Artifacts

Eastside Heritage Center (“Bellevue History” para. 1)

The image in question can be interpreted as a hint at the possibility of the sustainable use of natural resources by the residents of the city. The image, clearly made in the first half of the previous century, incorporates the hopes for urbanization that would, later on, turn into threats for the sustainability of cities and the appropriate use of natural resources.

Depicting women working in the field, the picture in question can be considered an encouragement for agricultural development and, therefore, sustainable use of resources as opposed to the consumerist attitudes of the urban dwellers. Moreover, the artifact in question allows for tracing the history of the city from the point where it only started developing to the present days, when it has become a large and technologically advanced community.

A graffiti image on the wall of one of the Bellevue buildings (Bennett para. 1)

The significance of graffiti as an art form may be doubted, yet the very phenomenon will never go away. Whether it is a fierce protest against the social and cultural norms or a naively blatant manifestation of one’s artistic abilities, graffiti will always be a part of the urban artifacts treasure trove. The opportunities that graffiti opens in terms of rendering a specific idea are truly ample, which makes the subject matter one of the most powerful, though often administratively punishable, elements of the urban culture.

The graffiti depicted above was drawn under 405 North overpass roughly in 2008. It has a very peculiar structure, with the elements of various nature and colors of different intensity intertwined in a single artwork. The floral patterns that can be noticed in the center and the upper left corner of the picture display the tendency to rejuvenate the sustainability concept popular in the 2000s.

A picture from the Bellevue Festival of the Art (“Bellevue Festival of the Arts” para. 2)

The first page of the booklet for the Bellevue Festival of the Arts is a graphic example of the key urban concepts of industry and progress mix with the ones that represent nature. Thus, rather witty commentary on the need for urban sustainability is represented. The choice of colors also hints at the significance of the nature-vs.-nurture conflict in the present-day urban setting.

The designing choices made to create the image on the left side of the picture send a very clear message to the audience, hinting at the need to establish a deeper connection between nature and the city. The artifact, therefore, can be viewed as an attempt for reconciliation between the proponents of urbanization and those supporting the return to nature.

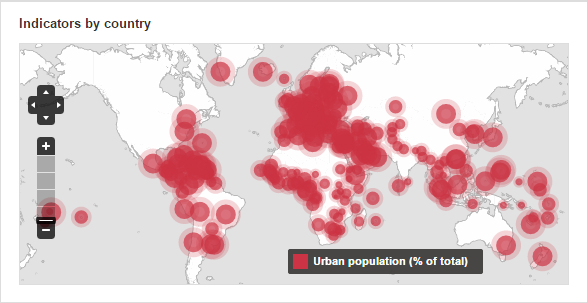

Urbanization rates in 2013 (“Urban Development” para. 2)

The statistical data provided above shows the increasing pace of the city urbanization process in a rather graphic way. As the information offered in the graph below displays, there is an obvious tendency for cities all over the world to develop technologically, which can be viewed as a rather positive change. The lack of emphasis on the effects that this technological progress has on the environment and the use of exhaustible resources, however, are beyond deplorable.

According to the graph, the urbanization process has swept even small towns are nowadays striving to develop into urban areas. Consequently, the emphasis on sustainability as the key to reasonable use of the city resources has become quite tangible in the urban area. The statistical data provided above represents both the threats and opportunities of the increasingly strong emphasis on technology and industry as opposed to agriculture.

A poem concerning the farmers market (“Bellevue Farmers Market Schenectady” para. 1)

Though the city background with the silhouettes of down-to-earth office buildings can hardly spark any poetic thought, poems devoted to cities and their inhabitants exist; moreover, these poems take a special niche in the realm of urban literature. As a rule, these poems are related to a certain hot-button social, economic, or political issue and have a comparatively short shelf life, becoming long-forgotten after the issue in question is resolved.

The poem under analysis can hardly be viewed as an exception; it represents the spirit of commercialism, which every large community in the United States is shot through with. The poem, therefore, while being full, represents the direction in which most cities tend to go nowadays, i.e., the attempt at expanding through the enhancement of their private entrepreneurship sector.

