Introduction

In the United States, all children have the right to receive education in public schools in spite of their social status. The federal laws also protect the rights of immigrant students without references to their status of illegal immigrants or unaccompanied minors (Schmid, 2013). Nowadays, in the U.S. schools, two students among thirty students in a class are immigrants, and the researchers state that these statistical data can be even understated (Adelman & Taylor, 2015; Darden, 2014). The number of immigrant students enrolled in schools increases each year. The U.S. Department of Education in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Human Services regularly provides new guidelines that are oriented to propose the appropriate action plans to public schools (U.S. Department of Education, 2014; U.S. Department of Human Services, 2014).

The main goal is to address the social and educational needs of all students in the United States and create comfortable environments for learning the English language and improving academic performance. Although the number of immigrant students increases, more attention is paid to the realization of federal laws and principles regarding the education of the immigrant population, services proposed in the majority of public schools cannot address the needs of all children (Anderson, 2013). The problem of providing education for immigrant students is important to be discussed in detail like the number of states where public schools address this issue adequately is rather low. Challenges associated with the necessity of placing and enrolling unaccompanied minors and undocumented immigrants are not resolved in the majority of public schools in those states where the number of immigrants is traditionally low.

The purpose of this project is to analyze the situation around the immigration influx and the education of immigrant children, including unaccompanied minors, with the focus on the environmental scanning and propose the change initiative and plan directed toward improving the situation in those K-12 schools where the high number of immigrants is enrolled or expected to be enrolled in the future. Environmental scanning is selected as a tool for collecting the information on the issue, for the detailed exploration of factors that affect the development of the situation in the United States, and for determining the trends that are observed in the area of the K-12 education for immigrants in the country.

Problem Statement

The problem is in the fact that in 2014, the United States faced a new wave of the immigration crisis associated with the significant influx of immigrants, including undocumented and unaccompanied minors, from Central America, Latin America, and African countries (Cuevas & Cheung, 2015). The public schools in many states of the country were challenged to enroll a large number of immigrant children following President Obama’s initiative declared in the summer of 2014 and Executive Actions declared in November of 2014 (Executive actions on immigration, 2015; Martosko, 2014; Mitchell, 2015). According to the initiative, after being located in shelters and migration centers, undocumented immigrant students and unaccompanied minors were re-located in different states of the country where the sponsors or guardians were assigned to them, and where children were enrolled in public schools (Martosko, 2014).

As a result, almost all states of the country faced the challenge of locating a large number of immigrant children. Only in a few states, the educational authorities and public schools were prepared to enroll a large number of immigrants and propose adequate education services according to the McKinney-Vento Act and other legislation. The appropriate initiatives and change plans were proposed and implemented in Maryland, Virginia, and California and some effective steps to address the crisis were made in New York, Texas, and Florida (Bowie, 2015). Currently, the immigration crisis seems to be intense, and many public schools in states with the high number of coming immigrants need to reform their educational programs and curricula in order to respond to the problem.

Environmental Scanning: Overview

Environmental scanning can be discussed as the analysis of external factors, issues, and trends that are associated with the development of the concrete problem or phenomenon. The primary task of the environmental scanning in this project is to represent how the issue of providing the education for immigrants and unaccompanied minors developed from the historical perspective, and what trends can be observed today, as a result of President Obama’s initiatives related to the immigration policy.

First, the scope of the issue should be examined with references to the studies and governmental reports published online. The immigrant population in the United States is more than 40 million people. Among them, about 11 million people are referred to as unauthorized immigrants, and more than 1 million people are undocumented immigrants (U.S. Department of Human Services, 2014). The term ‘unaccompanied minor’ is used for a child who lives on the territories of the United States without a parent who is a legal migrant and without a legal guardian (Martosko, 2014). According to the recent data provided by the U.S. Department of Education, over 800,000 immigrants are of the school-age, and professionals state that this number tends to increase in the future (U.S. Department of Education, 2014).

The statistics demonstrate that the number of unaccompanied minors in 2012 was more than 13,000; and in 2014, there were 60,000 illegal immigrant children in the United States (Figure 1; U.S. Department of Human Services, 2014). The number of school-aged immigrants increased by three times since 1990 (Cuevas & Cheung, 2015). Immigrant children usually come from the countries of Central and Latin America, as well as African countries. The largest number of immigrants comes from Guatemala and El Salvador. There is a tendency for the increasing number of Africans among immigrants. According to Roubeni, De Haene, Keatley, Shah, and Rasmussen (2015), in 2010, “one in five Black immigrant students in New York City public schools Grades 1 through 8 was born in Africa” (p. 279). These data provide information on the scope of the issue.

