Abstract

This paper investigates the effects of mergers and acquisitions on the operating performance and shareholder wealth of EU firms. It analyses a vast amount of literature to explain the main theories underlying the occurrence of mergers and acquisitions and their potential effects on participating firms. As an accounting study, this paper conducts a pre-merger and post-merger analysis of four EU firms. These firms operate in the telecommunications sector, automobile sector, and the chemical industry. The paper obtains quantitative data regarding the financial performance of the four companies from their financial statements, business reports, and financial websites.

Using these techniques, this paper demonstrates that most mergers and acquisitions benefit the shareholders of target firms by increasing the value of their investments. However, shareholders of acquiring firms do not enjoy the same benefit. Therefore, this paper demonstrates that most mergers and acquisitions create shareholder value in a biased manner. However, most companies that engage in mergers and acquisitions benefit from increased operational performance. Particularly, this paper highlights increased economies of scale and cost reductions as significant benefits enjoyed from mergers and acquisitions.

Using a theoretical framework that conceptualizes the effects of mergers and acquisitions, this paper explains the above analogy through the market power theory, agency theory, free cash flow theory, and synergy theory. For example, through the market power theory, this paper shows that different companies pursue mergers and acquisitions to increase their market dominance. Comparatively, using the free cash flow theory, this paper explains that most managers pursue mergers and acquisitions when they have excess cash flow. Overall, based on an assessment of four EU mergers and acquisitions, this paper shows that most of the benefits enjoyed by companies from mergers and acquisitions are not “highly significant” to the shareholders. Therefore, mergers and acquisitions in the European Union do not provide wholesome shareholder values to the shareholders.

Introduction

This chapter is the first section of this dissertation. It contains an overview of the research topic and detailed elements of the focus of the study. The main purpose of this chapter is therefore to explain the background of the study, the research aim, the research objectives, and the structure of the dissertation.

Mergers and acquisitions (M&A) are important corporate strategies that most companies use to grow their business portfolios, without starting new businesses, or creating new business subsidiaries (Kaplan 2006). M&A transactions entail different strategies that are limited to dividing, purchasing, or selling corporate entities to achieve a specific business goal (Kaplan 2006). However, many scholars and researchers contradict both concepts, based on their expected economic outcomes (Sherman & Hart 2006). However, to demystify both concepts, it is crucial to understand that, legally, mergers comprise of a union between two or more companies, while acquisitions define a hostile approach of company takeovers (Sherman & Hart 2006).

In acquisitions, companies eliminate the existing target companies by establishing new business entities (sometimes, the acquired company may maintain its legal existence, but often, the purchasing company controls its operations) (Kaplan 2006). Atkeson & Burstein (2008) explain that most mergers and acquisitions result in the economic or financial consolidation of participating companies. In this context, it is important to understand that M&A transactions have different “undertones.” For example, mergers often emerge from the consolidation of mutual interests, while acquisitions occur from the dominance of one interest (usually of one company) (Sherman & Hart 2006).

When two companies realize that a merger between their companies would result in an improvement of their overall interests, experts term such a union (if it happens) as a “merger of equals” (Focarelli & Pozzolo 2008). Such unions are often friendly. However, acquisitions are unfriendly because they often involve one company that does not wish to merge with another company.

Recent decades have seen a proliferation of M&A activities around the world. The increase of M&A activities adds to the expanding history of similar transactions that started during the formation of companies (Sherman & Hart 2006). Among the earliest forms of M&A activities occurred in America in the late 19th century (Baker & Kiymaz 2011). However, over the decades, M&A activities have spread across the world. For example, beyond America, Indian companies started to adopt the same strategy in the 1700s (Baker & Kiymaz 2011). Illustratively, in 1708, East India Company (an international trade company) merged with one competitor and established a dominant position in the Indian trade (Focarelli & Pozzolo 2008).

Similar notable companies that merged in the 1700s include the Italian Monte dei Paschi and Monte Pio Bank, which merged to establish among the greatest banking entities of their time (Focarelli & Pozzolo 2008). After these mergers, a larger and greater movement of M&A activities started in about 1895 and ended in 1905 (Baker & Kiymaz 2011). This first wave of mergers mainly comprised of horizontal mergers (mergers comprising of firms in the same industry).

The second wave of mergers occurred from 1916-1929 (Baker & Kiymaz 2011). This wave of mergers mainly comprised of vertical mergers and paved the way for the third wave of mergers that included diversified conglomerate mergers (Baker & Kiymaz 2011). This third wave of mergers occurred for about four years (between 1965 and 1969) (Deminor-Rating 2005). The diversified conglomerate mergers later paved the way for the fourth wave of mergers, which included congeneric mergers. Some researchers say most companies experienced hostile takeovers during this period (1981-1989) (Baker & Kiymaz 2011; Atkeson & Burstein 2008). With the onset of globalization, cross-border mergers dominated the fifth wave of mergers that occurred between 1992 and 2000 (Baker & Kiymaz 2011). Academically, the last wave of mergers (sixth wave of mergers) occurred between 2003 and 2008 (Baker & Kiymaz 2011). These mergers mainly comprised of private equity mergers (mainly supported by shareholder activism) (Deminor-Rating 2005).

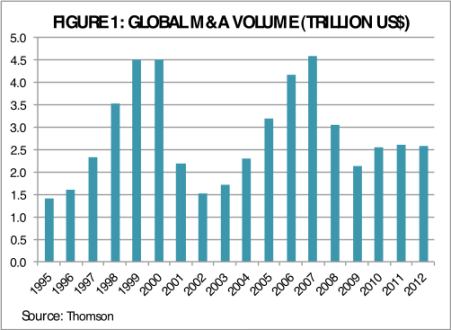

Besides the nature and characteristics of global mergers and acquisitions, a significant center of interest that dominates industrial and financial economics is the value of these M&As. Data from the graph below shows that the total value of M&A transactions (globally) runs into trillions of dollars.

Similarly, based on the above graph, the total volume of M&A transactions has varied throughout history. The highest volumes occurred in the late 1990s and mid-2000s. Indeed, between 2004 and 2009, the global M&A transactions increased significantly. Independent of the above graph, the Institute of Mergers, Acquisitions, and Alliances (2013) says the total value of the ten biggest global mergers and acquisitions in the world (in the nineties) amounted to about $760 billion. The highest valued merger involved Vodafone Airtouch PLC and Mannesmann (in 1999). This transaction was worth $202 billion (Institute of Mergers, Acquisitions, and Alliances 2013). In sum, Callaghan & Ho¨pner (2005) say the total value of mergers and acquisitions that occurred in the nineties accounted for about 2% of the global Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

The value of mergers and acquisitions in the 2000s has remained (relatively) the same (as in the 1990s) because the Institute of Mergers, Acquisitions, and Alliances (2013) valued the top ten global mergers in this period and said they amounted to about $759 billion (the total value of M&A transactions in the 1990s was $760 billion). The highest valued merger in the 2000s involved American Online Inc. and Time Warner Company. Analysts valued this merger at $165 billion (Institute of Mergers, Acquisitions, and Alliances 2013). Since 2010, globally, the most notable mergers have involved big multinational companies, such as Google and Motorola (analysts have valued this merger at $9.8 billion) (Forer & Malone 2013). More lucrative mergers have involved Deutsche Telekom, Metro PCS, Softbank, Sprint Corporation, Berkshire Hathaway, and H.J Heinz Company (Forer & Malone 2013). For example, analysts valued the 2012 merger between Deutsche Telekom, Metro PCS at $29 billion (Institute of Mergers, Acquisitions, and Alliances 2013). They have also valued the merger between Berkshire Hathaway, and H.J Heinz Company at $28 billion (Institute of Mergers, Acquisitions, and Alliances 2013).

