Abstract

Israel has experienced an influx of immigrants for over a century. Largely informed by Zionism, many Jews from around the world have integrated with the local population in Israel and made the country their home. However, this process has been difficult because of several perceptual issues about immigrants that plague Israeli society. Negative public perceptions about immigrants in Israel highlight a common challenge that most immigrants face when assimilating to the Israeli society. Observers position the role of the media at the center of this debate by highlighting its role in propagating the negative perceptions of immigrants in Israel. Historically, many researchers have investigated these issues from an outward-in approach, by exploring the influence of the media in shaping public perceptions. However, this paper adopts the reverse approach by conducting an inward-out analysis of the perceptions of immigrants regarding media coverage of their issues.

After sampling the views of 15 immigrants from western European, Eastern European, and African backgrounds, this paper establishes that most immigrants living in Israel believe the media misrepresents them by stereotyping them negatively. Evidence also shows that the media does not understand the immigrant way of life, thereby creating a deep sense of dissatisfaction among immigrants, concerning how they represent immigrant issues. This study also negates the notion that immigrant groups perceive one another negatively along ethnic lines. Instead, empirical evidence shows that common plights and misrepresentations about immigrants in the media unite them. Interestingly, despite the negative coverage of immigrants in Israeli media, this paper shows that a large section of immigrants still prefers to consume Israeli media, as opposed to their local media.

Introduction

Aliyah denotes the mass migration of Jews from other parts of the world to Israel. This concept largely symbolizes a key pillar of Zionism (nationalism of the Jews and the Jewish culture) (Wendehorst, 2011). Historically, many Jews, around the world, consider immigration to Israel as an important part of their life because it symbolizes their return to the “holy land.” Historical excerpts show that some of the earliest forms of immigration into Israel started in the 1800s and since Israel emerged as a nation-state, more than 3,000,000 Jews from around the world have found a home in Israel (Gavish, 2010). From the onset of the Aliyah movement, many immigrants in Israel have therefore gained permanent residence in Israel. Although, some of them are undocumented and still live in Israel, unfavorable religious and political environments in their home countries have made it difficult for the Israeli authorities to deport them.

From the growing waves of immigrant settlements in Israel, public perceptions have changed regarding the status of immigrants in the Middle East nation (Kushnirovich, 2010). Neuman & Oaxaca (2005) say this issue has also created divisions within the Israeli society regarding the treatment of immigrants in Israel (mostly, undocumented immigrants). For example, some people do not see immigrants as different citizens from native Israelis, while others see them as threats to Israeli security and stability (Neuman & Oaxaca, 2005). From the same divisions, some people have held demonstrations in key Israeli cities to petition the government to address the immigrant issue, while others have been neutral towards the same. The law of return has commonly surfaced in this debate, as it eases the ability of immigrants to get Israeli citizenship, so long as they are Jews (Wendehorst, 2011). Legally, this provision has elevated issues of Jewish immigration to Israel as a national issue (at the center of the politics of immigration are the ideologies of Zionism, which have greatly helped to shape public perceptions about immigrants in Israel – the relationships between Palestine and Israel affirm this fact).

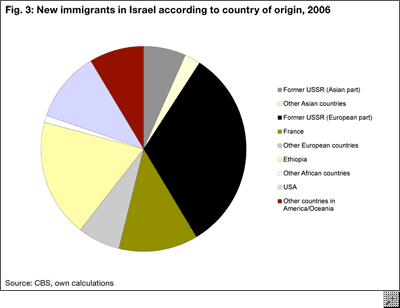

A key institution that has shaped the diverse ideologies regarding immigrants in Israel in the media. Security, jobs, and congestion are only some issues that the media has used to evaluate the state of immigrants in Israel (Neuman & Oaxaca, 2005). Historically, many cinematic representations of Israeli politics have not shied away from delving into the intrigues surrounding immigrants in Israel. Israel has different groups of immigrants. Broadly, the main immigrant groups in Israel include African immigrants, US and Western European immigrants, and Eastern European immigrants (Nonna, 2008). The diagram below shows the composition of these groups in Israel

According to the diagram above, many immigrants living in Israel come from Europe (mainly the former USSR). A large percentage of this population also comes from Western Europe, Africa, and other parts of the world. Some media reports and researchers believe that these immigrant groups do not receive the same treatment in Israel (University of Haifa, 2010; Neuman & Oaxaca, 2005). Some people also believe the public depictions of immigrants are different for all the three groups discussed above. Relative to this assertion, observers fault the Israeli media for portraying some groups of immigrants favorably, while stereotyping others (media bias). For example, the University of Haifa (2010) says the media portrays immigrants from Western Europe better than it portrays African immigrants. Other researchers say the media portrays Eastern European immigrants better than it portrays African immigrants. Most researchers have however shown a deeper bias between the media’s portrayal of African and European immigrants (University of Haifa, 2010; Neuman & Oaxaca, 2005). Although this paper explores some of these biases in the literature review section of this paper, it seeks to find out the authenticity of these arguments by conducting an empirical study to evaluate the intricacies surrounding the coverage of immigrants in Israel.

Research Questions

This paper conveys a special interest in understanding how Israeli immigrants feel the media portrays them. Key areas of interest that this paper seeks to explore are the feelings of the immigrants regarding if the media stereotypes them negatively, or not, and if they feel the Israeli society is welcoming to them. These questions outline the research aim of this paper

Research Aim

To understand how immigrants in Israel feel they are portrayed in the media.

