Introduction

Background Information

According to Kristin Henriksen (the author of Statistics Norway), female immigrants make up a large portion of the Norwegian population (Kristin, 2011). She points out that by the year 2010 the population of immigrants in Norway was close to 400,000. The number of female immigrants in the country is slightly higher than that of their male counterparts-close to 205,000 compared to 195,000. 170,000 of the female immigrants in the country are first-generation while 35,000 are second generation (Kristin, 2011).

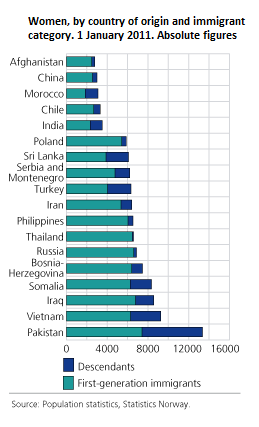

Kristin (2011) posits that female immigrants of Pakistani descent form the largest group of immigrants that are not from a western nation. In total, approximately 8 per cent of all female immigrants in the country are from Pakistan. Approximately 7,500 of female Norwegian-Pakistani immigrants were born in Pakistan while 6,300 are second generation. Figure 1 below shows the population of female immigrants in Norway by the beginning of 2011. Female second-generation immigrants from Pakistan form the largest descendants group in Norway. Less than 5 per cent of the descendants are beyond 30 years of age.

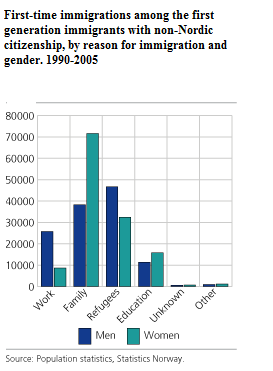

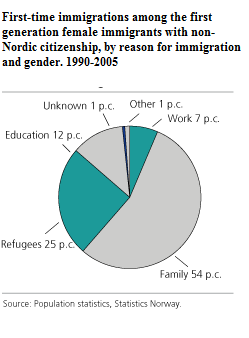

Pakistanis immigrate to Norway because of diverse reasons. However, most of the women immigrate to the country because of family relations while most men come to Norway as refugees. Blau, Kahn & Papps (2011) are of the view that the reason for immigration is very important when it comes to interpreting male and female immigration disparities.

Kristin (2011) adds that from 1990 to 2006, 65 per cent of all immigrants from a Pakistani descent who came into the country because of families were women. The main reason is that most men leave the home country as refugees and later on their nuclear families follow them.

Nanc (2005) points out that the women make up the minority of persons arriving in Norway as refugees (not including those arriving under family immigration). From 1990 to 2005, 4 out of ten refugees were women. 42 per cent of all Pakistanis who came to Norway in pursuit of higher education within the same time were women. Very few women come into the country as labor immigrants. 40 per cent of all female immigrants live in the Østland region (this includes Oslo and Akershus). 55 per cent of women in the country’s general population are married, 60 per cent of immigrant women from a western background are married while 75 per cent of female immigrants from Pakistan are married (Kristin, 2011).

According to Green (2012), one of the most dramatic transformations in the developed world has been the increasing number of women who have been through post-secondary education and joined the job market. This particular transformation has increased the level of independence among women in these nations. These changes in gender access to education and the job market are also being experienced in developing and transitional economies (Amuedo-Dorantes & Grossbard, 2007). This quest has not only increased the level of autonomy among women but also their role in economic development. However, Nanc (2005) asserts that the rate of female labor participation has been slower than the rate at which the educational gap is narrowing.

This is noted to be the case among immigrant women from Pakistan living in Norway. According to Hotchkiss, Pitts & Walker (2010), this suggests that there are other factors that determine their participation in the labor force. Some of these factors include 1) social norms on women’s role in the economy, 2) the relevance and content of contemporary higher education and 3) the characteristics of the job market that affect the demand for female workers. The three authors add that the first two factors can be influenced to some degree by the system of education while the third mainly operates outside the system. Kristin (2011) notes that in order to understand the role of educational training among Norwegian-Pakistani women, it is essential to look at the role of family background on occupational outcome.

Scott, Crompton & Lyonette (2010) posit that the occupational qualification of an individual determines the human capital they offer in the labor market. It is not possible to provide a precise measurement of such qualification. Franci, Parasuraman & Kim (2012) note that in countries such as Norway where the markets are developed and labor categories are quite ambiguous, qualification is to a large extent determined by the kind of work. This is the reason why many Norwegian-Pakistani women have been employed in areas they did not receive educational training in. Although many of the women have received vocational training in Norway there, is little correspondence between the training they have received and what is expected of them at work.

Additionally, Green (2012) points out that educational attainment is just a part of the qualification of the labor force. Therefore, there is need to recognize the limits thereof when using it to measure the labor force qualification of the population. First of all, there is no definite correspondence between vocational aptitude and educational proficiency. Measures of educational attainment are not in a position to change at the same speed with the changes in the qualifications and skills that are needed at the workplace. The labor world and the formal education sector have different articulation degrees.

Moreover, Bhatti & Shar (2010) argues that in the case of female immigrants who received their educational training in Pakistan, there are major differences between the two systems of education. This has to do with the certifications for different retention levels and stages outlined in the system. For instance, the point at which study streams diverge into academic and vocational training differs widely. In this case, the duration and stages of study are not comparable.

Green (2012) adds that another important difficulty in the use of educational attainment to determine professional qualification is that virtually all the data that is used to measure attainment is presented in formal education terms. In this case, it becomes difficult for Norwegian-Pakistani women to participate in the labor market in spite of having competencies and skills they acquired from informal training and education while employed in organizations.

Furthermore, there is a challenge in the use of educational attainment to measure professional qualification. This is because it is not always easy to measure “real” educational achievement (Bhatti & Shar, 2010). Both countries have systems of examining students but the fact is that the criteria of evaluation and examination are different. In this regard, first generation Norwegian-Pakistani women are affected because their educational qualifications reflect different achievement levels.

Problem Statement

According to Benito & Bunn (2011), education is fundamental because it provides personal cognitive and affective development. It also passes culture, traditions and values between generations while at the same time providing scientific and social progress.

Ultimately, the fruits of education go a long way in changing the economic status of individuals and their countries. Naveed, Ullah & Ashraf (2011) assert that this takes place in two broad ways. First, education expands scientific knowledge and transforms it into productivity, hence promoting technological progress. Second, it enhances the skills and competencies of workers, enabling them to perform in their workplace and adapt to meet the demands of the changing job market. In this regard Bishop, Heim & Mihaly (2009) point out that the level and distribution of educational attainment is assumed to be economically important because of two main reasons. First is the potential impact it has on the quality of service and goods and second, because of its impact on income distribution.

Over the years, educational attainment and schooling have been considered as factors that promote the flexibility of labor markets and enhance the society’s adaptability to technological, cultural, and social demands. This is the reason why many countries in the West (including Norway) have been involved in wide reformations of their educational systems. DeLaat & Sevilla-Sanz (2011) outline that the aim of such reforms is to increase the level of general knowhow while deepening vocational and technical training. This makes it very essential to prepare an increasing number of Norwegian-Pakistani women for the swiftly changing society for their participation in the labor market. However, this concern has more to it than the economic inclination of education. Bhatti & Shar (2010) outline that there is a big aspect of concern on the accessibility, accountability and quality of the education system if it were to benefit the group that is focused on in this study.