Crossroads Bible Church (Crossroads Bible Church para. 1)

Religion is an admittedly big part of many peoples’ lives, which is why ignoring some of the artifacts of the city that are related to religion is barely possible. Therefore, the church, as an essential element of the urban community development, must be considered as well. The Crossroads Bible Church is one of the places that allow for the spiritual analysis of the progress that the city has made over the years.

While the specified institution cannot technically be viewed as a part of either the urbanization process or the environmental concern, it helps shed some light on human nature and, therefore, understand the problem from both the individualist perspective and the standpoint of the community. The specified institution adds a moral dimension to the problem.

“Promised Land” (Berry para. 1–27)

Being one of the most powerful means of expressing emotions, songs are often devoted to cities as the places where dreams are born and may come true. Chuck Berry’s famous “Promised Land” is no exception to this rule; exploring the idea of another wayward son searching for the Promised Land, where dreams come true, it takes the lead character to the big city.

It helps the audience realize the charm of small towns, such as Norfolk, VA, that used not to be affected by the urbanization process greatly. Though the theme of the song can be considered somewhat corny, the timeless feeling that it renders, as well as its ability to get the charm of a small city across, makes the song a part of the urban classics.

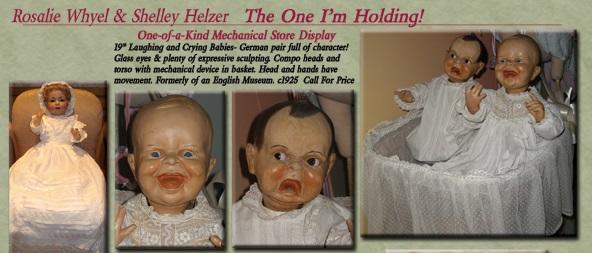

A doll from the Bellevue Museum of Doll Art (Rosalie Whyel Museum of Doll Art 2)

Though dolls are universally considered charming, some of the exhibits of the Rosalie Whyel Museum of Doll Art will inevitably make the audience cringe. Even though the museum was shut down in 2014, the dolls are still available for sale.

The artifacts might not be the kind of toys that loving parents would buy for their children, yet they display the progression of the city’s history in a rather detailed way. For example, the dresses that the figures and dolls wear, help locate the stages in the urbanization process of the city. For example, while some of the dolls feature pastoral designs, others are dressed in the clothes that can be described as the attributes of an average industrial city dweller.

Lacey V. Murrow Memorial Bridge (“A Day in Seattle” para. 1)

Although a bridge cannot be technically defined as an artifact, the Lacey V. Murrow Memorial Bridge falls under the latter category. The reasons for this are that the bridge is not only a technological advance that allowed creating a connection between Seattle and Mercer Island (“A Day in Seattle” para. 2), but also the remnant of the U.S. history. Indeed, the creation of the bridge contributed to the industrialization of the city and its further development.

In other words, by building the artifact in question, the residents of Washington, DC, predetermined the premises for the further urbanization of the city. Magnificent and beautiful, the construction adds an unforgettable touch to the scenery, though clearly defining the boundaries between the artificial world created by the human civilization and the realm of nature.

Artifact Brewery (Steigerwald para. 1–15)

Liquor might not be considered the highlight of the modern art of food production, yet the history of breweries that survived years after they had been founded deserve closer attention. The Jackson Brewery previously located in Northside and recently being moved to a different venue may not be the most valuable artifact, yet is one of the most peculiar ones.

The age of the brewery determines its uniqueness – the artifact dates back to the middle of the 17th century. The evolution of the brewery is nonetheless interesting. The fact that the place used to be a church and a gymnasium may spark some controversies, though. In some way, the progress that the building has undergone can be viewed through the lens of progress as the victory of business over the traditions and values that seem to belong to a different community.

The Car, the Cinema and the Blues Brother (“Hollywood Boulevard” para. 1)

Perhaps, one of the most bizarre and at the same time, unique artifacts, the one created by fans of the classic movie, is also the most memorable. Though the specified artifact does not belong to a different era (in fact, it was built in the second half of the previous century) and does not feature any fantastic art, it is still beyond impressive.