The main research goals are:

- To establish if immigrants feel satisfied with the representation of immigrants in the Israeli media.

- To find out if the portrayal of immigrants in the Israeli media is accurate or stereotypical.

- To investigate if immigrants in Israel consume Israeli media or media from their countries of origin.

- To find out if there is a relationship between the media contents consumed by immigrants in Israel and their experiences as immigrants in Israel.

Structure of the Paper

Five chapters outline the structure of this paper. The first chapter contains the introduction section. This chapter outlines the research background and the issues that outline the paper. The second chapter outlines the literature review section. This section contains information regarding previous studies that have explored media perceptions of immigrants, not only in Israel but also in other countries that experience immigrant issues. A description of how the researchers conducted the study appears in the third chapter of this paper – the methodology section. The fourth chapter outlines a review of the results emerging from the empirical study (according to the outline of the research questions). Finally, the last section of this paper contains an analysis and conclusion of the study. This section highlights the main findings of the paper and recommends areas for future research.

Literature Review

The Zionist movement saw the first wave of immigrants settle in Israel in the first half of the 20th century (Rebacz, 2010). The immigrants mainly came from Europe. Rebacz (2010)says, in the 1940s and 1950s, the second wave of immigrants came to Israel from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region (most of the immigrants were Mizrahi Jews). The establishment of Israel as a nation-state and increased hostilities against Christians in the MENA region primarily motivated their move to Israel. The first wave of immigrants welcomed most of the Middle East immigrants, but after a while, the society started to treat the second wave of immigrants as the Ashkenazi minority (the Mizrahi and Ashkenazi minority have always disagreed over many issues) (University of Haifa, 2010). These opposing groups have had unresolved issues for decades. After the second wave of immigration, the third wave of immigrants came from Russia in the 1990s (this wave of immigrants was bigger than the previous two). About 900,000 Russians found a new home in Israel during this time (Rebacz, 2010). Former Soviet Union immigrants now constitute the largest population of immigrants in Israel, but immigrants from Africa and Western Europe also comprise a significant percentage of this population.

From the different categories of immigrants in Israel, each group of people developed new lifestyles that resonated (partly) with the host society and (partly) with their home countries. Culturally, many of the immigrants maintained their identity. This process led to the categorization of the immigrant population across cultural and ethnic lines. Some researchers identify this gap as a valid reason for the varying treatment and representation of different immigrant groups in the media. The analysis below explores this issue further.

Media Portrayal of Immigrants and the Roles of Cultural Gaps

The University of Haifa (2010) argues that cultural differences have a huge role to play in describing how the Israeli media perceives different groups of immigrants. A positive media portrayal is often synonymous with cultural discourses that use the Israeli culture as a focal point for comparison (University of Haifa, 2010). For example, immigrant groups that are culturally remote to Israel receive negative media portrayal, while cultural groups that are culturally close to Israel receive a favorable perception. Rebacz (2010) is however pragmatic in how she explains this phenomenon because she says immigrant groups that are culturally remote from Israel tend to receive less cultural support when they stay in Israel. However, immigrant groups that are more culturally inclined to Israel tend to be better accepted and welcomed to the Israeli social, political, and economic space. The media also portrays them more positively than other immigrant groups (Rebacz, 2010). Usually, when such immigrant groups experience segregation, the media perceives this act as a threat (University of Haifa, 2010).

The University of Haifa (2010) conducted a study to investigate the perceptions of immigrants on Israeli media by evaluating more than 7,000 quality newspapers. It affirmed the above findings by reporting that the main difference between the portrayals of immigrant groups was their cultural distance/closeness to the Israeli culture. In detail, the University of Haifa (2010) conducted this study by focusing on two groups of immigrants – soviet immigrants and Ethiopian immigrants. It said,

“While the percentages of articles on cultural integration and segregation are similar for both groups, the main difference is found in the articles relating to cultural disparity. About 7.2% of the articles on Ethiopian immigrants and culture related to the differences between their culture and Israeli culture, while 2.6% of such articles were on Soviet immigrants” (University of Haifa, 2010, p. 2).

The underlying message in the above analysis aimed to highlight the ability of Ethiopian immigrants to integrate effectively into the Israeli society. Some of the main findings that emerged from this analysis were the incompetence of immigrants to use new technology and their inability to adapt easily to urban lifestyles. For example, the University of Haifa (2010) said, most native Israelis often expressed surprise when they encountered immigrants who understood how to use technological gadgets. In further reference to Ethiopian immigrants, the University of Haifa (2010) said that when Israelis responded to questions that investigated their views of how Ethiopians use technology, they often commended the immigrants for learning how to use technology, but still said the immigrants were oblivious about the workings and dangers of technology.

