Introduction

The Hausa community is one of the largest ethnic groups in Africa. The Hausa are culturally homogenous people, who are predominantly concentrated in the western part of Africa. The Hausa people have also spread in other parts of Africa, such as the Northern region, through trade. They live in isolated settlements, and they practice subsistence farming together with animal keeping and local trading. The Hausa language dominates the other languages in sub-Saharan Africa, with most of them living in Nigeria, Niger, Cameroon, Ivory Coast, Chad, and Sudan. The question of what it entails to be Hausa is briefly addressed to uncover the dynamic nature of Hausa culture and the religion that plays the main role. Despite their ethnic affiliations, the majority of the Hausa people practice the Islamic religion.

The study of the Hausa art offers a rich account of the acculturation of the Islamic people in Africa. The Hausa religious beliefs have contributed to the design of the most renowned walled Islamic Hausa buildings as well as dressing.1 This paper will show that the strong Islamic beliefs shared by the Hausa people have been predominantly rooted in their lifestyle to the extent that it defines the dress code and building designs, among other issues. This interrelationship defines the similarities that are depicted in the Hausa clothing and architecture. The Hausa “indigenous architecture is famed for its ribbed vaulting and doming, which have social implications on the mode of dressing”2. The majority of the Hausa building designs have a direct implication on their lifestyle, relationship with other people, and mode of dressing. This homogeneity is developed and sustained by strong religious beliefs, which are shared by the Hausa people.

Islamic art

Although the Hausa people are not purely Muslims, Islam has played a continuing role to the extent where today, being a Hausa is interchangeably defined as being a Muslim. In the Hausa land, both traditional and innovative elements of Hausa art were considered when determining the dress code and building designs. One aspect that became persistent throughout the workshops was the community’s tradition of religious tolerance and respect, which differentiated religious groups through dress code, architecture, literature, and trade. The Hausa artistic products have been affected by the interplay between art and the influence of Islamic religious beliefs and values. The process of pattern and design exploration takes into account various traditional values cherished by the Islamic religion. For architects, the key objective of artworks was to convey Islamic messages with little or no consideration of aesthetic gratification.3

Hausa Clothing

Clothing was, and it continues to be defined as the material culture, which symbolizes identity. Amongst the Hausa people, cloth has many functions, and for many years it has been used for dressing, trade, and as a symbol of differentiating religious, economic, political, social, and ethnic identity. As an item for use in religious rituals, cloth in the Hausa community continues to uphold the religious beliefs.

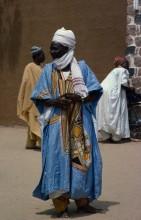

The dressing style amongst the Hausa is confined to set standards based on Islamic tenets and requirements. The symbolic functions of cloth were essential to the Islamic society to the extent of influencing the demand for textiles based on Islamic art. The main form of men “clothing is the big gown, which is referred to as the Babban Riga and it is embroidered with a robe known as jalebi and colorful embroidered caps, which are referred to as Fula; on the other side.4 On the other side, “women were recognized due to their abaya wrappers designed from a colorful cloth, a matching top, and a shawl”.5 Dressing only differed across social classes, but within the same social status, common dressing served as an identity marker.

Such dressing influences were encouraged by the religious values and the powerful classes, which were interested in richly embroidered dresses coupled with decorating their houses with the same design as their gowns. These consistent decorations served as symbols of unity as well as conveying the Islamic religious values portrayed in the calligraphy. Figure 1 below shows the huge flowing gowns embroidered with elaborate features and designs based on Islamic beliefs.

The Hausa architecture

The Hausa architecture, which is commonly referred to as Tubali, is a unique pattern among the various Hausa Islamic believers found throughout Africa with little variations influenced by class, region, and external cultures. The Fulani jihad was the breakthrough in West Africa that offered new nomadic sedentary and religious hegemony. This peculiar set of situations inaugurated the Hausa architecture.

