One of the most exciting challenges affecting family businesses is the succession of management, which results in the limited survival of transition businesses. While considering this effect, Chinese companies have been increasingly making their launch to dominate the private sector. The rise suggests that the social capital transfer strategy, value, structure, or communication have different effects on company performance. In this light, the high growth rate of family businesses in China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan has drawn the attention of many scholars. Study on the values that impact the succession choice before transfer event for leadership, control, and ownership control has constituted a large portion of business research. The growing complexity of the business environment creates frequent dilemmas when transferring family businesses to either one successor or share across all children. The paper explores the comparison between China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong family social capital transfer based on the performance of the businesses after succession.

Background Information

Family businesses are owner-managed enterprises with the family members playing significant managerial and financial control. Their setting represents all vital components of private businesses that thrive in less stable economic conditions. Therefore, it is worth understanding the effects of changing the ownership or management setting of the family businesses. Efficient operation and succession of family businesses are believed to play an essential role in the national economy. China has emerged as a stable economy supported by the quick rise of family businesses. To some extent, this suggests that family social capital is tied into the founder generation to ensure the durability of the business networks related to the given family firm.

In China, the viability of family business succession centers a lot of concentration on the incumbent’s and successor’s points of view. This guarantees that relationships and connectivity enhance the performances at the workplaces to the high-tech world. Indeed, family business succession builds and retains the existing networks that are valuable to the business. Based on a family system theory, the Chinese formalize family business succession to respond to all stakeholders’ interests and viability.

The satisfaction of business succession strategy remains relevant to many stakeholders uniquely. In this regard, Chinese societies have various degrees of control and management that show predominance in certain areas. Indeed, the Chinese management structures control a large portion of the Asian economic growth with identifiable ethical enclaves. The collective performance suggests that family business succession in China preserves an open door for suggestions. After all, Chinese family enterprises have an extraordinary business model that ensures success in the start, management, and succession.

A succession of family businesses has been regarded as a critical problem in other settings. However, the high rate at which Chinese family businesses grow invokes the curiosity to understand the strategies, structure, value, and communication used in family social capital succession. The internal authority and control of the centralized businesses ensure that family businesses maintain characteristic decision-making and reduce the opportunities for non-family members to acquire management positions. Therefore, it solves the trust issues, but there is little explanation for addressing the frequent dilemmas as incumbents and successors transfer their leadership roles.

Literature Review

Research on family business succession in China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan has been incited by transfers being done at the last minute. Today, family businesses represent 80% of the global business structures, yet they have a meager rate of successful transgenerational succession (Gagne et al., 2019). However, on this short notice, the Chinese managed to develop extensive business networks guarded by the moral contract to deal with the external environments.

Effective succession is a skill that shows how Chinese families prepare for the challenges and risks associated with family social capital succession from an elder to a younger generation. The configuration of network ties between the elder and younger generations is highly accurate to ensure the effective transfer of leadership and physical assets. Chinese have stayed ahead of the drastic implications that are likely to devalue employees’ commitment because their business successors are confident in the perception of incumbent support (Gagne et al., 2019). The economic integration of the teams has always been associated with a regional grouping, which explains how families deal with arising challenges or prepare for them in advance.

In scholars’ view, Chinese family businesses are regarded as expandable enterprises whose quality of human resources management is highly doubted. The combination of management techniques and tricks has defined the ownership of these kinds of businesses. Family businesses have distinct forms that make them worth studying due to their impacts on both economy and outperformance of the non-family businesses. Dedicated analysis shows that family businesses in China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong have a higher return on investment and do not need outside capital support. Transcending a family business from one generation to another relies on the family members’ satisfaction and the effectiveness of the process.

Incumbent support to the Chinese successors has been associated with intrinsic motivation and trust between the founder and successor generation. In this view, Chinese businesses have had a strange way of maintaining the family integrity and satisfaction of the stakeholder’s interests. Chinese understand the duo importance of the incumbent and successor psychological states to determine succession outcomes (Gagne et al., 2019). Therefore, observations on these processes help break down the selection of successors to assume given positions.

Family business succession in china involves more than a single-step transaction between generations. Perhaps, this strategy has helped China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan refine the inheritance process. In the Chinese culture, succession dilemmas seem to occur less often because successors are grown in the businesses they are likely to inherit. Under this consideration, the continuation of earlier founded businesses is far-reaching and considers all the effects observed on the physical assets.

According to the existing literature, family capital succession mainly focuses on transferring human capital. Three relevant factors determine the effectiveness of succession. The entire process demands succession planning, desirable successor traits, and training. The characteristic sizes of family businesses and the experienced financial constraints are everyday challenges that could not increase employee attention during succession (Mustafa et al., 2019). Different families opt to transfer their businesses to experienced juniors based on the regional success of family businesses in China. The approaches used by Chinese family businesses show that founders and owners understand the role of gender influence and differences in the learning modes of potential successors (Mustafa et al., 2019). Chinese firms have mastered addressing the critical factors that determine the effectiveness of family social capital succession.

Scholars have identified the factors that contribute to successful family business inheritance in different contexts. For instance, the attention devoted to human capital has always been overlooked during the transfer of ownership and leadership of family businesses. Chinese business contexts focus on human resources development and believe this is a business factor that cannot be scaled down during succession (Mustafa & Elliott, 2019). As compared to consumer ties, the entrepreneurial interests of the successor are less influential in the choices of who should be vetted for a given position in the family business. In this regard, it is worth considering the vicious circle restrictions that affect the effectiveness of succession should be broken.