Interestingly, the University of Haifa (2010) also said that an analysis of soviet immigrants did not bring religious undertones in the perceptions of this immigrant group. For example, an evaluation of 1970-1980 soviet immigrants did not show the influence of religion (association with the Jews) in the portrayal of this immigrant group in the media. However, some sections of the Israeli society tried to include religious undertones in the perception of soviet immigrants (the question of Jewish identity), but their attempts were highly criticized by the media because it was highly conscious of the religious values brought by the immigrant groups (Frenkel & Shenhav, 1997). Ethiopian immigrants also experienced the same religious scrutiny (although some Israelis understood that they shared a common religious foundation with the immigrants, thereby seeing no importance to subject them to such evaluations). An analysis of both immigrant groups (Ethiopians and Soviet immigrants) showed that even though the immigrants shared a common religious background with the Israelis, their Jewish identity was highly probed by the media. The media especially used issues of assimilation and the understanding of Judaism to investigate the religious affiliation of these immigrant groups. Boneh (1991) says that the heightened level of scrutiny of immigrants forced some soviet immigrants to develop a cultural identity that appealed to them. Interestingly, the media criticized this trend and regarded it as a threat to Israeli nationalism.

The above findings show some slight variations in how the Israeli media portray Ethiopian and Soviet Immigrants, but Ross (2010) says the media still stereotypes both groups. In one statement, Ross (2010) claims, “Though Israeli media outlets are friendlier toward immigrants from the former Soviet Union than from Ethiopia, overall they are negative toward both groups” (p. 5). Broadly, an assessment of the portrayal of both groups in the media shows that more than 60% of media reports painted the immigrants in a negative light (Ross, 2010). About 22% of the same reports painted the immigrants in a positive light, while only 18% of these reports were neutral towards the immigrants (Ross, 2010). These varying statistics show a valid relationship between the media and public perceptions. The section below explores this issue further

Relationship between the Media and Public Perceptions of Immigrants

There have been contradictory perceptions regarding the status of immigrants in Israel. A study conducted by the Immigrant absorption ministry showed that the public held differing views regarding the importance and status of immigrants in Israel (University of Haifa, 2010). They conducted the study by evaluating the public’s perception of the importance of immigrants and the relation between immigrant numbers and crime in the country. The paper established that about 70% of the respondents saw immigrants as an important addition to the Israeli society (University of Haifa, 2010). However, about half of the respondents said an increased number of immigrants increased the rate of crime in the country. Nonetheless, this perception proves to be inaccurate because government records show that only 9% of crime suspects in Israel were immigrants (University of Haifa, 2010).

The study also established that the media reinforced most of these views.

Frenkel & Shenhav (1997) did a similar study to investigate people’s perceptions of immigrants by asking them which group of immigrants they would like to have as neighbors. There was a consensus among the respondents (mainly veteran Israelis) that the most preferable groups of immigrants (to have as neighbors) would be from Western Europe and America. In detail, the respondents said they would like to have an American immigrant, a French immigrant, and an Ethiopian immigrant (in that order) as their preferred neighbors (Frenkel & Shenhav, 1997). The same study also affirmed the same results when Frenkel & Shenhav (1997) asked the respondents to state which immigrant groups they would like their children to interact with at school. Coincidentally, these findings affirmed the findings of the University of Haifa (2010), which showed that Ethiopian immigrants were the least preferable immigrant group in Israel.

Previous researches affirm a negative perception of Eastern Europe and African immigrants in Israel (Frenkel & Shenhav, 1997; University of Haifa, 2010), some researchers have gone a step further and tried to investigate if these perceptions emanate from the media, or if they are unique to veteran Israelis (free from media influence). Information obtained from the Ashdod conference on immigration showed that many Israelis were against receiving immigrants from Eastern Europe and Africa (University of Haifa, 2010). Government records also affirmed this fact, when they reported that 24,000 Israelis did not support the immigration of Ethiopian and Eastern European immigrants in Israel. Rebacz (2010) says these government records are largely representative of the Israeli society because they represent 15% of the records (an accurate representation of the percentage of the immigrant population in Israel).

Rebacz (2010) says the negative representations of Israelis towards the immigrants are because of poor media perception. To affirm this fact, Rebacz (2010) says, “While the national imperative of immigration absorption continues to be espoused, and schools accused of limiting the number of their immigrant students are harshly criticized, the media should be doing their part as well” (p. 7). Comprehensively, through its power, the media has a huge role in shaping how most people think and perceive immigrants. For example, the University of Haifa (2010) remarks, “When the media continuously portray immigrants in a negative light, the public begins to internalize these stereotypes” (p. 1). The media, therefore, have a strong influence in defining the public structure of Israeli society.

How The Western Media Portrays Immigrants

The negative perception of immigrants in the media is not only limited to the Israeli media because researchers say many western nations tend to portray immigrants in a negative light (University of Haifa, 2010; Frenkel & Shenhav, 1997). This is especially true in the US, which manages several immigrant issues every day. Safipour & Schopflocher (2011) says that Western media tend to associate immigrant issues with illegalities. A report presented by the Brookings Institution, in 2008, described western media as presenting a narrative that “conditions the public to associate immigration with illegality, crisis, controversy, and government failure” (Rebacz, 2010, p. 1). In fact, through the role of the media in presenting a negative image of immigrants, Ross (2011) believes the media is largely to blame for the stalemates surrounding legislative processes in the US.

