they do not opine that the sector is generalizable (Butler & Aicher 2015). However, some observers disagree with this view by arguing that the sports industry has several distinct characteristics that make it internationally applicable and globally appealing (Chirieleison & Montrone 2013). The uncertainty surrounding sports outcomes largely explains why people have mixed and often highly charged emotional attachments to it. It also explains why some people exhibit unrivaled loyalty towards selected teams and players.

Role of Sports in China – Promoting a Healthy Lifestyle

According to the findings collected in this study, there was a clear assertion that the national games in Tianjin served two core purposes. The first one among some people is its emphasis on the need for the Chinese to promote the virtues of healthy competition, and physical fitness. The other outcome is that because of the prosperity that the games uphold, it has made it among the most well-attended mega-events in China. By virtue of these principles, the games seem to symbolize a greater national aspiration towards wellness, which, when translated loosely into English, means the need to promote good health.

This attribute is partially shared by many observers who have pointed out that since China started its Olympic journey in 1979, it has always aspired to get a strong sense of national pride (Yu, Wang & Seo 2012). This aspiration is partly shared by the fact that the country has and still adores most of its sports heroes. The same zeal is also being seen in the country’s preparedness to host similar Olympic Games in 2022 (Ma 2017). When the country hosted the 2008 summer Olympic Games, the same sense of national pride was witnessed among most citizens, as was reported in local and international media.

The above findings have a great bearing on the focus of this study because, although this paper only focuses on the perceptions of the residents of Tianjin regarding the China National Games, the national sentiments on the mega event also affect the same outcome. This finding is a deduction of what most researchers have alluded to when China held similar games in the past (Yu, Wang & Seo 2012).

Summary

This chapter shows that there have been several kinds of literature that have investigated the impact of different sporting events on different countries and cities around the world. Particularly, there has been a focus on interrogating studies that have undertaken the same research in Asia. Evidence of the same analysis in Europe has also been explored in this chapter, including the most common models adopted in the reviews. While these investigations show that the exploration of mega-events is no longer a new area of study, the contextual nature of these analyses cannot be ignored.

More importantly, it is difficult to generalize the effects of one mega-event on different parts of the world, different countries, or even different cities. As demonstrable in the literature analyzed, few studies have explored the impact of sporting events in China, beyond the 2008 Summer Olympic Games. More importantly, there is little evidence to show that researchers have tried to explore the impact of mega-events in Tianjin, with a special emphasis on the China National Games.

This study seeks to fill this research gap, by providing a contextual analysis of the impact of the same games on the city’s image. To this extent of analysis, this paper will use the balanced scorecard technique, as the conceptual framework, to investigate the impact of the China National Games in four key areas – environment, economy, social and cultural makeup of the city, as well as tourism.

These four key areas of analysis are highlighted in the four research questions that would guide this study. The questions strive to understand the perception of residents regarding the sociocultural impact of the China National Games in Tianjin, the economic impact of the games on the city, the environmental impact of the sports event, and the impact of the games on the tourism sector. The chapter below explains the research strategy that would be adopted.

Methodology

This chapter outlines the main research strategies that were implemented in answering the research questions. Key elements of this strategy that are highlighted in this chapter include the research philosophy, research methods, data collection strategy, validity/reliability of the study, and ethical considerations. These attributes of the study will help readers to interrogate the processes undertaken, or chosen, by the researcher to come up with the research findings.

Research Philosophy

Fox et al. (2014) say a research philosophy is a belief about how different aspects of an investigation should be carried out. The three main philosophies used in research include the positivist, interpretivism, and realism research philosophies (Fox et al. 2014). The realism philosophy often postulates that research studies should be guided by scientific evidence because objects could exist out of the reality of human thought (Fox et al. 2014). Comparatively, the interpretive approach looks at investigations as being aided by human beings, like actors in a wider investigative context of analysis.

It also strives to link our perspective of reality with the social roles of human beings. Researchers who often opt for this research philosophy prefer to use qualitative research approaches to collect and analyze data (Fox et al. 2014). The last research philosophy is the positivist ideology, which presupposes that human reality should be primarily based on some form of law or principle. Physical and natural researchers often like to use this philosophy in their studies (Fox et al. 2014).