The traditional closed form of buildings was gradually replaced by the new building technology that embraced new architectural meaning and imagery. Unlike the previous forms of architecture, for the first time, the visual imagery portrayed through calligraphy reflected the Islamic tenets of the religion. In most cases, the Hausa buildings were constructed using dry mud bricks, and they were decorated based on Islamic values. Painting is done in vivid colors, which are meant to pass the message about the religion and status of the occupant. With the stringent Islamic injunctions restricting informal interactions between opposite sexes, the Hausa houses were designed in ways that provided the utmost privacy of the people inside the residences.7

The Hausa buildings were enclosed in a compound referred to as zaure, whereby people would freely interact. Apart from providing space for social interaction, the zaure acted as a religious symbolic space. However, being a symbol of Islamic belief, the architectural meaning was given profound attention to ensure that nothing deviated from the Islamic faith right from the foundation to decorations. Similar attention was awarded to the textile industry, which ensured that clothing embraced Islamic religious beliefs. Muslims believed in concealing much of their body, which influenced the textile art to focus on long flowing gowns with messages advancing the Islamic faith.8

With the introduction of the Fulani-Hausa jihad values, the architectural models offered a close expression of the Islamic belief. For instance, the walls of the Sokoto Caliphate assumed the shape of a perfect square, and each side had an entrance. The design of the perfect square was transcribed in the writings by Muhamed Bello, which he adapted from the teachings of the early Muslim conquest, as defined by the ancient authorities.9 The Hausa Vault and Hausa dome were keenly adopted from the Fulani architectural components reflecting the Islamic religious values. Figure 2 below shows an architectural design of the Hausa vault under construction. The rib-like intersection is a symbol of the inherent cohesion and unity advanced in the Islamic religion. The vaults were firmly attached to ensure continuity and longevity, which were reflected in the Muslim faith.

Uthman Dan Fodio

Uthman Dan Fodio was a member of the Fulani community. The Fulani tribe is widespread in Africa, but it is highly concentrated in West Africa. Some members of the Fulani tribe settled alongside the Hausas and assimilated to Hausa culture. The antecedents of Uthman migrated into Hausa land around the 15th Century and settled in the State of Gobir. Uthman was born in 1754 in Gobir and died in 1874 in Sokoto.11 The emergence of Uthman as a great teacher of the Islamic religion proved to have a significant influence on the Hausa culture. The early 18th Century Hausa land was nearing a stalemate, and it needed a swift intervention to recover its conscience.

Open defiance of the Islamic religious teachings and oppression enshrouded the Hausa people. The social system was rapidly turning immoral as men dominated and mistreated women. Allah’s laws were blatantly defied, and everything was redirected to benefit the rulers and the elite. This situation needed a profound challenge from a revolutionist. As a reformist religious teacher, Uthman instructed the Hausa people to abide by proper teachings and practices of Islam. The imparting of the concept of tajdid, which is also referred to as the Revolution, to his followers and engaging them in the process of renovating and tajdid, as a necessary field of practice, was undeniably his fundamental contribution among the Hausa people. Uthman taught that any teaching opposed to the Qur’an was supposed to be rejected. Spiritual teaching and revival of the Islam faith through symbolism was the central tenet of his teachings.

The revolution of Uthman was the turning point and wide-reaching since it brought together the people that led to the organization of the Hausa land into one single entity joined in the search for unity, stability, and love that they had never experienced. New moral and social values emerged, his teachings, mode of dressing, and value for true Islamic values inspired Muslims all over the Hausa land. As much as he taught about the right ways of Prophet Muhammad, Uthman was keen on his way of dressing, as his clothing strictly reflected the Islamic religious values and motivated the people of Hausa to express their faith in Islam through material cultures such as clothing and building.12

In addition, he changed what mainstream society thought about women. The Hausa culture described the role of women as subordinate to men. He devoted to the education of women and empowered them to become independent. In 1804 following the jihad and victory of the Fulani against the various Gobir cavalry at Kwotto, Uthman’s daughter indicated that the Hausa herdsmen, who had previously been mistreated by the ruling elites, would have the pleasure to live in houses and express their religious values.13 This perception embodied both architectural meaning and clothing ideals, which had previously been in vain.

The Fulani-Hausa inspired jihad brought forth Islamic-centered institutions whose major goal was to incorporate the abandoned and desperate Hausa tribe. Even though the focus of the jihad was Islamic reform, the most profound effect of the revolution was the introduction of a prominent culture that embraced religious teachings in all aspects of life. The jihad also transformed the Hausa livelihood from purely pastoral nomadic and peasantry lifestyles to partially sedentary ones. In so doing, the revolution developed a new aesthetic coupled with generating a new set of symbols, art, and new meaning in architectural designs.

Even though Islam and Islamic art had already been established in many parts of Africa before the time of Uthman’s jihad, the previous effects of Islam had minimal influence on the existing cultural milieu. Following the jihad, the new Islam religious teachings inspired the growth of urban architecture and the code of dressing that reflected the religious and cultural values of the Maghreb. With the inherent interlink among the dress code, architecture, and religion, attempts to establish the ideal designs circumvented within the cultural and religious values advanced within true Islam. Mosques, palaces, the compound walls enclosing the azure, and city buildings attempted to resemble the religiously prescribed designs. The arabesque patterns in buildings became a requisite for all architectural designs embedded in all structures perceived as sacred. The same patterns were reflected in clothing.

