Enterprise Integration Methods

It has been noted by some practitioners that over the last few years that there has been significant growth in the importance of enterprise integration. This fact is especially given the fact that many organizations are becoming increasingly reliant on information technology (IT) (Lam and Shankararaman 1).

This position suggests a need to ensure both business processes and technology systems are coordinated in a strategic manner. The increased reliance on IT provides a competitive edge though in some cases businesses require some level of IT to function.

In the past organizations the required IT applications developed these as standalone systems. Such systems were often developed to address specific functional domains such as sales, marketing, personnel, manufacturing and billing (Lam and Shankararaman 2). The result of this individual approach to systems design resulted in several hundreds or even thousands of separate IT applications.

As business evolved there emerged a need to integrate these separate IT applications to be evolved to support additional business requirements (Lam and Shankararaman 2). For example, the need to automate the transfer of customer details from a sales system to a billing system.

For this reason integration of IT applications was expensive and time consuming. This piecemeal integration approach led to organizations facing problems owing to a massive application with several custom interfaces. The maintenance of such systems was expensive and thus created the interest for enterprise integration (Lam and Shankararaman 2).

Enterprise integration can be defined as strategic consideration of processes, methods, tools and technologies associate with the achievement of interoperability both within and external to the enterprise with the goal of enabling collaborative business processes (Lam and Shankararaman 2).

This integration is not only about technology but also considers business processes that cut across business applications. For this reason enterprise integration is business driven. Enterprise integration involves process, service, application, data and presentation integration. There are a number of approaches that have been suggested for enterprise integration including batch, point-to-point, broker-based and business-process integration (Lam and Shankararaman 13).

GERAM

In response to the need for enterprise integration a variety of integration approaches have come in to existence. Among these is the Generalized Enterprise Reference Architecture and Methodology also known as GERAM.

The basis of this approach is the creation of a general architecture including tools, methods and models required to develop and maintain the integrated enterprise (Bernus, Nemes and Schmidt 23). Such tools are supposed to be useful in integration a single enterprise or even a network of enterprises. The GERAM framework is thus considered a suitable solution for all types of enterprises.

The general approach used in the framework suggests previously published architecture can maintain identity while identifying through GERAM (Bernus, Nemes and Schmidt 23). The GERAM framework is meant to unify methods from various disciplines such as management science, industrial engineering, etc., making them useful as a unit (Bernus, Nemes and Schmidt 23).

The most noteworthy aspect of the GERAM model is the fact that it provides the ability to unite enterprise integration efforts. This is due to the fact that GERAM allows for integration of models based on products with those based on business processes (Bernus, Nemes and Schmidt 23).

ZACHMAN EAF

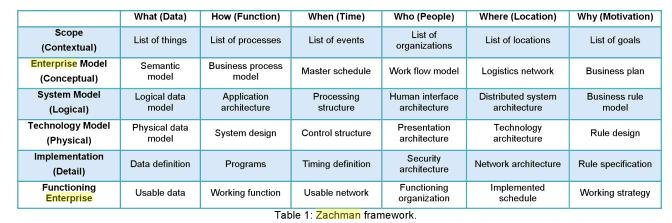

This approach was designed by John Zachman in the 80’s and focuses on the architectural framework based on several functional components (Radaideh and Al-Ameed 48). This model is based on a two dimensional framework and suggests the problem of enterprise integration can be tackled by separation of concerns.

The use of the two dimensional framework allows the decomposition of the problem into a number of distinct partitions. Once this decomposition has been achieved it becomes possible to address the finer issues in relation to a specific partition (Hesselbach and Herrmann 544).

This framework was designed to describe any idea that difficult to understand. The model is widely used for enterprise architecture modeling and consists of a 6X6 matrix (Hesselbach and Herrmann 545). Through this framework it is possible to capture different aspects of a given sustainability standard. Each cell in the model contains a description of what information should be captured and how it should be expressed. For this reason models in separate cells can exist independently though this does not infer they have no relationships.

Due to its compartmentalized approach this framework is widely used for documentation and/or development of enterprise wide information system architecture (Wout, Waage, Iartman, Stahlecker, and Iofmann 162). The use of traditional practices used in architecture and engineering form the basis for this framework.

As a result of such a background, the framework’s vertical axis adds many perspectives in relation to the overall architecture. On the other hand, the horizontal axis of the framework classifies artifacts related to the architecture. The framework targets the creation of wholesome independent artifacts which in turn contribute to the completion of the whole integration process (Wout et al., 162).

FEAF

This approach was originally developed to integrate the Federal Enterprise Architecture (FEA) with various to enable various Federal Organizations and their respective architectures (Saha 3). It was initially designed as a business based framework that would facilitate efforts to transform the U.S. Federal Government to one that is citizen based, results oriented and market based.

This framework is supposed to provide an approach for identification, development and specification of architecture descriptions of high priority areas. The establishment of such a framework gives consideration to core components such as architecture drivers, strategic direction, and target architecture, among others (Saha 3). These components were found important to the development and maintenance of the FEA.