In China, successful companies like LLK Co, which manufactures flavors, have been built on expandable family businesses. The organization has survived and thrived profitably across four generations. The secret behind this success and maintenance of total family control over the company is that Chinese family businesses have distinctive features to accommodate managerial innovation (Mustafa & Elliott, 2019). Case studies to compare the longevity of family businesses in China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan have been conducted to determine how they survive from one generation to another.

Family Social Capital Definition

Family social capital is an exciting research topic that attracts experts to study family behavior. Social capital in family businesses lacks a theoretical justification because the owner’s interests overlap the managers’ benefits. The factors that influence the succession choices in the Chinese-Australian family businesses include vision, managerial style, and family harmony. In most cases, the successful inheritance of business targets solving all financial problems, discrimination, and rising competition. In this case, family business succession is complex and involves many processes, including cross-cultural adaptations. The Chinese cultural heritage has been associated with social and economic business resources in family-based enterprises, making it a transnational phenomenon.

In China, it is hard to determine the success rate of family-based enterprises based on the social history. Most family businesses transition from the founder generation to the second one under different challenges. The potential of the social capital resources constituting these businesses is thrown into social intercourse daily. To some extent, the nature of social capital can be tangible because its value is recognized during the ownership and management transfer. The speculative transition is shaped by distinctive cultures and can explain the regional differences in family business performances.

It is believed that the social connection associated with family business relationships reciprocates the benefits to the planners’ interests. The creation of intellectual capital uses structural, relational, and cognitive strategies, which have different influences on inter-firm activities. The interrelationships give rise to the agency theory, which explains the reliability and credibility of family businesses. The literature gaps in the definition of family social capital have made it hard to learn the lesson like temporal underpinning, legal set-up, institutionalization, and organization of family businesses.

The Characteristics of Chinese Family Businesses in the Mainland

Since 1978, when China’s monetary reforms began, private-operated enterprises (POEs) have been produced instead of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) for more than 37 years. POEs have played a significant role in China’s social and monetary transformation during this time. POEs accounted for 68.3 percent of business compounds in China by 2012. In the contemporary and administrative areas, POEs controlled 70% of the resources. As a result, family business research and succession in china has been among the most discussed topics, especially women’s integration in the succession process (Kubiek & Machek, 2019). The majority of these POEs were organized around the family, with family members claiming, directing, or managing the enterprise.

A significant number of the examination issues confronting researchers of Chinese family businesses are like those looked by specialists on privately-run companies in different regions of the planet: objectives, administration, progression, professionalization, privately-run company struggle, acute administration, human asset the board, advancement, and determinants of execution. A few issues might be unique to China. However, different issues for all family firms present unmistakable difficulties for those working inside China’s specific political, social, and financial construction. Therefore, the fragmented roles of different stakeholders have introduced multiple directions of future study on family business succession (Kubiek & Machek, 2019). Until now, a generally little review has occurred on how the changing cultural qualities in blend with the advancing foundations in the beyond 37 years of monetary progression have affected past advancement and will impact future changes of the family-focused type of firm association in China.

For example, China’s one-child policy and its new unwinding will affect family businesses. Studying the goals that family authors pursued through interfamily progression and their decisions despite limited replacement options can provide valuable insight into the mental, sociological, and financial foundations of those goals and their implications for family firm conduct and execution. Categorizing the environment, context, people, and processes relevant to family business succession simplify co-development-related factors in Chinese family businesses (Kubiek & Machek, 2019). Another model is the co-development of China’s foundations and family businesses, unique globally. Changes in market-based foundations influence family firm conduct and execution. In contrast, family firm owners influence China’s social, monetary, and political organizations through their recently elevated political status and investment in the political cycle.

Chinese Family Firms’ Evolution since 1949

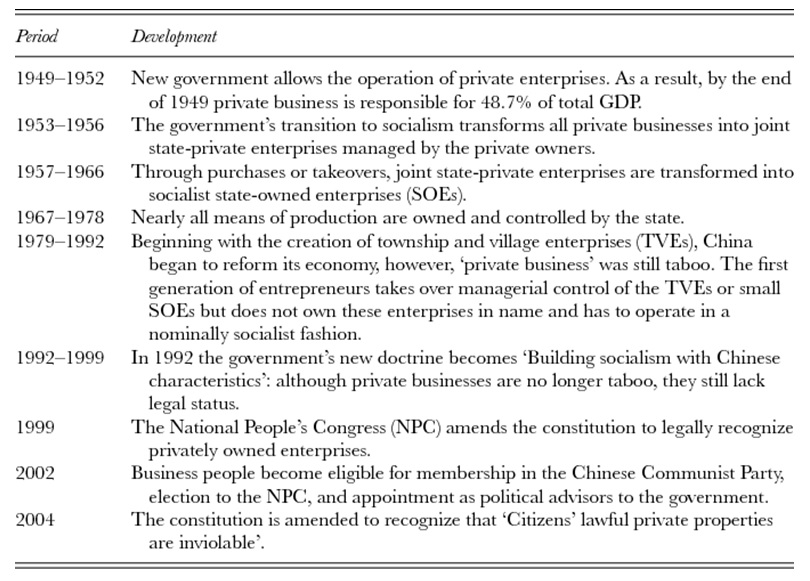

The status and job of POEs in China starting around 1949 have gone through enthusiastic changes given the headway of the country’s stand-out communist politico-monetary perspective, as summarized in Table 1. As Table 1 shows, POEs were suffered in the underlying three years after the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) came to control. In any case, throughout the accompanying 29 years, until 1978, these associations were utterly changed by the public authority into SOEs through purchase, pulverizing out, or seizure.

