Introduction

Today, the ability to identify infectious diseases quickly and efficiently is a significant factor in managing disease outbreaks. Consequently, unconventional methods of infectious disease surveillance have emerged to replace traditional surveillance schemes. The aim of this essay is to investigate social media or Twitter as unorthodox approach to infectious disease surveillance in the US, particularly in the case of flu. It compares social media surveillance and traditional surveillance schemes.

A context of the disease under surveillance

The traditional modes of infectious disease surveillance can no longer cope with rapid changes associated with movements of people. Consequently, researchers have found new ways in social media, particularly Twitter and Facebook to provide for surveillance in detecting the outbreak and spread of infectious diseases within a given place, state, region, or globally.

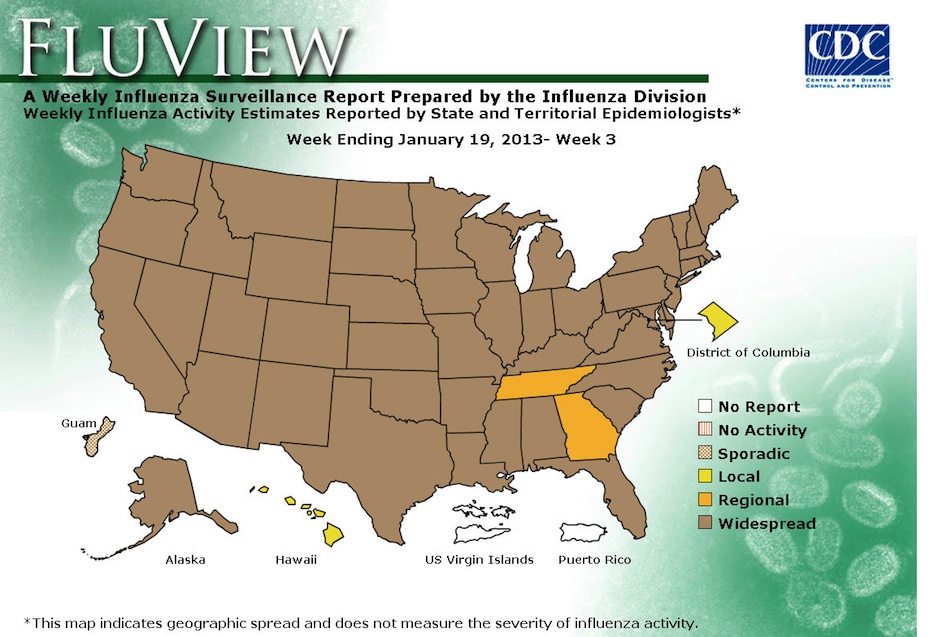

In January 2013, the USA experienced a severe flu outbreak, which was spread across the country based on data from the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012).

According to CDC (2012), flu infection was particularly severe in December 2012 when the number of hospitalised patients and deaths associated with the flu infection was raising steadily. Although there was a slight decline in cases of flu in January 2013, the national figure was still high. The Centre noted that people were hospitalised between October 2012 and January 2013 because of flu as well as 37 children died from flu nationwide.

Researchers wanted to understand the raise or decline of flu within the US. Consequently, they turned to social media for information (Polgreen, Chen, Pennock and Nelson, 2008).

Aims or objectives of the system and the rationale for its use – a comparison to traditional surveillance schemes

Social media, particularly Twitter and Facebook, could provide useful public health data needed for infectious disease surveillance. The outbreak of flu in the US led to emergence of Twitter-based flu projections. There were considerable numbers of tweets about the flu, such as, “I’m so sick this week with the flu” (Sneiderman, 2013). Such comments indicated potential progress in flu cases. Therefore, the evaluation of the scope and severity of flu outbreaks can be provided with the help of gathered tweets.

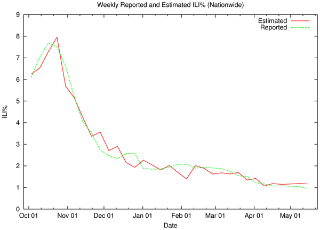

The traditional flu surveillance by CDC involves collecting information from outpatient reports and conducting virological tests on samples collected by public health facilities nationwide. This approach can only provide results to confirm outbreaks after two weeks. On the other hand, social media have provided real-time results in cases of immediate concerns (Christakis and Fowler, 2010).

