Abstract

This report is a usability test and PACT analysis of a Call Center Traffic Management System tool. The usability test of the tool is conducted for the three out of ten usability principles defined by Jakob Nielsen: visibility of system status, user control, and freedom, aesthetic and minimalist design. These principles are applied to the graphical user interface and the dashboard reports of the tool. The usability methods Heuristic Evaluation and Survey are used for the usability test.

The PACT analysis is conducted to find the utility of the tool in the optimum resource management at a call center. The resources that were considered are the call center telephone agents and telephone line for the inbound calls. The methods used for PACT analysis are brainstorming with the staff of the call center, the author’s own cognitive knowledge, tool documentation, and internet research.

The observations and interpretations of the test and analysis are presented in the report.

Introduction: Scenario

A call center caters to the customer support requirements of multiple organizations. Multiple organizations are supported in a single call center by connecting the toll free number lines (0-800-number) of business client companies to the call center telephone board. When a call arrives on a particular line it is forwarded to the call center floor that is serving that particular business line. A telephone agent on the floor answers the call; before the agent answers the call a welcome message to be used by the agent to greet the caller is displayed on the agent’s computer screen. This agent will then use the business client information database available to the call center to process the customer query. Customer satisfaction with the most optimum call center resource usage is the objective of the call center and the business client. Following processes are involved in the processing of a customer call at the call center:

- Call Queuing – This process queues the incoming calls. The following statistics is calculated in order to ensure the optimum use of call center resources: call arrival time at the back of queue, call waiting time in the queue and call service time at the front of queue. The last of the three parameters is recorded to observe if the customer abandoned before the call was serviced (Queuing Theory).

- Call Service & Quality Control– After the call has landed on an agent’s service desk the agent will identify the customer by the caller ID, input Personal Identification Number (PIN) or other information provided by the customer. The call has landed on the call center agent’s desk because the customer query was not answered by the automated Interactive Voice Response (IVR) system. Hence the quality of service provided by the telephone agent to the customer is monitored. The agent must be able to answer accurately, clearly and quickly to all customer queries. The parameters that are measured by the monitoring tool are: average speed to answer the call, average call duration, call wrap-up time and call query parameters about the purpose of the call.

- Call Center Staffing & Scheduling – Center staffing process anticipates call volume to avoid over-staffing or under-staffing. Information required is call volume forecast, actual call volume, type of calls and staff (full-time, part-time, contract, seasonal). The parameters measured are: number of agents logged in, number of agents available to take calls, number of calls, call time (including call duration & wrap-up).

The usefulness of the Call Center Traffic Monitoring System (CCTMS) is to be measured by analyzing its usability and utility. The usability of the CCTMS is to be measured from the perspective of the call center management staff, i.e. the ease of use of the user interfaces provided by the CCTMS for the configuration of various parameters. The utility of the CCTMS is to be measured for the effectiveness of the CCTMS system in efficient resource optimization for the call center. The PACT analysis of the CCTMS system is conducted to determine the usefulness of the CCTMS system in providing better service to the business client serviced by the call center and the customers of the business client.

Methodology

Usability

The usability testing of the CCTMS was conducted for the following usability principles (Nielsen 2005):

- Visibility of system status – Does CCTMS dashboard provide required information in the objective manner? The CCTMS dashboard must be updated regularly to inform the call center management about the status of queued calls and the telephone agents on desk.

- User control and freedom – The CCTMS user input interface robustness was tested in case wrong parameter values are entered. The system must support parameter range checks and must have a provision to allow the administrator to return to the previous state in case of error.

- Aesthetic and minimalist design – The design of the CCTMS must ensure that extra parameters are not included in the input dialogs or displayed in the output reports. Extra input parameters or output information creates unnecessary confusion and diminishes the information value.

The usability methods used for usability testing of CCTMS are (Hom):

- Heuristic Evaluation – The author of this report conducted heuristic evaluation of CCTMS by studying the dashboard reports and manipulating parameters to determine the impact on call center efficiency and applicability of the usability principles listed above.

- Survey – A telephonic survey of business client customers was conducted to determine the effectiveness of staff scheduling performed based on the CCTMS reports. A survey was also presented to the call center telephone agents to determine the influence of the staff scheduling changes.

Heuristic Evaluation

Following tests were conducted on the CCTMS to determine the usability of the system:

- The dashboard report information was studied.

- The frequency of the dashboard report updates was noted.

- The user interface to input parameter values was tested for valid and invalid combination of parameter values.

- The input parameters required in the call center traffic & staffing calculator were identified.

Survey

Following questions were asked in the telephonic interview of the business client customers:

- Did you have to abandon your call due to no-answer? This question was asked to the frequent callers to determine if they had to wait for a very long time in the call queue and had to abandon the call due to no-answer from the telephone agent.

- Did you have to redial or postpone the call due to line busy signal? This question was asked to the randomly selected customers to determine if the number of telephone lines were sufficient.

Following questions were asked to the call center staff:

- Are you receiving more customer calls after rescheduling of staff? This question was asked to determine if the telephone agent was answering more number of customer calls after the staff in the call center was reduced. The idle time between calls must have reduced.