Before completing this period, all techniques for creation had a spot with the state, and the industrialist class had fundamentally disappeared. In 1978, China started its economic change by allowing remote control of region and town attempts (TVEs), but the business visionaries expected to wear ‘red covers.’ Not until March 1999, when the gathering, the National People’s Congress (NPC), reexamined the constitution to see POEs formally as critical financial components and gave them actual status, did it become futile to cover themselves as TVEs? POEs worked for quite a while, preceding being indeed seen.

According to the National Bureau of Statistics’ Third National Economic Census, POEs as a percentage of the total number of projects increased from 56.8% in examination and innovation administrations to 73 percent in manufacturing. POEs had less work, with 26.7 percent in transportation, warehousing, and postal administrations and 53.0 percent in retail and discount stores families owned 85.4 percent of POEs starting in 2011. A few creators have credited the power of this type of business to the dependable and profoundly inserted impact of Confucianism, which sees the family as essential to getting sorted out a unit of society (Mustafa et al., 2019). Likewise, the administrative advantage is a more prominent issue because of China’s short idea of social, financial, political, and lawful organizations. Thus, the social capital created among relatives, joined with the exceptional capacity of the family to blame its individuals, made people trust relatives more than non-family individuals.

Strategies employed by Chinese Enterprises

China’s monetary advancement has been rapid, yet the excessively massive impact of the privately-run company has been noteworthy. Essentially, it occurred in a climate that inclined toward SOEs and global organizations and saw privately-run companies as less genuine and oppressed them as far as admittance to assets and openings (Mustafa et al., 2019). Notwithstanding the difficulties, family firms now overwhelm the SME area. They have progressively accessed capital business sectors, becoming vast public organizations while effectively clutching family-prevailing proprietorship and control.

Standard speculations researchers propose regarding family firms’ one-of-a-kind asset philanthropically show family businesses as socio-passionate riches that impact their market-situated upper hands. Additionally, hindrances in nondiscriminatory market rivalry can, to some degree, clarify this development since family firm development during China’s change period was just part of the way accomplished by market-arranged contest methodology (EY Greater China, 2020). The non-market-arranged social and political organization methodology to create and take advantage of social connections (counting those with relatives, family members, companions, previous schoolmates, previous partners, and war amigos) and political associations might have been as essential in the deft development of Chinese privately-owned companies.

The Nonmarket Social Network Strategy

The market-arranged development system depends on upper hands gained through advancements, consolidations, coalitions, internationalization, etc. Be that as it may, as China changed, development openings emerged from institutional changes, the formation of new business sectors due to government strategies, and the unwinding of government control (EY Greater China, 2020). To help venture improvement in the businesses that arose out of these chances straightforwardly and in a roundabout way, the Chinese government then, at that point, initiated economic and other monetary strategy changes, like promising assessment approaches and product sponsorships. New financial specialists who wished to make the most of these changes required assets constrained by the public authority and organizations, like SOEs and banks.

For example, the central and local governments could aid by granting access to the property, establishing long-term contracts to acquire labor and products from new specialists, or obtaining financial capital from banks and SOEs. These discussions between monetary experts and government officials were secret and, in general, based on political ties and social connections rather than the open display of ruthless deals. They were nonmarket dealings in this way (EY Greater China, 2020). It is not necessarily the case that market procedures did not assume a significant part; for sure, they shaped the fundamental design that the nonmarket technique required for supportability. This is because admittance to assets and openings did not ensure accomplishment in the commercial center. In addition, a venture with upper hands moving from interesting innovation and information or scale could accomplish considerably higher economic wellbeing and political personality since size had a direct and positive relationship with political standing, societal position, and market position.

In addition, extensions do business and raise extra expenses necessary for the nearby state-run administrations’ exhibition measure. As a result, government officials favored POEs that could achieve market success thanks to the favorable treatment through their nonmarket social and political organization system (EY Greater China, 2020). The achievement of a family association’s market methodologies reared accomplishment in the nonmarket procedures and the other way around in a rhythmic cycle.

Family Governance as Strategic Resource

As previously said, despite the difficulties, family businesses could develop lopsidedly during this period. This strongly suggests that family management provided particular advantages in pursuing the necessary opposition systems. We willlook at three of the most important: Family-owned businesses have reduced operating costs, can adapt quickly to market developments, and can enlist the help of relatives to carry out this nonmarket practice (Mustafa et al., 2019). When a privately held company is in its early stages of development, it commonly can’t bear to employability in the outside work market; in this way, relatives structure a minimal expense ability pool.

