Abstract

This paper provides a critical review of the theories of change and innovation, as well as, leadership of change and innovation. It also presents an assessment of my leadership skills, as well as, examples of change processes that I have participated in.

The change that I successfully led involved improving the website of a bank. This change was successful because of effective planning and my ability to create a sense of urgency. In addition, a team of experts from the bank who had a clear understanding of the company’s needs modified the website.

A less successful change that I have led involved renovating 32 bank branches and increasing the efficiency of serving customers. This change failed because of inability to eliminate obstacle (financial constraints) and early declaration of victory.

An analysis of my leadership skills reveals that am capable of creating urgency for change and the vision to guide its achievement. My main weakness is inability to eliminate obstacles to change.

Introduction

Innovation refers to the creation of new customer value by developing solutions that satisfy emerging needs, unarticulated needs, as well as, existing market needs in a different manner.

Change, on the other hand, involves initiating and managing the consequences of new business processes, organizational structure, and culture. In most organizations, change and innovation often occur simultaneously.

Thus, the two can be conceptualized as two sides of the same coin. Figure 2, in the appendix highlights the increase in innovation in the UK, in terms of expenditure on R&D. Change and innovation can be realized if effective leadership guides the process.

This paper presents a critical review of various innovation and change theories. An assessment of my leadership skills will also be discussed.

Critical Review

Creativity, Innovation and Change

Creativity, innovation, and change are related concepts that managers often use to create competitive advantages for their organizations. In the business world, creativity is associated with the production of novel and valuable products (Imtiaz 2012, 326-332).

Thus, creativity refers to “the mental ability to conceptualize new, unusual, or unique ideas and to identify the new connection between random and unrelated things” (Barcana 2010, pp. 6-7). In this regard, creativity involves the production of an original and worthwhile product.

According to Amabile (1997, pp. 39-58), creativity is determined by the following factors. First, organizational encouragements facilitate creativity. Creativity develops in an environment that supports risk-taking.

Additionally, motivation facilitates creativity by influencing the extent of explorations, as well as, the possibility that alternative responses will be evaluated. Intrinsic motivation develops within an employee because of the interest, satisfaction, and challenges that are associated with the execution of a task.

A performance-based reward system often leads to the development of intrinsic motivation. Second, resource availability determines the level of creativity in an organization. According to Amabile (1997, pp. 39-58) the resources that facilitate creativity include sufficient funds, training programs, and work materials.

Finally, creativity develops in organizations whose management practices encourage autonomy among the employees.

Innovation is the process in which the ideas generated through creativity are transformed into actual products or processes. Thus, creativity leads to innovation. According to Von and Stamm (2009, pp. 49-66), innovation does not only require the use of structured processes, but also changing the behaviors of people.

Moreover, significant innovation can only occur if several processes are used to achieve it. In this regard, innovation brings about change in the organization. Organizational change involves executing business activities through new and better processes that facilitate value addition and efficiency.

Organizational change also involves transforming norms, values, and business cultures. This helps managers to align their organizational culture to the desired change (Bent, Paauwe & Williams 1999, pp. 377-404). The foregoing discussion indicates that creativity, innovation, and change are interrelated concpets. Thus, an organization that intends to achieve meaningful change must encourage both creativity and innovation.

Innovation

According to Tidd & Bessant (2009, pp. 3-50), innovation refers to successful utilization of novel ideas. This involves the use of new or improved ideas to perform technical, manufacturing, and management activities that are associated with the production of a new or an improved product.

Goffin & Mitchell (2010, pp. 1-40) assert that innovation is characterized with technological improvements and the use of better techniques to perform business activities. They further, state that innovation is manifested in processes such as product development, and strategy formulation among others.

In this regard, innovation refers to “scientific, technical, commercial, and financial steps that are necessary for the successful development and marketing of new or improved products” (Goffin & Mitchell 2010, pp. 1-40).

Furthermore, innovation includes the development of new or improved business processes. Based on these definitions, the fundamental elements of innovation include change, the degree of change, as well as, the source of the change and its influence. These elements define the different types of innovations.

Types of Innovation

Goffin & Mitchell (2010, pp. 1-40) categorize the various forms of innovation according to what is being changed and the degree of the change. With reference to the thing that is to be changed, Goffin & Mitchell (2010, pp. 1-40) identify three types of innovations namely, process innovation, services innovation and product innovation.