- Do you notice improvement in call center staff scheduling based on CCTMS reports? This question was asked to the call center management to determine if the CCTMS reports were useful and staffs overload or under-load is avoided.

PACT Analysis

The PACT analysis of the CCTMS was conducted to determine the affects of this system on the functioning of the call center, work life of the telephone agents and service to the business client customers.

- People – Who are the people who will use the CCTMS? For what purpose will these people use the CCTMS?

- Activity– What activities can be performed by CCTMS?

- Context – In what context CCTMS can be used? The contexts considered were: physical, social and business.

- Technology – What technologies are used by CCTMS?

PACT analysis of CCTMS

People – CCTMS is a management tool that will be used by the management of the call center. The CCTMS system records the call center traffic parameter values and then present dashboard reports about the staffing status to the management. The dashboard reports are used by the management to observe the call traffic, staff overload or under-load conditions and to deal with call congestion. PACT analysis is conducted to determine if the CCTMS reports are effectively used by the management.

Activity – CCTMS records call traffic parameters at all times and presents dashboard reports at regular intervals as configured. The results that are displayed in the reports are comparative analysis of the default values configured and the traffic parameter values recorded in a given pre-configured duration. The traffic parameters recorded are:

- Average number of calls received in an hour

- Average number of calls answered in an hour

- Total number of telephone agents on duty

- Average call duration

- Average call wrap-up time

Based on this study the action is taken to reduce or increase the call center resources: agents & telephone lines. PACT analysis was conducted to determine if these features of CCTMS tool were sufficient for efficient administration of the call center.

Context – CCTMS is used by the call centers that provide customer support service to one or more business companies. Business companies may be located at distant places and in different continents. The business client toll-free number line is connected to the call center through a leased line or SIP. The business client information database is provided to the call center through online connection on the internet or offline database storage is provided.

Physical context – PACT analysis in physical context is done to determine if the staffing & scheduling reports provided by the CCTMS tool inflict physical pressure on the telephone agents.

Social context – PACT analysis in social context is done to determine if the staffing & scheduling is being done according to the day of week and time zone of the business client.

Business context – PACT analysis in business context is done to determine if the business client requirement of the number of telephone agents and lines is the most optimum use of call center resources. It is possible that the business client requirement for average queuing time is low/high thus affecting the resource utilization.

Technology – The call center is equipped with sufficient hardware and software resources to allow smooth functioning. The PACT analysis is conducted to determine if the software and hardware tools used to run CCTMS are the best solutions.

Software – Computer Telephony Integration (CTI) enables collection of call queue and call service statistics for effective staffing and scheduling analysis. CCTMS integrates with CTI to generate status reports for the dashboard. CCTMS client must run on the management staff workstations in order to receive the dashboard updates.

Hardware – The call center is connected to a PSTN trunk to receive telephone calls and for broadband internet connection. PSTN and VOIP calls are received by the call center. All calls are managed by the CTI software that runs on a Windows/Linux servers. CCTMS is a front-end application that integrates to CTI database and may run on the same or different server.

Observations

Heuristic Analysis

The CCTMS tool provides a traffic calculator to determine the number of call agents and telephone lines required (Westbay Enginers Limited).

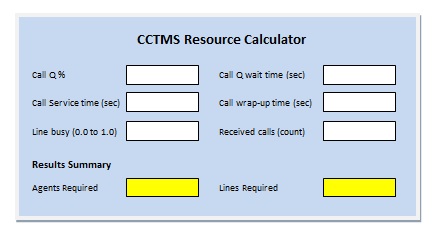

CCTMS calculator for staff & telephone lines requirement

The input parameters for the CCTMS tool calculator are:

- Call queue ratio – The ratio of calls that can be queued.

- Call queue wait time – Average Q wait time for a call.

- Call service time – Average time spent by the agent on servicing the customer.

- Call wrap-up time – Average time spent by the agent in administrative wrap-up after customer ends the call.

- Line busy ratio – The ratio for the number of calls that are allowed to fail because the customer found toll-free line busy.

- Calls received – Number of calls received in an hour.

Based on these input parameters the number of agents and telephone lines required were calculated by the tool to meet the parameters 1, 2 and 5.

An upper and lower bound for the parameters 1, 2, 4 and 5 was set in the system and could be modified with administrator access permissions only.

Dash board reports were updated at the end of every hour and a peak hour report for the day was presented at the end of day. From the CCTMS documentation it was found that these hourly statistics records were updated in the database and could be displayed through the tool GUI. A comparative report as shown in the graph was updated on the CCTMS dashboard every hour.

Resource Utilization Chart

From this sample chart it is observed that more number of calls are being received and this has increased the number of calls queued and the queue time. Even if the average duration of a call is low more number of customers is denied service due to line busy. For efficient service as promised to the business client the number of agents must be increased. The call center management can take immediate action by putting temporary staff (rotation staff) on duty.

The configuration interface of CCTMS had the input parameters 1 to 5, these parameters were the threshold values defined for the call center traffic management. These threshold values were used as bench-marks for comparative data analysis in the reports.

