Abstract

Fredric Jameson’s postmodernism theory is considered to be “the effort to take the temperature of the age without instruments and in a situation in which we are not even sure there is so consistent thing as an ‘age,’ or ‘zeitgeist’ or ‘system’ or ‘current situation’ any longer,” it is supposed that the shift from modernism to postmodernism transpired from urban planning and architecture to various stylistic features of arts, literature, theater, film, music, dance, and painting, to MTV, CNN, and the internet. Cyberspace and part-human and part-robot fantasies are believed to be just as postmodern as the threat of nuclear and ecological self-destruction, globalization and deregulation, or the morbid projections of generation X. Given the plurality of interpretations, it is hardly surprising that “postmodernism” is often accused of being an illogical catchphrase. Above anything else, it has provoked highly opposing descriptions of its political goals, cultural functions, historical materialization, punitive location, and geopolitical realm.

By way of examining the most pertinent theories of postmodernism (Irving Howe, Susan Sontag, Leslie Fiedler, Fredric Jameson, Ihab Hassan, François Lyotard, Jürgen Habermas, Andreas Huyssen), this paper brings to light an understanding of whether the term designates a certain aesthetic strategy, a historical period, or a particular way of thinking most prominently associated with modernism, pluralism and deconstruction.

Introduction

Postmodernism is a style applied in architecture, arts, literature, and criticism established in active response to modernism, about other periods or styles in an excessively concerned way and a rejection of the idea of high art.

At the dawn of the 1980s and 1990s, the leading modification of postmodernism adapted traditional architectural details and styles in entirely original compositions, without the awkwardness and oddities of ironic postmodernism. Stern called this variant creative postmodernism or modern traditionalism. Venturi, Moore, and Graves all moved in this direction, joining other architects such as Graham Gund, Thomas Beeby, and Stern. A representative example of this design approach is Stern’s Observatory Hill Dining Hall (1982-1984) at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. The dining hall combines red brick, white wood trim, and Tuscan Doric columns, referring to the adjoining buildings by Thomas Jefferson, but employs modern building forms and walls with large windows (Encarta, 2007).

Differences between modernism and postmodernism

Modernism flourished between the 1650 and 1950s. Empiricism and epistemological are the two dominant approaches in gaining knowledge. Empiricism, knowing through the senses, gradually evolved into scientific empiricism of modern science with the development of modernist methodology. While epistemological approach uses reasoning or logic. “Modernism is an experiment in searching the veracity of a situation. It can be characterized by self-consciousness and reflexiveness. This is very closely related to Postmodernism (Sarup 1993).”

Frank Lloyd Wright, an American architect, wrote in 1910 that the modern building would be ‘an organic entity…as distinguished with that former insensate combination of parts…one great thing instead of a quarreling collection of so many little things.’ Similarly, Walter Gropius insisted that the modern building must be true to itself, logically transparent and virginal of lies on trivialities’ The prophets of modern architecture insisted time and again on the unity of the building, as the organic express of an inner principle, rather than the external imposition of from…Le Corbusier praised Michelangelo’s Capitol in Rome for the way that it heaps itself together, in unity, expresses the same law throughout, and wrote that a building was like a bubble which is perfect and harmonious if the breath has been evenly distributed and regulated from the inside. The exterior is the result of an interior.

Postmodernism occurs from the 1950s up to our present time. Postmodernism existed due to the insufficiency of the modern approaches to knowing, postmodernists support epistemological pluralism which makes use of multiple ways of knowing – scientifically and logically.

Ryan Bishop defines postmodernism in a brief article from Encyclopedia of Cultural Anthropology (1996) as a diverse movement, originating in aesthetics, architecture, and philosophy. “Postmodernism embraces a systematic skepticism of grounded theoretical perspectives. Applied to anthropology, this skepticism has shifted focus from the observation of a particular society to the observation of the (anthropological) observer.”

Postmodernity mainly focuses on the tensions of distinction and similarity erupting from processes of globalization: the accelerating circulation of people, the increasingly dense and frequent cross-cultural interactions, and the unavoidable intersections of local and global knowledge. “Postmodernists are suspicious of authoritative definitions and singular narratives of any trajectory of events.” (Bishop 1996: 993). Post-modern attacks on ethnography are based on the belief that there is no true objectivity. The authentic implementation of the scientific method is impossible.

“Postmodernism has meant a renewed awareness of the suppressed linguistic or connotative dimension in architecture”

It is not difficult to imagine how these “progressive and conventional” categories could be applied to a series of examples of orthodox modern architecture in defense of a theory of “simplicity and consistency” in architecture. However, it is also apparent that these categories could be listed with the provision that each of the different kinds of anticipation should not be fulfilled. In Man’s Rage for Chaos, Morse Peckham gives a distinctive list of categories with the provision that the anticipation should not be fulfilled and calls them “discontinuities”. In Peckham’s theory, “discontinuities” are a defining characteristic of art.

Robert Venturi, author of Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (Museum of Modern Art, 1966), is one of the most noted architects of the Philadelphia school and Professor of Architecture at Yale. Though he completed only a few commissions, his ideas have been extremely influential and his projects widely published.

He writes: I prefer ‘both-and to ‘either-or,’ black and white, and sometimes gray, to black or white. A reasonable architecture arouses various levels of meaning and combinations of focus; its space and its elements become readable and workable in several ways at once. (p. 23.)

