Biography

One of the 20th century’s greatest photographers Gordon Parks was born in 1912 to the family of African-American farmers in Fort Scott, Kansas. Ever since his early years, Parks used to be exposed to racism, which partially explains why he could not obtain a formal college diploma.

After the death of his mother in 1926, Parks was forced to move to Minneapolis, where he made a living by affiliating himself with a number of odd jobs, such as the job of a ‘porter boy’ in the town’s gentlemen-clubs. While working hard, in order to ensure his physical survival, Parks nevertheless proved himself resourceful enough to take an interest in many pursuits, which at the time were considered being solely reserved for White Americans, such as playing piano.

Nevertheless, it was specifically Parks’ budding fascination with photography, which had set him on the path of becoming one of the most socially prominent African-Americans of all times. In 1938, Parks purchased his first camera and started to apply an active effort in turning this fascination into the mean of supporting himself financially.

Even though that initially, Parks strived to gain recognition as a fashion photographer, it is specifically by securing jobs with the Farm Security Administration (FSA) in 1939 (which provided him with the task to photograph the social effects of the Depression in America) that he was able to make himself a name.

People started to regard him as being not only extremely talented but also a ‘visionary’ photographer. It is namely this particular phase of Parks’ professional career, which is now being commonly referred to as having been the most discursively significant. This is because, through the years of 1939-1942, Parks did not only succeed in photographing the sheer scope of social injustices in America, but he also managed to expose many of these injustices, as such that had been reflective of the American society’s racial intolerance.

In 1948, Parks became the first Black photographer, hired by Life magazine. While working for this magazine well into the sixties, Parks was able to make the photographic records of what accounted for the era’s most important socio-political developments – specifically those associated with the rise of the Civil Rights movement in America.

It is specifically due to what were Parks’ professional activities, during the course of the earlier mentioned historical period, that we can now enjoy the exceptionally well-photographed images of Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, and Mohammed Ali. Simultaneously, Parks was involved in a number of other intellectually stimulating activities, such as writing poetry/novels and composing music. His most well-known autobiographical novels include 1963 The Learning Tree and 1966 A Choice of Weapons.

Ever since the early seventies, Parks also became involved with the movie-industry – the year of 1971 saw the release of Shaft (film), directed by Parks, which is now being discussed as such that originated a whole new cinematographic genre/style of blaxploitation. Throughout the course of the eighties, Parks directed a few documentaries, concerned with the Civil Rights movement, and composed the libretto to the opera Martin, dedicated to the memory of Martin Luther King.

During his life’s latter stages, Parks continued to apply a great effort in promoting the concept of interracial tolerance in America, while coming up with public speeches, on behalf of America’s socially disadvantaged populations, which had won him a number of honorary awards from both: The Federal Government and the country’s most prestigious universities. The world’s most famous African-American photographer died in 2006 from cancer (Mitchell, Martin-Hamon and Anderson 27).

Examples of photographs

The foremost feature of Parks’ photographs is the fact that, while being taken in an unmistakable realist manner, they emanate the strong spirit of humanism. The validity of this statement can be well explored in regards to probably the photographer’s most famous photo of Ella Watson (janitor) standing in front of the American flag inside of the FSA building.

What is being particularly noteworthy about this photo is that it prompts onlookers to consider the possibility that, working as a janitor, was not the photographed woman’s ‘true calling’. The reason for this is apparent – Watson’s very appearance suggests that she happened to be a thoroughly intelligent woman.

The fact that she is being depicted wearing glasses strengthens this impression even further. Thus, while being exposed to this photo, people cannot help experiencing the sensation that there is something inheritably wrong about the situation with an intelligent Black woman working as a janitor, which in turn leads them to conclude that she must have been forced to stick with this job by some external circumstances.

The American flag in the background symbolizes these external circumstances. Apparently, Parks wanted to emphasize that it was due to the policy of racial discrimination (which was enacted in America during the course of the thirties) that African-American women, such as Watson, could not even dream of a social advancement.

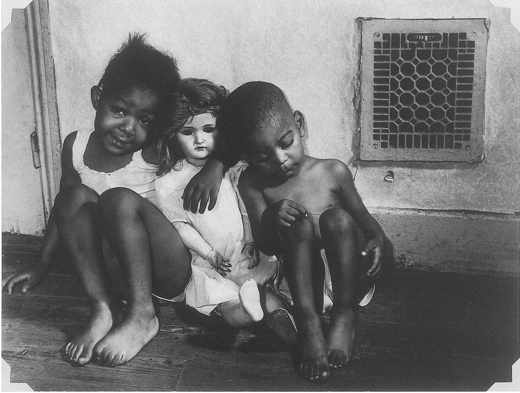

The motif of racial discrimination is also contained in the Parks’ photo of two Black kids playing the doll of a White girl.