They do so because they often prefer to adopt structured methods of research that would help them to answer specific research questions. The interpretive research method is the preferred philosophy for this study because it focuses on using human actors asocial agents of understanding a research phenomenon. The residents of the city of Tianjin would be the social agents for understanding the image of the city, relative to the influences of the China National Games.

Research Methods

There are two main research methods used in research studies. They include the qualitative and quantitative methods (Venkatesh, Brown & Bala 2013). The qualitative method is often used to collect subjective information, which does not have a set criterion of measurement (Brinkmann 2017). Comparatively, the quantitative research method is often used by researchers who want to collect measurable data. In this paper, the researcher used a combination of the two methods in a mixed methods research framework that combines the attributes of both techniques.

The justification for making this choice of research method is enshrined in the complexity of the research questions characterizing this paper because it would be difficult to use one approach to reliably capture the essence of each of the research questions. In other words, the four research questions asked in this study have both qualitative and quantitative aspects. Therefore, the use of one technique would mean that important information could be excluded from the overall findings.

Data Collection

The data collection strategy for this research involved three methods that included the survey method, interview method, and desk research. This triple data collection strategy is enshrined in a larger information triangulation framework chosen to strengthen the quality of data obtained in this study. The triangulation technique presents the three data collection strategies in a wider structure that aims to safeguard the quality of each piece of information collected. It appears below.

Survey

A survey is an instrument of data collection that involves the collection of systematic data. According to Fox et al. (2014), there are six main modes of conducting surveys. They include mobile surveys, online surveys, telephone surveys, mail surveys, face-to-face surveys, and mixed-mode surveys. In this paper, face-to-face surveys were used, where the researcher approached random people and asked them to take part in the study.

Thus, the researcher had to be physically present in the same environment and the respondents and his role included approaching people and asking them to take part in the study, as well as helping them to answer the questionnaires if there was a need to do so.

The researcher conducted the survey from 20th August 2017 – 1st September 2017 in five malls and shopping centers around Tianjin. They are Hisense Plaza, Tianjin Qingfang Shopping Mall, Jixian Gulou Mall, The Exchange Mall, and Binjiang Shopping Mall. These shopping malls are spread around the city and acted as the central data collection points to gather the views of the residents who live in different parts of the metropolis.

The researcher interacted with about 20 people in each of the malls, randomly. In total, 188 people agreed to take part in the study. Only two of those approached were not residents of the city and were not allowed to take part in the study because the data collected was only supposed to contain the views of residents of Tianjin. Respondents who agreed to take part in the study only took about 5 minutes (or less) to complete the survey questionnaire.

The survey was designed in a simple manner to facilitate data collection because it would have been difficult to convince many people to participate in the study if it took more than five minutes of their time. Thus, the survey had to be simple and address only a few issues related to the research phenomenon. Consequently, there were only four main issues asked. They were designed to address each of the research questions. The four key areas under investigation addressed the economic, sociocultural, tourism, and environmental impacts of the China National Games in Tianjin.

The surveys were designed using a 7-point Likert scale, which spread the respondents’ views across seven key response anchors – “strongly disagree,” “disagree,” “somewhat disagree,” “neutral,” “somewhat agree,” “agree,” and “strongly agree”. The data obtained from this survey were analyzed using SPSS software version 23. Generally, the survey method used in this study to collect data was representative of the quantitative aspect of the mixed methods research framework used in this study. The qualitative aspect of the research was represented by the interview technique described below.

Interview

The interview method was used as the second data collection instrument. It was designed to collect qualitative data or subjective information relating to the four research questions highlighted in the first chapter. Ten respondents were interviewed from 1st September 2017 – 6th September 2017 using a telephone. These respondents were experts in sports management, who mostly specialized in the Asian sporting arena. They were chosen using a purposeful sampling technique because of their expertise in sports management and their understanding of the social and cultural environments of Asian countries, relative to the impact of mega-events in local communities.