He sees “orthodox modern architecture” as illustrated by “either-or,” where, for example, a support is seldom an enclosure. The examples that he presents of both-and-in architecture include the ceilings of Sir John Soane’s secular chambers which are “both rectangular and curvilinear, and domed and vaulted.” (p. 36.) Also referred to is pre-cast concrete construction which can be continuous yet fragmentary, flowing in profile yet surfaced with joints.” (pp. 36-37.)

“The most obvious and frequently remarked – on form of pluralism in postmodernist architecture is its openness to the past”

The last quarter of the 1970s reinforced a recent trend in architecture toward pluralism of styles. Modernism does not dominate anymore, in the sense of high-technology, smooth-skin, metal-and-glass geometric formalism. Previous extensive retort against historical styles, regional forms, and traditional materials has now changed to enthusiasm for them. There is a renewed interest in local character, in richer artistic experiences, and a greater diversity of materials, colors, patterns, textures, and methods of construction, although some of the more conservative architects condemn this trend.

American architecture at the beginning of the 21st century has avoided the single-style sterility that International Style modernism threatened to impose. Instead, it remains open to a myriad of design approaches, suitable to a wide variety of locations, functions, and symbolic messages.

Deconstructivism

In theory and early designs, deconstruction included the dismantling of architectural elements and the reorganization of their constituent parts. In these designs, architects did not concern themselves with the physical laws of the real world, and most of their early proposals were impossible to be built. Later on, actual buildings came into being from some of these ideas, and the architects had to address the realities of construction and the weight of materials. The resulting buildings were typically disjointed in form, and they dramatically contradicted standard conventions of design and construction.

Architect Frank Gehry has enjoyed the playfulness deconstructivism allows. Gehry’s designs vary from a kind of ascetic modernism in the early 1970s to increasingly asymmetrical compositions in the late 1980s and 1990s, with colliding angular forms and other unusual juxtapositions. As the geometries of his buildings became more intricate and he introduced compound curves, Gehry and his staff depend increasingly on computer-aided design, adapting software developed in France for aircraft design.

The intriguing forms of Gehry’s architecture attracted worldwide attention, and he received a commission for the Vitra International furniture assembly plant and museum (1987-1989) in Weil am Rhine, Germany. The museum portion of the building provides a good example of Gehry’s use of curving and intersecting volumes and spaces. A second facility for Vitra (1988-1894) near Basel, Switzerland, also incorporates curving forms, with portions covered in sheets of zinc metal.

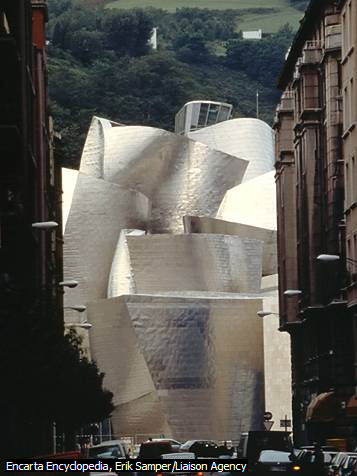

Gehry’s approach transpired in his striking design for a branch of the Guggenheim Museum (1991-1997) in Bilbao, Spain. The computer became an essential part of the design and construction process by simultaneously solving design problems, developing construction details, working out structural technologies, and keeping track of building costs. Rare titanium metal came on the market as the Russian government sold its titanium reserves to raise urgently needed finances. As a result, Gehry could purchase this costly metal and have it fashioned into thin sheets to cover the curving surfaces of the Bilbao Guggenheim. The lightweight and reflective titanium surface accentuate the building’s sculptural masses, which shimmer in sunlight (Encarta, 2007).

Images

Pablo Sanchez/REUTERS

Designed by American architect Frank Gehry, the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao opened in 1997 in Bilbao, a city in northern Spain. The building’s curvaceous form is made even more unusual by the rippling reflections on its titanium surface.

Erik Samper/Liaison Agency

The Guggenheim Museum Bilbao opened in the Basque city of Bilbao, Spain, in October 1997. Located on the city’s waterfront, the modern art museum offers a dramatic contrast to Bilbao’s industrial setting.

SuperStock

Designed by German-American architect Helmut Jahn, the United Airlines Terminal in Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport opened in 1987. Flashing lights above and curving colored glass to each side provide a stimulating visual environment for airline passengers as they move between the terminal’s concourses. Jahn’s design transforms the functional elements of steel, glass, and lighting into visually expressive, ornamental forms.

Guy Gillette/Photo Researchers, Inc.

American architect Philip Johnson strongly influenced the rise of the postmodern style of architecture. His design for the AT&T Building (now the Sony Building), constructed in New York City in 1984, had a particularly strong impact. The building’s architectural devices, such as the use of allusion in its Renaissance detail and Chippendale-style pediment, make it a symbol of postmodern architecture.

References

“Milich, Klaus. “Theories of Postmodernism.” Trustees Dartmouth College 2004. Web.

“Reed, T. V. “Theory and Method In American Cultural Studies.” 1997. Web.

“Hoffman, Louis, Ph.D. “Premodernism, Modernism, & Postmodernism: An Overview.”

“Weiss, Shannon et al. “Postmodernism and Its Critics.” Web.

Lobell, John. “Both-And” A New Architectural Concept”. Arts Magazine. 1968.

“Pluralism. Microsoft ® Encarta ® 2007. © 1993-2006 Microsoft Corporation.”

“Roth, Leland M. “American Architecture.” Microsoft® Encarta® 2007 [DVD]. Redmond, WA: Microsoft Corporation, 2006.”