Second, the advantage is a significant wellspring of significant worth dissemination. This could be through the compatibility of personal administrative responsibility to the detriment of the proprietors or the spillage of proprietary innovations. Third, the nonmarket interpersonal organization technique requests data mystery about the political associations and extraordinary advantages since data spillage can rapidly make the business lose its upper hand (Mustafa et al., 2019). Relatives, family members, or companions are assigned to fundamental circumstances with essential importance or data control esteem, such as finance administrator, project supervisor, client care director, or human asset chief, by family businesses (EY Greater China, 2020). Due to this, the family will be able to manage asset identification, the progression of essential market data, and the expense structure.

The Chinese use a nonmarket strategy since the most talented people do not always fill the positions on the job market. It gives up the best external chief’s gradual adequacy (apparently more skilled than a relative because the person in question comes from a larger pool of ability) in exchange for strength, the prevention of inside debasement, and the protection of the company’s proprietary innovations through a family arrangement (Mustafa et al., 2019). Any other way, the organizations would need to find intricate and exorbitant frameworks to control possibly broken practices. As a result, family businesses can operate at a cheaper cost.

Small and medium-sized family businesses are typically all-inclusive. Outright control in large corporations, especially public companies, could come via claiming more than half of the offers or through a pyramidal proprietorship structure. Control is also exercised through relatives’ positions on the senior management team and the board of trustees (EY Greater China, 2020). Indeed, even among public corporations, the joined offer possessions of relatives, family members, and companions, joined with the family’s choice and arrangement of agreeable chiefs and administrators effectively moves the overall influence in the family’s approval.

Such outright control permits the family originator to understand their pioneering potential without unnecessary obstruction completely, and it keeps accomplices and outside invested individuals from striking the business. Moreover, parental authority, particularly in the originator age average, stays generally normal during this period. The blend of unchallenged power and kindheartedness permitted the family chief to embrace an incentive initiative style, which worked with asset assembly, fast development, and the dexterous reactions requested by the market (EY Greater China, 2020). Family firms came up short on the innate political associations of the SOEs, so they needed to seek after them purposely and effectively.

The organization of family firms, if practical, could apply an impact on society because of commitments to the development of the total national output (GDP), commitments to government incomes through charges, and the making of the business. The organizations’ beneficent gifts, inclusion in open government assistance projects, and the top supervisors’ very own exercises in the public arena all add to it (EY Greater China, 2020). These could then give political status to the family chief, for instance, as a standard or public warning advisory group part, a delegate to the NPC, an individual from the National Industrial and Commercial Association, or an overseer of the business office.

According to all accounts, these organizations were formed to incite public officials to act in the people’s best interests. However, the corporate visionary may have easily constructed a staggering political structure that benefited the family firm in gaining access to assets and comprehending government arrangements through relationships with government officials (EY Greater China, 2020). The political status would also provide the business visionary and the company with significantly greater credibility, a higher position, and strong ‘in the background’ assistance, such as protection from other government branches’ badgering or avoiding frivolous regulatory treatment.

Likewise, relatives, family members, companions, schoolmates, residents, and war amigos working in government, banks, and other related offices became the family’s functional group of associated individuals. In addition, China’s social practice of correspondence then, at that point, permitted the organization to pervade all over, coming to through connecting to fill in each underlying opening and setting courses at each hub of the informal community (Kubíček, & Machek, 2019). Since the associations were related with the family chief, it was matchless and unfaltering and, in this manner, a wellspring of the upper hand.

The family additionally had a different method for getting and keeping up with the political associations, like marriage and kids’ marriage. Families with numerous youngsters could sort out for some of them to enter legislative issues and fabricate a commonly supporting organization to control the dangers emerging from immature establishments. In this course of action, the privately-owned company’s assets gave benefits to relatives in legislative issues or working for the public authority, and those relatives then, at that point, offered help inside the public authority for their families’ organizations.

Hong Kong

Beyond the People’s Republic, the Chinese Family Business (CFB) has distinguished itself as a unique and significant hierarchical organization. It has also been a significant backer of the success of East Asian enterprises that have come to dominate global business sectors such as textiles, electronics, and watches. Regardless of its importance, little work has been done to gauge essential aspects of the peculiarity. No quantitative experimental work has been done to date to look at the relationships between the traits that are believed to characterize the CFB and the business approaches that it embraces.

This poses important questions for future debates about the direction East Asian enterprises and economies should go and scholarly debates on the relationship between the association and its current situation. Following Michael Porter’s research in academics’ competitive advantage, industry pioneers across the district have been calling for a shift away from traditional East Asian business systems. The relation between situations and human resources can be determined based on the small size, limited expansion, low cost, and value proposition (EY Greater China, 2020). Instead, they have advocated for the acceptance of ‘redesigning’ approaches that would allow for the acquisition of higher edges.

For a long time in mainland China and Taiwan, a ‘formative state’ has offered help for ‘redesigning,’ helping Chinese firms to obtain substantial new abilities, particularly in hardware and semiconductors. Some Chinese family businesses in Hong Kong have grown into large transnationals, internationalizing their operations, expanding their degrees, and accessing higher-end organizations worldwide. These enhancements demonstrate that ethnically Chinese firms and business groups exhibit a wide range of vital decisions. At least a few firms owned and controlled by Chinese families are capable of variation, development, and critical revamping.

Nonetheless, very little is had some significant awareness of whether that variation is related to change in the traditional structures and administrative directions that have been credited to the CFB. A few eyewitnesses have contended that those structures and directions are appropriate practically to the ‘customary’ techniques that have been embraced before, yet mismatched to the ‘overhauling’ methodologies proposed. Most CFBs have traditionally had an advantage in a ‘shipper fabricating’ capability, which allows them to obtain reduced expenses and charges.