Service innovation involves creating new services or improving existing ones in order to satisfy market needs. Similarly, product innovation entails the development of new products or improving existing ones in order to meet the customers’ expectations.

In process innovation, organizations develop new business processes or improve existing ones in order to boost their efficiencies and competitive advantages. Tidd & Bessant (2009, pp. 3-50), extend this category by identifying two more types of innovations namely, paradigm innovation, and position innovation.

The later involves changing the mental models that shape organizational behavior and activities, whereas the former refers to the modification of the context in which new or improved products are launched.

By considering the degree of change, Goffin & Mitchell (2010, pp. 1-40) identify two types of innovations namely, radical and incremental innovation. Radical innovation is associated with the use of breakthrough ideas or techniques to create new products or processes.

Radical innovation often creates new markets or modifies existing ones through introduction of superior products. Incremental innovation, on the other hand, involves making small but important improvements to existing products or process in a consistent manner.

Managing Innovation

Tidd & Bessant (2009, pp. 3-50) characterize innovation as a continuum in which minor changes occur at one extreme end, whereas radical changes take place on the other extreme end. Thus, incremental changes occur at the center of these two extremes.

Goffin & Mitchell (2010, pp. 1-40) agree with this perspective by asserting that innovation occurs through a series of phases. This progression occurs irrespective of the type of innovation. According to Goffin & Mitchell (2010, pp. 1-40), innovation is an organization wide exercise rather than the preserve of the research and development (R&D) department.

Consequently, important departments such as human resources management, finance, marketing, and operations among others should actively participate in innovation. This facilitates creation of synergies through sharing of ideas and resources (Reiss 2012, p. 67).

Innovation requires an effective leadership since it is a change process. Furthermore, the leadership must develop an effective innovation strategy.

According to Goffin & Mitchell (2010, pp. 1-40) the implementation of the innovation strategy include tasks such as assessing the influence of market trends on the need for innovation, as well as, the role of technology in the process of innovation.

Moreover, the management must create awareness about the role of innovation among the employees and align the available resources to the innovation strategy. In this regard, innovation requires a framework that enables organizations to match technical expertise with their employees’ soft skills.

Apart from formulating a strategy, the following elements of innovation must be managed. First, a pool of ideas must be generated through strategies that encourage creativity. Concisely, creativity should enable the organization to utilize both internal and external knowledge to innovate.

Good ideas should enable the organization to take into account the technical, customer, and market needs in its decisions (Goffin & Mitchell 2010, pp. 1-40).

Second, a prioritization mechanism that involves analysis of risks and returns must be available to enable the organization to choose the right ideas.

Third, the implementation of the innovation should take the shortest time possible. The implementation stage includes processes such as prototyping, testing, and commercialization.

Finally, innovation requires effective management of human resources (Goffin & Mitchell 2010, pp. 1-40). This involves adopting effective staffing and training policies, as well as, creating functional organizational structures and a culture of innovation.

Change

Change is the process through which business strategies or departments of a company are modified in response to the prevailing market or industry trends (Kuntz & Gomes 2012, pp. 250-256). Change occurs in nearly all organizations, and its effects can be negative or positive.

Some of the aspects of an industry that are likely to change include regulations, technology, and resource availability. Thus, change management is the process of handling these alterations in a systematic manner. The aspects of change management include the following.

First, it involves identifying and introducing new values, norms, and behaviors that will facilitate execution of business activities using improved techniques (Kuntz & Gomes 2012, pp. 250-256). Second, it involves building consensus among stakeholders concerning the changes designed to satisfy their needs in a better manner.

Finally, change management involves planning, testing, and implementing the processes that are associated with the transition from one business model to another.

Lewin’s Force Filed Model

According to Lewin’ model, organizational behavior is determined by “the dynamic balance of two forces namely, driving and restraining forces” (Bernard 2004, pp. 23-45). Change occurs when the balance between these forces shifts in either direction.

Driving forces are those that facilitate achievement of the required change. Restraining forces, on the other hand, are the factors that hinder achievement of the desired change. The two forces create a state of equilibrium in the organization.