To investigate if only certain sections of the media portray a negative image of immigrants, Regina Branton (a professor at Louisiana state university) evaluated more than 1,200 media reports on immigration and found out that most media reports published in areas that are close to the border (like Mexico-US border) tend to portray immigrants negatively (Rebacz, 2010). Lenard & Straehle (2012) says the negative portrayal of immigrants by the media stems from the fact that most media companies are corporate-owned. Developed from a statistical model, outlining the above findings, Rebacz (2010) estimates that most Newspapers published in border cities have a 75% probability of portraying immigrants negatively (article news). Opinion pieces have a higher probability of the same negative portrayal of immigrants because Rebacz (2010) estimates that they have a probability of 85% of portraying immigrants negatively.

In sum, Frenkel & Shenhav (1997) believe that most people should understand the interaction between immigrants and Israeli state media within the context of nation-state formation. Here, Frenkel & Shenhav (1997) argue the media were an instrumental tool for championing national cohesion. The greatest barrier for achieving this goal was however the intense religious and ethnic overlaps of the Israeli society. The law of return complicated this goal because it gave immigrants automatic citizenship (with the understanding that Israel is a Jewish state). Nonetheless, despite the merits and demerits of these arguments, Cronin (2001) posits that in most parts of Israel’s history, people used the media as a propaganda tool for political lobbying in many western nations. The media also played an instrumental role in increasing the number of immigrants between Israel and Palestine (Cronin, 2001). The media aimed to uphold the spirit of nationalism by reinstating the Hebrew language, promoting agriculture, and advancing security issues (self-defense). The portrayal of these core pillars of nationalism played a huge role in defining the ways of life of new immigrants in Israel. Comprehensively, through the country’s political dominance of the media, the media defined the expectations of immigrants through the advancement of the nationalism spirit.

Methodology

Research Design

So far, many studies have only focused on exploring how the Israeli media covers immigrant issues and how the content of such media affects the immigrants. However, this narrow focus bypasses media uses and practices. From this background, this paper adopted the media-ethnographic discourse approach to understanding the coverage of the Israeli media on immigrants and the aftermaths of such coverage. This method is an offshoot of a combination of qualitative and quantitative techniques in collecting the research data (mixed research approach). The appropriateness of the media-ethnographic discourse approach in conducting the research stemmed from its ability to describe meaning in social life (Schiffrin & Tannen, 2008).

Therefore, the media-ethnographic discourse approach made it easy to investigate the hidden meanings, complexities, and messiness of the research questions. Moreover, this approach captured the multi-strategy approach that underlies the research topic (a combination of social and political meanings). The research design, therefore, played a huge role in helping to discover and interrogate the meanings surrounding the significant issues underlying the research topic. Through the same approach, it was also possible to provide contextual meaning to the study’s findings, including the time and space components of the findings. Comprehensively, the appropriateness of the media-ethnographic discourse approach in this study sums in the words of Thurlow & Mroczek (2011) when they said, “ethnography is at once a research methodology, a set of fieldwork techniques, most prominently participant observation, and a research product, a reflexive account of social life that values participants’ perspectives” (p. 12).

Participants

To avoid any complexities that would arise from analyzing different media contents, this paper mainly focused on the perceptions of the immigrants by interviewing three focus groups that represented the main immigrant populations in Israel (US and western European immigrants, Eastern European immigrants, and African immigrants). Of importance to the researcher was the need to comprehend how media perceptions of immigrants affect their well-being, comfort, and the perceptions of their status in Israel. Indeed, based on the ethnic and racial characteristics of the main immigrant groups in Israel, this paper strived to provide a holistic representation of immigrant perceptions in Israel by interviewing a representative sample of the immigrant population of Israel. The total sample population comprised of 15 immigrants. This population represented five respondents from each of the three immigrant groups. The participants had to have lived in Israel for more than 20 years (the study excluded new immigrants). The participants’ age ranged from 30 years to 50 years). There was no gender bias in the selection of the respondents, but there were fewer women willing to participate in the study (there was no motivation to understand the reasons for this outcome). Nonetheless, three of the respondents were women. Two of them were immigrants from Western Europe and one was an immigrant from Eastern Europe.

Data Collection

To understand the perceptive understanding of the coverage of immigrants in the Israeli media, this paper used interviews as the main data collection method. The interviews were semi-structured to allow the researcher to focus on the research questions and to give the respondents some room for answering the research questions (comfortably). Part of the motivation for using a semi-structured interview was also to accommodate the varying dynamics of the immigrants sampled. Indeed, since the immigrants came from three groups (Western Europe and US immigrants, Eastern European immigrants, and African immigrants), it was important to structure the interviews to accommodate their differences.

The interviews included face-to-face interactions at the homes of the respondents. This setting was ideal for the convenience and comfort that it gave the respondents. Since most of the respondents had varying schedules and demands for conducting the interviews, the interview occurred at their convenience. This way, there was an increased sense of commitment and enthusiasm from the respondents to participate in the research. The respondents also took their time to answer the questions. In sum, all the 15 interviews ended in a month. The interview consisted of a set of 12 main questions.

- What media sources do you listen to, or watch?

- How do you think the media portrays immigrants in Israel?

- How do you perceive your treatment as immigrants?

- Do you believe there is a link between how you are treated as an immigrant and how the media portrays immigrants?

- What mechanics of media scrutiny do you use to evaluate how the media perceives you as an immigrant in Israel, and what are their impacts, if any?

- What are native Israelis saying about how the media perceives you?

- Do you believe there is a distinction in the way different types of media perceive immigrants?