The FEA target is the creation of a Meta architecture framework that will allow interoperability between independently developed, maintained and managed architectures (Goikoetxea349). The framework defines expected principles that govern interoperability, conformance and migration that are used across the Federal government.

It is believed that through this FEAF mandate the Federal government can promote sharing of information, encourages development of enterprise frameworks within FEAF guidelines and promotes efficiency (Goikoetxea349). This approach comes with a number of advantages such as economies of scale through sharing of services, improved consistency and ease in capture and dissemination of elements (Goikoetxea349).

DODAF

This approach also seeks to standardize the methods and processes modeling of large government based organizations. Just as FEAF serves the US Federal government, this approach targets the Department of Defense (Blokdijk 24). This framework seeks to integrate systems such as those concerned with weapons, information systems dealing with procurement and deployment, consolidation of various sub agencies, unification of organizational goals and conducting global operations based on a single command system (Blokdijk 24).

Given that such tasks are often large and complicated there is a need to have in place a defined systems framework to promote cohesion throughout the organization. The system is unique in that it offers a variety of architectural views that complement all major initiatives of the organization (Blokdijk 24). The architecture is designed to serve military operations as well as civilian operations. The framework provides a set of standards, specifications and technologies that strongly promote inter agency cooperation and seamless teamwork.

The framework is based on the premise that any architecture can be described in three views namely, systems view, operational view and technical view (Goikoetxea 287). The operational view describes the participants and the information they may require to exchange. The systems view describes hardware and software requirements needed to complete the operations. The technical standards view lists the interface standards and other rules that the system must satisfy (Goikoetxea 288).

The architecture is built on the philosophy that architectures should be built with their purpose in mind. In addition to that, architectures should facilitate and note impede communication between people. It is also based on the principle that architectures should be readable and allow integration of multiple architectures. Lastly it is believed that all architectures should comply with the framework sufficiently to enable the achievement of the first three principles (Goikoetxea 288).

Based on these above principles architecture description according to DODAF is a six step process. The first step is to determine the use of the intended architecture. The second step is determination of the scope of the architecture. The third step is determination of characteristics to be captured. The fourth step is the determination of views and products to be constructed. The fifth step is construction of recommended products. The final step is the use of the architecture for the intended purpose (Goikoetxea 289).

Conclusion

In the course of this report several approaches to Enterprise Integration have been discussed. The main reason that Enterprise Integration has become a matter of concern has been traced to the increased reliance on Information Technology by many businesses around the world (Lam and Shankararaman 1). In light of this position it becomes apparent that there is a need to integrate these standalone systems to better facilitate information exchange.

In the attempts to integrate enterprises some government agencies such as the US Federal Government and the Department of Defense have established frameworks to facilitate integration (Blokdijk 24).

Whereas such frameworks have been established and can be used by both government agencies and civilians, they come with the disadvantage that they also suggest the creation of additional enterprise integration frameworks (Goikoetxea 289). This position is not very favorable given that the proliferation of frameworks appears to mimic the scenario that saw the proliferation of thousands of standalone systems.

Given that proliferation of enterprise integration frameworks does not appear a suitable solution it appears there is a need for a generalized framework which can serve the needs of all users. For this reason it would appear that the development of GERAM is a suitable and lasting solution to the problem.

The basis of this approach is the creation of a general architecture including tools, methods and models required to develop and maintain the integrated enterprise (Bernus, Nemes and Schmidt 23). Such tools are supposed to be useful in integration a single enterprise or even a network of enterprises. The GERAM framework is thus considered a suitable solution for all types of enterprises.

Works Cited

Bernus, P., L. Nemes, and G. Schmidt. Handbook on Enterprise Architecture. Berlin: Springer, 2003. Print.

Blokdijk, Gerard. Enterprise Architecture 100 Success Secrets – 100 Most asked Questions on Enterprise Architecture Definition, design, Framework, Governance and Integration. Brisbane: Emereo Pty Ltd., 2008. Print.

Goikoetxea, Ambrose. Enterprise Architectures and Digital Administration: Planning, design and assessment. Danvers, MA: World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd., Print.

Hesselbach, J., and C. Herrmann. Glocalized solutions for Sustainability in Manufacturing. Berlin: Springer, 2011. Print.

Lam, Wing Hong, and Venky Shankararaman. Enterprise architecture and integration: Methods, Implementation and Technology. Hershey: Information Science Reference, 2007. Print.

Radaideh, M. A., and H. Al-Ameed. Architecture of Reliable Web Applications Software. Hershey: Idea Group Publishing, 2007. Print.

Saha, Pallab. Handbook of Enterprise Systems Architecture in Practice. Hershey: Information Science Reference, 2007. Print.

Wout, Jack, Maarten Waage, Herman Iartman, Max Stahlecker, and Aaldert Iofmann. The Integrated Network Architecture explained: Why, What, How. Berlin: Springer, 2011. Print.