Introduction

Globalization is a process known to be boundary-spanning, originated and designed through the centuries to create a multicultural world. From the time trade emerged between cultures, their boundaries were partially spanned. It would seem that the cultural legacy of humanity was an indispensable and logically integrated part of the process – and it was, up to a certain point in history.

When exactly culture became an object of business is difficult to pinpoint – but the inarguable reality is that ownership has firmly established itself within the domain of globalized culture and art. Globalization, as experts say, is an extended version of private (or collective) ownership, primarily because globalization relies on interconnected economic practices worldwide. The main objective of such practices, obviously, is revenue; ever since humans realized objects of excellence could be traded, the fate of art worldwide was determined.

With respect to trade, creativity has become an integral part of business, considering the dynamic environment that makes up the global economy. However, it is implied that the spread of art is brought about by the urge for a multiculturalized global community – or so it seems. Indeed, any half-competent analyst can observe the demands that globalization puts on artists. The latter are urged to create – vigorously, prolifically, and independently, thus rejecting the culture they were born to.

These processes that harness creativity seem to result solely from the sphere of marketing, not least because creative business practices encourage individuality and uniqueness regardless of cultural background. It seems that noble art, in the global context, functions as a mediator between cultures, enriching both the art and those who contemplate it. This paper is aimed at asserting that noble art – as opposed to mass art and business creativity – is actively incorporated into the global art canvas with corresponding capitalist practices. Because global culture is that of capitalism, it urges people to create, simultaneously making use of their creative energy and incorporating art through the media of replication (e.g., movies and remakes) and trade to make profits.

Creative and Rebellious

As mentioned, in its perpetual hunt for creative output, globalized business assures each individual creator of their uniqueness. When globalization is subject to the corporate world, originality, quirkiness, and general non-conformity become valuable assets. Similarly, universal culture urges creators of noble art to regard themselves as rebels. The inspiration of contemporary artists is fostered accordingly. In a similar vein, those who are long gone can only be popularized and romanticized as rebels.

A good example of such romanticization would be Jang Seung-eop, also known as Owon. His life and career fell within the Joseon Dynasty in Korea (1843-1897). He is notable for being just about the only painter of the time holding a position at court. He painted in the genre of abstract Chinese landscapes and went into animalistic painting, for instance, “Gunmado” (“Herd of Horses”).

His other works belong to a separate branch of Korean painting influenced by the downfall of the Ming and the formation of the Qing dynasty, wherein Korean artists were obliged to search for national artistic identity. In spite of his influence and achievements, Owon was widely known within Korean culture but not outside it – until his life was reconceptualized in “Chihwaseon” (“Painted Fire”). The movie that won an award in Cannes has brought him recognition.

Rebellion, at its core, is the instant when a creative soul is acting out its inner (darker) impulses and puts into practice thoughts that are taboo, stigmatized, forbidden. The film presents Owon’s life as the painful process of creation which is impulsive and, at times, repulsive. The love that is likely to lead to mésalliance, excessive alcohol consumption, and the artist’s self-destruction are depicted as forms of rebellion. Although it is not clear at times what exactly the artist rebels against, such a depiction both draws the public’s attention to the artist’s personality and assures the viewer that everyone, in spite of themselves, can be creative.

Creative Again

The search for creativity sometimes becomes frantic, although a savvy contemplator might just as well wonder which is more valuable: the result of creativity, or the sheer volume of it. With contemporary artists and ad makers, it is the bulk of creation that is valued. In other words, the ability to create quickly and (if possible) uniquely is an asset – which is the reason each individual artist is actively assured of their unsurpassed potential. If creative energy cannot be milked from the artist because they are deceased, the contemporary globalized culture refers to replication and reproduction.

Hishikawa Moronobu is mistakenly known in popular sources as “the father of ukiyo-e,” but, as a matter of fact, he was not. He is, however, renowed for his contribution to and impact on the popularization of the genre. Partially, his (or the genre’s) influence is visible in the canvases of the Impressionists, including van Gogh. However, the artist’s works did not become truly globalized until the 1940s, when “Mikaeri Bijin” (“A Beauty Looking Back”) was issued in the form of postage stamps. The reproduction of the painting triggered viral stamp collection hype, but also gained the long-deceased painter and his “Beauty” worldwide recognition.