Concisely, no change will occur if the magnitudes of the two forces are equal. Thus, a change in the magnitude of one of the forces will create a new balance or quasi-equilibrium, which represents organizational change.

According to Lewin’s model, successful change occurs in three phases namely, unfreezing, moving, and refreezing (Bernard 2004, pp. 23-45). Unfreezing occurs when the equilibrium between the forces is destabilized.

Movement involves altering the driving and restraining forces in order to achieve the desired change. At the refreezing stage, behaviors that promote positive change are reinforced in order to sustain the achieved change.

The strengths of Lewin’s model are twofold. First, it provides a useful framework that enables organizations to scan their environments in order to identify impending changes. These changes are essentially the threats and opportunities in an organization’s environment (Bernard 2004, pp. 23-45).

In this regard, the model helps organizations to plan and implement the type of change that will enable them to take advantage of opportunities and minimize threats. S

econd, the model enables organizations to plan for the utilization of the available resources in preparation for the impending change. Concisely, resource planning is often easy if their intended use is known in advance.

Despite its importance in planning, Lewin’s model has the following weaknesses. First, change is not always achieved by influencing the behaviors of the members of an organization. This is because change can occur due to external factors such as the emergence of new technologies or enactment of new regulations.

For example, a law that prohibits the use of coal will force a manufacturing firm to change its production technique without necessarily convincing the firm’s members to embrace the change.

Second, creating change by diminishing the restraining forces can cause harmful tensions due to the competing perspectives of the individuals who are supporting change and those who are opposing it (Bernard 2004, pp. 23-45). The party that loses in this competition can develop low morale, thereby limiting the possibility of achieving the change.

Third, the movement phase ignores the roles of non-human resources such as financial capital in the process of implementing change. Concisely, it is unrealistic to implement change by simply influencing stakeholders’ behaviors. Non-human resources and technical processes are also important at the implementation stage.

Finally, the freezing stage focuses on maintaining the already achieved change rather than promoting advancement of the change process. In this regard, the culture of change can be lost as the organization focuses on maintain the new status quo.

Haye’s Theory

Haye (2010, pp 41-55) extended Lewin’s force-field theory by developing a change model that consists of eight stages. The first stage involves identifying the need for change. This stage involves influencing people’s attitudes towards change, interpreting the business environment and making decisions to change the status quo.

The second stage involves commencing the change process by creating a desire for change among stakeholders. The third stage entails a diagnosis process in which the current state is examined in order to identify the weaknesses of the organization. This leads to the fourth stage in which the change vision is developed.

The fifth and the sixth stage involve preparing and planning for implementation (Haye 2010, pp 41-55). The tasks that must be completed, as well as, the time and the recourses that are needed to implement the change are identified at this stage.

At the seventh stage, the change is implemented. Furthermore, monitoring and control measures are put in place to guarantee achievement of the desired outcome. The last stage involves maintaining gains in order to sustain the change. Additionally, attempts are made to improve the change.

Heye’s model has the following strengths. To begin with, it addresses the weakness of Lewin’s refreezing stage which focuses on maintain the already achieved gains. In this regard, Heye’s model enables organizations to improve their competitiveness by approaching change as a continuous process (Reiss 2012, p. 134).

The model highlights the importance of monitoring and control mechanisms in the implementation stage. These mechanisms help organizations to identify mistakes and to take corrective actions in time, thereby preventing failure.

Finally, the model improves Lewin’s theory by identifying additional resources that are necessary for successful implementation of change (Haye 2010, pp 41-55). Concisely, it recognizes the importance of taking into account time and non-human resource constraints at the implementation stage.

The main flaw in Heye’s model is that it focuses only on planned change. In reality, the application of planned change is difficult due to the complications associated with predicting future changes.

Besides, using a rigid blueprint to introduce change limits the organization’s ability to take into account emerging changes or concerns during the implementation stage. Heye’s model cannot be used to address unexpected changes or situations that require urgent response.

This is because there will be not adequate time to prepare a blueprint for the change (Reiss 2012, p. 141). Moreover, it is not possible to plan for a change that is not expected to occur. The other weakness of the model is that it lacks a clear framework for change management.

Much of the tasks in stage two and three occur at the first stage. Concisely, reviewing the current state (stage 3) and commencing the change process (stage 2) are essentially part of the first stage. Moreover, monitoring is done only during the implementation stage.