- Do you believe the media has a lot of power in defining the way native Israelis perceive immigrants?

- Do you believe the media portrays all immigrants as the same?

- How do you relate with immigrants from other ethnic or regional backgrounds?

- What do you think is the future of immigrants in Israel, in relation to how they integrate in the Israeli society?

- What is your expectation of how the media should portray immigrants in Israel?

Data Analysis

Since this research mainly included qualitative interview data, the discourse analytic method emerged as the most appropriate technique to analyze the deeper meanings of the responses. This method was highly useful for the researcher because it did not only produce versions of the interviewees’ responses, but also identified interpretive patterns in their views.

Thurlow & Helms (2009) say this analysis method is highly context-dependant and therefore provides a contextual analysis of the responses, as opposed to an abstract understanding of the views of the interviewees. The discourse analytic method therefore helped to understand the views of the respondents by understanding contextual regularities of the informants’ accounts, at a macro-sociological level.

Results Review

At the end of the interview process, the analysis of media coverage of immigrants mainly drifted towards understanding the influence of television as the most preferable and common type of media. Print media also emerged as a common type of media consumed by the respondents, while radio emerged as the least preferable media, although the most common. Albeit the respondents admitted to consuming different types of media, they unanimously agreed that the Israeli media does not fairly report on immigrant issues. Many of the respondents believed the media was biased and determined to reinforce existing perceptions about immigrants. Some felt the Israeli media was similar to other types of media in other western countries, especially concerning how they portrayed immigrants. A few respondents compared the Israeli media to Western European media and American media. They said both types of media “demonized” immigrants by creating a negative public perception towards them. One respondent said there was a close relationship between the Israeli media and the Swedish media because both outfits portrayed immigrants in a negative light.

Unanimously, the respondents also drew the link between the negative portrayal of immigrants in Israel and their treatment/experiences in society. Many interviewees believed their negative experiences stemmed from how the media portrayed immigrants. However, there was a slight variation regarding the views of immigrants from the US and western European backgrounds. They did not agree that their experience as immigrants in Israel was negative. One respondent, of American descent, affirmed this fact by saying he could not define his experiences in Israel as being entirely bad. He further elaborated that,

“There are times I am normally happy, there are some times I am sad. I cannot say my experience is entirely bad because there are some things I am happy about and there are some things I do not like. See, all of us have different experiences, it all depends on a person, but for me, I guess I sit on the fence,” he added.

The respondents that affirmed a negative experience as immigrants in Israel did not shy from blaming the media for their woes. One respondent said the media were synonymous with character assassination.

“They portray us very badly, almost like we should not be here, like we are unwanted. Sometimes you cannot see it because they hide it, but you feel it. They say the right things, but do the complete opposite. It can be very uncomfortable sometimes,” she added.

When the respondents were asked to explain how media coverage influenced their perceptions as immigrants, most respondents not only affirmed the influence of the media on how they perceive themselves as immigrants in Israel but also how native Israelis perceive immigrants. The main outcome from this analysis was the role of the media as a counterproductive tool that deepened the divisions between the Israeli native society and the immigrant population. Stated differently, the media enforced existing stereotypes regarding immigrants in Israel. Most of the respondents also claimed that the media contributed to essentialism, especially concerning how they portrayed immigrants. For example, one respondent said the media adopted a broad definition of everybody that was not a native Israeli as an “immigrant.” He added,

“I think the media portrays all of us negatively. It does not matter where we come from. This negative perception of immigrants may affect everybody, the Israelis too, because they would think that we are all the same. However, the truth is, we are not.”

Rydin (1996) hinted at the effect of media generalizations on immigrants by saying, “together the media give shape to a comprehensible immigrant, an intellectual construction that lives a life of its own, beside real people and circumstances” (p. 342). Through his analysis, Rydin (1996) portrays the media as a superficial outfit that is out of touch with the real circumstances of characterizing immigrants. Rydin (1996) also questions our understanding of the term, immigrants because he says we should all look beyond the abstract meaning of the term and consider the racial, discriminatory, and ethnic undertones of the term. Here, he says the term, “immigrant” (as used in many western contexts) means failing to share commonalities with the dominant (majority population). He also says, “In a deeper sense, being an immigrant is being an insignificant person” (Rydin, 1996, p. 16).

When the respondents had to describe how they felt the media portrayed them, one Ethiopian immigrant asked the criteria people use to term them as immigrants. He said,

“Okay, we read media reports about crime and they say, well, he is an immigrant, or perhaps he is born of immigrant parents and therefore they share an immigrant background. Some of us have lived all our lives here. I know people who have stayed in Israel for even 50 years. Why do they still call us immigrants?”

One immigrant from Egypt also affirmed the views of the above respondent by questioning the criterion used by the Israeli media (and the Israeli native population) to classify immigrants. He said,

“They call us immigrants just because we do not share a common heritage with them. I may be mistaken, but if somebody is born in a country, and is a citizen of the same country, why do they still call him/her an immigrant? Is it because we have different names, or what?”

When the respondents had to describe the power of the media in defining immigrants, most of them appeared to mirror the contents of the classical theory of cultivation. This theory shows that the media has the power to create an image of people, which consequently affects the way the public perceives such people (Rydin, 1996). Relative to this assertion, Morley (1999) argues, “Thus the norms of that television world naturally come to define, for many people, the basic contours of how it really is, out there in the big wide world, beyond their immediate personal experience” (p. 144).