Whereas the artifact in question is not related to the subject matter directly, it displays the significance of one of the most powerful tools for promoting urbanization, which is media. The latter affects people greatly. It shapes their mind frame, helps them transfer information faster, and reinforces progress; therefore, exploring the significance of media of various genres is essential to the analysis of the pace at which present-day urbanization occurs.

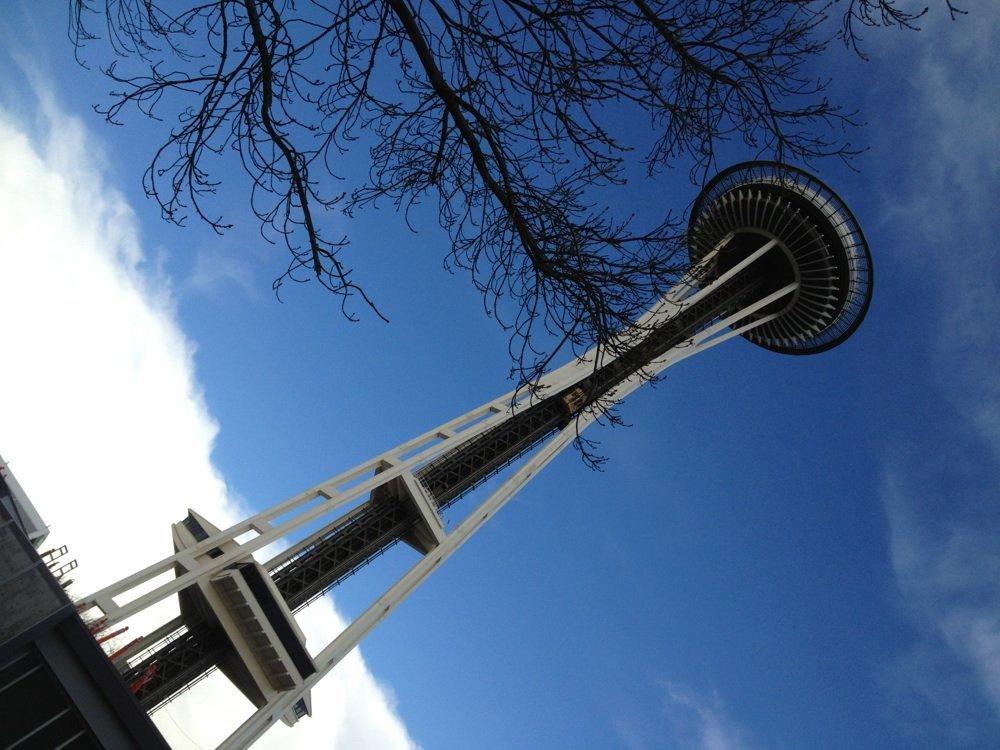

The Space Needle (“Space Needle” para. 1)

Another unique attempt at capturing the charm of the urbanization process, the creation of the so-called Space Needle, triggered an unceasing flow of tourists in Bellevue, WA. Seeing that the architectural artifact is comparatively young, it does not embrace the uniqueness of the city culture, unlike other artifacts.

Instead, it provides an opportunity of taking a glance at the future of the urbanization process. The Space Needle is an interesting metaphor for reaching out to the heights that used to be unattainable several decades prior, yet are part and parcel of the near future.

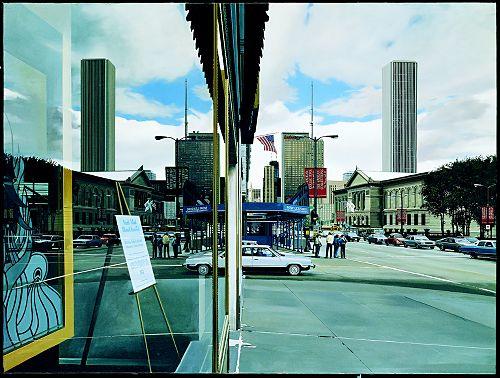

Chicago (“The City as Artifact” para. 1)

One of the fascinating things about artifacts is that their scale often goes entirely out of proportions. While a work of art has certain limitations in terms of size, artifacts often happen to take a rather impressive amount of space. It is not merely a house or a block thereof that is being talked about; the focus of the study concerns an entire city this time.