The respondents were selected from five consulting firms with a regional presence in China and Southern Asia. As will be explained in the ethical review section of this paper, privacy and confidentiality agreements prohibit the mention of their names. Nonetheless, each of the firms consulted provided two respondents each to make the sum total of the ten respondents who participated in the study. The interviews were conducted over a period of three weeks. The information collected using this method was analyzed using thematic and coding methods.

The justification for choosing the interview method was to have an alternative data collection method hinged on the fact that the information retrieved should be used to compare and contrast the data obtained from the survey method. Therefore, the survey method was the primary method of data collection, while the interview method was the secondary method of data collection.

Therefore, the emphasis was made by the researcher to allow the experts to explain some of the responses obtained from the surveys. In other words, some of the survey findings were shared with the experts who helped to make sense of them and give their additional views as well. Thus, the researcher was able to contextualize the findings and understand the views of the primary respondents regarding the impact of the China National Games in Tianjin.

Desk Research

Desk research was adopted as a complementary technique for collecting data. The main purpose of incorporating it in the study was to provide a historical and contextual understanding of the survey and interview findings. For example, desk research helped the researcher to understand what other studies which contain similar findings have said about the research topic.

Therefore, it was possible to understand areas of convergence or divergence between the current research and past research studies. Similarly, it was possible to compare the findings obtained from this study and what other researchers have found out about the impact of sports mega-events in other cities and countries.

Desk research was conducted by searching for and analyzing several research materials that were limited to books, journals, institutional reports, government reports, and credible websites. The articles were retrieved from several databases, including Google Scholar, Tnf Online, Sage Journals, and Emerald Insight. The keywords used to conduct the study were “mega-events,” “effects,” “cities,” and “sports.” This inclusion criterion was hinged on the date of publication. Articles that were published earlier than 2012 were excluded from the study. Similarly, those that did not fit the criteria of books, journals, or credible websites, were also excluded from the review.

Validity and Reliability

The validity and reliability of research studies are important issues to consider in making sure the findings of a study are credible. According to Hall and Roussel (2012), the validity of research refers to the ability of the instruments used to measure what they are supposed to measure. Comparatively, the reliability of research refers to the ability of a study to generate the same findings if done again.

The validity of this research will be safeguarded using the member check technique which requires the researcher to verify the findings of the data collection methods with their sources. In other words, the researcher had to provide the respondents with a copy of the summarized findings so that they could ascertain whether it represented their views, or not. Although all the respondents felt that the findings presented in this study represented their true positions, they had an opportunity to correct the researcher if they felt that their views were misrepresented or misinterpreted.

The reliability of the study was safeguarded by the use of multiple data collection methods, which are explained earlier (the triangulation technique of data collection). Basically, this method was used to cross-verify some of the information obtained in the study. The same advantages derived from the use of the triangulation technique in data collection were also instrumental in improving the validity of the study’s findings.

Ethical Considerations

The use of human subjects in this research came with several ethical implications for the researcher. These implications are highlighted as ethical issues and discussed below.

Privacy and Confidentiality: Privacy and confidentiality were important ethical considerations in this study because the respondents did not want their identities to be revealed during the study. This was particularly true for the interviews because the experts wanted to present their views anonymously. Their wishes were respected as is evident in the fourth chapter of this report, which presents their views anonymously. The respondents were also assured that only the researcher would have access to the information. This strategy was employed to prevent the possibility that the information gathered would be transferred to unauthorized persons.

Informed Consent: Informed consent refers to the willingness of respondents to participate in the study. All the respondents chose to participate in the study freely. This means that they were not coerced, intimidated, or paid to take part in the research. The interviewees were required to sign an informed consent form stipulating the above, but the survey respondents gave oral consent to participate in the study.

Data Storage and Treatment: The data obtained from the respondents were stored in a computer (in transcript format) and secured using a password that only the researcher had. Thus, no access to third parties as possible. The respondents were also assured that, upon completion of the study, the data would be destroyed.