When comparing the two countries that are addressed in this study, it is important to note that Pakistan has a more traditional approach to labor division that is based on gender. In comparison, between 1980 and 2000, the gender disparity in labor participation in Norway narrowed significantly (Buligina & Sloka, 2012). However, a lot of labor assimilation has taken place. But still there are differences between the role of education in labor participation among Norwegian-Pakistani immigrant women and other women of Nordic origin. There is evidence suggesting that the country of origin determines the level and patterns of labor participation among women immigrating to Norway. However, little research has been done to determine how the Nordic social norms and conditions in the labor market influence the supply of labor among Norwegian-Pakistani women.

In addition, Naveed et al. (2011) adds that the earnings of Norwegian-Pakistani women vary depending on whether they are wage-employed or self-employed. Studies have shown that the level of earnings differs greatly between immigrants in these two categories. It is therefore probable that one way through which education raises the earnings of these female immigrants is by enabling them to get jobs in sectors and industries with a better pay.

From a policy perspective, it is very important to elucidate on the link between training and outcomes in the labor market. This study seeks to answer the question: “what is the significance of education in labor participation among Norwegian-Pakistani women?” The researcher used a qualitative research design to address this question.

Objectives of the Study

The study had several objectives. These are listed below:

- To determine how the background of Norwegian-Pakistani women and their arrival in Norway affect their labor participation.

- To determine how the Norwegian language affects labor participation among Norwegian-Pakistani women.

- To determine how the attainment of education affects labor participation among Norwegian-Pakistani women.

- To ascertain the impact of culture and tradition on participation of Norwegian-Pakistani women in the labor market.

- To find out how family patterns among Norwegian-Pakistani women influence their participation in the job market.

- To find out how the expectations of Norwegian-Pakistani women influence the education and labor participation of their own children

Research Questions

The research questions were related to the study objectives. By answering the questions, the research would have effectively addressed the objectives of the study. The research questions are as follows:

- How do the background of Norwegian-Pakistani women and their arrival in Norway affect their labor participation?

- How does the Norwegian language affect labor participation among Norwegian-Pakistani women?

- How does the attainment of education affect labor participation among Norwegian-Pakistani women?

- What is the impact of culture and tradition on participation of Norwegian-Pakistani women in the labor market?

- What is the effect of the family patterns among Norwegian-Pakistani women on their participation in the job market?

- How do the expectations of Norwegian-Pakistani women influence the education and labor participation of their own children?

Definition of Terms

- First Generation Immigrants: Those who were born in Pakistan and immigrated to Norway

- Second Generation Immigrants: Those who have at least one Pakistani parent who came to Norway as an adult

- Labor Participation: Contribution to the workforce

- Wage-employment: The kind of employment where one is salaried and receives regular remuneration

- Self-employment: The kind of employment where one pays themselves a salary

- Employability: One’s capacity to join the labor market

- Assimilation: Positive impacts on the culture of the job market in a host country and which makes one a better worker.

- Brain Drain: The negative impact that is presumed to be left on the occupational structure and national economy of the home nation after one emigrates.

Significance of the Study

European economies have experienced a great deal of technological renewal and structural change in the recent past. This has culminated in the increased awareness on the importance of human resource as a determinant of economic performance (Commonwealth Secretariat, 2007). Despite the fact that unemployment has been on the rise, there is still a huge shortage of effective training and skills among immigrant women in Europe. According to Hotchkiss et al. (2010), this inadequacy of skills has hindered participation in the labor force. In nations such as Norway, a good education has become an essential requirement for competitive participation in the labor market. This is especially important for the increasing number of female immigrants from Pakistan. The study will address this issue by analyzing how education among these women affects their participation on the labor force.

However, the practices, policies, and institutions of training and educating workers in the country may not be flawless. Yates (2011) is of the view that there may be some degree of irrelevance and inadequacy in providing effective training to female workers of Pakistani origin. In the same light, the rate of change in the technological world has rendered traditional occupational training obsolete. The situation is dire when it involves persons having a background of third world occupational training (OECD, 2011 b). The notion that one needs to undergo training first and work later without any further focus on educational training has become irrelevant. Workers are increasingly finding it important to update and upgrade their professional qualification for them to be effective in the job market.

In a nation that has a very low birth rate, the older members of the society (including immigrants) have to receive occupational re-training because the number of young people joining the labor market is very low (OECD, 2011b). There are obvious knowledge gaps on occupational qualification of the increasing number of Norwegian-Pakistani women and the economic relevance of their qualifications. This study is important as it addresses the issue of how immigrant women can be adequately trained to fit into the labor market. The study is also significant as it will come up with modules for the empowerment of these women in order to increase their contribution in the labor market.

Assumptions made in the Study

- In this study, it was assumed that education has played an important role in enhancing the participation of Norwegian-Pakistani women in the labor force.

- It was also assumed that the experiences of the Norwegian-Pakistani women can be extrapolated to represent those of other immigrant women in Norway and Europe in general.

- It was assumed that there are differences and similarities between the experiences of first generation and second generation Norwegian-Pakistani women.

- It was assumed that culture and tradition has played an important role in determining the level of labor participation among the immigrant women in focus.

- It was assumed that parents and spouses have significant influence on the labor participation of their children and partners in the future.

- This study assumed that it is important for a Norwegian Pakistani woman to receive training in the Norwegian language in order to be effective in the job market.

- This study assumed that family patterns (either extended or nuclear) have an impact on the participation of Norwegian-Pakistani women in the job market.

- The researcher assumed that the expectations of parents with regard to the educational achievements of their children are important in determining their occupational participation in the future.

- It was further assumed that the background of Norwegian-Pakistani women influences their participation in the labor market.

Scope and Limitations of the Study

Outlining the scope and limitation of the study is essential because all aspects of a given phenomenon cannot be addressed in a single document. This is the reason why the researcher had to pick one aspect of the phenomenon at hand and focus on it. This section of the report outlines the boundaries beyond which the researcher’s findings may have limited application:

- The study was limited to the impact of education on Norwegian-Pakistani women labor participation. This is in spite of the fact that the participation of these immigrant women in the labor force is affected by several other factors.

- The study was also limited to women of Pakistani descent living in Norway in spited of the fact that there are many other immigrants for example from Vietnam, Somalia and other parts of the world.

- The study did not focus on the role of education on Norwegian-Pakistani men even though they are subjected to relatively similar challenges in a foreign land.

- The study sample is made up of only six women. As such, the findings from the case studies may not adequately reflect the experience of all Norwegian-Pakistani women

- This study focused on the impact of education on labor participation in spite of the fact that education also influences other aspects of the immigrant women’s lives.

- The study only outlines the case in Norway even though Pakistani women have immigrated to other countries in the West.

- The study does not exhaustively take into account the education that is gained through informal means such the one provided in the labor market by employers although it is especially important in enhancing one’s competitiveness in labor participation.