Ideally, monitoring and evaluation should continue even after implementation in order to identify opportunities for improvements.

Kotter and Cohen’s Model

Kotter & Cohen (2002, pp. 1-13) also developed a change management model that consists of eight stages. In this model, change begins with the creation of “a sense of urgency among relevant people” (Kotter & Cohen 2002, pp. 1-13).

A guiding team is established in the second stage to lead the change process. This team consists of individuals with advanced technical and leadership skills, as well as, adequate authority and connections. In the third stage, the guiding team develops a clear vision for the desired change.

They also formulate strategies to facilitate achievement of the vision. At the fourth stage, the guiding team communicates the vision to all stakeholders in order to improve their understanding of the impending change. The obstacles that are likely to hinder the achievement of the vision are eliminated at the fifth stage.

The sixth stage focuses on creating short-term wins to encourage members of the organization to continue with the change. In the seventh stage, the pursuit of the vision is intensified through achievement of a series of changes. In the last stage, the guiding team creates a new culture that sustains the change.

The main strength of this model is that it emphasizes the importance of creating and communicating a clear vision for the change. A clear vision is important because it enables organizations to focus on the stated change objectives.

The model also highlights the importance of effective teamwork in the process of implementing change. A team of highly skilled individuals is likely to generate enough ideas in order to translate the vision into reality (Kotter & Cohen 2002, pp. 1-13).

Finally, by creating a new culture at the last stage is likely to sustain the change, especially, if the members of the organization identify with culture.

Despite its strengths, the model has some flaws. To begin with, entrusting the change process with a few ‘relevant’ members of the organization can cause isolation of employees and resistance to change.

Moreover, creating a sense of urgency is all about influencing the perspective of the entire organization about the change rather than convincing a few ‘relevant people’ to accept the change (Bent, Paauwe & Williams 1999, pp. 377-404).

Even though the relevant people might develop the sense of urgency, change might not occur if other members of the organization reject it. Finally, creating short-term wins can lead to premature celebrations, thereby jeopardizing achievement of the vision.

Concisely, members of the organization might relax after the first achievements, thereby losing their focus on the vision.

The main similarity of the three models is that each of them focuses on change management through a series of stages. Hence, they conceptualize change as a continuous process.

However, the activities associated with each stage vary from model to model. The other similarity is that they focus on sustaining change by reinforcing achieved gains.

Theory E

The aim of this theory is to facilitate creation of economic value in line with the expectations of the shareholders. According to this theory, creation of economic value is the most important objective of the firm (Beer & Nohria 2000, pp. 1-31). Thus, economic value is the only objective that firms should pursue.

Additionally, financial incentives are used to motivate members of the organization to achieve the sole objective of creating economic value. Leaders using this theory focus on changing the organization’s strategies, structures, as well as, systems.

Since these aspects of the organization can readily be changed, quick financial results can be achieved. Since market expectations drive change, the change process must be pragmatic and well planned. In order to develop these plans, the organization has to engage large consulting firms for professional advice.

This is expected to enable the organization to realize rapid and outstanding improvements of its economic value.

The main strength of theory E is its ability to facilitate high returns on investments. In this regard, it promotes sustainability since the high returns can be used for further investments and programs that benefit all stakeholders (Kuntz & Gomes 2012, pp. 250-256).

However, the theory has several drawbacks. To begin with, focusing on strategies and systems is less likely to be effective if employees are not involved in the process of changing the organization’s structures (Aitken & Higgs 2010, pp. 41-55).

