Source and Background of the problem

The occurrence of hurricane Katrina came one year after the Department of Homeland Defense (DHS) had already created an emergency response plan following a series of national disasters that had caused havoc in United States. For instance, one unfortunate incidence that left the country in a state of desperation was the September 11, 2001 terrorist attack on the twin towers, the Pentagon building and the World Trade Center.

In fact, the creation of the National Response plan was aimed at setting the right platform for dealing with emergency disasters in future, whether artificial or natural catastrophes. Nonetheless, the response level of hurricane Katrina was deemed as a big failure as documented in myriad of Congressional reports released later.

For example, a report by the House Select Committee in 2006 summarized the response to the hurricane as having lacked initiative right from the state to federal government level. Hurricane Katrina is one of the worst natural disasters ever witnessed in the history of United States owing to heavy loss in life and property.

A White House report on the response to the hurricane pointed a blaming finger on all levels of the government since there was lack of coordination. Another report by the Senate noted that the victims suffered for a longer period than necessary due to delay. The report confirmed that “these failures were not just conspicuous; they were pervasive” (Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Government Affairs, 2006).

Similar to all the prior natural calamities that have ever struck US, early warning signs were released as part of the initial plans to tackle the natural disaster. Unfortunately, the warnings were not heeded by government officials. These officials failed to take sufficient action on the forthcoming disaster.

In addition, Levees had already been built in New Orleans as part of protecting the area against such disasters. However, these structures were not strong enough to wither the strong storm. Moreover, the government had already put in place critical elements of the National Response Plan although the execution of the very elements delayed.

On the other hand, the military are usually ready to deal with natural disasters by assisting in the evacuation process. Further, there were voluntary agencies as well as non-governmental organisations that offered invaluable help in responding to the disaster and recovery process (Brunsma, Overfelt & Picou, 2007).

Disaster preparedness is usually the initial step towards planning for a calamity. Before the onset of the hurricane, there was an emergency response plan readily in place. Nonetheless, it later became evident that the key players in disaster management such as administrators and politicians were not acquainted with the plan. Although standard operating procedures are critical for alleviating confusion when responding to emergencies, this element was the origin of a “red tape” during Hurricane Katrina.

The Federal government played its role of coordinating resources that would be needed by both the local and state governments. These localized coordination structures were further given a facelift by the National Incident Management System as well as the National Response Plan.

Nonetheless, the demanding needs of Hurricane Katrina surpassed the level of preparation of these two agencies. In addition, the resources availed by the Federal government were not adequate (Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Government Affairs, 2006).

This was aggravated by the dysfunctional state of the local government. in the same vein, poor understanding of the drafted plan led to disorderly response whereby resources at all levels namely the Federal, State and local were poorly marshaled. Lack of understanding also interfered with command and control during the recovery process.

It is obvious that there was poor command of the catastrophic event due to breakdown both in communication and coordination (Grant, Miki & Brooke, 2005). The officials at the Federal level made several unsuccessful attempts to bridge the gap by undertaking the roles supposed to be performed by both the state and local officials. Unfortunately, they could not match the increasing needs of the storm; leading to a long, strenuous and failed response to the disaster (Moynihan, 2007).

The activities of voluntary organisations, Nongovernmental Organisations and other key players should be coordinated well in advance in order to effectively handle disasters in future.

For instance, the duplication of response and recovery activities by the various recovery teams was cited as a major failure in New Orleans area. Another suggested way of improving response plan in future disasters is through the implementation of the after action reports especially on those pointing out on who is responsible at the federal level going down whenever such disasters strike.

This essay takes a theoretical policy analysis of hurricane Katrina and how the Incident Command System (ICS) was used or should have been used in responding to the disaster. In addition, recommendations and modifications that should be put in place as part of disaster preparedness and management are discussed at length.

The policy problem

The problem tackled in this policy paper is how best the Incident Command System (ICS) can be employed when responding to either anthropogenic or natural calamities in order to minimize loss in life and destruction of property.

The manner in which government agencies and responders conduct emergency coordination during disasters has been a major concern in the recent past, especially when hurricane Katrina struck the New Orleans area. Nonetheless, the fact that a swell organized and standard system is needed during incidents of catastrophes has been in place for quite a number of decades (Oliver, 2011).

Tracing back the California fires in 1970, a similar hitch in terms of preparation by emergency responders was also witnessed. Although the incidence was multijurisdictional, it could have been brought under control with adequate preparation.