While searching the chronological data on the topic and discussing the problem from the historical perspective, it is important to note that the issue of providing the educational services for immigrant children became actively discussed in 1982, in association with the Plyler v. Doe case (Stottlemyre, 2015, p. 297). In that case, the U.S. Supreme Court presented the decision regarding the K-12 school education according to which state or school authorities cannot limit students in the right to receive the education in spite of their immigration status (Cuevas & Cheung, 2015). In the United States, illegal immigrant children have the right to receive education in public schools as any other children (Anderson, 2013).

In addition, federal funding is provided for immigrant children despite their legal and language statuses (Adelman & Taylor, 2015). In 1987, the McKinney-Vento Education of Homeless Children and Youth Assistance Act was adopted, and it guarantees the support for homeless children, including immigrants. One of the Act’s provisions is the enrollment of immigrant children in public schools (Wynne et al., 2014). This principle was taken as a fundamental one when statements of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program were formulated (Cuevas & Cheung, 2015; Gonzales, Terriquez, & Ruszczyk, 2014).

The DACA program was adopted in 2012 to provide young illegal immigrants living in the United States longer than five years with certain guaranteed rights, such as the impossibility to be deported. In 2014, the United States faced the immigration crisis, and the question of the immigrant children’s education became of current interest. In May of 2014, the U.S. Department of Justice and the U.S. Department of Education provided state and school districts with the official reminders on the necessity to provide them equal access to education for all students, in spite of their immigration status (U.S. Department of Education, 2014). States also adopted the norm according to which K-12 school authorities have no right to ask students about their immigration status (Adelman & Taylor, 2015). Responding to the crisis, in November of 2014, President Obama declared the expansion of the 2012 DACA program in order to provide more support for the undocumented children.

The expansion of the DACA program was aimed at improving the conditions for immigrant children and addressing the right to education. Following the President’s initiative, “the federal government has sent more than 37,000 illegal immigrant children to adults in every part of the U.S. who claimed to be their guardians” (Martosko, 2014, para. 1). It is possible to state that this initiative will be supported during the next years as according to the Migration Policy Institute data, “39,000 immigrant children will enter the United States as unaccompanied minors” in the following fiscal year (Mitchell, 2015, p. 14). The focus on the policy promoted by President Obama resulted in the fact that in 2014, more than 85% of immigrant children were placed with guardians or relatives (Executive actions on immigration, 2015). The highest number of guardians is observed in such states as New York, Maryland, Virginia, California, Texas, and Florida (Figure 2; U.S. Department of Human Services, 2014). Authorities in these states claim the lack of resources to provide educational services for all immigrants.

The education of immigrants is funded according to the needs of the concrete state with references to the per-pupil expenditures. In the context of the federal education program, in 2011, about $400 million was spent supporting the immigrant education services, but these resources are usually not enough (U.S. Department of Human Services, 2014). In these states, immigrant students are also provided the additional mental and health services while being monitored by the social workers. According to Mitchell (2015), these students, “many with yearlong gaps in their formal education and suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder”, represent “a significant new challenge for schools” (p. 14).

Additional challenges include “the need to ramp up new English language learner classes, reconcile cultural disconnects, or accommodate mobile populations” (Darden, 2014, p. 76). In Maryland, the school authorities expect the increases in the immigration flows and test a new curriculum and a program for English learners. In Prince George’s County, two schools were opened only for immigrants to improve their knowledge of English and culture (Bowie, 2015). These steps aim to address the problem of increased immigration and the issue of providing effective education for all students without references to their immigration status.

Literature Review

President Obama’s initiative that was oriented to the relocation of immigrant children from shelters and migration centers to families or sponsors who can perform the role of guardians led to the necessity of creating the additional conditions for these children to be enrolled in schools. Following Gonzales et al. (2014), this action is important as only those students having guardians among relatives, respected persons, and friends of a family can be enrolled in public schools and be protected under the U.S. laws in the area of education for immigrants. Schmid (2013) states that this situation is rather dramatic for several parties: children who are known as unaccompanied minors, sponsors, and school authorities who face the problem of enrolling a large and often unexpected number of students.