A discussion of the nature of relationships among the different groups of immigrants showed that they all existed cohesively. This result showed that even though there was a significant cultural difference between the different groups sampled, they all seemed to co-exist well. However, a key finding that emerged in this analysis was the commonality in plight. The respondents said the media brands them all in the same manner and therefore, there was no need to dislike one another because of small misconceptions.

When the interviewees had to explain how native Israelis thought the media perceived them, they affirmed the earlier observation that the media has greatly influenced how most people see them. Most of them expressed frustrations at the disregard for immigrant groups in Israel. In fact, most of the respondents, except for one immigrant from Western Europe said native immigrants thought the media painted an accurate picture of immigrants in Israel. “This was untrue,” one added. Therefore, many of the interviewees believed the media had a huge role in defining how native Israelis perceived them. This conviction also reflects earlier observations that expressed the respondents’ belief concerning the powerful role of the media in shaping public perceptions about immigrants.

Coincidentally, when the interviewees had to explain their modes of media evaluation, they identified the views of native Israelis as their focus for understanding the effectiveness of the media. One respondent said,

“See, the media and public perceptions are almost the same thing. The media influence public perception about us. I mean, if the local population here does not see us as villains, the way the media tries to portray us, it means the media is unsuccessful. However, this is not the case. They despise us. They think we are not worthy of their time. It is all because of the media. They portray us very badly. This is how I evaluate the media – people’s perceptions. That is all I am saying.”

When the respondents had to state which media they relied on, 12 respondents said they liked to listen, watch, and read all types of media. Only three respondents said they prefer to consume local media, as opposed to Israeli media. They said they decided to do so because they believed Israeli media was highly biased against them. Other respondents said they consumed local media only when they wanted to know what was happening in their native lands. However, they preferred to consume Israeli media. In sum, most of the respondents said they preferred to consume Israeli media. The criterion for selecting the respondents may have contributed to this observation. All the respondents had to have lived in Israel for more than 20 years. Therefore, many of them had already assimilated into Israeli society and lost touch with their countries of origin.

When the respondents had to state if they saw any difference in how different media channels portrayed immigrants, all the informants said there was no difference among the media channels. To explain this position, one respondent said,

“All media is the same, they all start by reporting what happened in the country, then they report what happened around the world, followed by sports news, and then probably they would conclude by talking about the weather. There is no difference.”

When the researcher demanded more specifics about the representation of specific immigrant issues by the media, this respondent said,

“You see, most media outlets here do no work to promote peace. It is like they all work together to support segregation, as opposed to integration. I hope you get me right, I mean, there are some good people. Like when you come here first, they receive you well, but those who see television a lot are unfriendly”

Interestingly, albeit the respondents said the media stereotyped them negatively, there was a weak indication by the immigrants that the media profiles different immigrant groups differently. Except for one respondent who said some media tend to portray West European and US immigrants in a positive light, the rest believed most of the negative connotations propagated by the media applied to all of them. In fact, one respondent said,

“…For example, look at crime, they do not openly say it, but you tend to have a feeling that they attribute some type of crime to the presence of immigrants in Israel. There is often little time to dice up immigrants into small groups to see who contributes to crime. They all put us in one category and say, they are spoiling our society, since we are poor, I guess”

Through such assertions, the respondents did not support the belief that the media perceived Western European immigrants and U.S immigrants in a more favorable light than other groups of immigrants. The minimal reference to this difference however negates the notion that previous researches may be wrong.

Lastly, when the interviewees had to state their understanding of the future of immigrants in Israel, most of them expressed pessimism concerning a change in the current situation. However, three respondents from Western Europe expressed some optimism regarding the treatment of immigrants in the future. One said, “You know, as much as immigrants do not get the same type of treatment as ordinary Israelis, the situation has improved. It will continue to improve in future because the world is more cohesive now than it was before.” This assertion also outlined the expectations of the respondents regarding the portrayal of the media towards Immigrants. Although many informants believed the media would not change in the immediate term, most of them hoped that there would be more efforts by the media to paint an accurate picture of immigrants, as opposed to reinforcing the existing stereotypes. Stated differently, many of the respondents expected a fairer representation of immigrants in the future.