The task of coordinating various rescue teams and departments was enormous (Brunsma, Overfelt & Picou, 2007). Later, the agencies confirmed that it was a smooth ride in coordinating response teams responding to fires owing to miscommunication and rampant mix up. Eventually, a total of 16 people lost their lives in addition to destruction of about 700 structures.

This is just one example of past incidences where response teams failed to prepare themselves well in advance amid the oncoming disaster. It was after this fire incident that ICS was established as a command unit to prepare, plan and manage disasters inflicting the country. For a long period of time now, ICS has been incorporated in several rescue missions across United States ranging from oil spills to terror attacks.

Moreover, the ICS has been found to be beneficial in four main areas. Firstly, it facilitates better focus for rescue teams on the ground. The unit is run as a hierarchical structure with set objectives within a limited period of time depending on the emergency issue at hand. Secondly, it enhances effective resolution of the incidence since the situation at hand is assessed from a broad base and narrowed down to a small focus so that it can be resolved within the shortest time possible.

Third, it promotes incident organisation and finally, ICS tends to attain an expedited resolution to the incidence. In any case, proper incident management during disasters can assist in resolving broader issues and is particularly helpful for any affected community. They also felt that incident management plans could resolve broader issues and would be better for the community.

Hurricane Katrina could have been dealt with decisively by government agencies and other emergency responders if the incorporation of ICS into the calamity was effected to the letter (Brunsma, Overfelt & Picou, 2007). Through ICS, the key stakeholders such as the army, Department of Homeland Security, FEMA among others would have been brought into a common platform instead of each of them wasting away their efforts separately.

Utilities that do not make use of ICS may experience hardship when they are handling an emergency occurrence in form of a disaster. In the case of hurricane Katrina, the responders were largely reported to be unprepared. However, the missing link was likely to be isolated rescue efforts which affected their effectiveness and efficiency standard in the course of operations.

Perhaps, it is imperative to note that the overall responsibility of the Incident Commander (IC) is primarily to manage the on-scene emergency occurrence as the leader of the ICS structure. The role of the IC is particularly notable on major incidents like was the case with hurricane Katrina. It is against this backdrop that the magnitude of the hurricane Katrina should have been accessed thoroughly so that the IC could assume his role to the letter as the head of the organisation.

Unfortunately, the structure and working principle of ICS has largely been ignored or misunderstood. Though it is just one unit, it has a blend of several unrelated agencies whose functions have to be well coordinated if their efforts is to bear any fruits. Emergency incidences that are small in size can be managed or headed by the most senior official heading the rescue crew and may fully assume the role of the Incident Commander(Alan, 2005).

Hurricane Katrina was reportedly growing in size from a tiny storm to a widespread tropical depression hurricane. A few days after the onset of the storm, it seemingly grew and consequently, the Mississippi and Louisiana Governors decided to declare state of emergency in the affected areas. In addition, the predictions of the National Weather Forecast were as dynamic as the storm was progressing. At some point, the weatherman predicted that catastrophic flooding follow soon.

At this point, the application of ICS should have come in handy. As an emergency incidence grows in severity and becomes more complex, more competent crew should be directed in the worst affected areas. It is common knowledge that an incidence big in size definitely require rescue officials who are more qualified. It is also at this juncture when the IC may be replaced with a more skilled and experienced personnel. It is more likely that this did not materialize during hurricane Katrina.

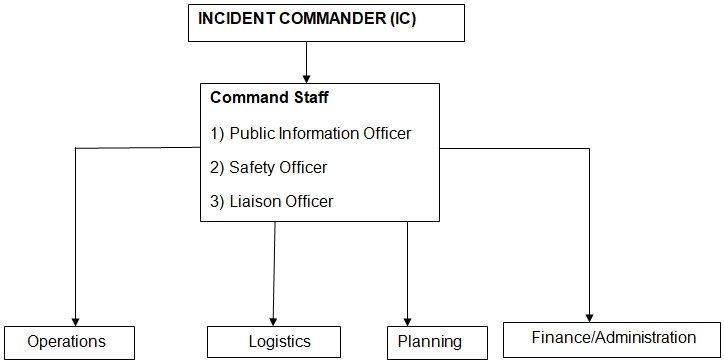

Incidents that are larger in magnitude and require restoration efforts that may take considerably long, the Incident Commander ought to establish various operating sub-units all within ICS. These units include finance and administration, planning, logistics and operations. Besides, a command staff, liaison personnel as well as information safety sub units are paramount.