Chicago is no stranger to tourists and major attention. Here is a tourist attraction basically around every corner of the city. As a result, Chicago is often considered the artifact of the United States (“The City as Artifact” para. 1). Having gone a long way from a small transportation hub to a major city, Chicago includes both the remnants of its past and the references to its modern days.

Urban Forests (UW Botanic Garden News para. 1)

Though the term “artifact” is traditionally applied to the elements of the urban design that have been manufactured, the artificial forest grown in Bellevue, WA, can also be viewed as a specimen of urban artifacts. Created by people, urban forests are supposed to play the role of delicate support for nature in the hostile environment of big cities.

Because the process of urbanization affects biodiversity and the overall natural evolution heavily, the urban artifacts under analysis are of huge essence to the residents of the area. To the concern of the local dwellers, though, urban forests are quite hard to maintain; moreover, the restoration of a completely natural setting is barely possible. Still, the concept of urban forests is one of the few ideas that may work as a tool for restoring the balance between nature and nurture.

Lake Washington (“Photo of Mt. Rainier and Lake Washington”) para. 1

Much like urban forests, urban lakes fall under the category of artifacts, as they are created by people, and Lake Washington is one of those. The lake represents an endeavor of restoring the balance between the rapid urbanization process and the need for sustainability. Despite being artificial and suffering several instances of industrial pollution, the lake has improved local ecology impressively.

“Bunny Man” (“The Legend of the Bunny Man” para. 1)

Talking about urban artifacts is impossible without touching upon urban folklore. Though the creepy story of Bunny Man originates from Virginia, it has spread quickly across the Washington, DC area and is still used as a local horror story. The myth about the Bunny Man shows that, while being technologically advanced, city residents may succumb to a common fear of the supernatural.

The Mysterious Disappearance of the Letter “J” (“No Way, No Jay” para. 1)

Rumors say that there is no street name starting with “J” in entire Washington, DC, since Pierre L’Enfant, the architect, was at odds with the local chief justice, John Jay. However, a closer look at the records of the city will reveal that the story has nothing to do with the truth. Nevertheless, tourists still flock to the area, threatening the sustainability of the district.

Bellevue Downtown Park (“Bellevue Downtown Park” para. 1)

Placed in the heart of the city’s downtown, the park serves its purpose of providing residents and tourists with an opportunity of having some rest. The park can be viewed as the perfect response to the urbanization concern, which has been brewing in Washington, DC, for decades. A solution to a range of environmental issues, the park is a major step in the right direction.

Bellevue’s Downtown War Memorial (“Bellevue’s Downtown War Memorial” para. 1)

Despite being an artifact in itself, the Bellevue’s Downtown Park has a range of artistic elements to offer to its viewers, and the Bellevue’s Downtown War Memorial is one of them. Honoring the memory of the people, who died in battles for the greater justice, and promoting their qualities to the present-day dwellers of the city, the monument links the past of Washington and its future, therefore, teaching an essential lesson about the significance of fending for one’s rights.

Wilburton Hill Park (“Wilburton Hill Park” para. 1)

The image of a tree stump, which has been stubbed out of its natural environment, is a far more obvious, in-your-face message concerning the need for sustainability in the city than any other artifact that has ever been produced. While the message could have been delivered in a much more subtle way, it is still quite impressive and serves its purpose.

Unfortunately, while it was designed to be the big wakeup call, it is viewed nowadays merely as an original representation of a rather worn-out idea. Nevertheless, as an urban artifact, it works perfectly and conveys the key message concerning the need to preserve the environment in a very efficient manner.