Literature Review

Theoretical Framework

Overview

Sociologists and economists have come up with several theories to explain the role of education in social welfare and enhancement of a nation’s economic capacity. The mainstay of the argument that attainment in education has the potency to influence the output of services and goods a nation produces depends on the acceptance that schooling is one of the main ways through which people develop their workplace skills (Zhuang, 2010). A person who has more and better skills will more likely participate in production than his or her counterpart who has no such skills. In this regard, workers are expected to have a higher economic output because of their skills. The discussion outlined in this section takes into consideration both empirical evidence and alternative theories on the relationship between educational achievement and participation in labor.

Human Capital Theory

This particular theory posits that education has a direct impact on the productivity of labor and this takes place through skill creation (Zhuang, 2010). Because education culminates in skills which enhance labor productivity, it is thus a force that promotes social welfare and influences economic activity. In this case, a person views education as an investment. They are presumed to make decisions on educational attainment on the basis of the pay-off they will receive later as they pass through various educational levels.

Zhuang (2010) is of the view that this was a very common perspective in the 1950s and it was mainly promoted by the writings of Theodore W. Schultz. Later, Gary Becker built on Schultz foundation and pointed out that wage differences on the basis of educational levels were quite evident in the society and this was indicative of the manner that education contributes to productivity in the society (Rebecc, Sheldon & Robert, 2008). This theory posits that educational input is productive and the marginal contribution thereof can be easily approximated by differences in the wages between the educated and the uneducated. According to Rebecc et al. (2008), this view is founded on the precept that for the educated, the labor market operates through competitive economic analysis.

Sorting-Screening Theory

Yates (2011) is of the view that in the 1960s, the human capital perspective was subjected to diverse criticisms. This is on the link between labor productivity and educational attainment and how education results in social welfare and economic activity. Some of the critics regarded education to be a mechanism for labor force sorting and screening. This theory suggests that employers favor their more educated employees not because they are more productive on the job but because they believe that the system of education has a way of selecting innately productive individuals. This implies that the main role of education is to sort workers based on innate productivity as opposed to enhancing productivity (Zhuang, 2010).

The purest version of this theory suggests that going through the education system provides information on a person’s pre-existing behavioral traits and aptitudes. These traits and aptitudes are assumed to culminate in labor productivity as opposed to psycho-motor skills and cognitive development that one gains in school. This perspective outlines that education is not a skill-producer but an information-generator. The question is whether apart from going to school there could be another socially cheaper mechanism that could be used to generate the information. There are some versions of this theory that believe in education’s role to develop cognitive and psycho-motor skills (Rebecc et al., 2008).

Socialization

This theory outlines that education is more of a tool that is used to come up with social strata. It is founded on the works of Bowles and Gintis published in 1975. In this case, the employer requires more educated workers because they expect them to have a better social orientation with regard to the job environment. Because of this orientation, their level of work- setting productivity is higher (Zhuang, 2010). There is a dual explanation for this. First, it postulates that people learn diverse social attitudes at school and these attitudes are strengthened as they pursue more education. In the second explanation, these attitudes are not “taught” but “caught” in the educational system. The school separates individuals according to their social attitudes. Only those with the desirable set attitudes manage to move higher on the educational ladder (Rebecc et al., 2008).

According to socialization, there are certain social traits that create the distinction between the educationally successful and educationally unsuccessful at the lower schooling levels. These are compliance, docility, concentration, persistence, punctuality, and team work. At the higher school levels and at work the social traits that are required for success are leadership, versatility, self-reliance, and self-esteem. Just like the sorting-screening theory, this theory points out that schools were not meant to develop the psycho-motor cognitive skills of students. The stronger versions of this perspective outline that schools are there to promote capitalism and thus institute the division of labor. The division is heightened by mobility barriers that exist in the market (Yates, 2011).

Significance of Education in Women’s Global Labor Participation

Overview

Many studies have indicated that in both developing and transitional economies, women get more economic returns from education than men (Syed et al., 2006). In these countries, the only level where men have more economic gains from education than women is in the transition from total ignorance to primary school level education. When women complete secondary education, they have more gains in terms of wages than men. One study that was conducted in 2010 in the Philippines found out that formal education is the main determinant of a person’s wage. The study identified that formal education has a 37 per cent contribution to a woman’s wage and a 24 per cent contribution to a man’s wage (Rezai-Rashti, 2011). There are various possible reasons for such an observation. It can either be as a result of the distribution of jobs in accordance to the level of education and because of the lesser discrimination on the basis of gender when it comes to jobs that require one to have completed secondary level education. According to Sigurd (2008), a 2007 government report outlined that one of the main factors that led to the increase in real wages for women in Bangladesh between 2000 and 2005 was the increasing number of workers who have some form of secondary education.

Moreover, when compared to the past, global trends are contributing to an increase in secondary and post-secondary education returns. Syed et al. (2006) notes that there may be many factors that are in play such as the shift in educational attainment distribution, the change in the international markets that has been brought about by market liberalization, growing international trade, and the declining quality of primary level education because of the global emphasis on eradicating illiteracy. Rezai-Rashti (2011) outlines that the most important observation is that girls in many developing nations begin to reap the benefits of going to school only after completing secondary school while boys may have economic opportunities with primary school education.

It is most interesting to note that there is little research that has been done to find out whether there is a difference in terms of economic opportunities for persons who have completed secondary school only and those who have completed vocational secondary school. Okamura & Islam (2011) point out that in spite of the fact that they are costly and many researchers doubt their effectiveness, many nations still have vocational secondary school programs. Students who do not perform very well at primary level are sent to vocational or technical schools. Although those who join the general secondary schools go through a curriculum that prepares them for tertiary level education, it is in most cases very abstract and just academic. The curriculum of vocational secondary school on the other hand is inferior.

Leonesio, Bridges, Gesumaria & Bene (2012) outline that women and men choose different majors in technical schools which in essence is reflective of the norms in the society regarding gender roles. For instance in Indonesia, 65 per cent of male students in technical secondary schools choose an industrial major while 56 per cent of their lady counterparts take business management and 29 per cent tourism. Female graduates in vocational secondary schools in Indonesia seem to have higher wages than their colleagues from the general secondary schools. Leonesio et al. (2012) point out that in Indonesia, the wage premium for men who have been through technical school has being reducing while that of women who are more than 30 years old and have been through technical school has being increasing. It is seems that this difference is driven by the fact that the service industry in the country has being growing and thus the tourism and business management sectors are absorbing more female vocational school graduates. The economic changes in Indonesia that are being driven by the nation’s response to worldwide demand have created more opportunities and an encouraging environment for women who have graduated from vocational schools.

Mahoney (2010) is of the view that school quality is also an important aspect when it comes to the translation of years of schooling into gains in the labor market. Many studies have found out that the rate of school dropout among girls is high in schools which have poor learning outcomes. It is noted that when girls join schools that provide quality education, they have a rapid transition into the job market. Mahoney (2010) is of the opinion that this is particularly the case in settings with a high rate of unemployment.