Findings and Analysis

This fourth chapter of the study contains the findings of the three main data collection methods – surveys, interviews, and desk research. It also contains an analysis of the same data, relative to what other researchers have said about the impact of sports mega-events on host communities. The survey findings appear below.

Survey Findings

The SPSS technique helped the researcher to present and understand the findings of the survey by investigating the relationship between the four variables under investigation (economy, environment, tourism, and sociocultural) and the main dependent variable, which is the image of the city.

Frequency Tables

The frequency tables below were instrumental in understanding the perceptions of Tianjin residents regarding the impact of the China National Games on the economic growth, environmental sustainability, tourism growth, and sociocultural environment of their city. The findings of each of these variables appear below.

Economic Impact

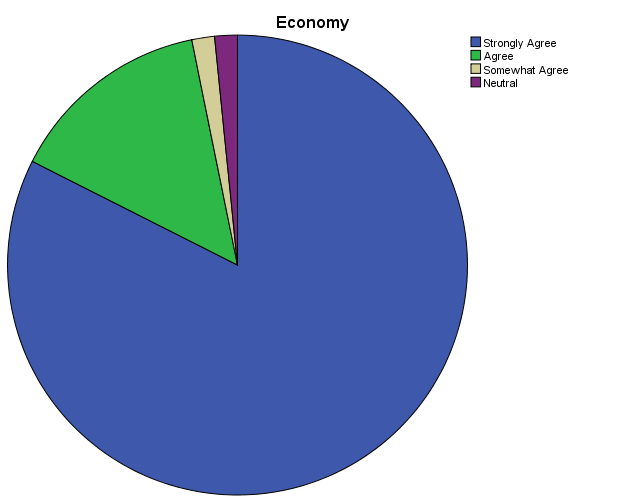

The table below shows how the residents of Tianjin polled when asked to state their views regarding the economic impact of the China National Games on their city.

Table 4.1: The economic impact of the China National Games in Tianjin

According to the table above, we find that 82.4% of the respondents sampled “strongly agreed” that the national games would have a positive impact on the economy of Tianjin. In terms of frequency, 155 respondents affirmed this view. Only 3% of the respondents were neutral when answering these questions. Since the percentage of people who believed that the games would have a positive impact on the economy were the majority, correctly, we could deduce that the residents of the city generally believed the games could not have a negative impact on the economy of Tianjin. The pie chart below summarizes the aforementioned findings.

In this analysis, it is also important to point out that the people’s response regarding the economic impact of the games on the city had the least standard deviation of all the four key areas investigated. This finding will be further investigated in subsequent sections of this chapter.

Sociocultural Impact

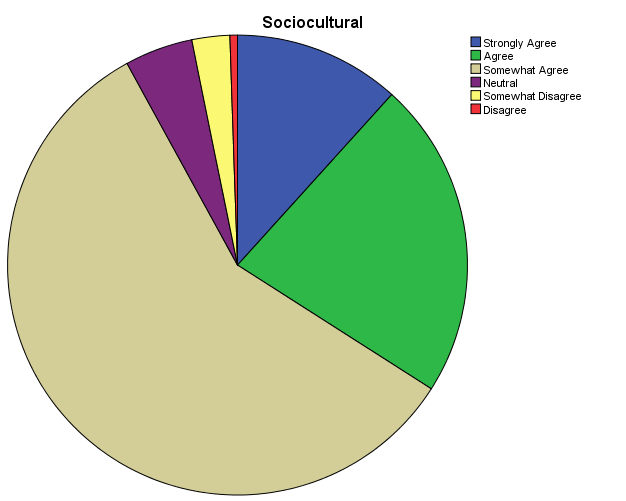

The table below shows the responses of the residents of Tianjin when asked to state whether the China National Games would have a positive impact on their city.

Table 4.2: Sociocultural Impact of the China National Games in Tianjin

According to the table above, most of the respondents (58%) “somewhat agreed” that the games would have a positive impact on the socio-cultural environment of the city. The second-largest population group in this study (22%) “agreed” that the games would have a positive impact on the socio-cultural environment of the population, while 5% of the population disagreed with this view. Based on these statistics, it is important to point out that the residents had varied views on this subject.