Artifacts and Their Significance

The phenomenon of urbanization is traditionally viewed as a positive one, which is quite understandable – urbanization promoted further progress, making it possible for numerous industries to evolve, not to mention the fact that it encourages companies to expand and, therefore, creates new job opportunities.

However, the cost that urbanization comes at is not to be forgotten, either; because of the emphasis on the economic and financial benefit that follows the urbanization process and the subsequent lack of concern for the environment, the latter suffers greatly.

The environmental concern has been raised several times, with enthusiasm concerning the improvement of the situation gradually fading away. Because of their ability to incorporate personal and social issues, numerous city artifacts embrace the variety of ideas regarding the problem, a range of the artifacts in question suggesting rather unusual solutions.

As it is rather easy to spot, the artifacts described above, though very diverse, concern the process of urbanization and the transfer from the agricultural stage to the urbanized one. Claiming that technological progress should not be encouraged would be hardly reasonable; indeed, it is the promotion of IT that helps improve the functioning of a range of services, therefore, making people’s lives better all over the world.

However, people seem to disregard the fact that continuous urbanization without a thorough analysis of the consequences comes at a price. Unless a sustainable path for city development and the urbanization of the nearby areas is introduced, the people living in these areas may face a serious crisis concerning the lack of natural resources and biodiversity.

Much to the credit of the people living in the areas that are subjected to rapid changes and evolve from agricultural to urban ones, they attempt at making the progression not as rapid and challenging to nature as it might be. Claiming that people fail to understand the adverse effects of urbanization would be unfair to the progress of the civilization; more to the point, there have been numerous attempts at raising awareness regarding the issue, as well as shed some light on the subject matter, artifacts being only a part of the campaign.

It can be assumed that people are trying to locate the solution that will allow for each party of the conflict to benefit, which numerous artifacts mentioned above display rather graphically. The specimens of street art described above, perhaps, are the most sincere, though not the most elaborate, examples of a gradual realization of the problem.

The graffiti artworks discussed above may seemingly contain little to no sense, as they are most likely to have little to no connection with the setting in which they have been painted. Being the brainchild of an unknown author, the artifact contains the themes and references that a side viewer will fail to guess. Nevertheless, one can track down the ideas that have influenced the author rather clearly.

First and most obvious, floral patterns hint at the tendency to incorporate the elements of a pastoral in the artwork. Herein the reference to the nature-vs.-nurture theme lies; whether consciously or not, the creator of the graffiti under analysis tries to reference the notorious environmental conflict.

Even the artifacts that do not seem to suggest a reasonable solution to the problem of cities expansion at the cost of biodiversity and natural resources abuse, some elements of the design still hint at the possibility of a change. For example, the bridge mentioned above (i.e., the Lacey V. Murrow Memorial Bridge) can be considered a metaphor in itself, i.e., a reminder about the possibility of establishing a connection between nature and the civilization.

The subtle touches that certain design choices add to the development of the problem-solution cannot but be appreciated. It should be noted, though, that the metaphorical environmental significance, which the bridge in question bears, cannot possibly match the negative effects, which it has had on the environment of the area. Specifically, the fact that its creation has disrupted the ocean flora and fauna deserve to be mentioned.

Nevertheless, some elements of the urban design can be viewed as a major compromise between the need to evolve and the necessity to retain the connection to nature. The picture from the Bellevue Festival of the Arts (“Bellevue Festival of the Arts” para. 1) can be considered one of the most subtle endeavors at pointing at the obvious significance of the sustainability policy. It is quite remarkable that, unlike other artworks carrying a similar message, the bulletin from the Bellevue Festival of the Art is entirely deprived of any obnoxiously obvious messages showing the dread of the refusal to sustain nature.

Instead of portraying the supposedly terrible outcomes of people’s unwillingness to reconcile with nature and accept the idea of sustainable use, the bulletin shows that people are, in fact, an integral part of nature. This idea has much more dignity and worth to it, as it credits the viewers of the artifact as being intelligent enough to understand a specific message without being scared into believing it.