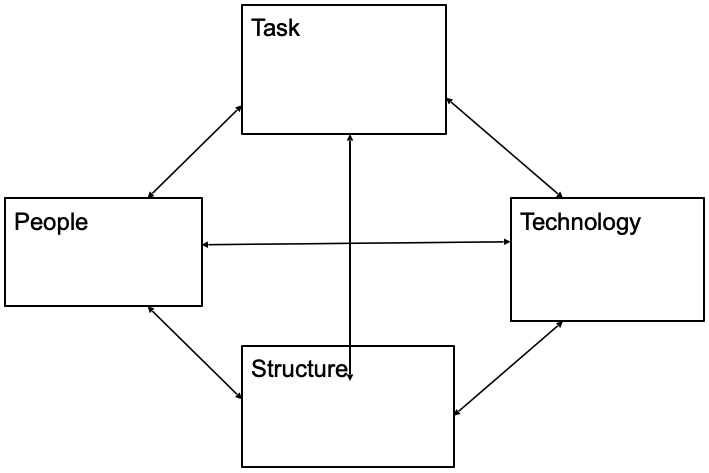

This is because the employees are not likely to identify with structures that are imposed on them. Besides, ignoring the ideas of employees prevents innovation. As illustrated by figure 1 in the appendix, sources of change have diverse characteristics, which can best be articulated through a bottom-up leadership style.

It is apparent that not all organizations can afford the services of large consulting firms. Besides, the solutions developed by the consultants can be ineffective if the needs of the organization are not clearly understood.

While financial incentives can motivate achievement of change, skill-based incentives have to be implemented to facilitate innovation. Skill-based incentives will promote acquisition of advanced skills that must exist if meaningful innovation is to be achieved (Beer & Nohria 2000, pp. 1-31).

Finally, the theory provides a narrow view of the firm. In modern economies, objectives such as corporate social responsibility (CSR) and good corporate governance are just as important as the financial objective. Thus, the financial objective cannot be considered in isolation of other objectives that often facilitate its achievement.

Theory O

According to theory O, the purpose of change is to enable an organization to develop capabilities such as employees’ ability to identify and solve problems.

In this regard, the main objective is to develop a work system that promotes emotional commitment among employees in order to improve the firm’s efficiency and effectiveness (Beer & Nohria 2000, pp. 1-31).

Thus, the management has to articulate and promote the values and behaviors that inform the organizational culture and emotional commitment. Theory O advocates for non-pragmatic and emergent planning for change.

Planning is led by the employees and is done through experiments, which facilitate innovation. Engaging employees enhances motivation; thus, financial incentives only play a supplementary role in improving morale. Proponents of theory O prefer a consulting model that focuses on process.

The rationale of this preference is based on the premise that small projects and engagement of a handful of consultants will facilitate a lasting cultural transformation that promotes innovation.

The main strengths of theory O is that its focus on organizational culture helps in implementing a lasting change, which all stakeholders identify with (Kotter & Cohen 2002, pp. 1-13). By promoting commitment among employees, innovation can be achieved even in the absence of financial incentives (Filippetti 2011, pp.32-45).

Additionally, it is easier to innovate if emerging issues are taken into account during the planning process. Similarly, a consultancy model that focuses on process promotes innovation by enhancing employees understanding of new processes.

Theory O is often criticized due to the following flaws. To begin with, the fact that non-financial objectives are important does not mean that organizations should not focus on creating economic value. It is apparent that a firm that performs poorly in terms of returns on investments will be less attractive to investors.

Besides, poor financial performance will hamper the implementation of programs that promote commitment among employees. In this context, theory O cannot promote sustainability in the long-run. Cultural transformation and development of emotional commitment often take a long time.

Thus, theory O cannot be used to implement revolutionary change. Finally, ignoring expert advice from consultants can hurt the organization. In most cases, product and process innovation requires expert advice, which can only be obtained outside the organization (Von & Stamm 2009, pp. 49-66).

Leadership of Change and Innovation

According to Balogoun & Hope (2008, pp. 20-59), change can only be successful if there is a person who is responsible for leading it. In this regard, Balogoun & Hope (2008, pp. 20-59) identified the following change roles. First, there must be a change champion.

This can be the CEO, or the MD of the company. Second, there must be external facilitation. Concisely, organizations should hire external consultants to provide expert advice during the change process. Third, a change action team has to be created to lead the change process.

Finally, there must be functional delegation. In this case, the change responsibility is delegated to a given department such as human resource management.

External consultants can provide useful advice that leads to the achievement of the desired change because most of them have vast experiences and knowledge. However, they can be very expensive, thereby limiting the ability of organizations to access their advice.

In some cases, external consultants may lack accountability or may fail to understand the organization’s needs. In this situation, consultants are likely to give misleading advice. The benefit of establishing a change team is that it facilitates generation of ideas and ownership of the change process (Von & Stamm 2009, pp. 49-66).