Research Aim, Objectives, and Hypotheses

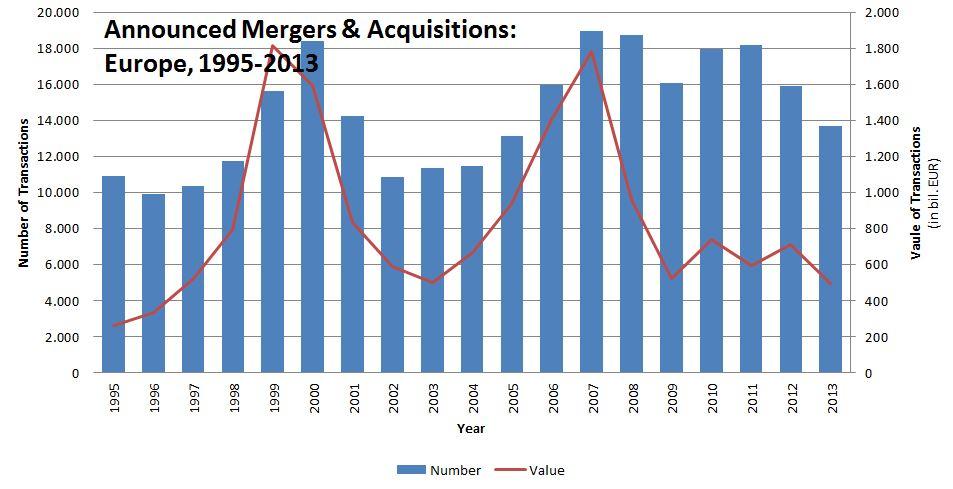

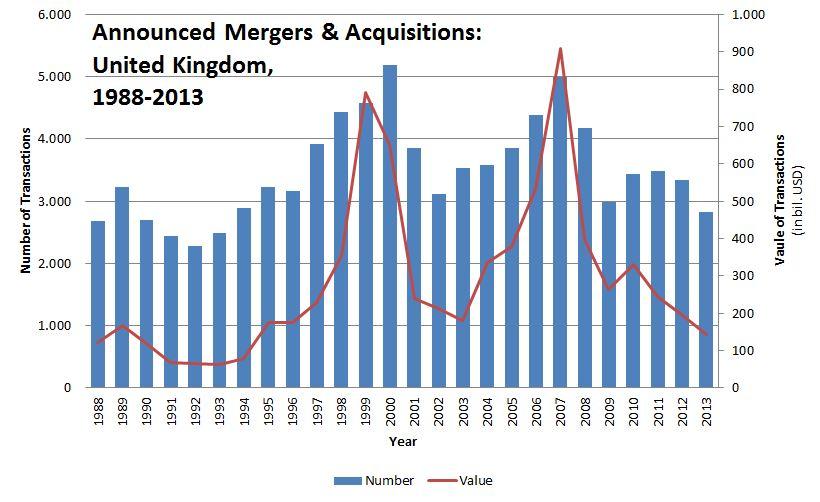

Europe has greatly added to the total global value of mergers and acquisitions. Carr (2004) says, since 1999, Europe has experienced an unprecedented growth of M&A transactions. An analysis of Thomson financial securities data shows that the total value of intra-European mergers and acquisitions (in the 1990s) amounted to about $1.4 trillion (Carr 2004). According to the graph below, the period between 1998 and 2001 accounts for the highest number of mergers and acquisitions in the 20th century. Since 2005, there has been an increase in the volume and value of mergers and acquisitions in Europe. The years 2007 and 2008 accounted for the most valued mergers in Europe, in recent history.

Experts have compared the statistics of European mergers to American numbers and concluded that, for the first time, the recent decade has seen the total value of intra-European mergers and acquisitions match the total value of American mergers and acquisitions (in terms of corporate control) (Institute of Mergers, Acquisitions, and Alliances 2013). However, these statistics mainly represent M&A transactions within the United Kingdom (UK) and the United States (US) (Goergen & Marina 2005). This paper adopts a different focus of analysis by focusing on the effects of mergers and acquisitions within the European Union (EU).

Aim of the Research

To establish the effects of mergers and acquisitions on operating performance and shareholder wealth of firms

Objectives of the Research

- To find out the effects of mergers and acquisitions on the operating performance of European firms

- To investigate the effects of mergers and acquisitions on the shareholder wealth of European firms

Hypothesis

- H1: Mergers and acquisitions improve the operational performance of European firms

- H2: Mergers and acquisitions increase the shareholder wealth of European firms

Motivation for Conducting the Research

As mentioned in this chapter, most research studies have focused on investigating the effects of mergers and acquisitions on UK and US firms. Moreover, the existing studies report contradicting findings for the performance of UK and US firms (Baker & Kiymaz 2011; Atkeson & Burstein 2008). Some say mergers and acquisitions improve the operational performance of these firms, while others claim a reduction of operational performance from M&A agreements (Baker & Kiymaz 2011; Atkeson & Burstein 2008). Interestingly, some studies report that most mergers and acquisitions do not have a significant impact on the operational performance, or shareholder wealth, of the concerned firms (Baker & Kiymaz 2011). Again, it is important to mention that most of these findings largely reflect the outcomes of the UK and US studies. From this bias, there is little empirical evidence to explain the operational performance of European firms, in isolation.

European firms pose an interesting platform for analyzing the effects of M&A agreements because most of these firms operate with the economic framework of the European Union. This platform has brought mixed fortunes for many EU countries because of the existence of standardized laws that govern the 28 members of the union (La Porta & Lopez–de–Silanes 2006). This dissertation, therefore, provides a more focused approach to understanding the effects of mergers and acquisitions within this economic block. Indeed, the findings of this study should provide a focused approach to understanding the above relationship because it considers the constitutional nature, governance systems, competition laws, and financial laws that govern EU member states and their firms (La Porta & Lopez–de–Silanes 2006). Through the structure outlined below, this paper seeks to evaluate the effects of mergers and acquisitions on EU firms.

Literature Review

This chapter explores the theoretical background of mergers and acquisitions by focusing on four main theories – free cash flow theory, market power theory, agency theory, and the synergy theory. These theories explain the theoretical underpinning of this paper. Subsequent sections of this paper use these four theories to explain the performance of EU firms.

Theoretical Underpinning

Before engaging in the theoretical understanding of mergers and acquisitions, it is important to understand that most mergers and acquisitions fall into three broad categories – horizontal, vertical, and conglomerate mergers (Buck & Azura 2005). Horizontal mergers involve the union of two or more companies that focus on the same product line (Buck & Azura 2005). Vertical mergers differ from horizontal mergers because they involve the association of different companies that operate at different levels of production (usually in the same product line) (Goffee & Jones 2013). Lastly, conglomerate mergers involve the union of two or more firms that do not operate in the same business/industry (Goffee & Jones 2013). The free cash flow, market power, agency, and synergy theories explain these mergers in detail.

Free Cash Flow Theory

In the late 1980s, Jensen (2007) introduced the free cash flow theory to explain the financial decisions of managers in investing surplus money (excess cash flow). The free cash flow theory stems from the availability of corporate funds, after the deduction of all expenses (Goffee & Jones 2013). Managers often use this fund for purposes of expanding their businesses or paying out dividends to their shareholders (Goergen & Renneboog 2004). However, research shows that many managers prefer to use this excess cash to enter into merger and acquisition agreements (Alfaro & Kalemli-Ozcan 2009). Their incentive may be higher profitability and business advantages that mergers and acquisitions offer (compared to other investments) (UNCTAD 2006).

Occasionally, despite the failure of some investments to increase shareholder value, managers may decide to use these funds to expand businesses (through these mergers and acquisitions) (Carr 2004). They often prefer this option because the second alternative of paying out dividends to shareholders leads to the loss of financial resources and managerial power (Alfaro & Kalemli-Ozcan 2009). The option of pursuing mergers and acquisitions is therefore emerging as an attractive option for most managers because it expands the pool of resources that would be under their control.

The free cash flow theory plays a useful role in understanding the impact of mergers and acquisitions of different organizations because it shows which mergers or acquisitions are likely to fail, and which one would possibly succeed (Alfaro & Volosovych 2007). The free cash flow theory also helps to highlight the nature and solutions of conflicts between shareholders and managers. For example, a common conflict between shareholders and managers is how to spend their excess cash (acquisitions or dividends?). Here, the free cash theory predicts that most managers are likely to undertake projects that have a low benefit to the organization (acquisitions) (Temple & Peck 2002). The same theory also shows that most managers are likely to participate in mergers that are likely to destroy the value of their firms (UNCTAD 2006). For example, diversification is an obvious choice for many managers (UNCTAD 2006). However, it does not generate any immediate gains for organizations.

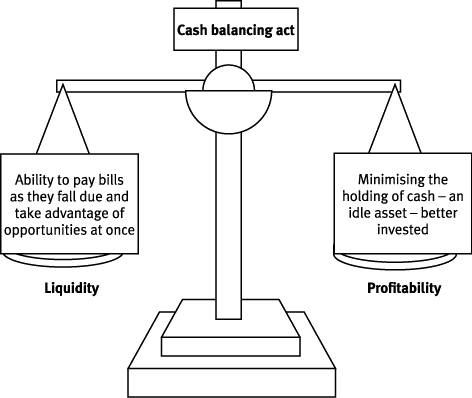

Nonetheless, the main advantage of such strategies is the possibility of future gains, as opposed to the option of investing the same money in unprofitable ventures within the organization (Melitz & Gianmarco 2008). Comparatively, acquisitions (made without stock options) often provide additional benefits to shareholders because it increases the pool of resources under their control (Di Giovanni 2005). This view is true even when such acquisitions create inefficiencies within the organization (Alfaro & Kalemli-Ozcan 2009). Comprehensively, the free cash flow theory outlines a critical cash-balancing act that wavers between profitability and liquidity needs (Helpman & Yeaple 2004). As shown through the diagram below, managers face two real options of meeting current liquidity needs (paying bills) and investing excess cash to increase profitability (minimizing holding cash) by exploiting business opportunities to increase the company’s future liquidity (the latter option often involves pursuing merger and acquisition transactions).