Skill relevance is also a factor that is very important in determining the economic value of education. For instance, a study that was conducted in Brazil in 2010 found that women who had graduated from secondary school but were fluent in at least one international language earned better wages than some graduates who were only fluent in a local dialect. Another study that was conducted in Senegal also found out that women who are fluent in French had better employment opportunities in the country’s formal sector (Mahoney, 2010).

Alternative Strategies

Khan & Khan (2009) notes that because of the challenges that are facing women with regard to educational access and labor participation, governments have come up with diverse approaches to address them. Some of these approaches are within the system of education while others are without. They are geared towards addressing the growing global aspirations for education and remunerative work among women.

Some governments have come up with non-formal alternatives for girls who either dropped out of school or did not have access to formal education in the first place. The programs are not aimed at getting the girls back to the formal system but to provide them with marketable skills. However, there are some governments which have integrated these programs into their formal systems. In West African countries, these programs have been implemented to assist girls who did not finish schooling because of civil wars (Khan & Khan, 2009).

Currently, there is no data that documents the extent of coverage and effectiveness of these programs but most sources have it that the enrolment is considerable. Khan & Khan (2009) points out that there are two reasons for this informational gap; 1) the phenomenon is quite new and 2) it is not easy to gather information on participation in educational systems without referring to levels and grades. Additionally, the programs are yet to be evaluated on the basis of outcomes and transition into the job market. In this regard, it cannot be concluded that they have played a part in enhancing women labor participation.

There are alternative formal programs that have been put in place to help girls who have not been able to access formal education. The first action has always been to provide in-kind subsidies and cash to allow them to join general secondary school and also expand the reach of secondary education. The main objective of such programs is to expand education demand rather than focusing on the school quality issues at the classroom, school or education system level. The approach is justified by the fact that education has been associated with poverty alleviation and economic empowerment in developing and transition economies (Khan & Khan, 2009).

Formal Support Programs

There have also been endeavors to create an environment that supports girl education within the formal setting. Hotchkiss (2005) notes that this is mainly by training and hiring female teachers, offering educators courses on gender training and offering after- school programs such as tutoring and mentoring support. This is geared towards the creation of a protective and supportive learning environment for young girls. According to Hotchkiss (2009), another approach has been to put in place. This is a curriculum that teaches girls how to develop marketable skills like math, science, fluency in international languages, and computer literacy. This is an approach that focuses on the formulation of a relevant curriculum in the sense that it corresponds to the demand in the market and teaches remunerative skills. These approaches include school quality aspects that are definitely beneficial.

Incentives

DeLaat & Sevilla-Sanz (2011) posits two researchers (namely Lloyd and Young) conducted a study on 320 programs that were intended to enhance the girl education. The two document that 45 per cent of the programs included some way (either financial or in-kind contribution) to incentivize school attendance among teenage girls. This has been proven through quasi-experimental or randomized impact evaluations to be effective in encouraging girls to pursue formal education up to the point they have garnered sufficient skills to earn them jobs. However, DeLaat & Sevilla-Sanz (2011) also outline that there are issues of cost-effectiveness and targeting in this approach.

The classic example is the secondary school sponsorship program that was put in place in Bangladesh in 2005 to support girl education. According to DeLaat & Sevilla-Sanz (2011), the program has been very effective because it has reversed the gender gap in Bangladeshi secondary school level education. This was made possible when the government decided to modernize Madrasa schools to teach secular subjects. The result was that many girls enrolled in these madrasas that were recognized by the government. It has however not yet been established whether the learning outcomes and economic benefits of being in the modernized madrasa and those of being in a secondary school classroom are similar. Another example outlined by DeLaat & Sevilla-Sanz (2011) is the program by the government of Japan to sponsor girls in Cambodia to finish their primary school level education.

Significance of Education in Norwegian-Pakistani Women’s Global Labor Participation

Various studies have been conducted to determine how educational attainment has influenced the lives of female immigrants in Norway. Most of the studies have concluded that the attainment of education increases the likelihood of these women either being self or wage employed. Kristin (2011) points out that although age is a very important factor that determines whether Norwegian-Pakistani men get absorbed into the workforce, for women it is not such a fundamental factor. The reason is that the average Norwegian-Pakistani woman has a 30 per cent opportunity of getting wage-employed in her life.

For instance, a 2005 study revealed that the likelihood of male Pakistani immigrants being wage-employed increases sharply if they have attended school for at least five years. However, in the case of women, their chance of getting employed is higher if they have spent at least 10 years in school (OECD, 2011a). Most studies conducted in the past however confirm that female immigrants from Pakistan who have attended secondary school have a higher chance of participating in the labor force. As these women grow older (beyond 30 years of age), their likelihood of being employed also increases. Numeracy and literacy have marginal impacts on job outcomes because they promote the entry of Norwegian-Pakistani women into the labor market through self-employment or wage-employment (OECD, 2011b).

As the rate of immigration into Norway increases, the country continues to record an increase in the rate of employment growth. From 1995 to 2008, Norway has been rated second after Spain for the highest employment growth rate (UNDESA, 2010). Within this period, the number of employed persons has increased by 100 per cent. Most of these new jobs are in sectors with low productivity such as consumer services and construction where most immigrants have had the opportunity to find wage-employment. In the light of other changes in the professional structure, the growth has been at both ends of the ladder.

The country has experienced expansion in the consumer and construction sector (on the lower end) and the sectors that require professional training that comes from having at least a bachelor’s degree (on the upper end) (OECD, 2011a). Within the same period of time, the number of employment opportunities in the service and manufacturing sectors has declined, albeit slightly. This implies that Norwegian-Pakistani women- most of who fit at the lower end of the occupational structure- have more opportunities to participate in the labor market. Nonetheless, these women do not have sufficient opportunity to advance their careers in the low end occupations. That would require them to have professional training that would qualify them for skilled non-manual jobs.

Moreover, Bishop et al. (2009) point out that when the level of education among the Norwegian-Pakistani women is compared to that of native Norwegian women, the former are sparsely represented among those who have received tertiary education. This also appears to be the case when they are compared to their counterparts from other regions of the European Union, Eastern Europe and the United States. However, they perform better on the education front than immigrant women from Africa. For example, 15 per cent of all female immigrants from Morocco who live in Norway are illiterate (Grete & Anniken, 2012).

The incidence of occupational inactivity among immigrant women in comparison to the Nordic population is lowest for women from Eastern Europe and highest for those from Africa (Cebula & Coombs, 2008). The inactivity incidence among Norwegian-Pakistani women is estimated to be 21 per cent. Norwegian women with double nationality or those who were born abroad have higher labor participation than their native counterparts. Just like in the case of male immigrants from Pakistan and all over the world, immigrant women are more likely to be unemployed than native Norwegian women. This disadvantage is however more severe for women from African countries. African women have a risk of unemployment that is at least twice that of native Norwegian women (Grete & Anniken, 2012).