This is in sharp contrast to their view of the economic impact of the games on the city where most of them (82%) “strongly agreed” that the games would have a positive impact on the city. In fact, based on the 5% of residents who polled negatively to this question, we could deduce that there were some people who believed that the games could have a negative impact on the socio-cultural environment of the city. The pie chart below shows the distribution of their responses.

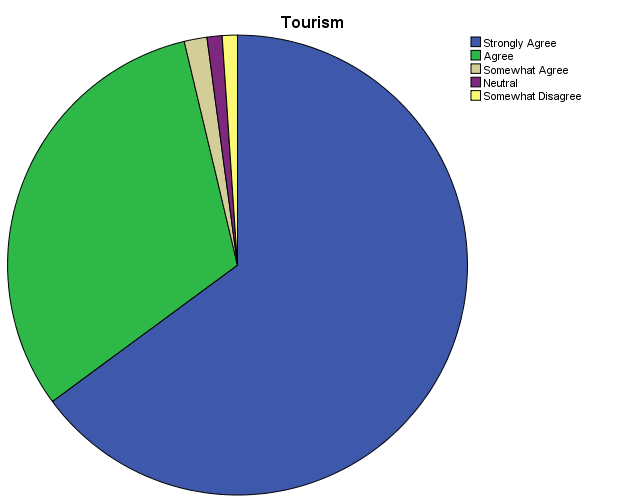

Impact on Tourism

Tourism was another key research area that constituted the survey questions. When the residents of Tianjin were asked to give their views regarding the impact of the China National games on the city’s tourism sector, most of the respondents strongly agreed that the games would have a strong impact on the industry. In fact, 64.9% of the respondents felt this way. Similarly, 31.4% of the population also “agreed” with the same statement.

Those who “somewhat agreed,” were “neutral,” or “somewhat disagreed” with this statement were few because they were all within the one percentile range. This finding meant that more than 97% of the residents of the city either “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that the games would have a positive impact on the city’s tourism sector. This statistic showed an overwhelming sense of confidence regarding the positive impact of the games on the city.

Table 4.3: Proportion of People who believe the China National Games would positively impact the tourism sector

The pie chart below also supports the findings mentioned above.

The pie chart mentioned above shows that most people were confident that China’s National games would improve the image of Tianjin through positive developments in the tourism sector.

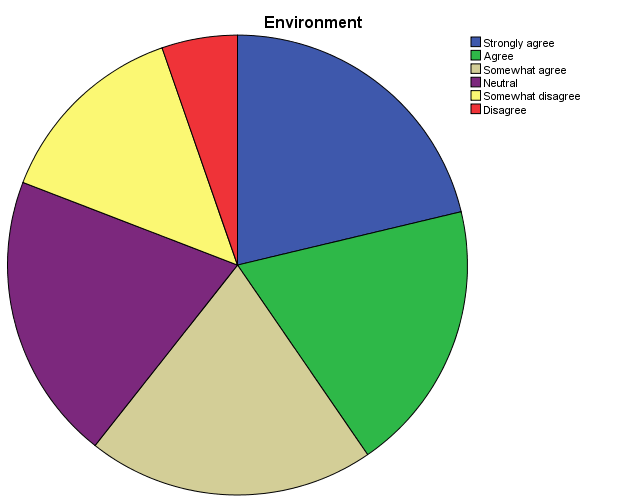

Impact on Environment

The last area of analysis undertaken in the survey was investigating the impact of the China National Games on the environment of Tianjin. This area of study elicited the most diverse responses from the respondents sampled. In other words, their views were spread and wide apart. In fact, none of the responses were able to gather more than 21% support from the respondents. The pie chart below depicts these varied responses.

This finding shows that the respondents were unsure of the impact of the games on the Tianjin environment. The table below further breaks down the figures representing the respondents’ views.