However, making decisions in a large team can be time consuming due to the need to build consensus among the members. Moreover, entrusting the change process with only one department is likely to cause failure. This is because change is a multidimensional process that requires the input of all departments.

Aitken & Higgs (2010, 41-55) also identified four change roles namely, change advocates, change sponsors, change agents and change targets. The role of the change advocate is to initiate the change process. The skills needed in this role include ability to scan the environment in order to identify the need for change.

Change sponsors are expected to support the change process. Thus, they should have networking skills. Change agents are responsible for the implementation of the change. This role requires ability to manage change plans and process.

The strength of Aitken and Higgs’ theory is that it highlights the skills that are necessary in each role. One of the weaknesses of the model is that it does not illustrate the interdependencies between the change roles.

For example, the change advocate must consistently work with the change agents to ensure that the implementation process is aligned to the vision.

According to theory E, change and innovation should be led a through a top-down leadership approach. The leader does not involve his or her management team and other employees in making key decisions (Beer & Nohria 2002, 1-31).

The rationale of this approach is that the delays associated with consultations during decision-making can be avoided. In addition, the organization can avoid the risk of entrusting lower-level staff with the responsibility of making strategic decisions during turbulent times.

The weakness of the top-down approach is that leading change requires a powerful coalition that consists of change advocates, targets, sponsors, and agents (Aiteken & Higgs 2010, pp. 41-55). The leader cannot achieve a meaningful change by excluding the coalition members.

A top-down approach also jeopardizes innovation by discouraging ideation among employees. Finally, a top-down approach exposes the organization to the risk of failure, especially, if the leader is not a visionary and an effective change advocate. His failure to consult other members of the organization will certainly lead to failure.

Proponents of theory O believe that effective leadership of change and innovation should involve collaboration with employees. Thus, employees should be actively involved in identification of problems and finding solutions to such problems (Beer & Nohria 2002, 1-31).

As illustrated in figure 3 in the appendix, change affects various organs of the organization. Thus, involvement is needed to facilitate creation of trust, and commitment (Okurume 2012, 78-82). It also promotes ideation, which informs innovation.

Besides, long-term change can be achieved if the employees are committed to the change process. However, participative leadership can be a slow way of achieving change.

Issues of Politics and Stakeholder Engagement

Power concerns the “capacity of individuals to exert their will over others, while political behavior is the practical domain of power in action, worked out through the use of techniques of influence” (Senior & Swailes 2010, pp.177-221).

Thus, power is the ability to influence a person or a group of people to adopt a given perspective. In this regard, power refers to the capacity to get things done and to avert resistance to change. Senior & Swailes (2010, pp. 177-221) identified five sources of power namely, positional, expert, referent, reward and coercive power.

Reward power can lead to change through push and pull strategies. Push strategies involve influencing people to accept change by withholding rewards from those who are resistant to change. This strategy is likely to fail in organizations with high levels of democracy.

Democracy allows people to make choices, thereby limiting the managements’ ability to impose change on people. Pull strategies use material and social rewards to facilitate change. Even though rewards can encourage members of the organization to support change, the underlying cost implication can limit its use.

Stakeholder engagement advocates for active involvement of all concerned parties in the change process. However, negative use of power can result into conflicts among the stakeholders, thereby grounding the change process to a halt.

Conflicts usually occur due to poor communication and unwillingness to accept divergent opinions (Senior & Swailes 2010, pp.177-221). The source of power determines the level of stakeholder involvement. Change agents with expert power are likely to encourage stakeholder engagement.

This is because using expert power necessitates sharing of knowledge and ideas, and this facilitates stakeholder engagement. In authoritarian organizations, using positional power can result into alienation of stakeholders in the change process. This is because authoritarian leaders do not believe in consultations.

Poor stakeholder management often results into covert political action such as sabotage, and theft (Senior & Swailes 2010, pp.177-221). These actions are often defined as deviant behaviors rather than organizational politics.

This perspective can lead to failure because it ignores the underlying conflicts that lead to covert political action. Concisely, proscribing covert political action can limit the organization’s ability to understand stakeholders’ concerns. Thus, addressing resistance to change will be difficult.