Male and female immigrants from all regions are mainly concentrated in unskilled labor sectors (Buligina & Sloka, 2012). It is important to outline the fact that when compared to their native counterpart, Norwegian-Pakistani women are over-represented in unskilled labor and under-represented in skilled occupations. A large number of women immigrants from Pakistan are mainly involved in taking care of dependants and cleaning (both falling under consumer services sector). When these jobs are compared to those of male immigrants from Pakistan- mainly in the manufacturing and construction sectors- they present few opportunities for career development and upward mobility. Immigrant women from Pakistan, just like other immigrants, are involved in small businesses that have been essential in taking them from the lower end of the occupational structure. Most of their businesses are either sole proprietorships or small companies with up to five employees. The form of businesses operated by these women ranges from corner shops, small import-export firms and restaurants (Buligina & Sloka, 2012).

Education and the time that one has spent in the country is an important determinant of whether they will be employed or unemployed. For female immigrant from the European Union and OECD countries, the returns are comparable to those of native countrymen. The more educated a person is, the more the probability of being employed. Women from Pakistan who have a bachelor’s degree have close to 2 per cent advantage over those who have attained secondary school level education only. Of most importance is that those who are illiterate find it extremely difficult to secure employment in the nation (OECD, 2011). However, there seems not to be an educational advantage for immigrants from some Asian and African nations. The reason is that female immigrants who came into the country with lower educational attainments seem to get jobs faster than those with university degrees. This phenomenon can be attributed to the difference in curricula and labor market dimensions between Norway and most Asian and African countries. Nonetheless, Norwegian-Pakistani women who received educational training in any European Union country or in the United States have at least a 23 per cent labor participation advantage over their counterparts who schooled in Pakistan.

Benito & Bunn (2011) outlines that regarding the time of stay in Norway, the general observation is that the longer Norwegian-Pakistani women stay in the country, the more likely they are to be absorbed into the job market. However, studies have indicated that this is only the case up to the first five years beyond which there is no empirical evidence to support the presumption (Franci et al., 2012). This phenomenon has been observed among all immigrants apart from those coming from Europe whose likelihood of being employed is not necessarily determined by how long they stay in the country. When all other factors are taken to be a constant, it has been observed that differences in occupational activity between native women and Norwegian-Pakistani women reduce with the passing of time (Franci et al., 2012).

Women from other European regions and who possess a university degree have a higher chance of getting employed. These trends of employment with regard to the time they come into the country are quite complex (Buligina & Sloka, 2012). Their chances of being employed are either very high immediately they come into the country (mainly because they come to Norway after receiving a job offer) or after their second year of stay. This displays a rather gradual but steady rate of integration into the job market, maybe because of their patience as they wait for a job offer. On the other hand, the employability of Norwegian-Pakistani women is highest after the first three years of stay.

It has also been observed that Norwegian-Pakistani women who live with their young ones are less likely to participate in the labor market as compared to their native counterparts or those from EU. The main reason is that it is very difficult for them to reconcile child care with work as long as they are in paid employment. This is largely because of the limitations of services that deal with public care in the country and the high cost of private child care. Additionally, these women- unlike the natives- do not have relatives they can leave the children with. However, this may also be as a result of differences in cultures with regard to gender roles in the society (Cebula & Coombs, 2008).

Important Factors for the Norwegian-Pakistani Women’s Labor Participation

Naveed et al. (2011) are of the view that there are various factors which affect labor participation among immigrant women from Pakistan. Some of these factors are those that determine the quality and value of human capital with respect to prior educational background. These include the resources that an individual has spent in garnering educational capacity and their fluency in an international language. This is especially English which is spoken by at least 89 per cent of Norwegians today. This is together with Nynorsk which is the official language in Norway. The increasing number of English speakers in Norway is one of the reasons why immigrants from former British colonies like Pakistan, Nigeria, South Africa, and India tend to remarkably participate in the country’s labor market in spite of their lack of fluency in Nynorsk.

In addition to the above mentioned factors, Benito & Bunn (2011) note that there are also cultural and social factors which influence the trade-offs that Norwegian-Pakistani women make between household responsibilities and participating in the labor market. The factors that affect the participation in the job market are to some extent determined by the reason why they migrated in the first place. In this regard, immigrant Norwegian-Pakistani women can be classified into two. These are those who migrated to join their families, especially their husbands, and those who migrated in pursuit of educational and occupational opportunities (Hotchkiss, 2005). The performance and participation levels in the labor market among these two categories of women are quite different even though human capital attributes such as the level of education may be similar. Other factors that differentiate “accompanying” Norwegian-Pakistani migrants from “economic” immigrants may include where they acquired education, their husband’s nationality, number of their children, and marital status among others (Grete & Anniken, 2012).

The level of employability among Norwegian-Pakistani women in Norway is relatively low when compared to that in Pakistan. In this regard, the skills of these women are obviously underutilized. This indicates human capital misallocation in Norway. However, the low participation level may also be as a result of personal and cultural preferences rather than discrimination and constraints in the labor market. Additionally, another factor that is responsible for the low participation level is the fact that the performance of immigrant women from developing countries in the labor market is low. These variations are either measured by the kind of job that they find or their wages. The variation can be attributed to the low quality of education in Pakistan and other developing and transition economies in addition to other factors which influence human capital acquisition before migration (Amuedo-Dorantes & Grossbard, 2007).

Bishop et al. (2009) posit that the factors that affect the participation in labor among Norwegian-Pakistani women have been studied in relation to the theories of assimilation or brain drain. A lot of the literature on assimilation outlines that the level of earnings is the main measure of immigrant worker performance and participation. However, the level of a person’s earnings do not reveal what they are actually doing in the country they have immigrated to even though they determine one’s occupational choice. Because there is a concern on creating and allocating human capital, it is thus important to consider the types of jobs for highly educated female immigrants from Pakistan. Bhatti & Shar (2010) outline that that the extent to which the similarity between the home country and Norway’s laws of immigration have a notable impact on immigrant’s quality distribution. However, the research has not focused on the relationship between immigration behavior and home country characteristics.

Some authors have emphasized on migration pattern selection biases which result from differences in income distribution patterns at home and in Norway (Hotchkiss et al., 2010). According to this approach, the differences between the earnings of Norwegian-Pakistan female professionals with similar academic qualifications can be attributed to the economic and political differences between Pakistan and Norway. This is the reason why female immigrants from other European countries easily participate in the Norwegian labor market. Other studies have found out that there is little empirical evidence on the under-representation of these women in skilled occupations in comparison to native Norwegians who have the same experience and educational training. One of the reasons is that the immigration policy in Norway calls for the screening of the immigrants on the basis of their educational background (Scott et al., 2010).

These studies do not relate differences in labor participation to attributes of the home country but rather on differences that are based on linguistic fluency. A different study that was conducted in Canada and Israel (two nations that have experienced increased entry of skilled female immigrants) found out that there is an essential attribute of imperfect portability that links a person’s performance in another country’s labor market to their home country attributes (OECD, 2011b). Another study found out that the earnings of a skilled immigrant worker from Asia are usually the same as those of native professionals at the time they are coming into Norway. But with time, there tends to be a decrease. The explanation of this observation is dubbed the “family investment tactic”.