Table 4.4: Impact of the China National Games on the Tianjin Environment

Standard of Deviation of Responses

According to the respondents received from the participants, we found out that there was a minimal deviation in the respondents’ views regarding the impact of the China National Games on the economy of Tianjin city. The maximum deviation was noted in their views of how the games would affect the city’s environment because the standard deviation of this response was 1.513. The standard deviation for responses regarding the impact of the games on the economy was only 0.550. The table below summarizes the descriptive statistics associated with the dataset.

Table 4.5: Standard of Deviation for Variables

Chi-Square Test

The Chi-square test was used to find out if there was a relationship between economy and tourism as two independent variables because there was a general pattern in response where the participants strongly agreed with the questions asked in these two areas of questioning. The table below shows the outcome of the investigation.

Table 4.6: Chi-Square Tests

The table above shows that there is a statistically significant relationship between the economic impact and tourism impact because 80% of the samples have an expected count of less than 5, while the minimum expected count is 03.

Cross-tabulation

A cross-tabulation of sociocultural responses and environmental responses yielded the results below

Cross-Tabulation Findings

According to an investigation of the findings highlighted above, we find that the views of the respondents regarding the impact of the China National Games on Tianjin closely converged on two main areas – tourism and economy. Their response to the environmental impact of the games showed the greatest variation. Simply, it is possible to deduce that the respondents found it difficult to agree on whether the games positively impacted the environment, or not.

Since the survey was done face-to-face and involved shoppers who were going about their business, it was difficult to investigate why the residents of Tianjin polled the way they did. Consequently, it was important to share their views with the experts to find out whether they would explain some of the patterns observed. Some of their views are highlighted below in the interview findings section.

Interview Findings

Economic Impact of China National Games in Tianjin

When the respondents were asked to describe the impact of the China National Games would on the city of Tianjin, all the respondents said that the games would have a positive impact on the city. They mostly talked about the possible financial inflow of money that would improve businesses in the city through the infrastructural investments that would be made to spruce up sports facilities, as well as the money that would be enjoyed by the city’s businesses emanating from an increase in human traffic. One of the respondents said, almost obviously, that the games are often synonymous with a high number of hotel bookings, as well as a high number of occupancy rates in most accommodation facilities, which means that local business people are gaining economically by providing accommodation. Relative to this view, one of the respondents said,

“I do not see how anybody could argue otherwise because, around the world, such mega-events lead to an influx of people…spectators, organizers, or officials who would have to live in the host cities for the duration of the games. This means the money in the bank for the service providers. More importantly, it translates to a positive economic outlook for the city.”

Another respondent gave a personal example of his situation because he considered himself a service provider in Tianjin. He rents out three of his holiday homes to visitors. He further said,

“I live for such events because whenever there is a huge event in the city, my villa is always booked. I can easily budget for such money and in the same fashion, I believe many other people who do similar types of business in Tianjin benefit from the same.”

The respondents also said that the economy of Tianjin is bound to benefit positively through extra financial injections because of service-oriented industries that support the accommodation and hotel sectors. For example, they mentioned farmers as a key economic group in the city that benefits economically because there is a general high demand for food products that are used to prepare meals for visitors. The same group of workers also supplies restaurants and hotels, which in turn serve the city visitors. Typically, it is expected that this group of workers would benefit economically from their city hosting the national games. Cleaners, drivers, and security firms are also other service-industries mentioned by the respondents who would benefit from such games when they happen in the city.

Since all the interviewees believed that the China National Games would have a positive impact on the economy of Tianjin, it came as no surprise that they affirmed the survey findings, which showed a high number of respondents (over 90%) held the same view. In fact, most of the people surveyed “strongly agreed” that the games would have a positive impact on the city. The concurrences of the interview and survey findings on this matter draw our attention to studies by Gursoy et al. (2016) and Quinn (2013), which also hold the same position.