Examples of Change

Successful Change

The customers and the employees of the bank that I work for had difficulties in finding information from the company’s website. Customers could not easily access product information and manage their accounts through the internet. The employees, on the other hand, were not able to access information about company activities.

As a manager, I saw the need to change the bank’s website in order to improve its usability. The change that was needed was to improve the availability of information on the bank’s website and the ability to access it, especially, from remote locations.

The change was achieved through incremental innovation because we simply improved the performance of the website rather than constructing a new one. This involved using advanced internet technology. Thus, the introduced change was a technological one.

The success of this change can be attributed to the following factors. To begin with, I was able to identify the need for change and to create a sense of urgency. According to Lewin’s model, successful change begins with the unfreezing stage in which the need for change is identified.

Kotter & Cohen (2002, pp. 1-13) assert that a sense of urgency must be created in order to motivate others to accept change. Even though Kotter & Cohen (2002, pp. 1-13) argue that a powerful coalition must be built to ensure change, I did not establish any alliance.

This refutes the claim by Kotter and Cohen (2002, pp. 1-13) that change must be supported by a specific number of people for it to succeed. The change team consisted of eight experts from the bank.

This is contrary to the perspective of Balogun and Hope (2008, pp. 20-60) who believe that external facilitation is a necessary condition for change. One factor that enhanced the success of the change was effective planning. A blueprint that highlighted the details of the change was used in the implementation stage.

This strategy confirms the perspective of Heye (2010, pp. 41-55) who opines that a master plan is necessary for successful implementation of change. Through periodic improvements of the website, we have been able to sustain the change.

This observation confirms the premise that continuous improvements lead to sustainable change (Heye 2010, pp. 41-55).

Less Successful Change

As the bank manager, I decided to renovate all the 32 branches of the company in response to market demands. The aim of this change was to make the branches trendy and to reduce the time spent to serve customers.

The change that was needed involved improving the ambiance of the branches and modifying the procedures for serving customers. Thus, the change was introduced through incremental process innovation. However, the change was not successful due to the following reasons.

To begin with, the risks associated with the implementation of the change were not taken into account. Concisely, financial constraints prevented us from implementing the change in all branches.

This confirms the findings of Kotter (1995, pp. 1-18), which states that failure to remove obstacles in the change process can lead to failure. According to lewin’s force filed model, change is likely to fail if the restraining forces exceed the driving forces.

In our case, the change was not fully funded because the finance department believed that it was very expensive and had little return on investment. This observation illustrates the importance of winning the support of relevant people in the change process (Kotter & Cohen 2002, pp. 1-13).

Concisely, we could have accessed enough funds by convincing the finance department to support the change. Finally, the change failed because I declared victory too early. Initially, the employees increased their productivity, thereby reducing the time spent to serve customers.

However, the first wave of change created a feeling that success had been achieved. Thus, the employees reduced their effort before the achievement of the vision. This observation confirms Kotter’s view that declaring victory too early leads to failure.

Assessment of My Leadership Skills

My strengths as a change leader include the following. First, I have the ability to create a sense of urgency for change. A sense of urgency is always needed to motivate colleagues to assist in implementing the change (Heye 2010, pp. 41-55).

For example, I successfully led the process of improving the bank’s website by creating a sense of urgency. Second, I always develop a clear vision for the intended change. Besides, I often communicate the change vision clearly to the concerned stakeholders.

Third, I have been able to systematically plan for change. This strategy is one of the main factors that led to the successful change of the bank’s website. Finally, I always focus on evolutionary change that aligns the change to the organization’s values and norms.

This helps in creating a lasting change that is well integrated into the organizational culture (Aitken & Higgs 2010, pp. 41-55).

My weaknesses include the following. I often fail to build a powerful coalition to guide the change process. In particular, I sometimes fail to get the minimum number of people that would effectively support me in the change process. Kotter & Cohen (2002, pp. 1-13) assert that failure is likely to occur if a powerful coalition is not built to lead it.

Another challenge has been the inability to remove obstacles in the change process. This often happen since some obstacles cannot be foreseen and addressed in time. For example, renovating the bank’s branches failed due to financial constraints.

Finally, I sometimes declare victory too early; thus, I often quite the change process before it deeply sink in the organization’s culture. This explains our failure to sustain the culture of high productivity in order to reduce the time we spend to serve customers at the bank.