Temple & Peck (2002) say managers who handle huge cash flows often pursue the latter option by preferring to pursue future profitability needs, as opposed to short-term liquidity needs. Declining industries offer a new dynamic to the above analysis because research shows that most mergers that occur within the industry create value, but those that do not occur within the industry create lower values, or, sometimes, no value at all (Alfaro & Kalemli-Ozcan 2009). Firms that operate in the tobacco and energy sectors demonstrate this fact. For example, Lane (2006) says that most tobacco-manufacturing firms lose revenue because of changing consumer habits (but they still enjoy free cash flows that allow them to participate in several acquisition ventures). Most of these firms enjoy excess cash flow but provide very little opportunity for growth (Heinze 2004; Anderson & Van-Wincoop 2004).

These characteristics mean that such companies are good targets for leveraged buyouts. One such example is the $6.3 billion Beatrice LBO merger, which generated excess cash flow through rent, but was limited by existing regulations to expand (Temple & Peck 2002). Because of limited internal investment opportunities, the organization participated in many diverse programs. Overall, the free cash flow theory mainly applies to industries where companies have excess cash flows, but the breakdown of internal policy frameworks, or market limitations, stifle their opportunities for growth (Goldberg 2007). The theory predicts that takeovers occur in such circumstances (Heinze 2004). The theory also predicts the dismantlement of businesses that do not enjoy large economies of scale (Heinze 2004).

The Agency Theory

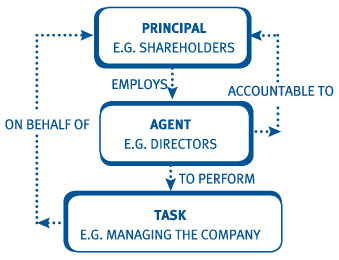

In the early 1970s, Stephen Ross introduced the agency theory to explain the relationship between shareholders and company managers (Fiss & Zajac 2004). A closer analysis of his theory shows that the agency theory shares a close relationship with the free cash flow theory because both theories explain managerial decisions/relationships between shareholders and company executives (Chari & Ouimet 2010). Mainly, the agency theory explains the relationships that exist between principals and their agents (in the context of this paper, the principal is the shareholder, while the agent is the company manager) (Hongxia 2011). The following diagram shows the nature of this relationship

As shown above, the shareholders (principal) employ company directors (agents) to perform a specific task, such as managing a company. Within this relationship, the agents are accountable to the principal. Stated differently, the directors are accountable to the shareholders by performing organizational tasks for the principals (Kaplain Financial Bank 2014). Based on this background, the agency theory provides a framework for understanding managerial and shareholder disputes. For example, Martynova & Renneboog (2006) say, to resolve conflicts between these two parties, companies should refer to the agency theory.

For example, one problem that the agency theory could address is the conflict of interest that may exist between shareholders and company managers (Head & Ries 2005). Another problem that the agency theory could solve is risking tolerance issues between managers and shareholders because shareholders and company executives often have different risk tolerance levels (Kaplain Financial Bank 2014). From this difference, agents and their principals may support opposing strategies of investment. Overall, it is important to understand that agency issues may arise because of insufficient information, or the presence of inefficiencies in an organization (Morgan & Izumi 2005).

One assumption of the agency theory is that selfish interests, in the agency relationship, motivate the decisions of shareholders and company executives (Brealey & Myers 2004). Many researchers attribute the presence of conflicts between these two parties to this fact (Kaplain Financial Bank 2014). Indeed, when company executives pursue self-interests, they often pursue company strategies that conflict, or oppose, the wishes of the shareholders who contracted them (De Pamphilis 2010). The existence of such a possibility draws our attention to a common concept in the agency theory – agency loss.

An agency loss often exists when shareholders get the best possible outcome (in the agency relationship), at the expense of the wishes or interests of company executives (Kaplain Financial Bank 2014; Institute of Mergers, Acquisitions, and Alliances 2013). Often, when company executives disregard their interests and work solely to meet the interests of the shareholders, there is no agency loss. However, when the company executives deviate from the wishes/interests of their shareholders, there is an agency loss (usually, the highest agency losses exist when company executives pursue their self-interests, only) (Brealey & Myers 2004). Evidence from the application of the agency theory (in mergers and acquisitions) suggests that when shareholders and company executives share similar interests, agency loss is minimized (or eliminated) (Kaplain Financial Bank 2014). Research also shows that agency loss is often minimized when shareholders understand the risks posed by the strategic choices made by company executives, during mergers and acquisitions (Brealey & Myers 2004).

The Synergy Theory

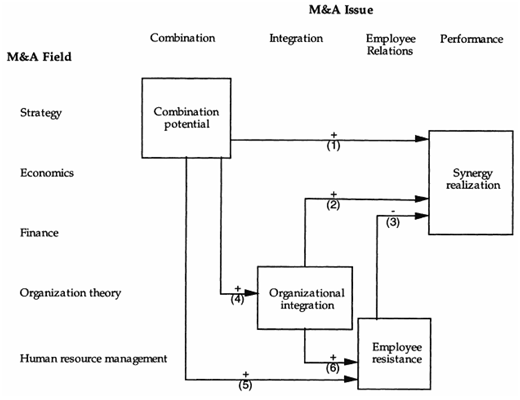

Conventionally, synergy refers to the creation/improvement of competitive capacities when two or more companies work together (Eisfeldt & Rampini 2005). This definition has a significant role in understanding the purpose of mergers and acquisitions because companies often pursue such strategies to improve their synergies (Eisfeldt & Rampini 2005). Broadly, the concept of synergy development in mergers and acquisitions stems from Igor Ansoff’s (a scholar) contributions to the synergy theory (Hackethal & Schmidt 2005). Simply, he explained the theory through a mathematical equation, which suggested the existence of synergy when the benefits of merging are more than the sum of the activities of the merged companies (Thonis 2011). He further explained this concept in the equation, 2+2=5 (Thonis 2011). In perspective, this theory has a lot of significance to merger and acquisition contracts. For example, as shown through the diagram below, synergies may exist through the integration of different M&A concepts.

As shown above, synergies may exist through effective human resource management, implementation of effective strategies, economic integration, financial integration, and the inclusion of organizational theory in management activities (Aguilera & Dencker 2004). These processes lead to the combination of corporate and organizational advantages (Buck & Azura 2005). These advantages create three types of synergies as shown below

Operating Synergy

Operating synergies exist when organizations improve their services, or products, through mergers and acquisitions. Krishnamurti & Vishwanath (2008) say the most common type of operating synergy is the revenue-enhancing synergy. This synergy is more common than cost-reduction synergies (Aguilera & Dencker 2004). However, the realization of these synergies could happen in the short-term, or long-term, depending on the success, or challenges, of a merger, or acquisition.

Financial Synergy

Financial synergies exist when mergers and acquisitions affect the cost of capital for merging firms (Krishnamurti & Vishwanath 2008). Conventionally, companies strive for the reduction of capital costs through the realization of financial synergies. However, other companies strive for the reduction of financial volatilities through the realization of financial synergies (Aguilera & Dencker 2004). For example, a company’s supplier may prefer to do business with a company because it is less risky. This way, financial synergies improve the value of merging firms.

Collusive Synergy

Compared to operating and financial synergies, researchers rarely apply collusive synergy in mergers and acquisitions (Krumm & Dewulf 2008). However, this type of synergy is common in mergers and acquisitions when value creation occurs through the improvement of a firm’s market power. Krishnamurti & Vishwanath (2008) say this type of synergy exists when the redistribution of wealth occurs in an organization. However, it does not lead to the additional creation of economic wealth among firms (Aguilera & Dencker 2004).

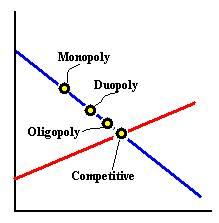

The Market Power Theory

Stephen Hymer introduced the market power theory to explain why many companies engage in merger and acquisition transactions (Masahiko 2005). He said many companies are motivated to enter into such agreements because they want to increase their market power. Particularly, Hymer introduced this theory after evaluating the spirited attempts by multinational corporations to expand their global presence (Copeland 2005). Practical analysis of this theory shows that most firms are motivated to participate in mergers and acquisitions because it helps them to overcome trade barriers and access new markets (Copeland 2005). This action increases their market power.

According to Hymer (cited in Brealey & Myers 2005), mergers and acquisitions emerge from market imperfections. In other words, because market structures deviate from ideal conditions, multinational corporations intervene to correct/exploit these imperfections, through mergers and acquisitions (Brealey & Myers 2005). The following graph shows the continuum through which these multinationals exploit market imperfections.

By merging and acquiring new companies, corporations aim to move higher in the blue continuum (described above) by acquiring a monopolistic status. In other words, such companies achieve a duopolistic, oligopolistic, or monopolistic market structure by consolidating their market positions. However, an ideal market structure would appeal to the competitive position on the graph.