However, the characteristics that enable that competence may be antagonistic to a shift to a different type of methodology. Overall, redesigning is more than just a matter of changing business methods. Changes in the firm’s philosophy are also included. The CFB that overhauls procedures might not be the same as the CFB that uses a more traditional approach to content management. To be sure, sooner or later, during the time spent variation, it may stop to be conspicuous as the peculiar business structure that has drawn in such a lot of consideration.

While policymakers and business pioneers are essentially worried about ‘seriousness,’ the subject of redesigning likewise reflects more extensive issues in the academic writing on associations. Specifically, it may be viewed as a feature of the discussions on the connection between Asian familyism and the cutting edge business association and determinism versus voluntarism. The degree to which associations display human organization, rather than carrying not settled for them by their social, social, and monetary climate.

The Characteristics of Chinese Family Businesses in Hong Kong

The main point was that “familyism” is the foundation of a Chinese company. Chinese business succession observed in the Hong Kong enterprises shows that around 53 businesses have less formalization of the family-owned businesses (Hibbler-Britt & Wheatley, 2018). The theoretical constructs and resource base compare the cultural impacts of the family-owned businesses when the Chinese practice them in foreign countries. Therefore, founders and successors have minor job specialization than western or Japanese businesses. It is speculated that this was due to the familyism and paternalism associated with Chinese sociological characteristics. In the latter half of the 1980s, there was a surge in interest in Chinese business.

Redding saw the Chinese in other countries as a monetary culture and claimed a distinct soul of Chinese private enterprise. That soul is rooted in China’s psychological past and the organized concept of Chinese society. Because of three major influences, the privately-owned firm has remained the dominating hierarchical structure in that setting. These are uncertainty resulting from a general lack of confidence and ownership of abundance in social arrangements with a powerless practice of insurance for the property. Chinese also practice liberties, paternalism resulting from Confucian custom, and personalist promoting commercial processes.

While most Chinese families’ businesses are small, with limited scope and little creativity, a few are large, with extensive reach and linked to significant mechanical events. If CFBs can differ in those regards, they may likewise change in the degree to which they show the authoritative structures and administrative directions credited to them. Without a doubt, the two might be connected, which is the focal recommendation of this review. To conquer these limits, the current examination conceptualizes the idea of the CFB instead in an unexpected way. Instead of focusing on the Chinese family-owned firm as a distinct class, the CFB is viewed as a characteristic or a disorder with multiple sub-aspects.

Isomorphism, Strategic Choice, and Hong Kong’s CFB

The cycles that make up the CFB’s hierarchical features and business process can be viewed from various perspectives. These investigations focus on the CFB’s authoritative qualities rather than its commercial strategy, and they emphasize that its tendency is influenced by the foundations into which it is put. They also emphasize the ‘ideational’ (social, socio-mental, social, and intellectual) channels the CFB is influenced, rather than the ‘material’ ones (the specialized and financial prerequisites of productivity or hierarchical viability).

On the other hand, the Chinese emphasize the business procedures used by Hong Kong enterprises, arguing that the ‘traditional’ approach is based on cost control. Value management can be seen as a thoughtful and necessary response to the frantic postwar period’s material requirements. Hong Kong enterprises had to compete based on cost since they lacked physical, inventive, and brilliant people resources. However, they were outstanding with modest and highly persuaded work. They could not screen for change since they were geographically, socially, and etymologically separated from their business areas. As a result, they should have been adaptive such that changing economic conditions did not force them to incur costs they could not afford.

Notwithstanding those requests, they contrived a business ‘formula’ including adaptability and cost-based rivalry upheld by an appropriate association for its motivation. Creation proficiency and low costs were gotten by the nearby observing of tiny labor forces, completing straightforward, work concentrated gathering work, facilitated and constrained by relatives unencumbered by traditional designs and loyally adhering to the directions of a chief or mentor. Conditional effectiveness was obtained by utilizing organizations of unique interactions.

The dangers inherent with atypical far-flung business sectors were managed by maintaining a high level of transient concentration and confining venture to acquire widely usable resources that might be converted to elective uses if the market altered. At the yearly career expos, advertising exercises such as marking and ecological checking were eschewed favor of one-of-a-kind hardware manufacturer (OEM) and face-to-face selling. According to this viewpoint, the Hong Kong CFB’s business philosophy in the newly developed manufacturing area of the 1950s and 1960s was influenced by monetary ambitions rather than social factors.

While the conflict over culture and the conflict over productivity in setting provide different clarifications for the design of the CFB and provide a debate ground for market analysts and sociologists, they are not completely unrelated. Both could play a role. Furthermore, the conceptual or organizational features may significantly support the material goals, affecting authority viability. To be sure, contemporary institutional scholars studying East Asian economies have argued that “the institutional and specialized parts of conditions need not be at odds with one another. Yet, they do they need to be fundamentally unrelated; on the contrary, they can merge amicably in molding hierarchical structures.” Institutional game plans do not lead to a decrease in productivity or the appropriateness of hierarchical systems.’