This is a strategy whereby the woman works very hard at the beginning in order to support the investment of the husband in marketable skills. Later on, husbands are assimilated into the Norwegian labor market and subsequently earn higher wages which culminates into less work for women. These findings have been supported by other authors who outline that for the first ten years, assimilation effects are responsible for the higher rates of labor participation among Asian immigrants (Leonesio et al., 2012). Others have analyzed the impact of children on the supply of labor among immigrant women in Norway and have found out that the child-status-work relations are similar for natives and immigrants. The issue of selectivity among female Norwegian immigrants has also been studied but rather narrowly. The findings have confirmed that women who come from richer countries perform better with respect to labor participation in Norway, just like men (Scott et al., 2010).

The other essential issue that determines labor participation among Norwegian-Pakistani women is brain drain. This has to do with the negative effects that emigration of professionals have on their developing home countries. The concern is mainly because the expatriation of the labor force leads to a reduction in the positive externalities which are generated by the elite in the economy and loss in educational investment tax revenue (Nanc, 2005). However, some studies have highlighted that with time, the source nations benefit from knowledge and information flow, migrant networks, resource repatriation, and return migration. Such benefits depend on the performance of migrants in the labor market of the host country. Further studies have however pointed out that brain drain should be measured with reference to human capital quality as opposed to the number of migrants (UNDESA, 2010).

The place from where a person obtained their education is an important determinant of how they participate in the labor market. It is also an important aspect in assimilation literature. The 2006 census in Norway is an exceptional source of information on the important factors for labor participation among immigrants (Commonwealth Secretariat, 2007). However, it does not have information on where a person received their education from. In this case, studies regard Norwegian-Pakistani women as “Norway-educated” if they arrived in the country before having attained the age that they would have normally completed the level of education declared. For example, a woman who came to Norway from Pakistan at 23 years of age and declared that she had a university degree is normally regarded as having been “foreign educated”. According to the information that was gathered during the census, 69 per cent of all immigrant women from Pakistan completed their education (either secondary or tertiary) after arriving in Norway (Kristin, 2011). This finding is reflective of the fact that many families immigrate into the country with their children who later receive Norwegian education.

According to Benito & Bunn (2011), the level of education for “Pakistani educated” women differs for two main reasons. First, the average level of education for women who received their education from Pakistan differs. Second, the women are drawn from rather disproportionately diverse segments of the Pakistani educational spectrum. Benito & Bunn (2011) continue to say that on average, Norwegian-Pakistani women have attained a higher level of education than their counterparts in Pakistan. In contrast, female immigrants from Latin American and developed western countries have a lower educational level than their counterparts at home.

Such findings strengthen the perspective that immigrants should not be regarded as random samples of the population of their home countries. Additionally, there are other selection issues with Norwegian-Pakistani women. Naveed et al. (2011) indicates that many of them migrate with their families or join their families later on after the migration of the husbands and they may not have plans to join the labor market but rather to maintain their households. In this case, their level of education may not affect their labor participation. However, there are many Norwegian-Pakistani women who immigrated into Norway in pursuit of a better education and better paying jobs.

The Comparisons between First and Second Generation Norwegian-Pakistani Women’s Labor Participation

Available literature makes it clear that second generation Norwegian-Pakistani women have a higher level of labor participation than their first generation counterparts. The rate of labor participation among second generation Norwegian-Pakistani women has actually been on the rise since the year 2000 (Cebula & Coombs, 2008). One particular study that was conducted in a sample from Oslo and surrounding areas in 2004 found that the second generation immigrants scored 23 percentage points higher than the first generation immigrants when it comes to absorption into formal employment (Grete & Anniken, 2012). Some researchers contend that the first two groups to immigrate belong to the first generation while others posit that the subsequent two groups constitute the second generation (Nanc, 2005). This study opts for the latter approach because the second two groups have more similarities between themselves than they have with their parents. These similarities are in terms of culture and occupational training (Mahoney, 2010).

In terms of labor experience, the subsequent two groups are quite different from the first group that came to Norway from Pakistan. One study found that the second generation of Norwegian-Pakistani women has a labor participation rate that is close to that of native Norwegians (Buligina & Sloka, 2012). However, it is better to make inferences in the long term as opposed to using data that was collected and analyzed during the first few years of arrival for such a comparison (Zhuang, 2010). In this regard, one study compared the labor participation among the various generations of Norwegian-Pakistani women who arrived in Norway aged less than 12 years and those that were older than 12 years.

The younger generation had a labor participation level of 54 per cent while the older generation had a labor participation level of 13 per cent (Buligina & Sloka, 2012). The logical explanation is that the older ones face more hurdles when joining the workforce and a large number of them work for some time and retire to take care of their families. Moreover, a significant proportion of these women never join the Norwegian workforce (Rebecc et al., 2008). On the contrary, the younger women join Norwegian educational system and are later absorbed into the job market having credentials and a linguistic background that is similar to those of the natives. The second generation women are not largely affected by retrogressive cultural beliefs, especially those concerning societal gender roles (Cebula & Coombs, 2008).

Another study compared the participation of the female immigrants from Pakistan who came into the country in 1996 with those who had come earlier. The results showed that the women who had stayed longer in the country had a higher level of labor participation than those who had arrived much later (Cebula & Coombs, 2008). However, the rate of participation for both of them was far much lower than that of the natives. The results of the study were quite complex because for the Europeans who arrived in the country at the same time, the rate of participation was higher than for those who came in later (Yates, 2011). The study found that with time, the rate of participation in the Norwegian labor market for Norwegian-Pakistani women becomes similar to that of their native counterparts. However, the rate of labor participation for the second generation is higher and some researchers suggest that at some point, it converges with that of the natives (Buligina & Sloka, 2012).

Research Methodology

Research Strategy

Various authorities in the field of research and data analysis provide both a general and specific definition of a research design. According to Creswell (2009), a general research design refers to all the issues involved in the planning and execution of a research project. This is from problem identification to the publishing of results. He adds that more specifically, research design is defined as the process through which a project rules out and guards against alternative interpretation of results (Creswell, 2009). The discussion that is presented in this section of this study aims at reducing the possibility of multiple explanations of the findings provided in the next chapter. For this particular project, the researcher opted to use a qualitative approach.

Method Choice: Qualitative Case Study

It is quite hard to settle for a particular method while conducting a qualitative research. This presumption is shared by Strauss & Corbin (1990) who posit that the complexity is brought about by the diversity of arguments for and against different methodologies. The researcher chose to use the case study method for this particular research.

Before justifying the selected method, it is important to outline what a case study is and what it entails. Zikmund (2010) defines a case study as a confined system which can be a person, a process, an event, an organization, a location or even a time in history. Other authors have added that a case study can include a process or a product. A case study is a strategy in research that tries to comprehend dynamics in a single setting. Creswell (2009) provided a two-fold technical and operational definition of what a case study is. According to him,

- A case study is a method of investigating the depth of contemporary phenomenon in a real life situation where the line between context and phenomenon is not clearly distinguishable.

- A case study deals with a situation that may have more variables than numerical data points where a single finding comes from diverse sources and data has to triangulate. This is where the next finding benefits from prior propositions so as to guide the collection and later the analysis of data.