The last, but not the least, the sculpture of a stump that has been taken out of the ground, deserves to be mentioned among the most powerful artifacts that serve their purpose in conveying the necessity to shift to the more sustainable use of natural resources and to make the process of industrialization less painful.

While admittedly less subtle than the picture from the Bellevue Festival of the Arts announcement, the given artifact can be deemed as essential due to its expressivity. Unlike the rest of the artifacts mentioned previously, it makes people think.

The thought-provoking artwork was intended to have no double meaning; otherwise, it would have been viewed as another elegant argument in favor of sustainability and, therefore, would have failed as a piece of art.

Although the artifact does not serve as the warning of a specific danger that the unrestrained process of urbanization will lead to, it still carries enough weight to impress the viewers and convey the intended message clearly and concisely. A perfect example of form following the function and enhancing expressivity, the given artifact has an exemplary impact on the audience.

One could argue that the Crossroads Bible Church should have been viewed as the focus of the analysis and the most significant element of the list. Indeed, apart from containing a range of artifacts that are both spiritual and essential to the evolution of human culture, the Church itself is, in fact, a large artifact that serves to prove the connection between the present-day society that is concerned with the evolution of technology, and the society of the past, which viewed the nature as a part and parcel of the divine and, therefore, having a special place for nature in its set of values.

Therefore, though it might be considered a rather far stretch, the Crossroads Bible Church, incorporates the elements that belong to both the modern, technologically advanced era and the society that considered the connection to nature the top priority. Therefore, the specified artifact – or, to be more specific, the collection of artifacts – can be considered the symbolic representation of the opportunities for people to locate the compromise between the urbanization process and the environmental policies.

Each of the elements mentioned above, therefore, represents a step in the process of urbanization. One must not delude oneself by thinking that urbanization is something to be avoided, though; as most of the artifacts listed above show, the process is the graphic representation of the progress that the civilization has made so far. More importantly, the artifacts listed above display the complex path of understanding the relationships between civilization and nature.

The timid attempts at copying nature and its creations were replaced with the endeavors of building something even more grandeur, and finally approached the rejection of the harmonic principles suggested by nature.

However, as soon as the urbanization process took its toll and the environmental concern appeared on the agenda of the global community, urban artifacts started reflecting the related concerns, rendering the timeless nature-vs.-nurture conflict. At present, some of the artifacts hint at the possibility of the conflict resolution. Yet, the vagueness of these solutions shows that more time and effort must be put into addressing the issue.

Works Cited

“A Day in Seattle.” Pinterest. 2014. Web.

“Bellevue Downtown Park.” Flickr. 2014. Web.

“Bellevue’s Downtown War Memorial.” SeattlePi. 2011. Web.

“Bellevue Festival of the Arts.” Bellevue Fest. 2014. Web.

“Bellevue Farmers Market Schenectady.” Facebook. 2014. Web.

“Bellevue History.” Fastside Heritage Center. 2015. Web.

Bennett, Scott. “Graffitied Wall.” Flickr. 2008. Web.

Berry, Chuck. “Promised Land.” Metrolyrics. 2015. Web.

“Crossroads Bible Church.” Yelp. 2015. Web.

“Hollywood Boulevard.” Tripadvisor. 2015. Web.

“No Way, No Jay.” Snopes.com. 2015. Web.

“Photo of Mt. Rainier and Lake Washington.” Panramio.com. 2015. Web.

Rosalie Whyel Museum of Doll Art. “The Museum Store.” Rosalie Whyel Museum of Doll Art. 2014. Web.

“Space Needle.” Yelp. 2015. Web.

Steigerwald, Shauna. “Urban Artifact Brewery Moving forward in Northside.” Cincinnati, 2015. Web.

“The City as Artifact.” The Encyclopedia of Chicago. 2015. Web.

“The Legend of the Bunny Man.” WETA. 2015. Web.

“Urban Development.” The World Bank. 2013. Web.

UW Botanic Garden News. “Up By Roots: Healthy Soils and Trees in the Built Environment.” UW Botanic Garden News. 2014. Web.

“Wilburton Hill Park.” Virtual Tourist. 2011. Web.