The painting and the motives hidden in it have been globalized and contemporized by various media to the present day. At that, the overarching principle of reconceptualization lies at the baseline. Before the overwhelming stamp hysteria of the 40s, the “Beauty” was recreated by Tadaoto Kainoshô under the same name in the late 1920s. The artist complimented the timeless work by Moronobu, but used the nationalistic nihonga style to recreate what was produced in ukiyo-e.

Another, and somewhat cruder retake on the “Beauty” came in the form of a video clip by the girl-band “Morning Musume.” The song in question is entitled “Mikaeri Bijin;” the lyrics feature the motifs of the floating world, and the female protagonist is wearing a red kimono with a green obi; she is also filmed looking over her shoulder. Incidentally, the clip was first streamed in 2014.

The replicas and copies can communicate hidden messages that would take some analysis (e.g., “the floating world” in the song lyrics can refer to the art and the world of show business). Their primary purpose, however, is to reveal the essence of an object of excellence. Repin’s “Barge Haulers on Volga,” for example, was appraised by fellow artists and writers as the foundation of Russian realism, a switch of focus to the working class as subject matter, and a masterful rejection of academic standards.

To the broader public and the world outside Russia, the painting was made known in the form of Finnish political cartoons focusing on the idea of social inequality and the working class “hauling” the upper crust. Such is the purpose of replication: simplifying the myriad ideas embedded in the object to reveal its essence. In the globalized capitalist culture, the wisdom of the human legacy is communicated in a simplified form, with a view to gaining a broader audience – and bigger revenues.

Creative and Profitable

With this idea in mind, it does not take much introspection to see the main point in capitalist globalization – profit. Adaptations and reproductions (the postage stamps, cards, t-shirt prints, etc., featuring “Gunmado,” “Mikaeri Bijin,” and “Barge Haulers”) are profitable for those owning the copyrights. Apart from that, the original paintings are sold at auction, and the highest-quality digitalized copies of them are bought by – and from – digital galleries.

The question as to whether globalized culture really values the products of creativity or just the fact of it can be, thus, answered in simple terms. Creativity and creation lie in the realm of genius, and emerge essentially from the space-time in which they were produced. In turn, globalization, capitalism, and sometimes the artists themselves transform creations into objects of trade.

The geniuses mentioned above, namely Repin and Moronobu, both marked the emergence of new styles in painting: realism and ukiyo-e, respectively. As another example, the contemporary, and the most acknowledged, Chinese artist Qi Baishi developed a unique style based on traditional Chinese principles, adding a personal touch of playfulness. Repin’s and Moronobu’s works, as well as that of Owon, were subject to social and political changes they witnessed at varying times: the social injustice of czarist Russia, the harsh economic conditions in Japan, and the nationalist attitudes in Korea.

Baishi was witness to the rise of the Soviet-Chinese Communist alliance; although communist motives are not traceable in his works, they were immensely valued in the USSR. What capitalist globalization does is put creativity on the conveyor belt and reproduce it massively. Conceivably, this is done for the sake of mass enlightenment but, de facto, the power of creation is acknowledged insofar as it can be sold. Artists such as Moronobu sometimes facilitate the process of art trade by making use of printing and mass replication of paintings.

Other artists, e.g., Repin, have their masterpieces sold, exhibited, and resold. Still other creators – Baishi, for one – become best-selling painters in the US, and have their portraits issued in postage stamp formats across the USSR. The process of art globalization is indispensable from the globalization of the market; it is evident that global culture fosters the same hopes and imposes the same demands as global business.

Conclusion

One can argue that noble art, even globalized, does not lose its nobility for good. On the contrary, globalization lets the world contemplate what would otherwise fade into a single culture’s history. However, the globalized culture’s practices imply that, in the first instance, a non-creative person will succumb, like Owon, to the sins of flesh and mind, while a creator will flourish. In the second, the public mindlessly indulges itself in the timeless objects of excellence, while global capitalist culture stirs the hype in search of new creative output. Thus, art globalization overrates individualism and gauges creations by the profit they bring. While multiculturalism is essentially a good thing, the market-like nature of it hints at something utterly troubling.