Adelman and Taylor (2015) pay attention to the fact that the challenges faced by state officials and authorities in schools are numerous, and one of the main issues is “addressing students with the limited English language and cultural differences, both of which may generate behaviors among peers and staff that are associated with prejudice and discrimination” (p. 325). On the other hand, “immigrant students should feel accepted from the start and able to embrace the unshakeable sense of belonging” (Darden, 2014, p. 77). Officials in K-12 schools need to respond to both educational and psychological aspects of the immigrants’ enrollment.

The situation of supporting unaccompanied minors aimed at decreasing the risk of deporting children has rather negative results for school districts and communities in many states of the country (Jefferies, 2014). Departments of education in states where the flow of immigrants is the largest one try to address the problem while proposing effective educational curricula to meet the needs of students who do not speak English, have limited language skills, and who are enrolled in schools according to the guardian program (Plascencia, 2014). According to the McKinney-Vento Act, an immigrant child without a stable address cannot be denied to attend the public school, and this situation provides a feeling of stability in children.

The opposite side of this situation also exists. According to Cuevas and Cheung (2015), the conditions in which immigrants and unaccompanied minors find themselves while coming to the United States “have created a sizable vulnerable population that requires attention, including research and practice-based solutions in schools and communities” (p. 310). The educational programs developed in such states like Maryland, Virginia, and New York among others should address the immigrant children’s needs for the development of language skills, emotional, and health support (Bowie, 2015; Mitchell, 2015). Portes (2015) notes that the problem is in the fact that the appointment of a sponsor or a guardian cannot mean that a child will be quickly enrolled in a school.

In spite of the fact that in the United States, “there is consensus that schools should welcome and orient newcomers, enhance English language skills of those with limited English proficiency, and connect families with neighborhood services as much as feasible”, the number of immigrant students that require the assistance is large (Adelman & Taylor, 2015, p. 329). Portes (2015) claims that the main causes of the limited services provided to unaccompanied minors are the undeveloped educational programs and the lack of financial resources although the United States guarantees the additional funding for supporting immigrants.

The development of effective strategies for providing the educational support and services to immigrant children is the necessary step that should be taken at the state level. Researchers propose to refer to the experience of such states like California, Maryland, Virginia, and New York in addressing the needs of unaccompanied minors (Adelman & Taylor, 2015; Bowie, 2015). It is possible to select the strategy that can be adopted in the concrete school in order to respond to the consequences of the immigrant crisis. According to Ntuli, Nyarambi, and Traore (2014), such efforts are necessary in order to guarantee the effective integration of the immigrant population in the United States.

The focus on the development of educational programs for public schools is the first step to support not only unaccompanied minors but also immigrant children from families where the parents are illegal or undocumented immigrants (Plascencia, 2014). Schmid (2013) states that the educational authorities’ attempts should be directed toward planning and developing interventions that are most effective to enroll the immigrant students, retain them in schools, and provide the emotional and psychological support. Greenfield and Quiroz (2013) agree with the other researchers that the focus should be on providing students with such educational opportunities that can be beneficial for them to avoid the academic failure, stress, and bullying in schools.

The problem is in the fact that many schools cannot provide immigrant students with the adequate support in terms of the development of English and native language skills and improvement of their overall performance. Portes (2015) and Cuevas and Cheung (2015) point to the fact that although schools demonstrate their attempts to address the needs and interests of the immigrant population, the results are often negative as schools cannot cope with the large flows of non-English speakers and the prejudice in classes. Cuevas and Cheung (2015) state that “schools can be sites of both inclusion and marginalization, that teachers can be perceived as both advocates and adversaries” (p. 312). Under such conditions, the effective educational initiatives are the necessity. School can choose whether to support the participation of immigrant children in language programs for newcomers or develop the courses within the educational program for the concrete school setting.

In spite of the researchers’ focus on the weaknesses in realizing President Obama’s initiative at the level of public schools, Cuevas and Cheung (2015) pay attention to positive results of the federal programs oriented to supporting immigrant children in the country, as the Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents (DAPA) had the same positive effect on the immigrant population as the DACA, and both “the DAPA and the expanded DACA programs are estimated to affect 4.4 million individuals” (p. 311). These results can be viewed as positive. A large number of unaccompanied minors can receive the required social support, psychological assistance, language assistance, and educational support without risks of being deported (Motti-Stefanidi, Masten, & Asendorpf, 2014).

