Background

In recent years, one of the recurring debates in the business field concerns the critical role played by marketing strategies in enabling business entities to accomplish their set objectives, including maintaining competitive advantage in the market place (Scramm-Klein et al, 2008).

A rapidly shifting economic environment epitomized by such phenomena as turbulences in the macroeconomic environment, globalization and deregulation of markets, shifting customer and shareholder demands and expectations, and escalating product-market competition, has turned out to be the norm, necessitating organizations to reformulate and restructure their strategies and policies to remain relevant (Topolosky, 2000).

The stakes are even higher in the fashion industry, which has grown phenomenally during the last decade though it continues to be affected by a multiplicity of events, in part, due to the speedy change witnessed in the industry (Tsan-Ming et al, 2010).

One of the fundamental priority areas that have been targeted by companies in the fashion industry as a matter of urgency is the creation of brand awareness among customers and the reinforcement of customer loyalty to boost sales (Bhardwaj et al., 2010).

As demonstrated by Rogerson (2006) and Power & Hauge (2008), knowledge about brand awareness and customer loyalty in the fashion industry is in the public domain, but little is known about how the two important variables can be used effectively to stimulate customer involvement.

Through a critical evaluation of Zara’s fashion retailer marketing strategies, the proposed study will therefore focus attention to providing a framework which can be used to boost sales and improve performance by linking brand awareness and customer loyalty to customer involvement.

With an estimated 1,500 fashion retail outlets in 68 countries and € 6.26 billion in 2007 annual sales, Zara is not only one of the leading fashion retailers globally, but it has also become one of the most widely respected apparel brands worldwide, in part, due to its impressive growth in recent years (Caro et al., 2010).

According to the authors, “…this success is widely attributed to its fast-fashion business model, which involves frequent in-season assortment changes and ever-trendy items offered in appealing environments and at competitive prices” (p. 71).

To support this customer-value proposition, Zara has designed an inventive and highly responsive infrastructure that places brand awareness and customer loyalty at the heart of the whole equation (Scramm-Klein et al, 2008).

Zara’s innovative business model, according to Caro et al (2010) is to a large extent powered by a framework that ensures continuous flow of market information and customer expectations from the retail stores directly to designers. Market information usually incorporates concepts of brand awareness and customer loyalty, and Zara has done extremely well in both.

However, the proposed study makes an assumption that Zara can be able to penetrate virgin markets if it links its brand awareness and customer loyalty strategies to clothing involvement. Hill et al (2010) observes that consumers become more venturesome and willing to buy new brands if their involvement is triggered.

Academic Context

Brand awareness and comprehension about the self have achieved immeasurable significance among consumers in the fashion industry. According to Khare & Rakesh (2010), “…clothing is one domain that is supposed to fulfil both functional and symbolic needs of consumers” (p. 209).

It does not therefore come as a surprise that the emerging perception about the self and the role of brands in boosting the consumer’s image and personality have continued to spur interest among fashion marketers and researchers of modern times.

What’s more, liberalization of markets and globalization have introduced a whole new range of possibilities in the fashion industry, and consumers are now more interested in brands which denote status symbol, superior quality of life and enhancement of self-identity (Rogerson, 2006; Irvin & Montes, 2009).

The youth, in particular, are believed to be a major consumer segment interested in brand awareness and global fashion trends, and are therefore the focus of much attention from marketers in the fashion industry (Power & Hauge, 2008).

Brand loyalty, which implies some form of affective commitment towards a product, has also received broad coverage by academics and marketing practitioners (Tsan-Ming et al., 2010), and available marketing literature demonstrates that brand loyalty is of strategic significance for organizations to achieve and maintain a sustainable competitive advantage (Scramm-Klein et al, 2008).

According to Tsan-Ming et al (2010), brand loyalty in the fashion industry is a multistage process involving “…image-oriented loyalty, marketing-oriented loyalty and then sales-oriented loyalty” (p. 474).

This assertion implies that fashion retailers need to commit more energy to creating an all inclusive strategy that takes onboard customer image concerns, their own marketing paradigms as well as sales strategies to effectively gain brand loyalty.

On its part, customer involvement is a “…state of motivation, arousal of interest, evoked by a particular stimulus or situation, displaying drive properties (Khare & Rakesh, 2010 p. 210). Involvement is largely perceived as an internal state of behaviour, and may either be situational or response-based.

As such, consumers’ involvement with a product generally implies their identification with the product and how internal drives and motivations of such consumers influence their purchasing decisions (Khare & Rakesh, 2010).

The proposed study will extensively borrow from the decision theory, the two-dimensional concept of brand loyalty, and the customer involvement theory to critically evaluate how brand awareness and customer loyalty can be used to stimulate consumer involvement.

The decision theory postulates that in making purchasing decisions, customers give serious attention to a small set of brands which they are aware of and are unlikely to spend much effort in asking for information on unfamiliar brands (Macdonald & Sharp, 2003 p 1).

