Disease Prevalence

In the United States, hospital-acquired influenza takes one of the first places in children’s morbidity concomitant with the primary disease. The recent study indicates that respiratory viral infections, including influenza, compose an underappreciated cause of the morbidity outbreak in children (Chow & Mermel, 2017). In particular, the retrospective research was conducted at Rhode Island Hospital and Hasbro Children’s Hospital (HCH) and Rhode Island Hospital to compare the prevalence of the given disease in adults and children.

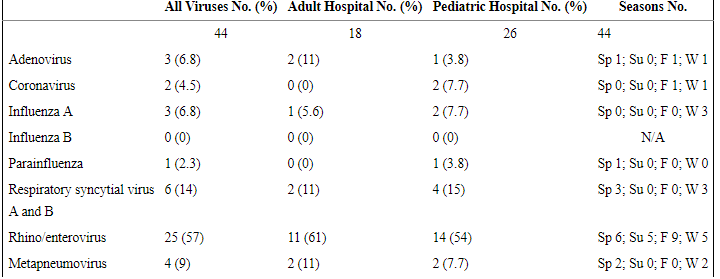

As a result of a one-year study, it was discovered that it was “5 cases/10 000 admissions and 44 cases/10 000 admissions to adult and pediatric hospitals, respectively” (Chow & Mermel, 2017, p. 1). These statistics clearly show that children are at a higher risk of hospital-acquired influenza in the US. The following Table 1 presents detailed information. The strengths of the above data are its direct comparison of different populations and significant sample size, while the limitation refers to covering a small number of hospitals.

The spread of the epidemic of influenza is primarily promoted by a decrease in the immunity of the children of large cities. It is caused by the polluted air of the metropolis and the peculiarities of nutrition, which is not always healthy and full. In some states, more than half of the child population has such problems. Meanwhile, a single integrated approach to the treatment and prevention of hospital-acquired influenza in children in health care has not been developed. This leads to an additional worsening of the epidemic situation in the United States.

Among the negative impacts of the identified health issue, one may note the increased mortality (health consequences), additional costs on children’s treatment (economic impacts), and the threat of pandemics (social aspect).

The chronic medical conditions, as well as early age, facilitate the onset of influenza during the stay at a hospital (Jhung et al., 2014). The study conducted by Jhung et al. (2014) based on Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network (FluSurv-NET) indicated that among 7 million children and 11 million adults, the former are more prone to acquire influenza during their inpatient treatment. The strong point of the mentioned data is coverage of different races and the relevant research method.

The limitation is associated with a limited number of states. The search regarding the comparison of the disease prevalence across the United States revealed no official results. However, it was discovered that patients with low income having limited access to health care services are at a higher risk of morbidity. Nevertheless, the fact that this report focuses on hospital-acquired influenza allows it to be detected at early stages and treated appropriately.

Evidence-Based Intervention

Reviewing the literature presented above, it is safe to assume that timely vaccination against influenza is one of the most effective measures. At this point, it is of great importance to vaccinate not only children but also their families and health care workers, thus minimizing the outbreak of the given infectious disease. As reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2012), immunization is also a cost-efficient solution for such health issues as hospital-acquired influenza in children. The complications of influenza are most dangerous for children’s health. If a patient has a chronic pathology of the cardiovascular system, liver, and kidneys, the influenza virus can cause their exacerbation. A severe complication of influenza is acute pneumonia, which is accompanied by pulmonary edema.

The spread of the influenza virus occurs by airborne droplets, and even short-term contact with a person who is sick may lead to illness. It should be emphasized that it is impossible to exclude all possible contacts. However, one can protect children by creating a protective antibody titer against the influenza virus with the help of vaccination (Osterholm, Kelley, Sommer, & Belongia, 2012).

Vaccination should be carried out well in advance of the epidemic since maximum protection against the virus only occurs two weeks after the introduction of the vaccine (“Influenza vaccination information,” 2017). Therefore, it is better to initiate preventative measures in advance. Vaccination is necessary every year as the immunity from a particular strain of influenza virus is not life-long and persists only during an epidemic season.

The optimal time for vaccination against influenza is the period from September to December. If for some reason, one did not have time to do this, he or she can vaccinate throughout the epidemic period. The antigenic composition of vaccines is updated annually in accordance with the recommendations of the World Health Organization (WHO) since new influenza viruses differ in properties from the previous year (Flannery et al., 2015).

The protective titer of antibodies after vaccination is reduced throughout the year, thus requiring annual vaccination that considerably reduces the risk of infection with influenza in children, and most often, the disease does not occur. In immunocompromised individuals, antibody titers may not be sufficient for complete protection, but even in case of illness, it would be mild and without complications. Along with children, health care workers should also be vaccinated timely. Further research is required to deepen knowledge of hospital-acquired influenza in children regarding barriers and facilitators of vaccination and the subsequent advantages and disadvantages to be revealed in the course of both qualitative and quantitative studies.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2012). Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)–United States, 2012-13 influenza season. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 61(32), 613-618.

Chow, E. J., & Mermel, L. A. (2017). Hospital-acquired respiratory viral infections: Incidence, morbidity, and mortality in pediatric and adult patients. Open Forum Infectious Diseases, 4(1), 1-5.

Flannery, B., Clippard, J., Zimmerman, R. K., Nowalk, M. P., Jackson, M. L., Jackson, L. A.,… Gaglani, M. (2015). Early estimates of seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness-United States, January 2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 64(1), 10-15.

Influenza vaccination information for health care workers. (2017). Web.

Jhung, M. A., D’mello, T., Pérez, A., Aragon, D., Bennett, N. M., Cooper, T.,… Lynfield, R. (2014). Hospital-onset influenza hospitalizations—United States, 2010-2011. American Journal of Infection Control, 42(1), 7-11.

Osterholm, M. T., Kelley, N. S., Sommer, A., & Belongia, E. A. (2012). Efficacy and effectiveness of influenza vaccines: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 12(1), 36-44.