The CFB’s constructs, directions, and systems can be regarded as the outcome of both conceptual and material variables without logical conflict. While both the cultural and productivity arguments can be accepted, they highlight two problematical points. The first is that they are deterministic. The CFB and its owners are regarded as benign automata displaying the pre-programmed content. As a result, independence and human office have no place in Asia’s state-run administrations and businesses. Despite the overwhelming discussions among Asian state-run administrations and businesses about the steps they should take to achieve future success, the examinations dedicated to elective prospects, and many Asian MBAs trained in essential administration. The emphasis on ‘isomorphism’ in the two approaches raises a second, closely related issue.

‘Serious isomorphism’ comes from familyism and Sinic culture’s shared objectivity as enterprises merge on the most sophisticated business systems, whereas ‘institutional isomorphism’ emerges from the typical objectivity of familyism and Sinic culture. Varieties are either ignored or considered abnormalities when attention is focused on the components of resemblance within company groups. Nonetheless, even a casual observation can reveal that significant differences in the number of Chinese enterprises, and these distinctions are worth considering. The deterministic viewpoint is not fundamentally unrelated to a more voluntarist view in which administrators apply tremendous independence and variety is noticed. One hypothetical structure that might incorporate the two is presented by the cutting edge form of the ‘essential decision viewpoint.

It was developed in its distinctive structure to fit in with the then-dominant functionalist notion that the climate deterministically dictates design and behavior through productivity considerations. It then emphasized human office and the ability of an organization’s ‘prevailing alliance’ to establish its current situation and make unencumbered decisions. However, just as the functionalist approach ceased to rule authoritative hypotheses, more subjectivist perspectives rose to the fore. The letter detailing the critical decision viewpoint has also refuted the contrary view that organizations and their occupants are openly willing to ‘authorize’ the climate as they see fit.

It recommends that the climate exists ‘out there, autonomous of the association. Both conceptual and material components in that climate give imperatives on associations’ independence, holding the ‘iron enclosure’ of isomorphism, which is integral to the contemporary institutionalist view. Be that as it may, rather than completely deciding the conduct of supervisors and associations, these powers set the ‘boundaries of decision’ inside which the association and its inhabitants have a component of self-assurance. To expand the focal allegory, the iron enclosure is sufficiently genuine. Still, it encompasses growth in the company, which is controlled by natural strain. The enclosure’s tenants have apparatuses they might use for a program of home improvement, augmentation, and, occasionally, movement.

This structure could help develop the CFB in Hong Kong’s manufacturing region. Both material and conceptual conditions were unusually encompassed in the horrific conditions of the 1950s and 1960s. As a result, the iron enclosure was small, and the potential for human office or crucial decision-making activities was tightly compelled. With a cost authority based on cheap wages and a way of life and foundations that were those of a poorly educated local area in an unflinchingly Chinese context, Hong Kong enterprises’ business system and authoritative structure were essentially constricted.

Fortunately, and contrary to popular belief at the time, the authoritative characteristics that had moved from the Chinese setting were sufficiently adjusted on the methods’ side. Together they formed an, in reality, fruitful ‘gestalt.’ It would be inappropriate and rather pitiless to discuss the ‘critical decisions’ taken by Hong Kong enterprises under those devastating conditions, considering the minimal scope of independence action. Regardless, such determinism only lasts as long as the climate remains closed-minded in material and mental capacities. If it turns out to be physically more ‘kindhearted,’ and the social constraints are eased, corporations will be able to practice a higher level of critical decision-making.

The material imperatives that hampered the choice of business approach in Hong Kong during the 1960s have fundamentally eased. The city’s physical and monetary resources have significantly increased, and its monetary frameworks have strengthened, so access to capital is no longer a problem. Lower transportation costs, improved correspondence developments, and higher levels of training have made it easier to examine far-flung corporate sectors. The growth of earnings in China has given rise to the beginnings of a ‘homegrown’ industry in which Hong Kong enterprises have a distinct advantage and a reputation for reasonably high quality. Compared to the period when their typical design was not determined, Hong Kong’s assembling firms have significantly more slack in the activity of critical decisions.

Similarly, as material constraints have been removed, higher levels of education, legal property protection, expanded correspondences, and notable collaboration with the rest of the world have slackened the social bonds to a crucial degree. This shift in decision boundaries has accompanied a flurry of strategic chatter ‘need’ for change and’ updating.’ Before the end of the 1970s, the assembly industry’s ability to compete globally was a source of concern, and consensus developed that significant change was required.

As a result, it was claimed that the financial objectives had shifted and that they were now similarly pressuring toward revamping. Nonetheless, before history could bear witness to the validity of that concern, the Chinese economy began to take off in the mid-1980s, allowing for the creation of an effectively endless stockpile of trim work and, as a result, giving the conventional formula a new lease on life. Hong Kong businesses found themselves in a two-tiered environment that has persisted. From one perspective, they are located in the high-wage, high-lease context of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (SAR), with its well-established legal and administrative framework. Rich, cosmopolitan, extremely gifted, high-cost, and highly stimulated population.

They are, nevertheless, physically, socially, and semantically close to China’s center area, where rents, incomes, and wages are low, foundations are immature, and the average level of knowledge is poor. Considering the material climate, the fundamental decisions taken under the terrible states of the 1960s remain accessible, but the range of options has widened. The requests for revamping have undoubtedly continued. According to a persuasive presentation in Hong Kong, traditional procedures have outlived their usefulness, and only updated tactics are possible. If such were the case, critical decisions would be hampered in any event, this time by financial strains of a different kind.