The two-dimensional concept of brand loyalty, on its part, insinuates that loyalty should be assessed using the customer’s behavioural criteria as well as his attitudinal criteria (Kuusik, 2007). Further, the customer involvement theory deals with issues of how much time, money, initiatives and other resources a customer attempts to employ before making purchasing decisions (Rogerson, 2006).

Consecutive studies as demonstrated by Tsan-Ming et al (2010) and Yuen et al (2010) have shown that fashion consumers are more likely to continue the relationship between brands and themselves if organizations strive to build more solid brand loyalty and brand awareness frameworks.

But while these studies have attracted multidisciplinary responses from industry players, information on how brand awareness and customer loyalty could be used to stimulate customer involvement remains scanty and outdated. More importantly, few studies have assessed the effectiveness of linking brand awareness and customer loyalty to consumer involvement.

Based on this, sentinel surveillance statistics alone are not adequate to guide informed strategy decisions in the fashion retailing industry. Proper understanding of how brand awareness and customer loyalty can be used to stimulate consumer involvement is indispensable if companies are to maintain a profitable margin in the ever-changing and ever-demanding fashion industry. It is this gap that the proposed study will seek to fill.

Methods

The proposed study will employ both quantitative and qualitative research designs to critically evaluate how Zara’s brand awareness and customer loyalty campaigns can be effectively used to stimulate consumer involvement.

Hopkins (2000) observes that most quantitative studies are concerned with evaluating the association between independent and dependent variables, and are either descriptive or experimental. In this perspective, a quantitative research design will serve the interests of this study by evaluating the relationship between brand awareness and customer loyalty on one hand and consumer involvement on the other.

The proposed study will be descriptive in nature because participants will only be measured once (Sekaran, 2006). A survey approach will be used to gather primary quantitative data among selected Zara’s customers to evaluate their perceptions on involvement.

Sekaran (2006) postulate that a survey approach in the form of a self-administered questionnaire is especially effective when the researcher is essentially interested in descriptive assessment of phenomena as is the case in the proposed study.

Primary qualitative data will be gathered by means of key informant interviews, and will target selected marketing executives working for Zara’s Oxford retail outlet, including the marketing manager.

According to Belk (2006), qualitative research designs are predominantly ideal when the researcher is interested in assessing human behaviour, values, attitudes, preferences and perceptions, not mentioning that the designs are mostly used to generate leads, notions, and concepts which can then be used to answer key research questions.

The qualitative approach will therefore be used to evaluate concepts of brand awareness and customer loyalty as well as the practices that the fashion retailer has put in place to enhance the variables.

Secondary data will be gathered by means of undertaking a critical review of literature on the underlying concepts and theories.

The data gathered will then be used to compare the research findings with other previous studies with a view to coming up with probable alternatives and recommendations that could be used to form a value-added linkage between the concepts of brand awareness, customer loyalty and customer involvement.

According to Patzer (1995), secondary data does not only avail to the researcher a pre-established degree of validity and reliability to the issues in question, but it also provides a baseline with which the gathered primary data can be objectively compared to.

The population for the proposed study will comprise marketing personnel and customers of Zara’s fashion retail outlet, Oxford branch. The sample will comprise 10 marketing executives and 150 consumers. The marketing managers will be sampled using purposive sampling technique while consumers will be sampled using convenience sampling technique.

Sekaran (2006) postulates that subjects in a purposive sample are selected based on their deeper comprehension of the variables under study (in this case, brand loyalty, customer loyalty and customer involvement), while a convenient sample includes subjects in the research framework by virtue of being in the right position or environment at the right time.

Quantitative data will be collected from the field using self-administered questionnaires while qualitative data will be collected using key informant interviews. Questionnaires, according to Sekaran (2006), are cost effective and can be administered with much ease, not mentioning that they are effective when the researcher wants to collect confidential data from study participants.

As observed by Cresswell (2005) and Stevens (2003), key informant interviews not only allow the researcher to create rapport with the subjects, hence achieving their cooperation, but they afford the researcher an opportunity to explore and probe further for more information.

Research Ethics

Ethics, according to Stanley et al (1996), refers to the suitability of the researcher’s actions as he go about interacting with individuals who either become the subject of his work or are affected by it.

In addition to requesting for a written permission from Zara’s (Oxford) corporate affairs department and the marketing department to be able to interview the relevant subjects within the premises, the researcher will also take time to explain to the subjects the nature and purpose of the study and read to them their rights, especially the right to informed consent, right to disengage from the research process at their own free will, right to withhold confidential information, and the right to privacy.

The proposed study will not employ deception techniques or offer any financial inducements since the information given is expected to be voluntary. In equal measure, the study will not subject participants to any psychological stress.