The researchers note that the process of adapting the educational programs and curricula in public schools of different states will be rather long and challenging as the number of immigrants increases each year while changing the overall demographics at schools (Schmid, 2013; Seif, Ullman, & Nunez-Mchiri, 2014). Jefferies (2014) argues that more attention should be paid to the interaction between the immigrant families, guardians, schools, and communities in order to achieve more positive results in the process as the involvement of all parties is important. In their turn, Adelman and Taylor (2015) state that the situation in 2014 added to the understanding of the problem and the urgency of proposing effective means to address it, and this fact can lead to positive consequences for immigrant children, schools, and communities. The effective treatment of immigrant children in schools is based on the appropriate actions of educational authorities while developing programs and curricula to address the issue of the immigration influx.

Problem Analysis

The results of environmental scanning and literature review on the problem of the immigrant education demonstrate that the issue is based on several important factors that need to be identified for the further analysis. In order to discuss the influence of the factors on the development of educational systems in states, it is necessary to refer to the leadership theory. The focus should be on the transformational leadership as the key to adjusting to social trends, changes in school demographics, associated threats, and opportunities. The first factor that needs to be discussed is the capacity of public schools to cope with the constantly increasing number of immigrant children, including unaccompanied minors (Cuevas & Cheung, 2015).

The second factor is the necessity for school authorities to provide not only educational services but also the psychological, emotional, mental, and social support in the context of schools (Mitchell, 2015; Ntuli et al., 2014). One more important factor is the necessity to address the language problems of immigrant children (Cuevas & Cheung, 2015; Darden, 2014). These factors or issues are key ones in influencing the K-12 schools’ approaches to addressing the problem of the increased immigration and the necessity to enroll a large number of unaccompanied minors and undocumented children.

The analysis also includes the discussion of the current status of the determined issues with the impact on the K-12 educational system. The number of immigrant children has increased by more than three times during the recent years, and the data demonstrate that the growth in the school-aged immigrant population is not equable in all states of the country (Cuevas & Cheung, 2015; U.S. Department of Human Services, 2014). The largest numbers of unaccompanied minors are enrolled in schools in such states like New York, Maryland, Virginia, California, Texas, and Florida (U.S. Department of Education, 2014; U.S. Department of Human Services, 2014). The reason is in the fact that these states have the largest numbers of guardians or sponsors for illegal immigrants and unaccompanied minors.

The current situation regarding the provision of the additional support for immigrant children is even more problematic as school authorities should guarantee the psychological, health, and mental support for newcomers, immigrants living in new families, having undocumented parents or receiving the assistance of guardians. At the current stage, only the limited number of public schools has the adequate funding to provide the assistance for immigrants suffering from stress and adaptation problems (Wynne et al., 2014). The other problem is the provision of opportunities to attend the additional English language courses or classes. The majority of immigrant children from Guatemala, El Salvador, Mexico, and other Latin American and African countries have the limited proficiency in English, and school teachers need to have the knowledge of these students’ native languages, as well as to guarantee the students’ inclusion in the learning process in the class (Portes, 2015; Seif et al., 2014). Currently, teachers in many classes face a challenge of addressing the language needs of immigrant students.

The impact of the identified factors on the development of the K-12 school system is critical. K-12 schools in New York, Maryland, Virginia, California, Texas, and Florida faced the most urgent problem of addressing the increasing number of immigrant children in schools, and the educational authorities were most proactive to respond to the problem in the 2014-2015 academic year while proposing the change in the educational program and curricula. There were organized special classes for immigrant children to unite immigrants with the same level of the language proficiency in the appropriate settings. In addition to the improvement of the educational services provision, the health, psychological, and social support was proposed to immigrant children who need to overcome the stress of living in another country, post-traumatic syndrome, and stress associated with the adaptation in schools (Darden, 2014; Greenfield & Quiroz, 2013). In this context, the school authorities need to perform as transformational leaders who are open to adapting the school system to the new demands, as well as motivating the staff to accept these changes.