It is interesting to note that all these support sub-units were established by the IC but lack of coordination and late response on the disaster acted as major setbacks to the rescue process. Let us now have a critical look at each of the five organizational tools within ICS that were employed and how they could be improved.

Management

A significant section of the Gulf Coast was devastated by hurricane Katrina. In addition, the natural landscape around Texas, Louisiana and Mississippi were equally ruined by the storm.

The Department of Homeland Security located in Louisiana in conjunction with the Emergency Preparedness team camped at the state level to execute the rescue efforts (Brunsma, Overfelt & Picou, 2007). Still under management, the emergency office located in New Orleans assumed the role of giving orders regarding evacuations as well as obtaining information on the progress of the storm.

In addition, the office acted as the centre through which life safety could be provided after the needs of the victims had been identified. Both the Department of Homeland Security and Emergency and the City of New Orleans rescuers worked hand in hand in spite of poor coordination. Another wing that assisted with voluntary evacuation was the Federal Emergency. The state of Louisiana and the Gulf Coast area were catered for by the combined efforts of these agencies.

This management plan sounded good although there were numerous pitfalls before and during its execution (Grant, Miki & Brooke, 2005). The top management of ICS which includes the Incident Commander, Liaison Officer, Public Information officer as well as the safety officer is supposed to sit on a round table and then draw a common plan for managing the disaster (Alan, 2005). It is evident that each of these officials was more or less working as an individual.

For instance, it is reported that evacuation orders from the worst hit areas came too late from the Governor of New Orleans, not even among the lead agencies such as the Department of Homeland Security on Emergency Preparedness and Planning. Moreover, the safety officer is also expected to work directly under the information officer so that the necessary safety action is taken based on the progress of the calamity. It is most likely that this was not the case.

Operations

The nearby parishes as well as the fire department derived from New Orleans were part of the emergency operations at the site of the hurricane. There were also other numerous agencies such as the Emergency Medical Services and the ambulance services that offered medical help and first aid services to the affected victims. Several other regions such as California, Texas and Missouri were served with ambulances. In order to keep law and order, the New Orleans Police Department was on the fore front.

Other law enforcement agencies that were involved in the safety operations included Louisiana Fish and Wildlife and the State Highway Patrol. Direct government agencies include FBI, Tobacco and Firearms and the Federal Emergency Management Agency among several others. The American Red Cross and the United Methodist Emergency Response provided the support services. Others in this category were the Salvation Army and other volunteer agencies such as the Southern Baptist Convention.

As can be noted, this was a relatively huge team all working under the unit of operations. For the effective application of ICS in managing disasters, and especially when there are myriad of aid agencies working under the same unit, it is necessary to allocate each agency a specific role to play in order to avoid duplication of duties.

This is likely to have happened during hurricane Katrina. Under the operations unit of the ICS, there are still other branches that should be linked up during rescue operations in order to facilitate the optimum rescue and recovery process. Under the branches, there are divisions and groups whose functions have to be identified so that they do not engage in rescue process which is either below or above their capacity. Further below the divisions are the strike teams, the task force as well as a smaller unit that manages a single resource.

The agencies that were assisting the rescue process carried their duty at random without any due consideration of their specific responsibilities. Furthermore, the top ICS leadership namely the Incident Commander, public information officer, safety officer and the liaison officer failed to coordinate the various government and volunteering agencies, leading to delay of recovery process occasioned by either undertaking the same roles or taking too long to respond as a result of poor liaison.

Planning and Intelligence

This falls under the planning section. As was expected, all information regarding the progress of hurricane Katrina was being received by government personnel situated at all levels. The report released by the National Weather Service was used by the government as decision point on what type of action was necessary within their respective geographical location (Walker, 2006).

On the part of the National Weather Service (NWS), warning signs was issues well in advance and even in situations where evacuations were necessary, NWS did its best to deliver information. The evacuation notices given to victims emanated from the NWS via the local and state governments (Cherry, 2009).

This led to a very short time for people to vacate the identified hot spot areas. Consequently, some victims ended up being trapped by the storm as buildings and structures collapsed. Moreover, the Louisiana government, both at the local and state level only relied on voluntary evacuation posing more danger to civilians who were oblivious of the hanging danger. Hence, most of those who lost their lives failed to adhere to the evacuation requests.