Time Scale & Resources

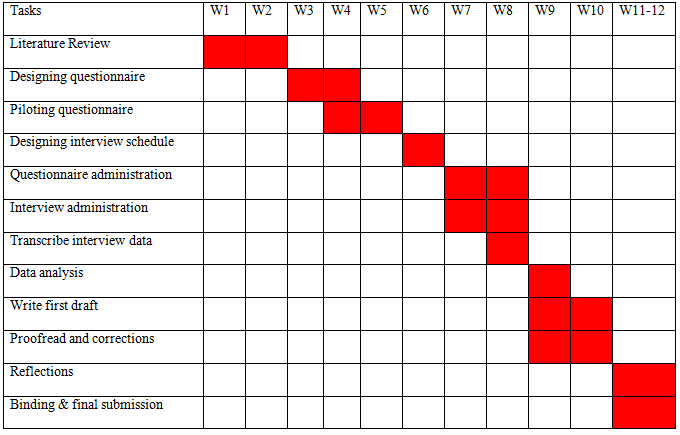

The time-scale for the proposed study (figure 1) is presented in the form of a Gantt’s Chart, which will undoubtedly assist the researcher to visualize the progress of each phase (Thomsett, 2009). The proposed study will take three months to complete – from June 15 2011 through to September 20 2011.

The feasibility of each component has been duly considered and conclusions drawn that the allocated time for each component will be enough to move the study forward.

Academic resources intended to complete the review of literature will be sourced from scholarly databases, including Academic Search Premier, MasterFILE Premier, and Business Source Premier, among others. Time as a resource will be critical for the successful completion of the project. Financial resources to cater for the printing of the questionnaires, travel and accommodation will also be required.

Figure 1: Time-Scale for Proposed Research Study

List of References

Belk, R.W (2006). Handbook of Qualitative Research Methods in Marketing. London: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Bhardwaj, V., & Fairhurst, A (2010). Fast Fashion: Response to Changes in the Fashion Industry. International Review of Retail, Distribution & Consumer Research, Vol. 20, Issue 1, pp 165-173.

Caro, F., Gallien, J., Diaz, M., Garcia, J., Corredoira, J.M., Montes, M…Correa, J (2010). Zara uses Operational Research to reengineer its Global Distribution Process. Interfaces, Vol. 40, Issue 1, pp 71-84.

Cresswell, J.W (2002). Research Design, Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approaches, 2nd Ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Hill, N., Roche, G., & Allen, R (2007). Customer Satisfaction: The Customer Satisfaction through the Customer Eyes. London: Cogent Publishing.

Hine, T., & Bruce, M (2007). Fashion Marketing: Contemporary Issues. London: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Hopkins, W.G (2000). Quantitative Research Design. Viewed <http://www.sportsci.org/jour/0001/wghdesign.html>

Irvin, P.G., & Montes, S.D (2009). Met Expectations: the Effect of Expected and Delivered Inducements on Customer Satisfaction. Journal of Occupational & Organizational Psychology, Vol. 82, Issue 2, pp 431-451.

Khare, A., & Rakesh, S (2010). Predictors of Fashion Clothing Involvement among Indian Youth. Journal of Targeting, Measurement & Analysis for Marketing, Vol. 18, Issue 3/4, pp 209-220.

Kuusik, A (2007). Affecting Customer Loyalty: Do Different Factors have Various Influences in Different Loyalty Levels? Web.

Macdonald, E., & Sharp, B (2003). Management Perceptions of the Importance of Brand Awareness as indication of Advertising Effectiveness. Marketing Bulletin, Vol. 14, Issue 2, pp 1-11.

Patzer, G.L (1995). Using Secondary Data in Marketing Research: United States and Worldwide. Westport, CT. Quorum Books.

Power, D., & Hauge, A (2008). No Man’s Brand – Brands, Institutions, and Fashion. Growth & Change, Vol. 39, Issue 1, pp. 123-143.

Scramm-Klein, H., Morschett, D., & Swoboda, B (2008). Verticalization: The Impact of Channel Strategy on Product Brand Loyalty and the Role of Involvement in the Fashion Industry. Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 35, Issue 1, pp 289-297.

Sekaran, U (2006). Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach. Bombay: Wiley-India.

Stanley, B., & Sieber, J.E., & Nelton, G.B (1996). Research Ethics: A Psychological Approach. New York, NY. University of Nebraska Press.

Stevens, M (2003). Selected Qualitative Methods. In: M.M. Stevens (eds) Interactive Textbook on Clinical Symptoms Research. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Thomsett, M.C (2009). The Little Black Book of Project Management. New York, N.Y. AMACOM.

Tokatli, N (2008). Global Sourcing: Insights from the Global Clothing Industry – The Case of Zara, a Fast Fashion Retailer. Journal of Economic Geography, Vol. 8, Issue 1, pp 21-38.

Topolosky, P.S (2000). Linking Employee Satisfaction to Business Results. New York, NY: Garland Publishing Inc.

Tsan-Ming, C., Na, L., Shuk-Ching, L., Mak, J., & Yeuk-Ting, T (2010). Fast Fashion Brand Extensions: An Empirical Study of Consumer Preferences. Journal of Brand Management, Vol. 17, Issue 7, pp 472-487.

Yuen, E.F.T., & Chan, S.S. L (2010). The Effect of Retail Service Quality and Product Quality on Customer Loyalty. Journal of Database Marketing & Customer Satisfaction Strategy Management, Vol. 17, Issue 3/4, pp 222-240.