Based on the above analysis, researchers have borrowed Hymer’s concepts to explain cross-border merger and acquisition transactions (Masahiko 2005). Using this theory, these researchers have said companies pursue cross-border mergers and acquisitions because they increase their market powers (Masahiko 2005). Through this strategy, companies expand their collusive networks (that form the pillars for the expansion of their market powers). Similarly, through a reduction of competition (takeovers), the same companies seek to safeguard their market powers (Head & Ries 2007). Under these strategies, the market power theory suggests that cross-border mergers and acquisitions are inherently anticompetitive (The Pennsylvania State University 2014). To explain why companies pursue anticompetitive policies during cross-border mergers and acquisitions, Head & Ries (2007) elaborate that such kinds of ventures are ordinarily risky investments. Therefore, the main benefits companies enjoy by pursuing them is increased control of new investments (market power). However, it is important to understand that firms still expect to reap increased profits in the future.

Research Design and Methodology

The methodology is the systematic analysis of how this research occurred. The methodology may also refer to a set of systems, or methods, that most researchers apply within a specific discipline (Merriam–Webster 2014). This definition informs the view of Merriam–Webster (2014) when she defines methodology as the definition of rules and standards of operation that pertains to a scientific discipline.

Research Design

Salkind (2010) says the most common research designs are exploratory, causal, and descriptive research designs. The exploratory research design applies to studies that have insufficient information about a research problem (Salkind 2010). This research design helps researchers to gain familiarity with a research topic. Comparatively, the causal research design explores the effects of one research variable on another. Researchers have used this research design to explain the relationship between different phenomena, using a causal link between two variables (Salkind 2010). Comparatively, a descriptive research design describes the characteristics of a research issue. For example, this research design explains issues such as “who, what, when, and where” (Salkind 2010). Unlike the causal research design, descriptive research cannot explain why a phenomenon happens; instead, it only describes the phenomenon. This dissertation adopts the causal research design because it investigates the effects of mergers and acquisitions on shareholder value and operational performance of EU companies. To do so, this paper adopts a quantitative approach to analyzing the financial data of four EU companies.

Quantitative research involves the comprehension of the research findings using statistical techniques (Stejskal 2008). The assessment occurs as an accounting study to explain the financial performance of the sampled studies (before and after the mergers and acquisitions). According to Bruner (2002), the greatest strength of the accounting methodology is the credibility of using certified accounting data and the reliability of the information for making financial decisions. For example, analysts use financial data as an indirect measure of economic valuation (Bruner 2002). Comparatively, the main weaknesses of the accounting methodology are backward-looking and the possible absence of comparable data (Bruner 2002).

The existence of non-standard accounting practices (in different companies) may also undermine the reliability of such data. Even though this paper uses a quantitative methodology to support the accounting study, a competing methodology is the qualitative research design. Qualitative research involves making sense of issues by deriving meaning from findings (Stejskal 2008). Unlike the qualitative design, the quantitative approach (used in this paper) provided a wider scope for the collection of financial data.

Data Collection

Most research studies usually use either primary or secondary research methods for data collection. Primary research includes the collection of first-hand information, while secondary research involves the analysis of second-hand information. This dissertation used the secondary research method because it relied on accounting data for past financial performances of EU companies.

Findings and Analysis

M&A Activities within the EU Countries

Austria

Since joining the EU in 1995, Austria has reported a significant rise in the number of M&A transactions. The highest M&A transactions occurred in 2000 and 2007. In 2000, the country reported about 430 transactions and about 460 transactions in 2007. The values of mergers and acquisitions in both years were £30 billion and £32 billion respectively. In 2013, Austria reported about 250 M&A transactions, valued at about £17 billion (Institute of Mergers, Acquisitions, and Alliances 2013).

Belgium

Belgium is a founding member of the EU. The highest number of reported M&A transactions in Belgium occurred in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Particularly, 2000 had the highest number of M&A transactions (about 625) valued at about £90 billion. An analysis of the values and numbers of M&A transactions, between 1991 and 2013, shows that the lowest number of M&A transactions occurred in 1992 and 1994 respectively. Belgium reported about 220 M&A transactions in both years, valued at about £36 billion each. In 2013, the country reported about 260 M&A transactions, valued at about £38 billion (Institute of Mergers, Acquisitions, and Alliances 2013).

Bulgaria

Bulgaria joined the EU in 2007. Since then, the country has reported a marginal increase in M&A activities. For example, in successive years (2009-2011), the number of M&A transactions has increased from 92, in 2009, to 120 in 2011 (CMS 2014). There was a slight drop in M&A activities in 2012 because the country reported only 83 M&A transactions (CMS 2014). However, the value of M&A transactions since joining the EU has steadily increased.

Cyprus

Cyprus joined the EU in 2004. Saikevicius (2013) said since joining the EU, the country has reported 108 M&A transactions (up to 2011). The values of M&A transactions for 2008, 2009, 2010, and 2011 were £1,258 million, £1,017 million, £28 million, and £2,847 million respectively (Global Finance 2014a).

Czech Republic

The Czech Republic joined the EU in 2004. An analysis of the country’s M&A transactions between 2009 and 2012 shows a decline in value (CMS 2014). For example, the value of M&A transactions declined from £3,409 million in 2009 to £1,297 in 2012 (CMS 2014). The numbers of M&A transactions within the same period also replicate the same pattern because the Czech Republic reported 166 M&A deals in 2009 and 102 deals in 2012 (CMS 2014). Within this period, there was a marginal increment in M&A volumes in 2010 (195 transactions) (CMS 2014). Since then, the volumes and values of M&A transactions have steadily declined.

Denmark

Denmark joined the EU in 1973. A recent analysis of the numbers and values of M&A transactions between 2007 and 2013 shows a sporadic trend. In 2007, the country reported £33.9 billion worth of M&A transactions (the highest in the last decade) (Merger Market 2013b). Since 2007, there has been a 21% decrease in the value of M&A transactions. This decline manifests through the decrease in 2011/2012 M&A values (from £10.5 billion to £8.3 billion respectively). The numbers of M&A transactions in 2013 have been low because the Merger Market (2013b) shows that the first and second quarters did not report more than 10 M&A deals.

Estonia

Estonia joined the EU in 2004. Saikevicius (2013) said since joining the EU, the country has reported 25 M&A transactions (up to 2011). In 2013, the country reported 21 M&A transactions. This figure is a slight drop from 2012 because, in 2012, Estonia reported 26 M&A transactions (Baltic Business News 2014).

Finland

Finland joined the EU in 1995. However, an assessment of the country’s recent M&A statistics shows that in 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, and the first half of 2013, the country reported 410, 450, 132, 280, 420, 300, and 240 M&A transactions respectively. These transactions had a value of £52 billion, £43, billion, £15 billion, £24 billion, £60 billion, £30 billion, and £26 billion respectively (Merger Market 2013c).

France

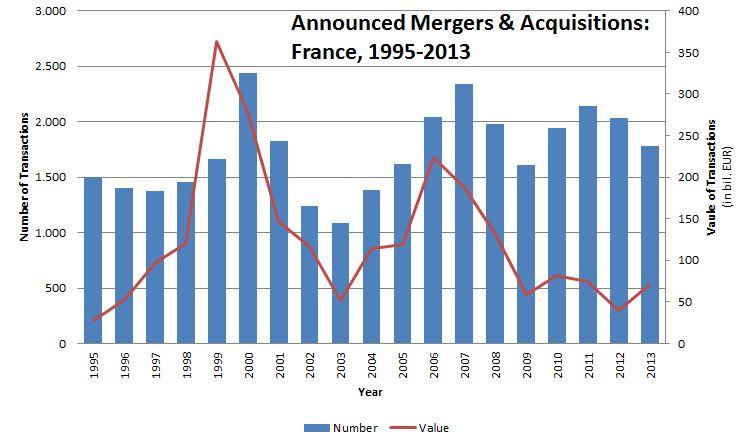

France is a founding member of the EU. An analysis of its M&A activities between 1995 and 2013 shows that the highest M&A transactions occurred in 2000 (2,500 M&A deals, valued at £345 billion) (see appendix one). The lowest number of M&A transactions (within the same period) occurred in 2003 when the country posted about 1,100 M&A transactions with a total value of about £150 billion (Institute of Mergers, Acquisitions, and Alliances 2013).

Germany

Germany is a founding member of the EU. However, an assessment of M&A transactions between 1991 and 2013 shows that the numbers and values of M&A transactions in Germany have been unstable. Since 1991, the numbers of M&A transactions have increased, until 2000 when the volume of transactions significantly dropped from about 3,100 transactions (valued at about £520 billion) to 2,100 transactions in 2001 (valued at about £350 billion) (Institute of Mergers, Acquisitions, and Alliances 2013). In 2003, Germany reported the greatest drop in M&A values (1,600 transactions). In 2013, Germany reported slightly more than 1,500 transactions valued at close to £300 billion (Institute of Mergers, Acquisitions, and Alliances 2013).