Entries

- Gunmado

- Jang Seung-eop

- Joseong Dynasty, ca. 1843-1897

- Ink on paper

- Literature: Yi, Pak, and Yun, 2005.

It is the paintings like Owon’s “Gunmado” that often go unnoticed in literature devoted to artistry – and yet leave the contemplator enchanted. The lines and texture of the painting convey the dynamics, the sensation of speed, and the sheer power of animals.

The painting is not frequently featured in popular sources; nor does the artist often come to light in literature or press. What is known about the painting is that the title can be translated as “A Herd of Horses” or “Men and Horses,” which is arguable. Nevertheless, if the latter translation is accurate (and even if it is not), the speed, anger, and ferocity of the animals can be seen in parallel with the life of a person. One such person could be Owon himself.

The explicit drama and recklessness are vividly expressed in the painting: the lines of the horses’ bodies, the arch of the necks, and the flying manes are slightly smudged. The legs are outlined schematically, which also conveys speed. The drama causes an association with the movie “Chihwaseon” wherein Owon’s life is depicted as a maddening struggle. In the award-winning movie that has raised global awareness about the artist, his creative personality succumbs to the pleasures of the flesh, leading him to self-destruction. His downfall is similar to the flight of the horses: blind, disoriented, and unthinking.

Owon is best known for his landscapes and allegories common in Korean painting of the Joseon Dynasty: longevity, trickery, wisdom, etc. Paintings such as “Gunmado” are often overlooked – but on second thought, they just might implicitly depict the whole point of the artist’s work and life.

- Burlaki na Volge (Barge Haulers on the Volga)

- Ilya Yefimovich Repin

- 1870-1873

- Oil on canvas

- H 131 cm, W 281 cm

- State Russian Museum

- Literature: Parker and Parker, 1991.

“Barge Haulers” is a depiction of working men dragging a boat upstream, harnessed like Shire horses. A representation of Russian social reality of the time, the painting was extremely popular both within Russia and outside of it.

The postures and the colors of ragged clothing and sunburnt skin –dark, despite the fair weather – give the overall impression of weariness and exhaustion. The only splotch of light and the focus of the canvas is the young person in the center, who appears to rebel against the hard labor. He is trying to take off his harness – but tentatively; his fellow burlaks do not pay attention, which conveys a sense of hopelessness.

It is worth considering the discrepancy between the hard labor of the haulers and the peacefulness of the upper-class households on the Volga, to acknowledge that, at the time, the painting was quite groundbreaking. The conflict of the social atmosphere in which the painting was produced is expressed through the rejection of an academic standard (which is indicative of Itinerants) and the subject matter (attributable to the realist movement). At the same time, the painting shows no sign of pity or complaint, demonstrating reality as it is.

“Barge Haulers” drew public attention to the nagging social issues of the time and received much attention. The painting was widely exhibited in Europe. Apart from that, it was frequently reproduced in the original format and in the form of cartoons satirizing the socio-political atmosphere during Repin’s lifetime, and long afterwards.

- Mikaeri Bijin (Beauty Looking Back)

- Hishikawa Moronobu

- Edo period, 17th century

- Color on silk

- H 63 cm; W 31.2 cm.

- Tokyo National Museum

- Literature: “Hishikawa Moronobu.”

“Beauty Looking Back” tells a story of subtlety and discretion, which is preferred to outright, aggressive beauty in Japanese culture. The master and one of the early proponents of ukiyo-e (“floating world”) Hishikawa Moronobu produced an original drawing before he did his best to have woodblock printing popularized.

The “Beauty” is a depiction of an Edo girl in colored national clothing, caught at the moment of looking over her shoulder. The depiction of women’s beauty was one of the common motives in ukiyo-e, which sometimes concentrated on portrayed groups and erotica. The style is attributable to that of early ukiyo-e, which, despite the texture and color, bears an almost elemental disposition. The lines of textile folds are schematic, and the position of the girl’s figure depicts the brevity of the moment the artist rendered her.