According to the above mentioned definitions, it is clear that the case study methodology is the most preferable choice when providing answers to “how” and “why” questions like it is the case in this project. The definition depicts that a case study is important for a researcher who wants to come up with an in-depth understanding of an event, a person, situation, group or social setting and how it relates with the surrounding and the outcomes derived from the interaction.

The selection of the case study method for this project is justified by the reasons outlined below:

- By using this method, it is possible to triangulate qualitative data and techniques of data collection. It can be used with data that has been collected through observation, qualitative interviews, surveys, and from archives (Creswell, 2009).

- According to Denzin & Lincoln (2005), authors in developmental studies have recommended the use of case studies. These authors propose that a case-comparative and developmental approach should be used when studying an area in developmental studies, where the issue of labor participation among women in this study falls. Empowering immigrant women to participate in the labor market is reflective of a reality that is socially constructed and one that should be comprehended in its right social context. In this case, the project at hand emphasizes the use of case studies.

- Developmental areas such as labor participation among immigrant women in Norway have not been adequately studied. In this regard, there is a need to generate knowledge that can be used for description, testing, and theory generation.

- The study at hand is multi-disciplinary in nature because it includes understanding concepts of mature disciplines such as politics, developmental economics, psychology, and sociology.

- A case study is best used when the researcher is focusing on a contemporary situation that cannot be easily separated from its context. The issue at hand has strong similarities with this proposition of phenomenon and context.

- The case study method is beyond the debates of qualitative and quantitative research methods and as such it can be used in both methods. Many researchers in the social disciplines have outlined that the quantitative method does not suffice for all research problems.

According to suggestions provided by a variety of literature, case study is a method that can be used while employing various techniques. Instead of eliminating these alternative techniques, a case study integrates them and uses them to get the best out of a research problem. Bailin & Grafstein (2010) outline that case studies are comprehensive enough to involve at least six techniques used to source for evidence. These are physical artifacts, participant-observation, direct observation, interviews, archival records, and documentations. The authors note that these are the main techniques that are used in case studies. But they add that other researchers find case studies to be comprehensive enough to integrate techniques such as life histories, kinesics, psychological testing, “street” ethnography, and proxemics.

The above noted techniques have their own demerits and that is why it is essential to use them under a research method such as a case study. Therefore, the researcher capitalizes on the strengths keeping the project far from the limitations of the technique used.

Using the case study method, the researcher interviewed six Norwegian-Pakistani women. The main technique that was used is qualitative interviewing along with the review of past literature.

Study Technique: Semi-Structured Interviews

The researcher chose to use semi-structured interviews in this project. This technique was chosen because of various reasons. These are listed below:

- Just like conducting a survey, a structured interview would provide information with limited depth than the researcher needed to develop an insight on labor participation of Norwegian-Pakistani women.

- On the other hand, an unstructured interview would not be a preferable choice because it would result in a discussion storm from which it may be very difficult to extract beneficial information.

Interviewing Technique

In the course of data collection, the researcher used a non-directive approach where they posed a question to the respondent and allowed them to respond with an explanation. As the respondent continued to give her answer, the researcher would pick the keywords that needed reflection from the discussion. However, the researcher tried as much as possible to stick to the set of questions in the guideline and thus was able to strike a balance between the non-directive and directive approaches.

Interview Setting

The researcher opted for personal face-to-face interviews in the natural setting of the respondents’ offices or homes. With the exception of a ringing mobile phone from one or two respondents, there was barely any disturbance during the course of the interviews. The objective of this study was to find out the role that education has played in empowering Pakistani women living in Norway to participate in the labor market. In this sense, personal interviews were important to establish the status of women in Norway. This kind of an interview provided the researcher with primary information. Moreover, it was possible to find case studies that specifically address this research problem.

Why Face-to-Face Interview?

In this era of technological advancement- especially in the area of social networking- some people have the feeling that conducting physical interviews may be wastage of time and resources. However, in spite of the financial challenges, the researcher decided to use face-to-face interviews in order to understand and appreciate the experience of the respondents. This would not have been achieved if the researcher had chosen to use Facebook video or Skype. However, the researcher was of the opinion that he would use Skype in case some of the respondents were unreachable, but the face-to-face remained the technique of choice. Only one of the respondents who were unwell was interviewed on Skype.

Interview Guideline

The guideline that was used during the interviews was composed of 43 questions. These were formulated from the review of literature on the role of education in women’s labor participation. The questions were categorized into six groups (refer to a copy of the interview schedule in the appendix section). These are follows:

- Background and arrival in Norway

- Culture and tradition

- Family Pattern

- Education and job

- The Norwegian language

- Expectations for their own children

The main considerations in coming up with the guideline included time, respondents’ convenience and focal discussion points. Each of the respondents was interviewed in one 2-hours session. It had been suggested that each interview session was going to take at least 120 minutes and none of the sessions went beyond the allocated time.

Critical Methodological Issues

The following are some of the critical issues in this methodology adopted for the current study:

Accessing the Respondents

The aim of the researcher was to find Norwegian-Pakistani women who could provide essential information with regard to the set guideline and the research problem. The women had to be willing to work with the researcher and easily accessible (allocating two hours of their time for the interview session). This was the assumption of the researcher before embarking on the project. But later it emerged that it was a false assumption because it took 3 months of preparation before beginning the sessions of face-to-face interviews. The process of accessing the women can be divided into four phases. These are as follows:

- Phase I: This process began when a Norwegian-Pakistan elite woman came to launch a book at Nordland University late 2011. A friend of mine had attended the ceremony and he later shared the information with me because he knew my interest in this research. Later, I communicated with her and gave her my background and the reason why I was interested in conducting a research on labor participation among Norwegian-Pakistani women. I asked her to assist me in finding Norwegian-Pakistani women who could assist me in gathering information for my study.

- Phase II: Afterwards, the lead gave me contacts of some women who could assist me with my project. I started communicating with them over e-mail to request for their cooperation. This was to find out whether they could find some time for the interview sessions. I began with eight prospective ladies but half of them were not available on the dates I was going to Oslo to conduct the interviews. I remained with four who were not enough for my study.

- Phase III: I decided to use the ones who had confirmed to find other two women who would form my set of interviewees. I visited the Facebook pages of the four and found some women whose input I thought would be beneficial in this project. I managed to get four women and added them to my list of respondents. One of the women had been coordinating social welfare issues among Norwegian-Pakistani women.

- Phase IV: I managed to contact them through e-mail and telephone and two of them agreed to provide me with their personal information during my visit to Oslo. In total, I managed to find six women whom I would interview using open-ended questions to find out the role of education in their labor participation.

Limitations of Research Technique

When using interviews, it is not possible to establish the reliability and validity before starting a project. This is unlike in the case of a questionnaire. This is a big problem for researchers who prefer to use the quantitative research method in social studies. Nonetheless, the researcher was able to overcome the challenge by using two approaches. First, the researcher endeavored to ground the guideline of the interview into available literature on labor participation. The researcher took time to read on the global trends and how immigrant women have being participating in the labor markets of various countries and the challenges thereof. The researcher also worked hand in hand with his supervisor who was very helpful in formulating the guideline.