Data Analysis/Conclusion

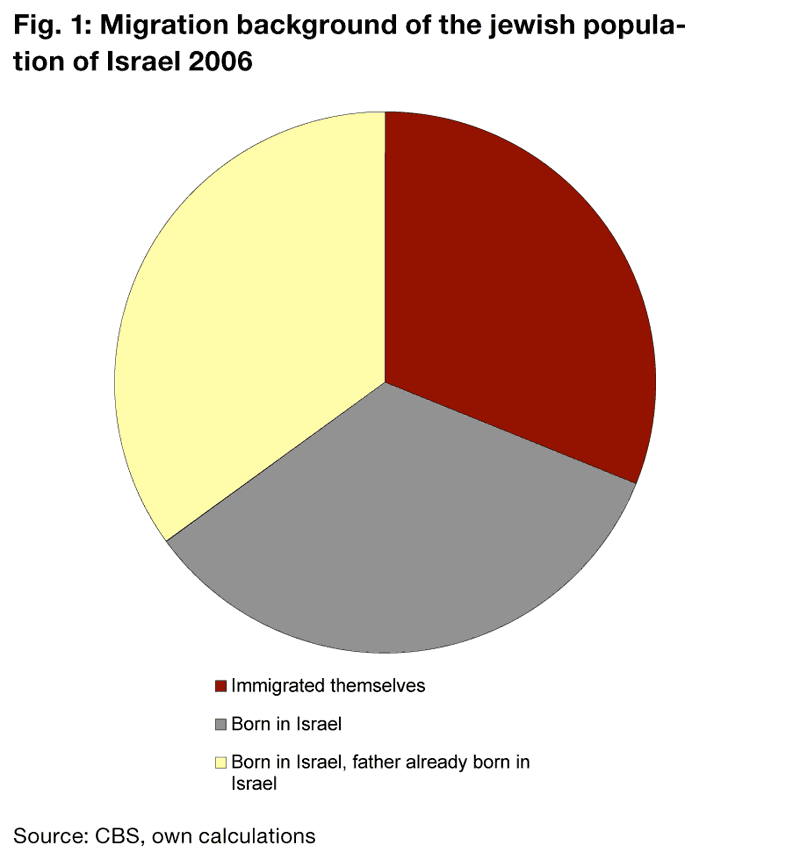

A key concern raised by some of the respondents sampled was the justification for referring ethnic minorities as immigrants, despite their citizenship status and their long stay in Israel. According to the diagram below, this argument has some merit because the majority of immigrants in Israel were born in Israel, or one parent was born there. Through this assertion, it is correct to say most of the immigrant population in Israel only fit this description, based on their ethnic backgrounds, but not because of their status as citizens of Israel.

Through the above diagram, it is also easy to see that the percentage of immigrants who migrated to Israel voluntarily only comprise a small section of the Jewish population (compared to immigrants born in Israel, or had a parent born in Israel). Nonetheless, the status of immigrants in Israel only outlined a small concern among the respondents because most of their frustrations focused on the country’s perception of immigrants.

It is easy to comprehend the feelings expressed by the respondents through the works of Stuart Hall (a cultural theorist). Hall introduced the interpretive framework for understanding the ideological meanings of media texts by saying that most people who feel afflicted by media reports prefer to block the dominant message and adopt the opposite message (Procter, 2004). Stated differently, Procter (2004) says the main message advanced by the media describes a dominant hegemonic position of the society. Therefore, if we extrapolate this view, easily, we see that the negative portrayal of immigrants in Israel constitutes this position.

However, based on the responses gathered from the interviewees, the immigrants prefer to adopt an oppositional reading of this position. The oppositional code occasionally agrees with the underlying media position, but often, it questions this position. Sjöberg & Rydin (2008) say this reading of media texts denotes the introduction of semiotics into the analysis of communication processes. However, there is surety among most researchers that most media meanings are products of social and cultural forces. To assert this position, Sjöberg & Rydin (2008) say, “The semiotic meanings may include everything from the broader ideological discourses in a specific society to a person’s unique history, experience, and knowledge” (p. 4).

The findings of Stuart Hall compared to similar studies by Morley (1980) in his work titled, Nationwide Audience. Morley (1980) evaluated the influences of class and ethnicity in evaluating people’s perceptions of how they comprehended media messages. Many experts say genre influences have a profound impact on how many people understand media messages (Procter, 2004; Morley, 1980; Rydin, 1996). Reports that support this view show that most respondents tend to view media messages as closed-ended (aimed at driving a specific message), as opposed to open-ended, as would be the case in a soap opera (or similar entertainment programs) (Morley, 1980). Rydin (1996) supports this view when he suggests, “different genres invite different types of readings and media discourse strategies” (p. 51).

The above assertions largely explain the widely negative opposition of the respondents to how the media portrays them. In fact, in most of the responses given by the interviewees, there was an opposition to the view that the media paints an accurate representation of their lifestyles, beliefs, and values. There is therefore sufficient reason to believe media reports on immigrants in Israel are stereotypical. Using Hall’s model to arrive at this conclusion should however be understood within contextual precincts because Hall’s works are contextual (Procter, 2004).

In the presentation of these findings, people should understand that the findings of this paper developed from the adoption of the constructivist approach. This approach underlines the importance of merging people’s perceptions of technology. Thus, the perceptions of immigrants are a product of their cultural influences. Stated differently, the immigrants conceive and interpret media messages, depending on how such messages fit into their cultural understanding/everyday life. Sjöberg & Rydin (2008) support this view by saying media focus always shifts to significant societal issues that have the power to influence prevailing social norms. These shifts mainly aim to challenge the prevailing cultural environment by questioning the relationship between people and institutions, and the influence of such relationships in defining public perception.

The above analogy shows that social constructivism is a holistic approach that captures the views of immigrants because they provide a good environment for integrating micro and macro perspectives of the interviewee’s views in the study. This analysis also provides an inter-agency approach to how the immigrants select and interpret their reality. The interactions between the micro and macro perspectives are comparable to the interaction between the views of the immigrants and technology (this interaction is a continuous negotiation) (Sjöberg & Rydin, 2008). The process of interpreting the meanings of the researchers through the constructivist approach is an old method adopted by researchers in the past. In fact, many researchers have used the constructivist approach to understand the importance of media in people’s social lives. For example, Alasuutari (1999) has emphasized the importance of adopting the constructivist approach in cultural studies because he affirms a change of interpretive paradigm from focusing on how the media influences people’s mental understanding of societal issues to how the media plays a role in complementing people’s lives. This gradual shift of interpretative framework has largely redefined how media makes sense to people today.