Sociocultural Impact of the China National Games in Tianjin

When asked to give their views regarding the sociocultural impact of the China National Games on the city of Tianjin, most of the respondents felt that the games would either have a positive or neutral impact on the culture and society of the city’s inhabitants. Those who believed that the games would have a neutral impact on the city’s social and cultural environment argued that there were not many differences in values and beliefs between the inhabitants of Tianjin and other cities of China. One of the respondents said,

“We are all one people. The same ideals we share in Beijing are probably the same ones valued in Tianjin. Perhaps, a more interesting scenario would be if we were holding international games in the city….say the 20008 Summer Olympic games – that had a notable impact on the city of Beijing…..My point is, if people of the same culture interact, not much cultural exchange would occur, right? However, if we have another situation where people have different cultures, sociocultural exchanges would occur, thereby making it more profound, but in this case, I do not think there would be a significant impact”

Experts who said the national games would have a positive socio-cultural impact on the city argued that the Chinese society is not particularly homogenous, as some of their colleagues argued, because they believed that the dynamism associated with the Chinese society would have a positive impact on Tianjin. One respondent who held this position said that the difference between Chinese urban cities and rural areas demonstrates this fact because people who live in the rural areas do not share the same ideals as those who live in the city.

The China National Games is a national event you know. If we are to use my example alone, don’t you think there is a possibility of a cultural mix between people who live in the cities and those who live in rural areas? I would argue there is, and in my opinion, any instance of cultural exchange is positive, regardless of which direction it goes.

Another respondent argued that there is a difference in how different cities in China operate. He said,

I have lived in Beijing and Tianjin, in as much as both urban centers may seem relatively similar; I believe they both give off different vibes. Beijing is a little more fast-paced than Tianjin and if people from both cities come together in one setting, there is bound to be some form of cultural exchange that would impact residents of both settings positively. This is just between the two cities; you could imagine what could happen if people or spectators from other cities interact with others in other settings…At the very least, there is going to be an exchange of stories, cultures, and ideals.

Generally, the above statements showed that some of the respondents believed the games would have a positive impact on the socio-cultural identity of Tianjin. However, when one of the respondents was shown the divide that exists between some of his colleagues, he said we should look at this issue differently. He argued,

The point here is not whether there are differences between Chinese people living in urban areas and rural areas, or those living in Tianjin and other cities in the country; the focus should be on the capacity of Tianjin to hold a national event and a mega one at that. I would argue that, by virtue of doing so, the city is demonstrating to the entire country that it could make everyone feel at home regardless of their social or cultural backgrounds. The point here is that by holding the events, Tianjin is indirectly telling the country that it has the capacity to accommodate people from diverse backgrounds.

The variations in opinion among the experts mirror the differences in views among the respondents sampled.

The Impact of the China National Games on the Tianjin Tourism Sector

When the respondents were asked to state their views regarding the impact of the China National Games on the Tianjin tourism sector, all of them agreed that the games would have a positive impact on the industry. All the respondents alluded to the positive impact of the games on the economy as part of the reason for this view. This assertion closely resembled that of the survey respondents who also said that the games would have a positive impact on the city’s tourism sector. When asked to explain if she detected a relationship between this response and that of the survey respondents, one of the experts said

See…. It is not surprising that they would poll that way because… I mean… it is the same strand. If visitors come to the city, they would eat, sleep, shop, and buy things from the local markets, which basically means they would be promoting the local tourism sector and, by extension, the economy.

The positive relationship between mega-events and positive economic growth through the tourism sector is not unique to these respondents alone because studies by Hall (2012) and Horne and Whannel (2012) have also affirmed the same fact. The same outcome has been affirmed in Europe through the Winter Olympic Games, the 2010 World Cup event in South Africa, and even in 2008 Beijing Summer games (European Commission 2016). In fact, few researchers hold the contrary opinion.

Many of them say that such mega-events positively impact the tourism sector (European Commission 2016). However, experts throw caution to this analysis by saying that only those cities, which have a vibrant tourism industry, benefit the most from such gains (European Commission 2016). Those that do not have such sectors, as part of their main economic activities, have nothing to boast about anyway.