Action Plan

One of my leadership weaknesses is inability to build a powerful coalition. This weakness will be addressed by focusing on stakeholder engagement and improving my communication skills. Stakeholder engagement will enable me to identify and include the relevant people in the change process.

Advanced communication skills will improve my ability to convince the relevant people to support the change (Kotter & Cohen 2002, pp. 1-13). My second weakness is inability to remove obstacles in the change process. I will address this weakness by acquiring risk management skills.

These skills will enable me to identify potential obstacles in the change process. Additionally, I will focus on working with external consultants in order to access expert advice on how to eliminate obstacles. The last weakness is declaring victory too early.

In this regard, I will focus on creating short-term wins in order to motivate members of the organization to continue with the change. Furthermore, I will focus on convincing the employees to improve their efforts until the desired vision is achieved.

In this case, short-term wins will be a means of creating high morale rather than a sign of early victory.

Conclusion

Change and innovation are essential and inevitable in every organization. In order to realign themselves to market dynamics, organizations must consistently innovate and implement change. Successful change and innovation depends on how well the process is led by the change advocate (Heye 2010, pp. 41-55).

Additionally, the theory that informs the innovation and change process determines success. Generally, there are several change and innovation models or theories. Each of these theories has its weaknesses and strengths as discussed earlier.

Thus, the change advocate must always make deliberate efforts to address the weaknesses of the adopted theory.

Appendix

Figure 1

Features/ characteristics of sources of change

Figure 2

Gross expenditure on R&D in the UK (£ million)

Table source: Office for National Statistics

Figure 3

Impact of organizational change

References

Aitken, P, & Higgs, M 2010, Developing Change Leaders, BH Press, London.

Amabile, M 1997, ‘Motivating Creativity in Organizations: Doing What You Love and Loving What You Do’, California Management Review, vol. 40 no. 1, pp. 39-58.

Balagun, J & Hope, H 2008, Exploring Strategic Change, Financial Times Prentice Hall, New York.

Barcan, L 2010, ‘Change Management of Organization in the Knowledge Economy’, Economic Science Series, vol. 3 no. 38, pp. 6-7.

Beer, M, & Nohria, N 2000, Breaking the Code of Change, HBS Press, Boston.

Bent, J & Paauwe, J & Williams, R 1999, ‘Organizational Learning: Exploration of Organizational Memory and its Role in Organizational Change Processes’, Journal of Organizational Change Management, vol. 12 no. 5, pp. 377-404.

Bernard, B 2004, ‘Kurt Lewin and the Planned Approach to Change’, Journal of Management Studies, vol. 41 no. 6, pp. 23-45.

Filippetti, A, 2011, ‘Innovation Modes and Design as a Source of Innovation: Firm-Level Analysis’, European Journal of Innovation Management, vol. 14 no. 1, pp. 32-45.

Goffin, K, & Mitchell, R 2010, Innovation Management, Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Hayes, J, 2010, The Theory and Practice of Change Management. Palgrave Macmillan London.

Imtiaz, S 2012, ‘Change Management’, Journal of Applied Management and Investments, vol. 1 no. 3, pp. 326-332.

Kotter, J, 1995, Leading Change: Why Transformation Efforts Fail, Harvard Business School Press London.

Kotter, J, & Cohen, D 2002, The Heart of Change, HBS Press, London.

Kuntz, J, & Gomes, J 2012 ‘Transformation Change in Organizations: A Self-Regulation Approach’, Journal of Organizational Change Management, vol. 25 no. 1, pp. 13-24.

Norgrasek, J 2011, ‘Change Management as a Critical Success Factor in E-Government Implementation’, Business Systems Research, vol. 2 no. 2, pp. 13-24.

Okurume, D 2012, ‘Impact of Career Growth Prospects and Formal Mentoring on Organizational Citizenship Behavior’, Leadership & Organization Development Journal, vol. 33 no. 1, pp. 78-82.

Reiss, M 2012, Change Management, McGraw-Hill, New York.

Senior, B & Swailes, S 2009, Organizational Change, Prentice Hall Financial Times, New York.

Tidd, J & Bessant, J 2009, Managing Innovation, Wiley, London.

Von, S 2009, Managing Innovation, Design and Creativity, John Wiley and Sons, New York.