Social media aim to transform how public health officials respond to flu outbreaks and other diseases (Schmidt, 2012).

The sites provide aggregates of affected locations within a global map, which displays outbreaks in real-time (Schmidt, 2012). Conversely, applying traditional model, public health officials spend several weeks gathering data from victims privately. It was difficult for the public to access that data collection as flu outbreak investigation was ongoing, and it took time for public announcements of the results. An influenza-related Twitter map from Signorini, Segre and Polgreen (2011) depicted the outbreak.

Social media aim to provide early warnings in areas of concerns. For instance, Google developed Google Flu Trends to allow users to contrast volumes of flu-related activities on the Web sites against the reported cases (Ginsberg et al., 2009). This resulted in graphical representation of flu on the map (Carneiro and Mylonakis, 2009). Thus, public health officials can use such information for immediate responses.

According to Chunara (2012), analysis of news and Twitter feeds from earlier periods of the outbreak in 2010 indicated that such data were valuable and could be used for reporting rather than for waiting for more than two weeks to get government reports.

Unconventional methods of flu surveillance could be deployed globally as cost-effective and efficient methods of detecting an outbreak of an epidemic and then intervening at the right time with appropriate medication.

Core functions of the system

The core function of social media surveillance is to collect real-time data as quickly as possible about an onset of the flu and prepare a response when necessary. This is more rapid than the traditional surveillance method in which public health officials had to gather data after the outbreak and take several weeks before making public announcements.

Researchers noted that some of the tweet feeds that streamed and tracked cases of influenza-like illnesses (ILIs) were also critical for providing information about the flu (Ortiz et al., 2011), although such illnesses have their own viral aetiology. At the same time, researchers have developed a new method of screening flu-related tweets. They can extract real-time data on flu cases and eliminate other tweets that do not necessarily relate to real flu infections (Sneiderman, 2013).

Researchers have used data from Twitter feeds to develop the US flu maps, which indicate the possible variations between the previous year’s flu outbreak and current incidence of flu onsets.

Therefore, the use of social media posts show that such data can be used effectively to inform public health officials as they respond to outbreaks of flu and other infectious diseases. This would better enhance infectious disease surveillance than other traditional approaches do. Moreover, the approach of social media surveillance may also be applicable in tracking other diseases.

Garritty notes that many epidemiologists consider social media as an advantage in understanding onsets and progression of infectious diseases (Garrity, 2011). As a result, studies on pathogens may depend significantly on Twitter streams by using specific terms like flu, mumps, influenza, and infection among others in the future (Signorini et al., 2011).

Potential and challenges of the system

Although reviewing social media comment to track flu cases, when they occur, has become a common practice, there are critical concerns with this type of infectious disease surveillance approach.

The use of social media to track flu cases is in its infancy stage. Consequently, it has several weaknesses. One major challenge is how to locate flu-infection tweets from other related tweets. For instance, some tweets originate from people who are infected with the virus, whereas the others may be posted by individuals who are just making some comments (Sneiderman, 2013). Therefore, scientists who track the actual flu outbreak may collect data, which could yield skewed results.

Conversely, the use of social media in flu surveillance offers a quick and cost-effective method of assessing flu epidemic and allows public health officials to track infectious disease in its earliest stages after the outbreak.

Given that infectious disease spreads as fast as infected people can move, it is sensible to adapt the speed and flexibility that social media offer in disease surveillance.

Critics have argued that such new systems of infectious disease surveillance only offer illusion of effective disease tracking (Garrity, 2011). This could be associated with the heavy use of social media in large cities among technology savvy users. Hence, results could be skewed. Moreover, not everyone relies on social media for communication. Thus, the result might not be representative of the entire population.