It is also possible to predict the future progress of the problem with references to its current status and trends. The authorities and researchers expect the larger amounts of immigrants during the next years (Adelman & Taylor, 2015; Mitchell, 2015; U.S. Department of Education, 2014). This problem can be addressed with the focus on improving the curricula in schools following the examples of Maryland and Virginia, where new schools for immigrants are opened and where new language courses are implemented (Bowie, 2015). These steps are important to address the future progress in the problem. Researchers predict the constant increase in the immigrant population and the problem is in the fact that “there is relatively little leadership and infrastructure for integrating efforts to enable equity of opportunity for success at school” (Adelman & Taylor, 2015, p. 329).

More schools need to be changed in order to address the necessity of enrolling more immigrant students whose knowledge of the English language can be even lower than now, and more unaccompanied minors will need the support of social workers and educators in addition to the guardians’ assistance. Educational leaders need to prepare their staffs to the predicted changes in the number of students, and they should motivate and persuade the stakeholders to develop and adopt reforms in the activities of the K-12 schools.

These issues also have the effect on the planning in public schools and implementation of changes in the system in order to adapt to the challenges. The necessity to cope with the influx of immigrant children that have the limited English language competence leads to creating new classes and groups for English learners among immigrants (Adelman & Taylor, 2015). Developing the change initiative, the school leaders need to plan the actions that are most effective in order to cope with a large number of immigrants who require the additional language training and psychological, mental, and social support. At this stage, following the experiences of K-12 schools in Maryland, Virginia, and California, transformational leaders in other states can plan their own activities in order to address the issues with the help of opening more classes and groups for immigrants, guaranteeing the enrollment of all immigrant children in spite of their status, and providing the required psychological, health, and social support.

Change Initiative

K-12 schools in states where the immigration influx is large or expected to increase in the future require the effective change initiative or educational plan to be implemented in order to address the challenge. The analysis of the data according to the environmental scanning demonstrates that the most appropriate planning model should refer to the significant role of changes in the society as a factor to influence the K-12 school system in the concrete state of the country. Roger Kaufman’s Organizational Elements Planning (OEM) model that is based on the Mega Planning theory is most advantageous to be utilized in the situation when it is necessary to address the societal changes at the organizational level (Altschuld & Watkins, 2014).

The selected OEM model is grounded on such components and principles as the focus on the needs assessment, the focus on processes and means as resources to conduct the change process, the focus on the Mega or societal level, the focus on the Macro or organizational level, and the focus on the Micro or group level within an organization (Altschuld & Watkins, 2014). This OEM model allows the effective planning under the impact of social processes, and the result of this planning is the response and adaptation to changes at the Macro level with the associated transformations at the Micro level.

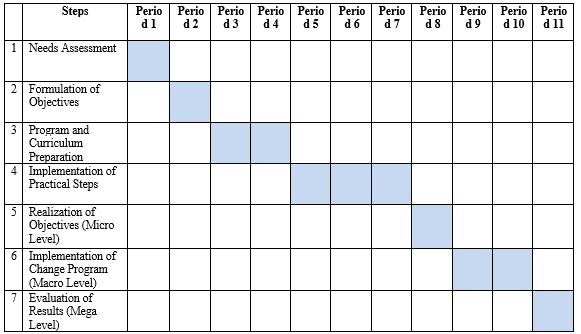

The plan formulated according to the OEM model for K-12 schools in states with the high rates undocumented immigrant children and unaccompanied minors should include seven steps (Table 1). The first step is the needs assessment that is performed with the focus on expected needs of the immigrant population in a state and with the focus on the material resources required by public schools to accept the proposed change. The second step is the formulation of objectives for the K-12 school authorities that are associated with the necessity of opening more separate classes for immigrant children and providing the psychological, health, and social support to children. The third step is the preparation of the educational program and curriculum oriented to immigrant children with different levels of the language proficiency and the recruitment of bilingual teachers.

The fourth action is the use of resources and implementation of the following practical steps:

- the opening of classes for immigrant children, including undocumented immigrants and unaccompanied minors;

- the assignment of bilingual teachers for the work with immigrant students;

- the integration of the educational program for English learners that is developed to improve their language skills and academic performance;

- the provision of the obligatory counseling, health assessment, and social support for immigrant students in new classes despite their status.

- The fifth step is the realization of objectives and practical strategies at the Micro level when educators are motivated to work with the immigrant population and receive the required training and consultation.

- The sixth step is the implementation of the change program at the Macro level when the work of a school is modified according to the needs for opening new classes and the actual adoption of the change initiative.

- The seventh step is the evaluation of results at the Mega level with the focus on the possibilities of the program to address the immigration issue in the society.