Survey

Based on the traffic data that was collected for a period of month the survey questions were asked to ten customers.

- The ten customers were selected from the callers who had called in peak hours when Q wait time was high and had called again after the corrective measures were taken. Only two out of ten customers had abandoned the call due to long Q wait time. These two customers could quickly talk to the call center telephone agent when they called again. It was concluded that the corrective measures were effective since the two customers had made the repeat call on the same week day in the same hour.

- Ten random customers were selected based on the feedback received from the business client that the customer support of the business client was short of resources. These were the customers who had called at the peak hours after corrective measures were taken. Seven of these customers could not make to the call Q before the number of telephone lines was increased.

It was observed that there was a business requirement of these ten customers to seek customer support from the business client serviced by the call center on this week day and hour of the day.

The call center staff that worked during under-load hours was asked the questions listed in section 2.

- The answer of all the telephone agents was affirmative and this was confirmed based on traffic data. The agents did not complain about physical strain or work overload.

- The management staff commented that CCTMS reports were very useful and the over staffing was effectively handled. The extra staff during under-load hours was assigned other duties.

Interpretation

The PACT analysis of CCTMS identified the following strengths in the call center traffic monitoring, staffing and scheduling software automated tool:

- The tool presented hourly updates of the call center resource status. These reports were used to resolve overload and under-load conditions of the resources.

- The tool had an in-built calculator to calculate the telephone agents and telephone line requirements for the given traffic parameters.

- The tool had provision for configuring threshold values of traffic parameters. This enabled configuration of exception report generation when the threshold is breached. This feature helps avoid degradation of service by ensuring immediate action.

The following feature weaknesses were observed in the CCTMS tool:

The tool was SQL based and required CCTMS client configuration on the management desktop workstation. This limited the remote access feature, the client was required to connect to the CCTMS server through internet.

The CTI software that provided inputs for the CCTMS tools recorded traffic data for every call. Therefore the traffic information for every telephone agent was available. It was observed that some agents were slow in processing the customer request and hence the call service time was often exceeding the threshold value defined for a particular service type call. Due to this the call Q ratio was breached and the queue waiting time also exceeded the threshold value. This ripple effect degraded call center performance. There was no interface in CCTMS to observe performance of a defaulting agent so as to consider a replacement before end of the day when detailed analysis of traffic data was studied.

Suggested Improvements

The following improvements are suggested to enhance the features of the CCTMS tool.

- The SQL based database can be translated to an XML based system.

- New features such as online connectivity without the need to install CCTMS client can be added to enhance the mobility of the management staff.

- XML based system can use RSS feature to inform traffic parameter breach and provide dashboard reports.

- A CCTMS client for the telephone agents can be built that will assist them in improving their performance. The client will include the following counters that will count-down to zero value from the default value for every call:

- service time for the call

- wrap-up time for the call

The counter will go RED when it becomes zero and then counts upward to indicate time overflow. A CCTMS report will be generated when any of these counters goes RED. LabVIEW software can be used to build this counter dialogue.

Conclusion

The usability test for the Call Center Traffic Management System tool has been conducted for the three usability principles listed in section 2 of this report. It is observed that the tool provides sufficient status information for the management to be able to take corrective decisions when necessary. The tool user interface is easy to use and provides online help & documentation that explains the features. The exception report generation feature enhances the usefulness of the system.

The PACT analysis of the CCTMS system was conducted and it is observed that a new CCTMS client feature can be added for telephone agents in order to monitor their performance. The PACT analysis results informed the author about how the resources are reassigned for optimum performance in the peak hours dependent on the time zone of the business client. It is also observed that technology enhancement to the tool will enable addition of new features to the system. The SQL based system can be transitioned to an XML system.

The usability test and PACT analysis exercise was very successful. The author learned various traffic data interfaces of the call center software. The application of the usability principles was a learning exercise to know how software interactive systems are designed. The survey questionnaire provided an opportunity to know how outbound survey calls are made and was a practical exercise of interacting with customers. While heuristic evaluation was an exercise to learn the tool and collect observations for the report it is concluded that survey was a more enjoyable part of the project. The PACT analysis informed the author about the management and an agent relationship and how traffic data is used to control the duties.

In the end author has listed the strengths and weaknesses of the CCTMS system. Some suggestions for improvement of the tool have been included in the report. Author would like to thank call center agents for their time in assisting the conduct of survey and discussions for the suggested improvements.

References

Avaya. March 2007. The path to intelligent communications. Web.

Brown, D. Lawrence., 2003. Empirical analysis of call center traffic. Web.

Guide to the Harvard System of Referencing.2007. University Library. Angila Ruskin University. Web.

Hom James. The Usability Methods Toolbox. Web.

Huawei. Call Center. Web.

Nielsen, Jakob., 2005. Ten Usability Heuristics. Web.

PACT Analysis. Web.

UK toll free numbers. Web.

Westbay Engineers Limited. Call Center Calculator (Ansapoint). Web.

Wikipedia. Call Centre. Web.

Wikipedia. Queuing theory. Web.