However, there is no clear evidence to support that contention. One study found no presentation differences between organizations that use the traditional methods and those that choose a level of revamping. To summarize the reasonable system adopted here, Hong Kong enterprises’ authority structures and business operations are partly influenced by the conceptual and material climate in which they operate. As a result, it is natural for them to exhibit some isomorphism. By the way, there is room for them to simply decide at a finer level, within the cutoff thresholds imposed by that climate.

Elective Business Strategies and the Characteristics of the CFB

According to the findings, Hong Kong enterprises have had the chance to practice a level of critical decision since the late 1960s. The standard features of the CFB were significant for the business formula they adopted to compete in far-flung business sectors. As a result, the notion is that there is a positive association between a firm’s display of CFB characteristics and its acceptance of traditional business practices. Because different systems require different asset demeanors, which are sustained by different authoritative aspects, similar attributes may be inappropriate and inhibit revamping. As a result, the opposing theory poses a negative link between CFB characteristics and the types of update processes that have been endorsed has been supported.

To put these broad guidelines to the test, examine which of the CFB’s builds are likely to have an impact on company strategy, as well as how they might be estimated. The wording was reevaluated to reflect the most remarkable and essential components of the CFB while also recognizing those CFB qualities that are depicted as affecting the accepted business systems. The following elements were chosen as a result of the interaction:

- The chief executive officer (CEO) predominance refers to how reliant the company is on a single best individual to make decisions. Every major investigation of the CFB, including Redding (1990) and Whitley (1992), recognizes it as an essential aspect of the authoritative structure. While it lowers the cost of independent direction, increasing the CFB’s productivity and adaptability, CEO strength is a barrier to updating. It limits the information base on which decisions are made and prevents the development of an expert administrative chain of command (Carney 1998b). As a result, the association’s ability to pursue operations that demand skills beyond the CEO’s experience is limited.

- Paternalism is how educational and patrimonial the CEO’s manner is — traveling about as a mentor, expecting people to recognize decisions, and anticipating that they should ask for advice. This structure is essential to the CFB’s ‘familyism,’ its most notable feature. Paternalism, like CEO strength, contributes forcefully to intensity as effectiveness and value authority while neutralizing the development of activities that demand a more outside direction, such as natural filtering, brand character advancement, or product offering augmentation.

- Organizing information refers to the informal sharing of data and business opportunities with other companies in the industry. This aspect of the CFB has been seen as its most significant strength. Typically frail, tiny enterprises have solid linkages with others to form a severe overall framework. Data organization in CFBs has also been compared to ‘adaptable creation organizations,’ which have been described as a ‘post-modern’ sort of contemporary organization (Mustafa et al., 2019). While such organizations have been lauded for their ability to achieve cost efficiency, it has also been claimed that they insulate businesses from data that originates elsewhere. As a result, while the organization strengthens current capacities, it is difficult for residents to develop new strategies to deal with rivalry.

- Organizational personalism in business is concerned with the extent to which personal connections are used to establish and support commercial contacts and the age of new business. In systems management, personalism provides a framework of commitment and correspondence built up over time through repeated interactions. Compared to the exchange costs associated with credit and provider capability, creation planning, and quality control caused by a progressive administrative system, such a framework boosts productivity by instilling trust and lowering exchange costs related to credit and provider capability, creation planning, and quality control. As a result, it focuses on cost seriousness. However, it also limits the number of prospective trade partners, indicating its failure to benefit from the larger globe.

- Short-termism indicates how much of the firm’s business planning and execution improvement effort is focused on the short term. Short-termism has been considered a vital component of the CFB, contributing to ‘methodology as hustle,’ enabling quick ‘spatial exchange,’ and laying the groundwork for the CFB’s formidable capacity to handle requests with short notice. Simultaneously, the receipt of a short-term skyline prevents the firm from investing in activities that require long-term funding and effort, such as enhancing brand character, developing climate-monitoring equipment, and expanding the product offering.

After identifying the builds used to depict the CFB, it is time to figure out which ones will depict the business methodologies they employ. For variable selection, three measures were used. To begin, the set of elements should include well-founded developments that have been demonstrated to have legitimacy and dependability in a variety of contexts, ideally in a perfect world in Chinese. Second, it should include a collection of well-defined features that may explain and distinguish between ‘traditional’ and ‘redesigned’ methods as they are discussed in Hong Kong and relevant in the specific current situation under consideration. Third, it should be smaller so that the data may be acquired without an undue burden on the responders.

Covering Speculation and CEO Progression in Privately-run Company Bunch

The corporate group’s substantial control and organizational system are based on a group of closely associated center actors, referred to as the “inward circle.” Individuals from Taiwan’s business groups’ internal circle coordinate gathering business by covering various gathering firms’ interests. The covering venture amongst proprietor supervisors demonstrates the number of interlocking investors among the many offshoots in a business group. A business bunch is a collection of initiatives linked together by a few center proprietor administrators’ covering ventures. As a result, examining the covering venture among key stakeholders is a critical task in understanding the activity of the company group.