Sample Selection

The objective of the study was to find out how the attainment of education has influenced labor participation of both first and second generation Norwegian-Pakistani women. The reason why it was very important to include both of these generations is that their motivations are quite different. The first generation women came to Norway either because of their families that were living in the country or because of an economic pursuit. At the time when the first generation was arriving in Norway, there were few or no efforts at all to empower Norwegian-Pakistani women both educationally and occupationally.

Immigration into Norway has been on the rise amidst changes in global trends. In this light, it would be very essential to include women from both generations in order to come up with representative findings and also to estimate trans-generational improvement. Four of the women interviewed were first generation while two were second generation ladies. It was necessary to find some women who had “Pakistani” educational training and others who had “Norwegian” educational training. This would be very helpful in determining how the two formal systems of education reflect on the benefits of educational training.

Research Quality: Reliability and Viability

The quality of research refers to the reliability and validity of the study. This term is more common in quantitative research which involves the analysis of data points to derive statistical meaning and implication. Nevertheless, the criteria to determine the quality of qualitative research are different.

The validity of research simply refers to the effectiveness of the research technique or research instrument in measuring a phenomenon. In the case of the current study, the research instrument was an interview guideline. The interview guideline may not be comparable to the use of a structured questionnaire. But when it is well grounded on available literature, it may be more effective. This is why the researcher took time to extensively study how education has assisted women to take on active positions in the labor market before they went into the field. After the study and wide consultation with the project supervisor, the researcher was able to come up with an interview guideline that was composed of 43 questions, thus ensuring the validity of the technique.

While conducting a quantitative research, it is possible to isolate findings and conduct analysis. A qualitative study such as the one at hand is driven by the researcher’s greater involvement as a person. In this regard, the interpretation of data is carried out while treating the findings as an extension of the person(s) who is doing the project. In this particular study, the researcher did his best to present the voice of the data as opposed to presenting his interpretation on the basis of his perspective. However, it is not possible to assert that he was absolutely successful in this. This implies that if another person conducted the research using the same research technique, they would arrive at related (perhaps not similar) conclusions.

Field Experience

I was in Oslo on the 20th, 21st and 22nd of February 2012 to conduct the interviews. On the basis of my experience in the field, I concluded that when collecting information from respondents, it is good to always anticipate the unexpected and not to be too certain about anything. In my case, inconveniencies ranged from taxi drivers and traffic levels to weather conditions. There are many variables that affected my initial plan, but all the same, I was able to achieve at least 80 per cent success with my target respondents.

February 20th

My first interview was scheduled for 13:00 hours on the 20th of February. Prior to the interview, I was staying at a friend of mine in Bodo. I had planned to take the flight to Oslo at 10:30 hours. It would take me around 1 hour 20 minutes to reach my destination and 1 hour 30 minutes to meet my respondent. However, because of some technicalities, the flight was delayed for 45 minutes. This meant that I only had 45 minutes to locate my first respondent and I really wanted to be on time during this first interview. However, the flight totally threw me out of plan because it took 15 more minutes to reach Oslo. I called the respondent, explained the situation to her and inquired whether it would be possible to meet her for the interview at some other time within the next three days. Though she was not working, she was quite busy and had forgotten about our appointment. She remembered and allowed me to see her the following day.

I almost lost the chance to interview her but fortunately, I got her on board and I thought to myself that everything else was now fine. That was not to be; not at all. I went to meet with the second respondent and so I asked the lady at the reception to call her for me. She first enquired whether I had an appointment and after confirming, she wanted to see it. Unfortunately, I had not carried a copy of our conversation and so I told her that we had communicated via e-mail. She went into the office and after two minutes she came back and told me that the woman I wanted to meet was not in. She offered to request someone else in the organization to assist me but I told her that it was a research and so only the predefined respondent could offer me the needed assistance. Some few minutes later, I got to know that the respondent I wanted had sustained minor injuries after being involved in an automobile accident and was recuperating from home. They declined to give me her number but I gave them mine and told them to request the target respondent to call me. This was another big disappointment for me. The respondent called me half an hour later and explained her situation to me and asked whether I could interview her on Skype, which I accepted because it was cheaper than talking on phone.

February 21st

The next day at around 06:15 hours, the taxi driver picked me from my hotel and took me to meet my third respondent. I met her at her home in the outskirts of Oslo and the two of us had sufficient time together. The interview lasted for an hour and the day could not have started in a better way. The next respondent was the one I had missed the previous day because of the delay in my flight. She had worked as a journalist but she left employment after getting a child. She was quite strict about the time I had requested and I stuck to it. The day had been quite successful and I only had one more day to interview the remaining respondents.

February 22nd

I misplaced the keys of the room I was staying in and wasted about 10 minutes trying to figure out where I had placed them. I found them in my shoe and took off for the next interview. The next lady was a first generation woman and she had come into the country together with her husband. I had included her in the set of respondents because she had worked hard to empower immigrant women from Pakistan. I arrived half an hour late but I found her in bed because she had just arrived in the morning after checking on her sick daughter at the hospital. At the time of the interview, she was in her official leave from work. The interview was most informative because it gave me an opportunity to know the real challenges that the Norwegian-Pakistanis were facing in Norway.

I met my next respondent at a restaurant in spite of my suggestions to find a serene location. There were some unavoidable irritants but the interview was very helpful. She was a writer who had offered lectures in several institutions of higher learning. She offered me enough time to know what I wanted in spite of her busy schedule.

My last respondent was working at a childcare centre on a half day basis. We met at the centre in the evening and had two hours of discussion. She was quite easy going and I enjoyed my time with her.

Results and Findings

Findings

Respondent I

- Background and Arrival in Norway

- She was born and raised in Norway

- She was engaged

- She had no children

- She was born in Norway in 1989

- The Norwegian Language

- She finished secondary school in Norway

- She speaks more Norwegian on a daily basis.

- She did not need a Norwegian course because she schooled in Norway

- Education and job

- She had education qualifications from Norway

- She had never worked in Pakistan

- She in secondary school in Norway

- She may pursue further education after finishing secondary school

- She does not work

- She has never worked

- She has never tried finding a job

- She did not feel like she had many responsibilities at home

- She said that she did not see any value in being at home and would rather work.

- Family Patterns

- She lives in a nuclear family

- She has never lived in Pakistan

- She is satisfied with living in an extended family

- She felt that men and women in her family work equally

- She agrees that most Pakistani families have divided responsibilities

- Culture and tradition

- She feels that some women stay at home without a job due to lack of Norwegian language skills.

- She agrees that the first generation Pakistani women did not have the opportunities which second generation Pakistani women have today.

- She believes that shared responsibilities- where men work outside and women work at home and take care of kids- are the reason many Norwegian-Pakistani women stay at home.

- Expectations for her Own Children

- She agrees that regardless of gender, everyone should study and work.

- She agrees that her daughters should be able to learn to control their own lives, careers and their finances.

Respondent II

- Background and Arrival in Norway

- She was married

- She came to Norway after she was married

- She had a son aged 27, another aged 12 and a daughter aged 20

- She came to Norway in 1974