For the planning and Intelligence unit to function well in an ICS structure, it is pertinent to understand the functions of the four main sub units under this section. The sub-units are those that deal with resources, demobilization, situation and documentation. Let us consider the resource unit under planning and intelligence (Rodrígue, 2007). It is worth to note that all rescue officials as well as assets used during a rescue mission should be tracked down.

On the other side, resources may also be reimbursed during emergency operations in order to meet the urgent needs. Effective management of resources entails grouping them according to need and their frequency of use, requesting for more supplies of resources being used for rescue and response action, dispatching and tracking down the use of resources as well as making sure that there is a mechanism in place that can be used to recover resources and other assets.

Over and above the aforementioned components of resource management during disasters, it is also a critical part of planning and intelligence to ensure that all the resources needed are visible enough so that they cannot only be identified easily but also dispatched to respective locations where they are needed the most.

Logistics

As already noted, the Gulf Coast region was heavily destroyed by hurricane Katrina. There was decimation of buildings in most parts of Mississippi and neighboring states. For instance, the port situated at Mississippi was almost completely swept away.

The warning issued by the National Weather Service through the local and state governments made it possible to activate some of the resources that would be needed during response time. Although there were adequate transport logistics, the Federal resources were not moved immediately to the hot spot regions since the Louisiana Governor did not request for the same (Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Government Affairs, 2006).

The levees that had been built broke down immediately the storm hit Louisiana. Again, ICS failed to make any tangible move at this initial stage. As a result, several response agencies embarked on evacuation and rescue efforts. This was done at random and without any coordinated approach leading to further loss. The numerous response units such as the US Coast Guard and FEMA dispatched by the Federal government came delayed as it was too much but too late and was largely an exercise in futility (Moynihan, 2007).

The logistics section in ICS functionality is even much more complex compared to other areas of operations. It has four sub-units and two main branches that all required to be coordinated during emergency response. The service branch works hand in hand with the support branch in making sure that the four units namely communication, supply, and medical and facilities deiver on their respective roles.

Finance and Administration

A Presidential Disaster Declaration was announced due to the magnitude of hurricane Katrina. The main rationale behind this declaration was to assist in expediting the process of funding or financing the catastrophe.

Indeed, FEMA was able to take care of several costs associated with rescue and recovery of victims. Although funding request to the top authority in the land is usually not a common phenomenon, lack of casinos in the City of New Orleans led to the request for additional funding. Unfortunately there were no casinos in the city before the disaster struck.

Four main units are instrumental in financing and administration under ICS arrangement. These are time, cost, procurement and compensation claims units. Unless each of the individual units is coordinated with each other in terms of activities, the rescue process will be disarray.

ICS engagement is required at incidents of all magnitudes. Initially, the system was operated under the NIMS model. However, the changing times coupled with varying trends of calamities necessitated the need to transform the NIMS protocol to ICS. As a result, there are additional structures in the new system. This is the reason why finance and administration has four different units so that each unit can be assigned its roles and responsibilities during disasters (Cherry, 2009).

Policy Alternatives

In order to address viable solutions in the management of disasters similar to hurricane Katrina, four policy alternatives have been analyzed in this paper.

Early warnings and positive response

Hurricane Katrina did not occur unexpectedly. The National Weather Service provided sufficient warning well in advance. However, inadequate preparation characterized the disaster leading to last minute rush and uncoordinated, random rescue and evacuation efforts (White House, 2006). Of particular interest was the City of New Orleans. The weatherman had provided early warnings and the impacts of the storm were long awaited.

FEMA took almost half a decade to seek funding in preparation for the hurricane. Therefore, there is no higher duty in ICS than responding positively to early warning signs. Indeed, this was the major setback in addressing hurricane Katrina. The high number of casualties would not have been realized if decisive steps were taken after it was evident that hurricane Katrina would wreck havoc in the foreseeable future.

Comprehending complex systems

The delay characterized by the response action of several aid agencies was largely as a result of poor understanding of the complicated ICS structure. It is vital to note there are only a handful of top trained personnel manning ICS. Most of the aid agencies comprises of voluntary officers who may not necessarily be highly competent in rescue and recovery plans during disasters of high magnitude.