Greece

Greece joined the EU in 1981. The country reported about 88 mergers and 38 acquisitions between 1987 and 1989 (Katsos & Lekakis 1991). In 2006, the value of M&A activities reached £9.6 billion. The value of M&A transactions increased in the first half of 2007 because Kelemenis & Lazaridou-Elmaloglou (2008) report that about £5.5 billion worth of M&A transactions occurred during this period. No significant M&A transactions occurred in the last half of 2007, but in the first half of 2008, big deals occurred (worth about £5.3 billion) (Kelemenis & Lazaridou-Elmaloglou 2008). ZEW (2012) says, between 2009 and 2011, the number of M&A transactions have decreased by about 73%.

Hungary

Hungary joined the EU in 2004. An analysis of the country’s volumes of M&A transactions shows a declining trend. For example, the numbers of M&A transactions have steadily declined from 189 in 2009 to 102 in 2012 (CMS 2014). However, the values of M&A transactions have greatly varied. For example, CMS (2014) says Hungary reported £3,536 million worth of M&A deals in 2009, £1,532 million worth of M&A deals in 2010, £3,933 million worth of M&A deals in 2011, and £729 million worth of M&A deals in 2012.

Italy

Italy is among the founding members of the EU. However, an analysis of M&A transactions between 1991 and 2013 shows an unstable trend in the value and numbers of M&A transactions. Since 1991, the country has witnessed a significant increase in the number of M&A transactions (from about 680 transactions, in 1991, to about 1,150 transactions in 2000) (Institute of Mergers, Acquisitions, and Alliances 2013). There was a significant drop in the number of M&A transactions in 2001 and 2002, but, thereafter, the numbers increased from about 700 transactions in 2003 to about 900 transactions in 2008. The country reported the highest value of M&A transactions in 2008, valued at about £250 billion. In 2013, the country reported about 600 M&A transactions, valued at about £130 billion (Institute of Mergers, Acquisitions, and Alliances 2013).

Latvia

Like Estonia, Latvia joined the EU in 2004. Saikevicius (2013) said, since joining the EU, the country has reported three M&A transactions (up to 2011). The Raila Legins & Norcous Firm (2012) says the country’s top five M&A transactions, within this period, amounted to £52 million.

Lithuania

Saikevicius (2013) said, since joining the EU, Lithuania has reported 101 M&A transactions (up to 2011). Baltic Business News (2014) also says 15 transactions were worth more than £4 million (in 2012), while in 2013, 20 transactions were worth more than £4 million.

Luxembourg

Luxembourg is a founding member of the EU. An assessment of the country’s M&A transactions between 2004 and 2011 shows that the country reported 85, 98, 131, 292, 166, 85, and 24 transactions in 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, and the first two quarters of 2011 respectively (Merger Market 2011). The values of these mergers were £49 billion, £55 billion, £80 billion, £170 billion, £87 billion, £45 billion, £42 billion, and £12 billion (in the same order) (Merger Market 2011). The Global Finance (2014c) says the values of M&A transactions (cross-border) in 2008, 2009, 2010, and 2011 were £5,913 million, £2,466 million, £314 million, and £-15,132 million respectively.

Malta

Malta joined the EU in 2004. Saikevicius (2013) said, since joining the EU, Malta has reported 12 M&A transactions (up to 2011). The Global Finance (2014b) says, in 2008, 2009, 2010, and 2011, the values of M&A transactions (cross-border) were £18.24 million, £0, £171.42 million, and £9.48 million respectively.

Netherlands

Netherlands is a founding member of the EU. An assessment of the country’s M&A transactions, since 1991, shows that Netherlands reported the highest M&A activities in the mid-2000s. The country’s highest value of M&A activities occurred in 2000 when the total value of M&A transactions reached £297 billion. This value represented about 1,190 M&A transactions. However, since 2008, the values and numbers of M&A transactions have been decreasing. For example, the Institute of Mergers, Acquisitions, and Alliances (2013) explain that the numbers of M&A transactions have decreased from about 1,150, in 2008, to about 680 transactions, in 2013. This drop has translated to a similar decline in the values of M&A transactions from about £290 billion, in 2008, to about £175 billion, in 2013 (Institute of Mergers, Acquisitions, and Alliances 2013).

Poland

Poland joined the EU in 2004. Since then, the numbers of M&A activities have been on a steady growth. For example, after the country joined the EU in 2004, the number of M&A transactions increased from about 120 transactions in 2004 to about 220 transactions in 2005. This trend has characterized the number of M&A transactions up to 2010 when the volumes and numbers of M&A transactions reached 510 and £15 billion respectively. Since 2010, these figures have significantly declined to about 304 and £9.1 billion, respectively (Institute of Mergers, Acquisitions, and Alliances 2013).

Portugal

An assessment of Portugal’s M&A deals between 2000 and 2005 shows that Portugal reported seven significant M&A deals that amounted to about £602 million (Boubakri & Cosset 2011). Out of the seven deals, five were cross-border (valued at about £254 million) (Boubakri & Cosset 2011). The Global Finance (2014d) says the values of cross-border M&A transactions that occurred in 2008, 2009, 2010, and 2011 were £848 million, £900 million, £6,534 million, and £1752 million respectively.

Republic of Ireland

Ireland joined the EU in 1973. However, a statistical analysis of its recent M&A transactions, since 2006, shows that the total value of M&A deals in 2006 was about £20 billion. The years 2011 and 2013 have reported the highest values and numbers of M&A transactions because the Merger Market (2013a) reports that in 2011, the value of M&A transactions has been about £25 billion. Within the same year, the Merger Market (2013a) also reported that the number of M&A transactions amounted to about 120 deals. In 2013, the value of M&A transactions has been about £80 billion. The highest number of M&A transactions, within this year, occurred in the first quarter of 2013 when Merger Market (2013a) reported about 122 transactions.

Romania

Romania joined the EU in 2007. CMS (2014) says the values of M&A transactions have been declining since 2009. For example, between 2009 and 2010, Romania reported a significant decline in the value of M&A transactions from £2,363 million to £1,688 million (CMS 2014). There was a further decline in the value of M&A transactions between 2010 and 2011 because CMS (2014) says the value of M&A transactions further declined to £1,264 million in 2011. However, in 2012, there was a slight increase in M&A values because this figure increased to £1,464 million (CMS 2014). The total volume of M&A transactions does not follow the same pattern because between 2009 and 2010, the number of M&A transactions increased from 189 to 223 (CMS 2014). However, from 2010 to 2012, the volumes declined from 223 transactions (in 2010) to 118 transactions in 2012 (CMS 2014).

Slovakia

Slovakia joined the EU in 2004. However, an assessment of the country’s volumes and values of M&A transactions, from 2009, shows a relatively steady number of M&A transactions. For example, between 2009 and 2011, the country reported 44, 48, and 46 transactions in 2009, 2010, and 2011 respectively (CMS 2014). There was a marginal decline in the number of M&A transactions in 2012 because CMS (2014) says there were only 38 transactions reported. As the volume of M&A transactions, the value of M&A transactions was relatively steady between 2009 and 2011. CMS (2014) said in 2009, 2010, and 2011, Slovakia reported £286 million, £290 million, and £235 million transactions respectively. There was an increase in the value of M&A transactions in 2012 because CMS (2014) says the value of M&A transactions within this period was £2,767 million.

Slovenia

Like Slovakia, Slovenia also joined the EU in 2004. However, unlike Slovakia’s steady M&A values, Slovenia reported a significant decline in M&A values in 2009, 2010, and 2011 (CMS 2014). The M&A values for the three years were £532 million, £380 million, and £187 million respectively (CMS 2014). The value of M&A transactions in 2012 was £376 million (CMS 2014). The numbers of M&A transactions within the four years of analysis were 48, 32, 42, and 34 in 2009, 2010, 2011, and 2012 respectively (see appendix three) (CMS 2014).

Spain

Spain joined the EU in 1986. However, between 1991 and 2013, Spain’s M&A transactions have not been lower than 200 (Institute of Mergers, Acquisitions, and Alliances 2013). The highest M&A transactions occurred in 2007 and 2008 when the country reported more than 1,200 and 1,550 M&A transactions respectively (valued at about £170 billion and £220 billion respectively). Since 2008, the volumes and values of M&A transactions in Spain have steadily declined to about 800 transactions in 2013 (during the same year, the country also reported a total value of M&A transactions of about £110 billion) (Institute of Mergers, Acquisitions, and Alliances 2013).

Sweden

Sweden joined the EU in 1995. Since joining the EU, the Scandinavian country reported the highest level of M&A transactions in 2007 and 2011 (Institute of Mergers, Acquisitions, and Alliances 2013). For example, in 2007, the country reported more than 1,400 M&A deals, valued at about £80 billion. The lowest M&A transactions occurred in 1997 when the country reported about 400 M&A transactions, valued at about £23 billion. Since 2011, the country’s volumes and values of M&A transactions have steadily declined from about 1,190 transactions, in 2011, to about 900 transactions, in 2013 (this decline also informs the decrease in the value of M&A transactions, from about £65 billion to £50 billion within the same period) (Institute of Mergers, Acquisitions, and Alliances 2013).