There are two discursive aspects to this photo. First, the fact that Black children are being forced to play with this pale-skinned doll suggests that they were spared of an opportunity to play with a Black doll. The reason for this is simple – at the time when the above photo was taken (the late thirties), there were no dark-skinned dolls manufactured by the American toy industry.

This is because, during the course of this period in American history, the country’s Blacks were not considered fully human, which is why they used to be encouraged to mimic the lifestyle of Whites – playing with White dolls, was meant to make Black children emotionally comfortable with their future status of second-class citizens.

Second, the doll’s unemotional (cold) facial expression stands in a striking contrast to the facial expression of a Black kid on the left. This contrast’s symbolism is quite clear – apparently, Parks wanted to promote the idea that it is in White people’s very nature to regard African-Americans inferior, which is why it is wrong to believe that Whites would be willing to treat brothers with dignity, unless they are being forced to do so out of fear.

Nevertheless, it would be wrong to suggest that the objective value of Parks’ photographic masterpieces reflects the author’s tendency to expose racist injustices within the American society in a necessarily subtle manner. Quite on the contrary – Parks never skipped an opportunity to document even those instances of a racial discrimination in America that have been directly sponsored by the state. The photograph below validates the legitimacy of this suggestion.

On it, we get to observe a Black girl drinking out of the water-fountain, designated ‘colored only’, with the water-fountain designated ‘white only’ being only a few inches away. Given the ‘poodle skirts’, worn by two Black ladies on the right, we can well assume that this photo must have been taken during the course of the fifties in one of the America’s Southern states, where the so-called ‘Jim Crow’ laws enjoyed the legislative legitimacy well into the early sixties.

It is needless to mention, of course, that this photo can be well discussed in terms of a social commentary. It appears that Parks wanted to prompt contemporary Black onlookers to consider something that they have not been taught in schools, ran by White Bible-thumpers – namely, the fact they had very few reasons to remain loyal to the state, which was willing to go as far as denying their basic humanity, simply because they happened to have a dark skin.

Therefore, it is fully explainable why, as time went on; Parks was growing increasingly distanced from the idea that African-Americans simply had to continue applying an effort into trying to make Whites more racially tolerant, as Martin Luther King used to insist. Apparently, during the course of the sixties, it started to dawn upon Parks that, contrary to what King was suggesting, civil rights are not given but taken.

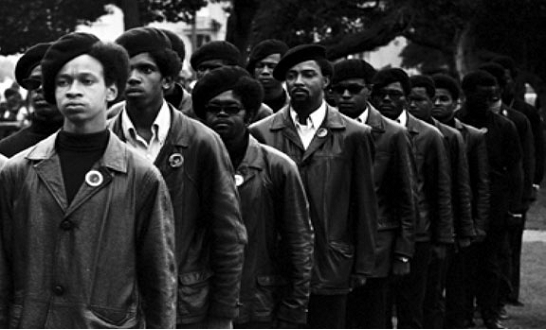

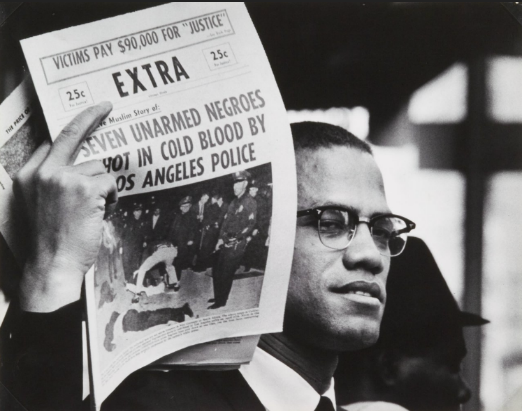

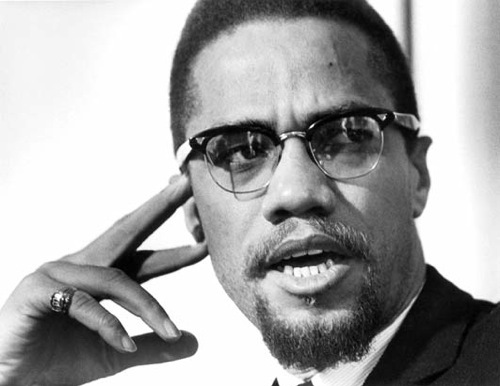

In its turn, this explains why through the sixties Parks was becoming progressively fascinated with the Black Panther Party, in general, and with the character of Malcolm X, in particular. The fact that Parks used to spend long hours, while photographing the party’s political rallies, headed by Malcolm X, validates the full soundness of this suggestion.