Arabesque patterns on clothing and architecture

The arabesque is “a type of artistic surface decorations made of linear patterns and interweaving foliage or plain lines, and usually, it is combined with other aspects of art”14. The Islamic art arabesque is an often element in major works of art, and it is highly used in the decoration of clothing and architecture. Arabesque patterns of Islamic art are said to trace their origin from the Islamic view of the world and particularly religion.15 Islam does not depict people or animals, as most Christians do in their art.

Islam views calligraphy as a visible demonstration of the most significant art, viz. the art of the verbal word. Muslims believe that the Quran is the only book of the essence to be passed from a Supreme Being to a human being orally. In contemporary times, the Qur’an message is depicted in arabesque art. With this connection to the Qur’an, Muslims believe that arabesque art is a symbol of their shared faith and that the Islamic people view the world through Islam. In addition, this connection implies that arabesque art developed as early as the time when Islamic religion started to permeate the Hausa land. Figure 3 below displays the arabesque art, which is used to decorate buildings. The arabesque adopts floral patterns showing how the Islamic faith exalts and appreciates Allah’s perfect creation.

Just like in architecture, arabesque patterns are expressed in a similar manner in clothing. Intentional repetitions are done on decorations for both architecture and clothing to symbolize humility and affirm the fact that only Allah is perfect in his doings. The sequential patterns of arabesque art in clothing and architecture portray unity that is shared amongst the Hausa people through material culture. Both used in clothing or architecture, arabesque art served as a tool of inspiration, appreciation of Allah’s nature, and a guide for the Islamic faith.

Conclusion

Islamic art offers an insight into faith and tenets of the Islamic religion and culture across generations. The most striking feature portrayed in Islamic artwork is the outstanding visual evidence of inspiration, reference, and guidance to religious values. The Hausa Muslim society demonstrates unity and uniformity, as portrayed using arabesque art to design buildings and clothing. This similarity and sequential designs portray the actual image of the Hausa people, coupled with how they view and understand Allah’s creation. Although not all signs and symbols used in clothing and architecture reflected religious values, significant perceptiveness should be granted to the Islamic religious art, which laid the foundation for artworks. Apparently, the Hausa art has spread across Africa, and the impact has been the assimilation of other communities into the Hausa culture and beliefs about the Islamic faith. The continuity of the Hausa art symbolizes the sustainability of the Islamic values and its significance to the world.

Bibliography

Adamu, Abdalla. Transglobal Media Flows and African Popular Culture: Revolution and Reaction in Muslim Hausa Popular Culture. Kano: Visually Ethnographic Productions, 2007. Web.

Bature, Abdullahi, and Russell Schuh. Hausar Baka “Gani ya kori ji”: Elementary and intermediate lessons in Hausa language and culture. Windsor: World of Languages, 2008. Web.

Bloom, Jonathan. Arts of the City Victorious: Islamic Art and Architecture in Fatimid North Africa and Egypt. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007. Web.

Clough, Paul. “The Impact of Rural Political Economy on Gender Relations in Islamizing Hausaland, Nigeria.” Africa 79, no. 4 (2009): 595-613. Web.

Dobronravin, Nikolay. “Classical Hausa’ Glosses in a Nineteenth-Century Qur’anic Manuscript: A Case of ‘Translational Reading’ in Sudanic Africa?” Journal of Qur’anic Studies 15, no. 3 (2013): 84-122. Web.

Ghasemzadeh, Behnam, Fathebaghali Atefeh, and Tarvidinassab Ali. Symbols and signs in the Islamic architecture.” European review of artistic studies, 4, no. 3 (2013): 62-78. Web.

Haour, Anne, and Benedetta Rossi. Being and Becoming Hausa Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Leiden: Brill, 2010. Web.

Jibo, Nura. Traditional Hausa Architecture in Northern Nigeria: Design and Building of the Royal Palace, City Walls, and Gates of Northern Nigeria. Saarbrücken: LAP Lambert Academic Publishing, 2011. Web.

Kwasi, George. “Fiddling in West Africa: Touching the Spirit in Fulbe, Hausa, and Dagbamba Cultures.” International Journal of African Historical Studies 41, no. 2 (2008): 362-365. Web.

Walker, Paul. “Arts of the City Victorious: Islamic Art and Architecture in Fatimid North Africa and Egypt.” The Journal of the American Oriental Society, 128, no. 1 (2008): 182-183. Web.