It is possible to identify both strengths and weaknesses in the proposed planning process and change program. The strengths are in the fact that implementing the proposed program, K-12 schools become able to create the comfortable conditions and environments for immigrant children suffering from stress and traumas, as well as having the limited proficiency in English (Adelman & Taylor, 2015). The enrollment of immigrant children becomes effectively organized. Weaknesses include the impossibility to predict the actual number of immigrant students to be enrolled in each public school in the state, and the number of immigrants can change every day (Darden, 2014).

As a result, new classes for immigrant children can be opened any time during the year, depending on the immigrant enrollment rate, and the teachers can be required to work part-time, interacting with small groups of immigrants or specializing in additional courses when the immigrant rate is low. Such dependence on the societal changes creates the additional barriers to the effective implementation of the change plan. The plan should include strategies that address the identified issues.

The proposed plan should be implemented in the public schools of Ohio where the number of unaccompanied minors remains to be comparably high: more than 600 in 2014, and more than 450 in 2015 (U.S. Department of Human Services, 2014). The implementation of the plan can be associated with a range of expected and unexpected changes in the work of K-12 schools in Ohio. The expected positive changes are the creation of adequate environments for immigrant children; the improvements in the academic performance; the improvements in the knowledge of the English language; the protection of the immigrant children’s rights; and the provision of the effective support for immigrant children living under different circumstances in the community (Cuevas & Cheung, 2015; Martosko, 2014). If the realization of the change plan at the Mega level is expected to have positive consequences, the realization of the proposed plan at the Macro and Micro levels can be a challenging task.

The problem is based on the necessity to assess the needs of each community for opening separate classes in public schools for immigrants adequately and with references to the U.S. Department of Education and U.S. Department of Human Services’ statistics. Public schools in Belmont County and Clermont County in Ohio have the high rates of newcomers, and they should have the potential for opening classes for immigrant children in order to address their educational needs in accordance with the federal laws regarding the education of the immigrant population (Portes, 2015). The problem can be observed when predictions made regarding the number of immigrant students are not realized, and the rate of immigrants is significantly higher or lower than the foreseen levels.

The appropriate response to the possible negative consequences of adopting the proposed plan should be based on the idea of flexibility. Although the opening of additional classes for immigrant children in Ohio public schools depends on the constantly changing rate of school-aged immigrants coming to the state, it is necessary to implement the plan gradually and with the focus on the actual situation. The curriculum in new classes should be focused on developing the children’s language skills. As a result, the curriculum can be discussed as both preparing immigrant children to be integrated into mixed classes and independent to guarantee the provision of education for immigrant children during a long period of time (Adelman & Taylor, 2015; Jefferies, 2014).

If the immigrant enrollment rate is high before the start of the academic year, K-12 school authorities in Belmont County and Clermont County should initiate the opening of classes. If the rate is low, the authorities should address the problem at the Micro level and organize the additional language courses for groups of immigrants in mixed classes. In a situation when the number of enrolled immigrant students changes during the year, it is possible to open separate classes as all the required resources are planned and available. The main conditions to follow in this case are the provision of the language education, assignment of bilingual teachers for courses and instructions in separate classes, and provision of the counseling and health assistance for immigrant children.

Conclusion

President Obama’s initiative to guarantee the protection of immigrant children’s rights and provide the education to all of them was a trigger for officials in states to develop new educational programs and strategies in order to address the high immigrant enrollment rates. The conducted environmental scanning indicates that the immigration influx observed in 2014 can be also expected in the future, and K-12 school authorities should be prepared to the challenge. While referring to the initiatives adopted in such states as Maryland, Virginia, California, and Florida, it is possible to formulate the change plan for the other states where the immigration rates are high.

The focus is on addressing the needs of undocumented school-aged immigrants, as well as unaccompanied minors. The re-location of immigrant children to different families over the country and the provision of the guardian support is the actively developing practice in the United States. Schools in different regions of the country need to have the plan on how to respond to unexpected changes in the number of enrolled immigrants. The plan proposed in this project is appropriate for public schools in states where the number of guardians is high, and which are attractive to immigrant families and unaccompanied minors.