Although most investors in a privately-owned firm group are the center proprietor administrators who are bolstered by particularistic relationships (such as family and previous friendly ties), there are still other minority investors in the top managerial staff within each member. With the opening up of capital markets and economic development in Taiwan and the extension and expansion of gathering, privately-owned firm gatherings may attract outside financial backers, resulting in a more dispersed and open shareholding structure. As a result, family proprietorship would be eroded, while the internal circle would grow.

Institutional developments in Taiwan between 1987 and 1993 triggered more institutional financial backers and across-group cross-shareholding, masking the gathering boundaries. The initial inward circle members would involve covered investor positions in several partners to achieve predominant control. While planning for succession, Taiwan residents would also entice various outside financial backers to join the group, ensuring that outside investors did not cross-shareholder the associates (Mustafa et al., 2019). The more severe level of covering speculation over the center proprietor’s chiefs in the privately-owned company bunch is, at the close of the day, a kind of chosen technique for the family to command over the business bunch.

Interlocking shareholdings among internal circle members contribute to a robust corporate group; in this view, a covering venture provides individuals with a tool to help them protect their control authority. When the amount of covering speculation inside a corporate group is high, there are more ordinary investors among the many subsidiaries, and other non-proprietor directors can barely contest the situation with the initial regulators. As a result, we believe that if the covering venture inside a privately-held corporate group takes on a more serious role, the chances of progression are reduced.

Family Control and CEO Progression in Privately-Run Company Bunch

Particularistic links between the center individuals in direction are unmistakable in the administrative structure of Taiwan’s business groupings, and they are linked with a level of centrality in navigation. Inside the inner circle, Chung (2004) classified particularistic links into four types of connections: familial connections, prior amicable connections, strangers with typical personalities, and outsiders. In most Taiwanese business gatherings, family ties are the most common classification. People’s shared credits in particularistic linkages provide durable connections and work through correspondence and trading.

One distinguishing feature of privately held businesses is that they emphasize personal power and a belief in self-direction. Social relationships in Chinese social hierarchies are organized in concentric circles, with kin at the center and strangers at the periphery. In Taiwanese commercial gathers, families are wary of those outside their family and connection group; as a result, they anticipate holding administrative positions in various gathering enterprises to maintain complete control. By placing relatives in crucial administrative positions, Chinese privately-owned company clusters ensure proper coordination and supervision.

However, with the expansion of the corporate group, the family must cope with maintaining a controlling share in the group. Relatives were never entirely involved in the internal circle due to changing institutional and economic situations. The higher the seriousness of relatives in administrative posts, the more control the relatives have over the gathering. Suppose more relatives hold key administrative positions within privately-run company gatherings. In that case, the family can maintain and settle in command of the gathering, and there will be no need to let the advancement occur. As a result, we recommend that the higher the degree of relatives as associate leaders inside the company group, the lesser the chances of growth.

The Directing Impact of Past Execution in Privately-Run Company Bunch

One of the reasons why experts have been interested in the growth of top executives for a long time is to answer whether or not the CEO’s appearance matters. If the top management has just symbolic value, CEO turnover will not bear the firm’s performance. However, if the top management has practical value, the previous execution of the business should be a significant factor in changing the company’s pioneer. Presidents are frequently chastised for poor performance, fired for inadmissible execution, and replaced by top executives expected to improve execution.

Without question, as company execution suffers from a few observational inspections, leader departure is more likely. Replacing a CEO who has had a poor performance is, by all accounts, a standard practice in all economic frameworks. Given the vast differences in corporate governance systems, the chances of CEO turnover in Germany, Japan, and the United States are comparable; the increase in the likelihood of turnover due to helpless returns and pay catastrophes is nearly identical in all three countries.

The results were predictable when progression recurrence was used as the dependent variable: low-performing firms had higher progression rates. While the general observation that inadequate earlier presentation is linked to development is encouraging, the link between CEO advancement and hierarchical execution is messy. To help us advance our understanding, the field has begun to emphasize execution as an arbitrator. According to the arguments presented above, a more significant level of covering speculation amongst proprietor administrators and a more considerable proportion of relatives as leaders of gathering firms are expected to have a lesser probability of CEO advancement.

Nevertheless, if the gathering is poorly executed, many internal circle people may question the occupying chief’s authority. Helpless gathering execution deals with force clashes and political skirmishes at the top of the corporate ladder, increasing the likelihood of CEO advancement. According to this line of reasoning, the timing of the gathering will affect the consequences of covering venture and relatives as leaders of gathering subsidiaries on the possibility of CEO advancement.

References

EY Greater China. (2020). How are family businesses in China planning for succession? EY US – Building a better working world.

Gagne, M., Marwick, C., Brun de Pontet, S., & Wrosch, C. (2021). Family business succession: What’s motivation got to do with it?. Family Business Review, 34(2), 154-167.

Hibbler-Britt L.M., Wheatley A.C. (2018) Succession Planning in Family-Owned Businesses. In: Gordon P., Overbey J. (eds) Succession Planning (pp. 75-87). Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

Kubíček, A., & Machek, O. (2019). Gender-related factors in family business succession: a systematic literature review. Review of Managerial Science, 13(5), 963-1002.

Mustafa, M. J., & Elliott, C. (2019). The curious case of human resource development in family‐small‐to‐medium sized enterprises. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 30(3), 281-290.

Mustafa, M., Elliott, C., & Zhou, L. (2019). Succession in Chinese family-SMEs: A gendered analysis of successor learning and development. Human Resource Development International, 22(5), 504-525.