UK

The UK accounts for about one-quarter of all mergers and acquisitions that involve European companies (EIRO 2010). The number of M&A transactions has been on an upward trajectory from 1988 to 2000 (see appendix two). The year 2000 marked the highest number of M&A transactions because the UK announced about 5,200 M&A transactions (these deals were valued at about £845 billion). The second highest value of M&A deals occurred in 2007 when the country reported 5000 M&A transactions valued at about £845 billion (Institute of Mergers, Acquisitions, and Alliances 2013). Since 2008, the value of M&A transactions has decreased to about 2,900 transactions, in 2013, valued at about £480 billion (Institute of Mergers, Acquisitions, and Alliances 2013).

Which Sectors Have Engaged in the Highest and Lowest M&A Activities?

In the past three decades, M&A activities within the EU have affected the growth of different sectors, in different ways. An analysis of M&A activities among the EU-15 countries (EU member countries before April 2004), between 1995 and 2001, shows that M&A activities concentrated mainly in the service sector (Europa 2001). The banking, healthcare, defense, and technology sub-sectors reported the highest M&A transactions in this sector (Campa & Moschieri 2008). The graph below shows the spread of M&A activities at a community level.

As shown above, there was a significant increase in M&A activities in the EU from 1997 to 2000. Between 1991 and 1996, the value of M&A transactions did not increase significantly (£22.8 billion to £29.6 billion) (Palmieri 2002). Thereafter, the value of M&A transactions increased to £547.9 billion, in 1999. Although the numbers of M&A activities increased in 2000, as shown above, their values decreased during the same period. Different states posted different results in this regard. The graph below shows a breakdown of the performance of EU member states

According to the above graph, individual countries in the EU posted different M&A patterns between 1991 and 2001. For example, the sampled countries posted different levels of regional, community, and international M&A transactions. The European average of M&A transactions was 54.4% (Palmieri 2002). Only Greece surpassed this level by exceeding the European average of internal M&A transactions at 67.9% (Palmieri 2002). Luxembourg, Belgium, Ireland, Netherlands, and Denmark posted the highest levels of intra-community M&A transactions at 62.2%, 47.3%, 41.7%, 41.2%, and 35.7% respectively. Ireland, Netherlands, and Luxembourg had the highest international M&A transactions (Palmieri 2002).

Mergers in the Telecommunications Industry

Overview of the European Telecommunications sector

The 1990s heralded a new period of structural changes in the European telecommunications industry. This period marked the privatization of state-owned telecommunication firms and the end of monopolies (European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions 2005). The adoption of new reforms in the 1990s paved the way for increased competition and the lowering of tariffs in the sector. These changes led to an increased performance of the sector. For example, in 2003, the turnover growth rate was 5.6% (for the EU-15 countries) (European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions 2005). In recent years 2005-2013 (and the expansion of the EU), new entrants have entered the telecommunications market through mergers and acquisitions. The O2-Telefonica and the Vodafone-Mannesmann mergers are some examples of this expansion.

Vodafone-Mannesmann Merger

Pre-Merger Analysis

The Vodafone-Mannesmann merger is among the biggest mergers in corporate history. Before the German and British companies merged, their share price performances were impressive. Hopper & Jackson (2006, p. 147) believe that Mannesmann’s share prices were significantly undervalued in the pre-merger period. However, between 1996 and 2000, the company’s share price increased ninefold (€34 – €300) (Hopner & Jackson 2006). Vodafone also posted impressive share prices during the same period. Indeed, between 1996 and 2000, the company’s share price increased sevenfold (49 pounds – 343 pounds) (Hopner & Jackson 2006). Mannesmann’s price-book ratio also affirmed the company’s positive financial performance because, between 1992 and 1999, it increased from 1.4 to 10.2 (Hopner & Jackson 2006). Vodafone’s price-book ratio was higher than Mannesmann’s because, during the same period of analysis, its price book ratio increased from 7.7 to 125.5.

Mannesmann and Vodafone also had impressive company valuations before the merger because Mannesmann’s price-earnings ratio was 56.1, while Vodafone’s price-earnings ratio was 54.4 (Valuations at September 1999) (Hopner & Jackson 2006). The following table shows that although both companies had impressive company valuations, they posted different patterns of financial valuations.

According to the above statistics, Vodafone had a higher return on sales than Mannesmann did. However, Mannesmann was more profitable than Vodafone. This is because the company mainly traded in highly profitable markets. Nonetheless, because Vodafone had a higher market capitalization, analysts valued its stocks relatively higher than Mannesmann’s stocks.

Post-Merger Analysis

According to Vodafone’s company report, its stock prices decreased after the merger with Mannesmann. The following graph shows this decline

According to the above graph, Vodafone’s share prices decreased from 2000 to 2002. Thereafter, the share prices stabilized until 2006 when the company reported a marginal increment in the same. After the merger, Vodafone experienced a declining sales growth. In fact, between 2000 and 2005, the company’s sales growth declined from 134% to -21% (Higson 2009). The significant decline in sales numbers led to a similar decline in the company’s earnings. For example, between 2000 and 2005, the company’s earnings decreased from €487 million to €-9,015 million (Higson 2009).

The company’s shareholder dividends and earnings per share also registered the same trend because, before the merger, there was a consistent growth of these financial indices. However, after the merger, both indices decreased. Nonetheless, Vodafone’s financial ratios show that the dividends per share were relatively unchanged after the merger period. For example, in 2000, 2001, 2002, and 2003, the dividends per share were 1.3, 1.4, 1.5, and 1.7 respectively (Higson 2009). During the same period of analysis, the company’s financial statements showed a decline in stock returns. For example, in 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, and 2004, Vodafone’s stock returns were 52%, -44.2%, -32%, -12.2%, and -16.5% (Higson 2009). The Mannesmann merger mostly affected the company’s return on equity because the company’s financial records show that the return on equity decreased from 68.9% in 1999 to 0.3% in 2000 (during the merger period) (Higson 2009). In subsequent years, the return on equity was -6.7%, -11.5%, and -7.4% for the years 2001, 2002, and 2003 respectively (Higson 2009). Comprehensively, these financial indices show little value creation for Vodafone after the merger.

Market Power Theory

The market power theory explains the quest by companies, such as Vodafone, to increase their market share through mergers and acquisitions. An analysis of the above merger shows that Vodafone pursued this strategy to cement its position in the European market. The market power theory fits into Vodafone’s strategy because the company pursued a diversification strategy that hinged on geographic expansion and activity expansion. However, the positive financial growth reported by both firms does not necessarily stem from the increased market power of both entities (Hopner & Jackson 2006). For example, if an industry has four firms, in an ideal market, the four firms should share ¼ of the profits each. Similarly, if two firms exist in an industry, the firms should share ½ of the profits.

In the Vodafone and Mannesmann case, the merger between the two firms reduced the number of firms to three. This should mean that the firms should share 1/3 of the profitability. A keen analysis of the market power theory, here, shows that although the concentration of markets through these merger and acquisition transactions increases profitability, the increased sales would be insufficient to counter the price increments that would arise in such a market situation. Therefore, although merging firms may enjoy increased market power, the expected profitability should exceed the marginal costs incurred by both companies. The only exception would be if the merging firms expect to form a monopoly. Based on the assessment of Vodafone’s financial figures, it is critical to say that the increased market power of Vodafone (after the merger) also emerged in the company’s (relatively) stable financial performance after the merger. For example, after the merger, the company increased its dividend per share in 2000, 2001, 2002, and 2003, by 1.3, 1.4, 1.5, and 1.7 respectively (Higson 2009). These financial indices show that the merger was relatively successful.

O2-Telefonica Merger

Pre-Merger Analysis

Before merging with O2, Telefonica had a market share of about 145 customers (Offer Document 2005). The company’s market capitalization was about £41.2 billion (Offer Document 2005). The company’s 2004 financial reports showed that the company posted revenues of about €30.3 billion (Offer Document 2005). The same financial report showed that the company’s shareholder equity and EBITDA figures were €16.2 billion and €13.2 billion respectively (Offer Document 2005). A deeper analysis of Telefonica’s financial data shows a consistent financial performance for the three years before the merger with O2. For example, an analysis of the company’s shareholder equity shows that the company created adequate shareholder value in the three years before the merger (TSA 2013). Within this period, the company’s earnings per share increased from 0.62 to 1.304. This increase amounted to a 42.9% increase in earnings per share (TSA 2013, p. 44).