The implementation of the proposed plan for the change should be realized as a flexible process that is based on the effective needs assessment, the use of resources, and the integration of the concrete, practical steps. The plan for the change can be more effective when public school authorities allow the flexible implementation of its elements. If the integration of the counseling and health support for immigrant students and the provision of the language training are the obligatory components of the change initiative that are implemented under circumstances in public schools, is important to state that the opening of new classes or courses depends on the actual number of enrolled immigrants. This approach is effective to respond to the social trends and address the necessity to provide immigrant students with the effective educational services and support at the Mega level. As a result, the change plan can be successfully adjusted to the situation in the concrete community, allowing officials to meet the public needs.

References

Adelman, H., & Taylor, L. (2015). Immigrant children and youth in the USA: Facilitating equity of opportunity at school. Education Sciences, 5(1), 323-344.

Altschuld, J. W., & Watkins, R. (2014). A primer on needs assessment: More than 40 years of research and practice. New Directions for Evaluation, 144(1), 5-18.

Anderson, N. B. (2013). The promise of Plyler: Public institutional in-state tuition policies for undocumented students and compliance with federal law. Washington and Lee Law Review, 70(4), 2339-2388.

Bowie, L. (2015). Maryland lawmakers call for better education, more support for new immigrants. The Baltimore Sun. Web.

Cuevas, S., & Cheung, A. (2015). Dissolving boundaries: Understanding undocumented students’ educational experiences. Harvard Educational Review, 85(3), 310-317.

Darden, E. C. (2014). School is open for immigrants: Children of undocumented immigrants have a right to a free, public education, but schools and the children themselves still face challenges. Phi Delta Kappan, 96(1), 76-77.

Executive actions on immigration. (2015). Web.

Gonzales, R. G., Terriquez, V., & Ruszczyk, S. P. (2014). Becoming DACAmented: Assessing the short-term benefits of deferred action for childhood arrivals (DACA). American Behavioral Scientist, 58(14), 1852-1872.

Greenfield, P. M., & Quiroz, B. (2013). Context and culture in the socialization and development of personal achievement values: Comparing Latino immigrant families, European American families, and elementary school teachers. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 34(2), 108-118.

Jefferies, J. (2014). The production of “illegal” subjects in Massachusetts and high school enrollment for undocumented youth. Latino Studies, 12(1), 65-87.

Martosko, D. (2014). Revealed: Where 37,000 illegal immigrant children have been released to ‘guardians’ across America – and where the feds are hiding tens of thousands more. The Daily Mail. Web.

Mitchell, C. (2015). Undocumented students strive to adapt. Education Week, 34(29), 14-15.

Motti-Stefanidi, F., Masten, A., & Asendorpf, J. B. (2014). School engagement trajectories of immigrant youth risks and longitudinal interplay with academic success. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 39(1), 32-42.

Ntuli, E., Nyarambi, A., & Traore, M. (2014). Assessment in early childhood education: Threats and challenges to effective assessment of immigrant children. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 14(4), 221-228.

Plascencia, L. (2014). Book review: No Undocumented Child Left Behind: Plyler v. Doe and the Education of Undocumented Schoolchildren by Michael A. Olivas. Latino Studies, 12(2), 318-320.

Portes, A. (2015). Assimilation without a blueprint: Children of immigrants in new places of settlement. Past as Prologue, 1(1), 221-226.

Roubeni, S., De Haene, L., Keatley, E., Shah, N., & Rasmussen, A. (2015). “If we can’t do it, our children will do it one day”: A qualitative study of West African immigrant parents’ losses and educational aspirations for their children. American Educational Research Journal, 52(2), 275-305.

Schmid, C. (2013). Undocumented childhood immigrants, the Dream Act and Deferred Action for childhood arrivals in the USA. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 33(12), 693-707.

Seif, H., Ullman, C., & Nunez-Mchiri, G. G. (2014). Mexican (im)migrant students and education: Constructions of and resistance to “illegality”. Latino Studies, 12(2), 172-193.

Stottlemyre, S. (2015). Strict scrutiny for undocumented childhood arrivals. Journal of Gender, Race and Justice, 18(1), 289-311.

U.S. Department of Education. (2014). Guidance letter to school districts. Web.

U.S. Department of Human Services. (2014). Fact sheets. Web.

Wynne, M. E., Flores, S., Desai, P. S., Persaud, S., Reker, K., Pitt, R. M.,… & Ausikaitis, A. E. (2014). Educational opportunity: Parent and youth perceptions of major provisions of the McKinney-Vento Act. Journal of Social Distress and the Homeless, 23(1), 1-18.