Hence, as a policy alternative, the Federal government should embark on a mandatory training program for all officials working under the ICS umbrella. This will assist the personnel in comprehending the complicated ICS functions and emergency response skills.

Handling dispersed responsibilities

Quite often, the US Federal government has a tradition of engaging in disaster management long after the local and state governments have been overwhelmed. However, this “pull” tactic usually comes late when capacity at the local level has grossly been overwhelmed and possibly devastated.

The Federal responders took a lot of time before they could respond to urgent needs of the disaster. Hence, there is conspicuous lack of “push” approach when responding to disasters. The emergency responders should act immediately on disaster management rather than endure a long wait from the higher authority (White House, 2006).

Organizational capacity

It was quite cumbersome for responders to curtail the devastating effects of hurricane Katrina due to its overwhelming magnitude of the calamity. One theory has it that there is urgent need to expand institutional and organizational capacity of individual aid agencies so that they can adequately handle disaster of any size (Alan, 2005).

Capacity challenges made the response process less efficient. It is also evident that FEMA lacks the institutional capacity to deal with large scale catastrophes. Policy alternative by expanding organizational capacity is the most applicable way to go.

Policy Recommendations

There notable policy recommendations that have been put proposed in this paper as part and parcel of revamping the working of Incident Command System (ICS) during emergency response. Firstly, the level of preparation among the ICS responders should be elevated.

There is need for an ICS structure that is not only ready to tackle disasters of any nature but also that which has a clear hierarchy with emergency responders who are skilled and competent and can work harmoniously as a cohesive team. although it may be close to impossible to meet such a target, it is highly recommended that ICS should demonstrate self initiative towards achieving this ideal.

Moreover, prompt response should be a key operating principle by ICS leadership. This can only be achieved through a vivid chain of command understood by all officials under the ICS umbrella (Grant, Miki & Brooke, 2005).

It is also proposed that the coordination network of voluntary groups who might be willing to offer help during disasters should be reviewed. Past experiences have revealed that such groups which are not part of ICS may be problematic during rescue and recovery missions. Hence, a central coordination point with a toll-free communication line ought to be established so that interested external parties can be assigned roles without causing mayhem and confusion (Davis, 2007).

Network relationships should be made stronger than they are currently. The general perception by other aid agencies is that ICS is one cohesive team and not a collection of several emergency responders. Quite often, ICS takes too long, or even fail completely to create the necessary relationships needed among the various teams. It is vital to note that warm and cordial relationships among the different groups will enhance team spirit towards achieving a common goal (Moynihan, 2007).

Finally, this policy paper suggests that the relative importance of hierarchy within ICS should be adhered to when confronting disasters. The Incident Commander should not just manage the system but above all, take the real leadership role. For instance, there are circumstances which might demand immediate decision and action from IC rather than call for a meeting (Oliver, 2011). Hence, hierarchy and the role played by each unit should clear and definite.

References

Alan D.C. (2005). Hurricane Katrina Represents A Failure to Communicate. Signal,60(4), 61-62.

Brunsma, L.D., Overfelt, D. J. & Picou, S. (2007). The sociology of Katrina: perspectives on a modern catastrophe. Plymouth: Rowman & Littlefield.

Cherry, E.K. (2009). Lifespan Perspectives on Natural Disasters: Coping with Katrina, Rita, and other storms. New York: Springer.

Davis, E.L. (2007). Hurricane Katrina: lessons for army planning and operations. Santa Monica: RAND Corporation.

Grant, D., Miki D. & Brooke D. (2005). The Incident Command system. Electric Perspectives, 30(6), 60-64.

Moynihan, D. P. (2007). From Forest Fires to Hurricane Katrina: Case Studies of Incident Command Systems. Report to the IBM Center for the Business of Government. Web.

Oliver, C. (2011). Catastrophic Disaster Planning and Response. Boca Raton: CRC Press Publishers, Inc.

Rodrígue, H. (2007). Handbook of disaster research New York: Springer.

Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Government Affairs. (2006). Hurricane Katrina: A Nation Still Unprepared. New York: Government Printing Office.

Walker, M.D. (2006). Hurricane Katrina: GAO’s Preliminary Observations Regarding Preparedness, response and recovery. New York: United States Government Accountability Office.

White House (2006). The federal response to Hurricane Katrina: Lessons learned. Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office.

Appendix