Before its merger with Telefonica, O2 had a market share of about 25.7 million customers (Offer Document 2005). Comparatively, before the merger with Telefonica, O2’s financial records affirmed the company’s financial agility before the merger. For example, the company’s revenue before the merger was about £6,683 annually million (Offer Document 2005). An analysis of the company’s 2005 financial report also shows that the EBITDA was £1,768 million (Offer Document 2005). The same company report shows that the company’s net assets were £10,281 million (see appendix 6) (Offer Document 2005)

Post-Merger Analysis

After Telefonica acquired O2, the company reported a favorable revenue growth because financial estimates (between 2009 and 2012) show that the company experienced average revenue growth of about £61,565 million after the merger (Business Week 2014). A deeper assessment of the company’s revenue figures shows a strong consistency in the company’s revenue margin. For example, since 2009, Telefonica has reported positive revenue figures of between £58,035 million, £61,474 million, £63,576 million, £63,178 million in 2009, 2010, 2011, and 2012 respectively (Business Week 2014). The company’s gross profit figures also followed the same pattern because, in 2009, 2010, 2011, and 2012, the company’s gross profit figures were £34,543 million, £36,117 million, £36,911 million, and £36,535 million respectively (Business Week 2014).

An analysis of Telefonica’s financial ratios also shows a favorable financial performance. For example, in 2009, the company’s current ratio was 0.88 (Morning Star 2014). In 2010 and 2011, this figure decreased to 0.63 and 0.64 respectively (Morning Star 2014). However, in 2012, this figure increased to 0.81 (Morning Star 2014). The quick and cash ratios follow the same pattern because the financial figures of both estimates were highest in 2009 and 2012. The highest quick ratios were 0.85, in 2009, and 0.74 in 2012 (Morning Star 2014). A comprehensive analysis of these financial ratios shows that the company’s financial performance was relatively stable after the merger.

Market Power and Synergy Theories

As shown from the above financial analysis, Telefonica increased its revenues after merging with O2. Estimates show that the company’s revenue growth amounted to about £61,565 million annually (Business Week 2014). A closer look at these figures shows that Telefonica enjoyed increased revenue synergies for almost four years after the merger (ending 2012). The improvement of these synergies shows that such mergers improve the operational performance and shareholder values of their companies (albeit dismally). However, owing to the dynamics surrounding the Telefonica-O2 merger, we see that the motivation to expand markets emerged as a greater motivator for entering into the merger (than cost or revenue advantages/synergies) (Offer Document 2005).

This fact draws our attention to the role of the market power theory in explaining this merger and its relative success. According to the impressive financial ratios and profitability figures of the Spanish telecommunications company, it is important to say that Telefonica already enjoyed a favorable financial position, before the merger. Therefore, the main motivation for merging with O2 was not to improve the company’s profitability or shareholder value (at least in the short term). Instead, the company wanted to increase its market presence in Europe by venturing into the British market. This analysis, therefore, shows that the market power theory is more relevant in explaining this merger.

Mergers and Acquisitions in the Automotive Industry

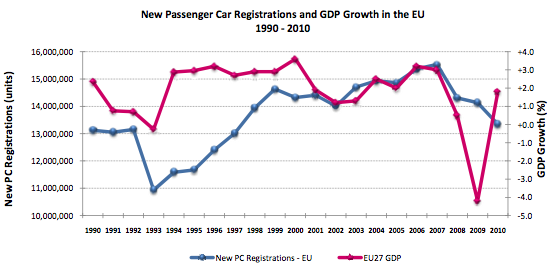

The EU automotive industry has grown in the past 20 years. The graph below shows that the volume of new car registrations has followed the pattern of GDP growth in the EU. It also shows a small slump in new car registrations between the 1992/1993 periods. However, from 1994 to 2007 (the period of analysis for this section of the paper), the volume of new car registrations has significantly increased

A deeper analysis of the EU automotive industry appears in this section of the paper. This analysis relates to the performance of the 1994 BMW-Rover merger in this industry.

BMW-Rover Group Merger

Pre-Merger Analysis

Today, BMW enjoys a positive brand image for its superior and high-quality car brands. However, towards the turn of the decade, the company experienced bad economic fortunes when it merged with the British automotive firm, Rover Group, in a £1.7 billion deal (Dhar 2013). Contrary to the expectations of BMW’s management, the merger did not meet their expectations. An assessment of BMW’s financial position before the merger shows a positive financial performance. For example, in 1990, 1991, and 1992 BMW reported sales increments of 2.5%, 9.8%, 4.7% respectively (see appendix four) (BMW Group 1999).

The company’s cash flow, as a percentage of investments, also showed the same pattern because, in 1990, 1991, 1992, 1993, and 1994, the increases in cash flow were 134.6%, 133.3%, 145.8%, 115.9%, and 100.7% (respectively) (BMW Group 1999). The shareholders’ equity, as a percentage of fixed assets, was also positive because 1990, 1991, 1992, 1993, and 1994 figures were 87.4%, 94.7%, 98.3%, 98.2%, and 67.4% respectively (BMW Group 1999). Finally, the debt to equity ratio also posted the same positive returns because an analysis of 1990, 1991, 1992, 1993, and 1994 figures shows that the debt to equity ratios of financial services was 12.7%, 12.8%, 13.0%, 12.0% and 12.2% respectively (BMW Group 1999).

Post-Merger Analysis

After the merger with Rover group, BMW started to make significant financial losses. For example, in 1999, BMW made losses of about DM -2 billion (Adari, Thrane & Taube 2004). An assessment of BMW’s 1999 financial report shows that 1999 losses for the Rover group were up by 26.1% (€-250 million to €-1,207 million) (BMW Group 1999). The company’s sales figures also reported the same negative outlook because Adari et al. (2004) say the company’s sales plummeted by up to 32%. Particularly, the fact that Land Rover’s sales were declining in Britain worried many of BMW’s managers (especially because Rover was a British brand). Part of the dwindling sales numbers stemmed from currency fluctuations because when BMW acquired Rover (in 1994), the rate was DM2.48, but in 1999, the rate was 2.97 (Adari et al. 2004).

This currency fluctuation meant that BMW made losses of about DM5.94 for every unit sold (Adari et al. 2004). It was difficult to compensate for such losses through other financial means. The dwindling financial fortunes of BMW further affected the company’s share prices because between 1997 and 1999, the company lost up to 20% of its share value (Adari et al. 2004). While BMW made these losses, it continued to invest more money in the Rover Group, thereby deepening its financial problems. For example, between 1994 and 1999, BMW increased its investments from DM 0.9 billion to DM 1.4 billion (Adari et al. 2004). According to BMW’s 1999 financial report, the declining market for Rover models reduced the company’s automobile production by 5% (BMW Group 1999). Rover’s small market share reduced BMW’s production volumes to 1,147,400 units (BMW Group 1999). According to the graph below, we see that Rover brands accounted for the greatest decline (-32%) among all BMW subsidiaries

An independent analysis of Rover’s market share shows that it significantly dropped after the merger. A broader assessment of the EU automotive market shows that the car market was expanding during and after the merger period (European Automotive Manufacturers Association 2011). This fact stems from the number of new car registrations that occurred between 1993 and 1997 (see figure 10) (European Automotive Manufacturers Association 2011). By focusing our analysis on new car registrations in the EU (between 1993 and 1999), it is pertinent to mention that the declining market share of the Rover group occurred during the expansion of the European car market. Therefore, the decrease of the Rover market share was isolated. Indeed, the following graph shows that the company’s market share significantly declined from 11.3% in 1994 to 4.6% in 1999.

Relative to the above figure, it is pertinent to understand that before BMW bought the Rover Group, in 1994, its European market share was about 12% (David-Morrison Organisation 2000). However, after purchasing the Rover Group, its market share declined to 5% (David-Morrison Organisation 2000). Combined with Rover Group, BMW’s market share was 6.4%, in Europe (Hothi 2005, p. 91). A comparison of Rover and BMW’s market share (in Europe) after the merger shows that Volkswagen, General Motors, PSA, Ford, Fiat, and Renault had a greater market share of 16.5%, 13%, 12.2%, 12.2%, 11.1, and 10.5% respectively (Hothi 2005). The only companies that had lower market shares were Nissan, Mercedes-Benz, Toyota, and Mazda, at 3.5%, 3.1%, 2.8%, and 1.7% respectively (Hothi 2005).

Although BMW made significant financial losses from the market decline of Rover’s brands, other BMW subsidiaries performed well. The positive performance of the BMW subsidiaries informs the relatively stable share prices of ordinary and preference share prices in the post-merger period as shown below

Although BMW’s subsidiaries helped to support the company’s financial position, the continued losses made by the Rover subsidiary made it untenable for the company to maintain the acquisition as a BMW subsidiary. BMW later sold it off.