Among the plethora of Moronobu’s works, “Beauty” stands out as the one to have caused a sensation in the world in the aftermath of WWII. The postage stamps with the “Beauty” on them caused a massive fever of stamp collecting, and was dispersed all over the world. More importantly, the picture of Edo girl as a symbol of Japanese art legacy was reconceptualized in other art works through various media. The genre of ukiyo-e was previously known in Europe: the motives of the floating world can be traced in the works of the Impressionists. The mass production of stamps, however, triggered the extreme popularization of the genre, which is one of the mechanisms of art globalization.

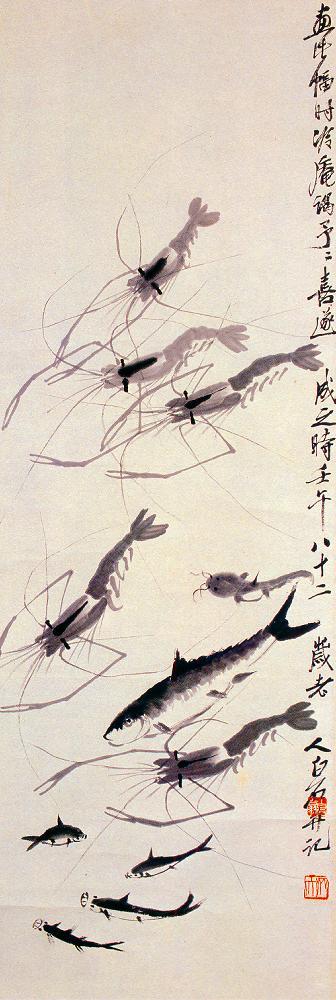

- Fish and Shrimp

- Qi Baishi

- 1943

- Ink on paper

- H 101 cm; W 34 cm (hanging scroll)

- Orient Gallery, New York

- Literature: Gerwing, 2014.

Xu Beihong is known as the painter of horses, while Qi Baishi is most famous for his shrimps. One of the three best-selling painters in the US, Baishi is the epitome of how oriental, particularly Chinese painting, can become globalized.

Apart from other subjects, such as peaches and chickens, Master Baishi’s favorites were shrimps, crabs, and other marine fauna. He produced the bulk of his shrimp paintings during the later years of his life. He gravitated towards minimalistic painting and calligraphy, and it was during the 1940s that his brushwork ascended to genius. In several lines, he managed to convey the shrimp and fish so masterfully that the contemplator can see and almost feel the water around them.

His success could be attributed to his total avoidance of any influences of the West. Still more importantly, Baishi managed to refrain from becoming a political painter, despite the storm of praise from both the Soviet and Chinese Communist parties. Surrounded by art where socio-political messages went primarily to aesthetic subject matter, he revived a multitude of traditional Chinese techniques and simple subjects and added a fair amount of personality to his painting.

The world’s search for authenticity was over when Baishi was discovered and instantly acknowledged – in his later years. The paintings such as “Fish and Shrimp” were often the objects of unfair trade and forgery – which is only to be expected, since a 35×35 cm album leaf with two shrimp paintings can be sold for $189, and more. His paintings convey the essence of Chinese tradition, and deviate from political messages, which might explain their immense value.

Bibliography

Carroll, Noël. “Art and Globalization: Then and Now.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 65, no. 1 (2007): 131-143.

Gerwing, Jonas. Between Tradition and Modernity – The Influence of Western European and Russian Art on Revolutionary China. Stoughton, WI: Books on Demand, 2014.

Haiven, Max. “The Privatization of Creativity: The Ruse of ‘Creative Capitalism’.” Dissident Voice. 2012.

“Hishikawa Moronobu.” New World Encyclopedia. Web.

Laibman, David. “Editorial Perspectives: Art, Science and Globalization.” Science & Society 73, no. 4 (2009): 445-451.

Parker, Fan, and Stephen Jan Parker. Russia on Canvas: Ilya Repin. University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 1991.

Yi, Hyon-Hui, Song-Su Pak, and Nae-Hyon Yun. New History of Korea. Seoul, Korea: Jimoondang, 2005.