There can only a few doubts as to the fact that there is a strongly defined social commentary to the above photos, which can be summarized as follows: African-Americans have grown powerful enough to take a direct action against their oppressors.

As these photos imply, such an eventual development occurred due to African-Americans having succeeded in making the traditional ‘instruments’ of White people’s racial domination (their efficiency in self-organization and their intellectual capabilities) to serve the purpose of Black people’s liberation. This is the subtle symbolism of Parks’ photos, which feature Black Panthers standing in columns and Malcolm X touching its temple with his finger.

At the same time, however, it would be quite inappropriate to suggest that there are solely racial undertones to how Parks went about photographing the surrounding reality. Being a true humanist, Parks used to make a deliberate point in exposing the very essence of people’s existential anxieties – regardless of what happened to be the specifics of the photographed individuals’ racial affiliation. In this respect, the photo below is being especially illustrative.

Even though that, formally speaking, this photo simply depicts three blood-related females (a grandmother, a mother, and a daughter) that live in the same household, it in fact encourages viewers to contemplate on the shortness of one’s life. This is because the depicted characters allow onlookers to have a three-dimensional glimpse into the process of aging. The photo’s humanist appeal is quite apparent – once people realize the shortness of their lives, they will be more likely to try to make these lives count, such as by the mean of contributing to the well-being of a community, for example.

Personal reflections and reactions

I personally have always been a great admirer of Gordon Parks. The rationale behind this suggestion can be summarized as follows:

1. Parks contributed substantially towards the process of African-Americans becoming the masters of their own destiny. It is not only that Parks succeeded in exposing the subtle and direct manifestations of White racism, which helped the brothers to adopt a proper approach, while addressing it, but his photographic masterpieces also resulted in prompting the representatives of socially underprivileged racial minorities in America to take a full advantage of their existential potential.

One of the reasons for this is that, even though many of the depicted ‘colored’ characters in his photos appear to have suffered from poverty and racial discrimination, there is an unmistakable aura of a perceptual optimism to them. Hence, a subtle message, conveyed by most of the Parks’ photos – despite the fact that Blacks/minors do often experience social/racial oppression, they nevertheless possess something that their oppressors no longer have – a psychological and biological vitality.

In this respect, Parks proved himself a true visionary – as of today, African-Americans have effectively ceased being ‘hunted’, while gradually assuming the role of ‘hunters’. The validity of this suggestion can be easily illustrated in regards to what account for the realities of today’s living in America, associated with the process of Whites growing progressively weakened, when it is being only the matter of time before they themselves become the representatives of the one of many of racial minorities in this country.

2. In his personal life, Parks never ceased acting as a humble and yet self-respectful individual, while never succumbing to bitterness even in times when the circumstances called for it.

Being a stoic-minded person, Parks used to address life-challenges as a man, without allowing the hardships he used to experience to prevent him from remaining firmly committed to what he believed was the purpose of his life (Moskowitz 103). Parks felt thoroughly comfortable while socializing with both: Black gangsters, on the one hand, and with the America’s top-politicians, on the other.

This once again suggests that there was nothing incidental about the fact that, despite his humble origins, Parks was able to overcome the seemingly impossible circumstances and to become one of the 20th century’s most influential African-Americans. Therefore, it would be thoroughly appropriate to refer to Parks as a truly inspirational figure, whose cultural legacy will continue to motivate African-Americans make the best out of their lives for generations to come.

3. Parks was a great humanist/intellectual. As it was noted earlier, many of the Parks’ photos are being concerned with promoting the idea that one’s life represents the highest value of all. At the same time, however, Parks never consider joining any of the organized religions in America – hence, proving himself a classical intellectual, capable of understanding that it is specifically people’s lack of education, which prompts them to search for “God” up in the clouds.

Thus, it can be well assumed that, throughout most of his life, Parks remained well ahead of its time. Therefore, it is fully explainable why the overwhelming majority of intellectually advanced Americans tend to refer to Parks in a particularly high regard – regardless of whether they happened to be Black or White.

Thus, it will be fully appropriate, on my part, to conclude this paper by suggesting that, as time goes on, Parks’ cultural legacy will continue to affect the lives of more and more Americans – the very laws of a historical progress establish objective preconditions for this to be the case.

Works Cited

Mitchell, Kristina, Martin-Hamon, Amanda and Elissa Anderson. “A Choice of Weapons: Photographs of Gordon Parks.” Art Education 55.2 (2002): 25-32. Print.

Moskowitz, Milton. “Gordon Parks: A Man for All Seasons.” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education 40.1 (2003): 102-104. Print.