Free Cash Flow Theory

The free cash flow theory explains BMW’s acquisition of the Rover group because it shows how managers use excess cash to expand businesses, as opposed to issuing shareholder dividends. This theory applies to the BMW-Rover acquisition because, before acquiring the Rover group, BMW enjoyed a positive cash flow and increased profitability (at least four years before the acquisition) (BMW Group 1999). Certainly, an analysis of the company’s cash flow in the pre-merger analysis showed that the company’s cash flows in 1990, 1991, 1992, 1993, and 1994, increased by 134.6%, 133.3%, 145.8%, 115.9%, and 100.7% (respectively) (BMW Group 1999). Based on the positive cash flow, BMW’s managers decided to invest its excess money by acquiring the Rover Group.

According to the free cash flow theory, managers pursue this option to increase their control and expand their business presence. Hothi (2005) explains that the motives of BMW’s managers fit this description because they wanted to include the highly profitable Land Rover division of the Rover group into the BMW product array. Moreover, the market expansion into Britain was a huge motivator for BMW’s manager’s to acquire the Rover Group because the subsidiary’s main market share was in Britain (moreover, Rover Group was a British brand). Comprehensively, the free cash flow theory explains this acquisition because it informs the decision of BMW’s managers to expand its business portfolios by acquiring the Rover Group, as opposed to using its excess cash to issue dividends to shareholders.

Mergers in the Chemical Industry

The European chemical industry is among the biggest industrial sectors in Europe. Since 1991, the industry has witnessed increased sales. For example, in 1991, 1995, 1999, 2003, 2007, and 2011, the EU chemical industry has reported sales of €295 billion, €331 billion, €365 billion, €413 billion, €524 billion, and €539 billion respectively (CEFIC 2012). However, within the same period, the global market share of the EU chemical industry has decreased from 36% to 20% (CEFIC 2012). Nonetheless, the industry has witnessed increased M&A activities, such as the AkzoNobel–Imperial Chemicals Industries merger

AkzoNobel–Imperial Chemicals Industries plc. Merger

Pre-Merger Analysis

Before the merger with AkzoNobel, ICI’s financial records showed positive company growth for the four years before the merger (Imperial Chemical Industries 2013). For example, the company’s performance before the 2008 merger shows decreased turnover figures (eight years before the merger) (Imperial Chemical Industries 2013). For example, between 2000 and 2005, the company’s turnover reduced from £7,748 million to £5,812 million (Imperial Chemical Industries 2013). ICI’s profitability was relatively steady before the merger. In fact, between 2000 and 2005, the company reported increased profitability in most of its key business segments. Furthermore, in 2002, the company reported more profits, of about £317,000,000 (this figure increased to about £500,000,000 in 2005) (Imperial Chemical Industries 2013).

An assessment of AkzoNobel’s profitability, from 2001 to 2007, shows that the company never reported any losses (see appendix five) (ANC 2011, p. 170). Within the same period, the company reported the highest profits in 2004 and 2005 when it made £981,000,000 and £998,000,000 respectively (ANC 2011, p. 170). The company’s financial ratios show that AkzoNobel’s dividend per share was constant for six years 1.2 (before the merger) (ANC 2011). Overall, these figures show that AkzoNobel’s performance was impressive before the merger.

Post-Merger Analysis

The merger between AkzoNobel and ICI brought significant improvements to AkzoNobel’s company profile. For example, it increased the company’s global market share from 14% to 16% (Koster & Noordhuis 2009). This improvement mainly stemmed from the increased dominance of the company in the decorative paint market (Koster & Noordhuis 2009). After the merger with ICI, AkzoNobel maintained a relatively flat dividend per share (ANC 2011). The average dividend yield for the first two years was 1.8 (ANC 2011). In 2008, the company’s cash flow was significantly low because of the acquisition payout to ICI.

However, in 2009, the company recorded a profit of £330 million (ANC 2011). The company’s profitability (for continuing operations) for the first three years after the merger shows a positive cash flow (ANC 2011). The company’s balance sheet shows that after the merger, AkzoNobel had the revenue to invested ratios of 1.07 and 1.11 for 2008 and 2009 respectively (ANC 2011, p. 171). Similarly, the equity/non-current asset ratios were 0.64 and 0.65 for the same period (ANC 2011, p. 171). These financial indices show a positive financial performance after the merger. The free cash flow theory and the agency theory explain this performance further

Free Cash Flow Theory and the Agency Theory

As mentioned in this paper, the free cash flow theory predicts that most managers would spend their money pursuing mergers and acquisitions that improve a company’s growth and expansion goals. This motive clashes with shareholder goals of making a profit (dividends) from company activities. This theory widely explains the AkzoNobel and ICI merger because AkzoNobel acquired ICI for its potential to increase the company’s growth and dominance in the market. In 2008, AkzoNobel’s financial records showed a very low cash flow (from the acquisition) (ANC 2011). This poor financial performance mirrors the framework of the free cash flow theory, which predicts that acquiring companies could suffer from low net present values when they acquire new companies. Stated differently, the theory predicts lower total gains from acquiring companies. Although this strategy harmed AkzoNobel’s financial reports (in the short-term), it paid off in the end because an analysis of the company’s books, five years after the merger, shows that the company significantly increased its financial position (ANC 2011).

The decision by AkzoNobel to pursue the negative net-present value strategy exists from an understanding of how the agency and the free cash flow theories explain mergers and acquisitions. Both theories say managers prefer to pursue corporate strategies that do not benefit shareholders in the short-term because they want to devalue their company stocks to reduce shareholder expectations on their investments. Therefore, like AkzoNobel, which had a highly valued stock price before the merger (high ROI and profitability figures); companies that suffer from exceptionally high expectations on their stock prices are likely to pursue strategies that devalue their stock, at least in the short-term. This model largely explains why AkzoNobel’s cash flow was relatively low during the first few years after the merger.

Conclusion

The purpose of this paper was to establish the effects of mergers and acquisitions on the operating performance and shareholder wealth of EU firms. To answer the research question, this paper explained the global trend in M&A activities and the numbers and values of M&A activities in the EU. From the expansion of the global economy, mergers and acquisitions have emerged as important corporate development processes. The increased concentration of capital and the expansion of company presence in new markets underlie the importance of M&A transactions, globally. The increased numbers of regional and global M&A activities stemmed from the expansion of global economies and market liberalization (through globalization). These developments have eased the process of business expansion (from national markets to international markets). Since M&A activities keep changing, they will continue to be an important feature of the global business space.

Because of the importance of M&A activities in the corporate world, this paper used the synergy, market power, free cash flow, and agency theories to explain why M&A activities occur (plus their potential ramifications for companies). The market power and free cash flow theories explained why companies engage in such transactions. Comparatively, the agency theory explained the modalities of such engagement, while the synergy theory explained the ramifications for engaging in such transactions. By combining these theories and adopting the accounting technique, this paper used the secondary data collection technique to obtain financial information regarding four EU firms. This analysis occurred as a quantitative study because the paper used financial measurements, such as profitability, ROI, ROE, and similar financial indices to answer the research question.

After weighing the findings of this study, it is critical to understand that all the companies sampled in the paper reported positive and negative financial indices before and after the merger. Since it would be misleading to analyze the study based on an individual analysis of these indices (purely), it is important to understand the broader analysis of the overall performance of the sampled EU companies. Particularly, this focus shows that although many mergers may report improved financial numbers, such numbers do not necessarily translate to increased shareholder values. Based on the financial figures reported by the sampled companies, it is crucial to say that most of the financial gains reported by the takeover companies are not “highly significant” to the shareholders.

The relatively improved ROI and ROE figures depicted in some of the above case studies show that the shareholders do not necessarily experience increased value for their investments. Indeed, these figures do not increase significantly. In fact, in some circumstances, such as the BMW-Rover case, ROI and ROE figures decrease significantly after the mergers. Another example is the Vodafone-Mannesmann merger because although Vodafone posted favorable revenue growths, it did not post a favorable financial performance after the merger with Mannesmann. Particularly, the company performed poorly, in terms of the net and gross profits. Similarly, the company’s current, quick, and activity ratios report the same story. Nonetheless, evidence from this paper shows that this phenomenon should be expected because acquiring companies often realize decreased profitability after mergers. Certainly, it is crucial to point out that Vodafone’s financial performance before the merger was more impressive than its performance after the merger. This analysis shows that the merger did not increase the company’s operating performance or shareholder wealth.

Although the financial performance of the above companies may be mixed, the focus on understanding if mergers and acquisitions create shareholder wealth draws attention to the share returns of the companies sampled. Using this focus of analysis, the findings of this paper show that the shareholders of the target company gain from mergers and acquisitions because they receive acquisition revenues from mergers and acquisitions. Similarly, evidence from this paper shows that the share prices of the target companies often appreciate significantly during merger negotiations (such as the Vodafone-Mannesmann merger and AkzoNobel–Imperial Chemicals Industries merger). Therefore, when competitors acquire such companies, the shareholders of the target companies profit significantly from overpriced shares. This analogy is true for the O2-Telefonica merger and the Vodafone-Mannesmann mergers (particularly, the share price for Mannesmann significantly increased before the acquisition).