Environmental Impact of the China National Games in Tianjin

When the respondents were asked to state their views regarding the impact of the China National Games on the Tianjin environment, most of them pointed out that the games would have a negative impact on the environment, with only two of them saying the games would not have an impact on the environment. Those who believed the games would have a negative impact on the environment said the surge in the human population in the city could possibly cause a strain on the environment, as more goods and services are demanded and suppliers struggle to meet the demand. In lieu of this fact, one of the respondents argued,

The games would definitely have a negative impact on the environment because I cannot fathom a situation where the massive infrastructural projects that would go on in the city would help to protect the environment. First of all, I predict a situation where there will be a high demand for fossil fuel to power the earthmovers that would be used in infrastructure projects. There would also be more taxis in business and more people in the city, leading to noise pollution, at the very least. Rowdy supporters and the likes….

As mentioned earlier, two of the respondents did not share the same view, one of them said,

As regards the environment, I do not think there would be any impact because these games are organized with international standards of environmental management, safety, and operations in mind. If there are any negative effects of the games in mind, I am sure they would be addressed. Similarly, I do not see how the games would also directly benefit the environment.

The above differences in views were also observed among the survey respondents who were almost evenly divided about the impact of the games on the environment.

Document Review

The document review process was mainly intended to shed more light on the key thematic areas anchored in this research. The four thematic areas focus on understanding the impact of the China National Games on the economic, sociocultural, environmental, and tourism sectors of Tianjin. The findings gathered from these thematic areas helped to shed more light on the interview and survey findings. They appear below.

Impact of Games on Environment

Since there was a general lack of consensus regarding the impact of the China National Games on the environment of Tianjin in both the interview and survey findings, it was important to investigate what other researchers have said about the impact of mega-events on the environment. An analysis of this issue by Nunkoo and Smith (2015) shows varied opinions regarding the effect of such events on the environment.

Studies that demonstrate that mega-events have a positive impact on the environment show that mega-events are occasions for national and international game organizers to demonstrate globally accepted standards of waste management and resource utilization, which should typically have a positive impact on the environment (Nunkoo & Smith 2015; Quinn 2013).

Those that hold a contrary view demonstrate that mega-events lead to the depletion of resources used to host them in the first place (United Nations Development Programme 2012). Based on these findings, it is plausible to assume that this area of research seems to share the same division as that witnessed in the interview and survey findings.

Impact of Games on the Economic and Tourism Sectors

The document review findings regarding the impact of the China National Games on the economic and tourism sectors of Tianjin show no differences from those mentioned in the interview and survey findings. In fact, excerpts of studies done by Karadakis and Kaplanidou (2012) and the United Nations Development Programme (2012) show that such mega-events almost automatically have a positive impact on the tourism and economic sectors of a city or country.

Several economic articles attribute this phenomenon to the foreign or direct capital inflows from organizers to host communities (Örnberg & Room 2014; Grix 2013). The main issue many researchers are grappling with today is to understand whether everybody in the city is able to feel the positive economic effects of the games (Örnberg & Room 2014; Grix 2013). However, this concern is out of the scope of this study.

Impact of Mega-Events on the Sociocultural Environment

The document review process showed that the impact of mega-events on the socio-cultural environment of a city is mostly affected by people’s social values and attitudes (mostly towards globalization). This view is held by researchers such as Kim et al. (2015) and Latkova and Vogt (2012) who point out that the impact of mega-events on the sociocultural environment mostly depends on who you ask. Generally, such studies have shown that communities could benefit from a cultural influx of people and their ideals if people interact frequently in mega-events (Kim et al. 2015; Latkova & Vogt 2012).

However, certain studies have shown that some conservative communities are against cultural exchanges because they deem them to be a threat to the community ideals (Le, Polonsky & Arambewela 2015). These assertions could be partly used to explain why there was a relatively noticeable standard of deviation regarding the views of the Tianjin residents on this matter.

Summary

This chapter summarized and analyzed the findings received from the interviewees, surveys, and document review processes. The views gathered from these data collection methods helped to investigate four key issues affecting the image of Tianjin – economic growth, environmental sustainability, socio-cultural development, and the tourism sectors. These four thematic areas were developed in line with the balanced scorecard technique which was the main conceptual model in this paper.