Some scientists have cautioned that such online activities may not necessarily relate to the outbreak of flu (Schmidt, 2012). For instance, whenever celebrities tweeted that they had flu or related symptoms, flu-related searches increased rapidly. Any researcher can notice that timing of the rise in tweets also coincide with such celebrities’ flu-related queries. In other words, the public reacted out of curiosity, but not because of actual flu outbreaks. Such Twitter feeds have minimal impacts on helping public health officials to prepare the public for potential outbreaks in the future.

The Google Flu Trends application aims to eliminate challenges associated with media bias. The system models search terms to identify the most stable ones over time. The method strives to eliminate ‘noisy queries’ (searches that do not relate to changes in flu outbreaks and progression) and avoid data vulnerability.

Some critics have noted that too many tweets that relate to flu news reports and other issues that do not directly relate to the flu epidemic may affect their reliability and weaken computer-based surveillance models. Currently, researchers have enhanced their studies to improve accuracy of tweet feeds for tracking flu outbreaks. Sneiderman notes that researchers have developed “sophisticated statistical methods based on human language processing technologies, which are designed to filter out the chatter” (Sneiderman, 2013). That is the tracking tool which is able to distinguish between terms used by infected persons and those applied by people expressing their concerns.

Social media surveillance system generates real-time results, and it can be used for future predictions of flu outbreaks (Kostkova, Quincey and Jawaheer, 2010). On the other hand, the CDC traditional system of surveillance collects data from patients and takes over two weeks to publish the outcomes.

One must note that online chat platforms could be unproductive and highly risky because they can spread propaganda, misinformation, and fear, which relate to cause and cure of diseases. However, a significant number of epidemiologists have noted the benefits of social media in infectious disease surveillance. Therefore, it is imperative to develop social media surveillance for future tracking of infectious diseases and other emergencies.

Conclusion

Initially, people used social media to post frivolous remarks about lifestyles. However, this has changed over time. Today, social media, such as Twitter and Facebook, and other micro-blogging sites have evolved to become useful tools that people use to communicate with each other to inform about emergencies, infectious diseases outbreaks, and other cases that require immediate responses.

Although the social media surveillance system faces some challenges relative to traditional surveillance models, it offers real-time data for immediate actions.

References

Carneiro, H. A., and Mylonakis, E. (2009). Google trends: a web-based tool for real-time surveillance of disease outbreaks. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 49(10), 1557- 1564. Web.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012). Seasonal Influenza (Flu). Web.

Christakis, N. A., and Fowler, J. H. (2010). Social network sensors for early detection of contagious outbreaks. PLoS ONE,5(9), e12948. Web.

Chunara, R. (2012). Social media enabled fast tracking of cholera vs. traditional surveillance. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 86, 39-45.

Garrity, B. (2011). Social Media Join Toolkit for Hunters of Disease.The New York Times. Web.

Ginsberg, J., Mohebbi, M., Patel, R., Brammer, L., Smolinski, M., & Brilliant, L. (2009). Detecting influenza epidemics using search engine query data. Nature, 457(7232), 1012–1014. Web.

Kostkova, P., Quincey, E. de., and Jawaheer, G. (2010). The potential of Twitter for early warning and outbreak detection. Web.

Ortiz, R., Zhou, H., Shay, K., Neuzil, M., Fowlkes, L., and Goss, C. (2011). Monitoring Influenza Activity in the United States: A Comparison of Traditional Surveillance Systems with Google Flu Trends. PLoS ONE, 6(4), e18687. Web.

Polgreen, M., Chen, Y., Pennock, M., and Nelson, D. (2008). Using internet searches for influenza surveillance. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 47(11), 1443–8.

Schmidt, C. W. (2012). Trending Now: Using Social Media to Predict and Track Disease Outbreaks. Environmental Health Perspectives, 120(1), a30–a33. Web.

Signorini, A., Segre, A., and Polgreen, P. (2011). The Use of Twitter to Track Levels of Disease Activity and Public Concern in the U.S. during the Influenza A H1N1 Pandemic. PLoS ONE, 6(5), e19467. Web.

Sneiderman, P. (2013). Using Twitter to track the flu: Researchers find a better way to screen the tweets. Web.