The use of discourses in this analysis shows that the interpretations of immigrants mainly depend on the presentation of media texts and the analysis of informants. The findings of this paper have investigated different kinds of recognitions and emotional attachments, plus their effects on the perceptions of the immigrants. The effect of the media in shaping public perceptions about immigrants however stands out as an undisputed fact in this analysis because of the unanimous acceptance (of the respondents) that public perceptions affect how the media perceives them.

The findings identified in this paper support similar findings conducted by other researchers in other regions. For example, this paper shows that different immigrant groups feel they receive the same type of treatment, regardless of their backgrounds. Sjöberg & Rydin (2008) reported the same finding after investigating the coverage of immigrants in Sweden because his respondents said the media often generalized immigrants. This generalized portrayal of immigrants shows that there is a general representation of immigrants by most western media (Sjöberg & Rydin, 2008). A comparison of these findings and the findings of Sjöberg & Rydin (2008) also show that the media also often cover negative images about immigrants, as opposed to communicating positive messages about immigrants.

Particularly, this is true for this study and other studies conducted in Europe. For example, the study of Swedish media shows that they often concentrate on highlighting poverty and criminality whenever they highlight issues about immigrants (Sjöberg & Rydin, 2008). Studies that investigate the same relationship in America also show that the media often highlights negative issues about immigrants. The same is also true for studies conducted in Britain because Schiffrin & Tannen (2008) say British media often relate negative social issues (like crime) with immigration. There is therefore a general sense of understanding that most media misrepresents immigrants and their way of life.

Future studies should investigate how immigrants position themselves at the center of how the media covers them. Future researchers may analyze different issues here, like how media coverage of immigrants affects their self-perception, self-esteem, and lifestyle. Similarly, researchers should investigate how media coverage of immigrants affects how the immigrants perceive Israelis. A key issue of concern that may arise in this analysis includes an investigation into whether media coverage reflects the perception of Israelis, or misrepresents the views of the native Israelis.

References

Alasuutari, P. (1999). Introduction: Three phases of reception studies: Rethinking the media audience. London, UK: Sage Publications Ltd.

Boneh, D. (1991). Immigrants from Russia: A Marketing Challenge for Israel’s Banks. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 9(3), 9 – 10.

Cronin, B. (2001). Information warfare: peering inside Pandora’s postmodern box. Library Review, 50(6), 279 – 295.

Focus-Immigration. (2013). Israel: Focus on immigration. Web.

Frenkel, M., & Shenhav, Y. (1997). The political embeddedness of managerial ideologies in pre-state Israel: the case of PPL 1920-1948. Journal of Management History, 3(2), 120 – 144.

Gavish, H. (2010). Unwitting Zionists: The Jewish Community of Zakho in Iraqi Kurdistan. Detroit, Michigan: Wayne State University Press.

Kushnirovich, N. (2010). Ethnic niches and Immigrants’ Integration. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 30(7), 412 – 426.

Lenard, P., & Straehle, C. (2012). Legislated Inequality: Temporary Labour Migration in Canada. London, UK: McGill-Queen’s Press.

Morley, D. (1980) The ‘Nationwide’ audience: structure and decoding. London, UK: BFI.

Morley, D. (1999). Television and common knowledge. London, UK: Routledge.

Neuman, S., & Oaxaca, R. (2005). Wage differentials in the 1990s in Israel: endowments, discrimination, and selectivity. International Journal of Manpower, 26(3), 217 – 236.

Nonna, H. (2008). The impact of policy on immigrant entrepreneurship and businesses practice in Israel. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 21(7), 693 – 703.

Procter, J. (2004). Stuart Hall. London, UK: Routledge.

Rebacz, M. (2010). Is local reporting contributing to anti-immigrant sentiment? Web.

Ross, K. (2010). Gendered Media: Women, Men, and Identity Politics. London, UK: Rowman & Littlefield.

Ross, K. (2011). The Handbook of Gender, Sex, and Media. London, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

Rydin, I. (1996) Making sense of TV-narratives. Children’s readings of a fairy tale (Published Ph.D. thesis). Linköping, Sweden: Linköping University.

Safipour, J., & Schopflocher, D. (2011). Feelings of social alienation: a comparison of immigrant and non-immigrant Swedish youth. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 31(7), 456 – 468.

Schiffrin, D., & Tannen, D. (2008). The Handbook of Discourse Analysis. London, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

Sjöberg, U., & Rydin, I. (2008). Discourses on media portrayals of immigrants and the homeland. European Journal of Communication, 25(28), 1-26.

Thurlow, A., & Helms, J. (2009). Change, talk and sensemaking. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 22(5), 459 – 479.

Thurlow, C., & Mroczek, K. (2011). Digital Discourse: Language in the New Media. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

University of Haifa. (2010). Reportage on Israel’s Ethiopian, Russian Immigrants Focused On Their Differences from Israeli Norms. Web.

Wendehorst, S. (2011). British Jewry, Zionism, and the Jewish State, 1936-1956. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.