Abstract

This paper focuses on exploring a monumental effect of a single small object inside the vast space. The concept of monumentalism refers to huge structures made of stone and created in public places. Pyramids, platform mounds, and cenotaphs are the core representatives of the monumental architecture. As a rule, such object serves for religious or immortalisation purposes, thus embodying greatness and rationality.

This essay studies the effect of Boulléee’s cenotaphs in the framework of modern urban mass, primarily exterior, but also interior. The essay starts with the presentation of the background of monumentalism and its role in architecture. The body of the paper discovers Boullée’s approach to the design of cenotaphs, the monuments in a place that does not contain the remains of the deceased one that serves as a symbolic grave.

For instance, one of the most prominent works of Boullée is cenotaph for Newton towering as a symbol of Enlightenment ideals. As noted by Kaufmann, the purpose of such a great piece of art is to inspire and envision through special forms in order to create a totalising architecture: “the curvature alone, without beginning, without end, is to dominate”. Boullée was utilising geometrical forms not only as a heritage of Ancient times, but more as a way to re-consider the role of the monumental architecture.

Another work of the mentioned architect, the Opera House designed as cylindrical construction with a domical crypt, is a vivid example of his interest in geometrical forms. Furthermore, the essay discusses other works of Boullée that represent the authors’ integration of classical elements and drama closely intertwined and balanced. The conclusion section completes the essay and enumerates the key insights.

Introduction

Space is the paramount tool of monumentalism and avant-garde art that have always been different in scale and dimension. The former significantly exceeded the reality, and the latter seemed to raise and flow in parallel. At a time when classicism reigns in Europe, and urban architectural ensembles obey strict canons and clear rules, Etienne-Louis Boullée, the French visionary draftsman, acts as one of the first architects to challenge nature.

With his incredible projects, he changes the very essence and purpose of architecture. The pivotal objective of this paper is to reveal Boullée’s perception of monumentalism and the effects his architecture makes, focusing on the role of a single object in the vast space. The struggle for new forms along with the inability to fit the reorganization and reorientation of the 19th century predetermined Boullée’s architectural works.

Background

In theoretical projects of public constructions, Boullée aspires to evoke the exalted feelings in the audience through architectural forms that reflect immensity capable of inspiring fear, the greatness of the world, and divine wisdom relating to the very beginning of time. Simultaneously, there is a strong influence of antiquity, especially those of Egyptian architectural structures. A distinctive feature of the works by Boullée is the abstraction of geometric forms of antique works and their transformation into a new concept of monumental construction, which possesses the tranquillity and ideal beauty of classical architecture along with a considerable expressive power.

Inspired by the work of the architect Nicolas Le Camus de Mézières’ The Genius of Architecture; or, The Analogy of That Art with Our Sensations (1780), he began to develop his theory of such architecture, in which infinite perspectives and geometrically pure monumental forms devoid of adornments are to evoke feelings of recovery and anxiety. More than any other architect of the Enlightenment, Boullée was obsessed with the idea of the ability to induce a sense of the presence of a single object in the space as the divine.

Monumentalising Effect of Boullée’s Cenotaphs

Cenotaphs were known in ancient Egypt, Greece, Rome, and in the Middle Ages in Europe as monuments for people buried in a foreign land. Boullée’s off-scale projects are addressed to eternity and memory. A concrete correlation of classics along with fantastic and unrestrained monumentality in the projects of church buildings amazes the viewers. Projects of the Metropolitan Church, the Cathedral, as well as the churches of Saint-Philippe-du-Roule resemble the fantasies of Piranesi on the theme of Roman classics.

One may note grandiose caisson vaults, giant colonnades, and insignificantly small figures of people. If it were not for the illusion of sight, cross-domed, and with porticoes and colonnades, the facades would seem quite realistic. However, the pictures of the church in Dayte in the form of a giant cone above the hemisphere or the Tower of Babel astonish viewers as something unearthly.

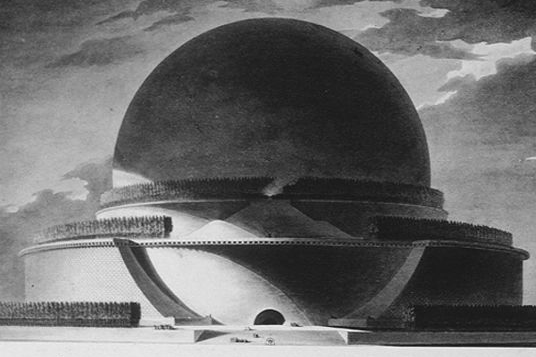

The cenotaph for Newton Memorial was to be a huge hollow ball 150 meters high, which, on the one hand, was supposed to resemble the shape of the Earth, and on the other hand, the very apple that, according to a legend, fell on the scientist’s head (see Figure 1). Today, the specified project is preserved in the National Library in Paris. This sphere was to be cut into a round foot, on which it was supposed to plant cypresses. In this project, the architect turned to the form of the Earth – sphere – as a symbol of entirety.

At the same time, it also recalls the apple that fell on Newton (according to the legend, the scientist discovered the law of universal gravitation in his garden under the apple tree). In the giant cenotaph of Newton, a strong fire, personifying the sun, was to burn at night. In the daytime, the rays of the daylight, seeping through special holes that imitate the constellations, were to create the illusion of a starry sky, sanctifying and inspiring with its rays.

It is cypress trees that were to be planted on a three-level cylindrical base that in ancient Greece and Rome had become a symbol of sorrow and mourning. The spherical portal was to replace a long dark tunnel leading into an immense void to the sarcophagus of Newton. Here, the artificial starry sky was to generate the effect of infinity – a special state of the psyche struck by the grandeur of the universe.

As a consequence, one should to emphasise the divine mind capable of perceiving this greatness. Even though Boullée strives to implement innovation, classicism in his works predominates. His projects of triumphal arches, although fantastic, but, nevertheless, are traced in the classical Roman canons, often in combination with the monumental forms of architecture of the Ancient East.

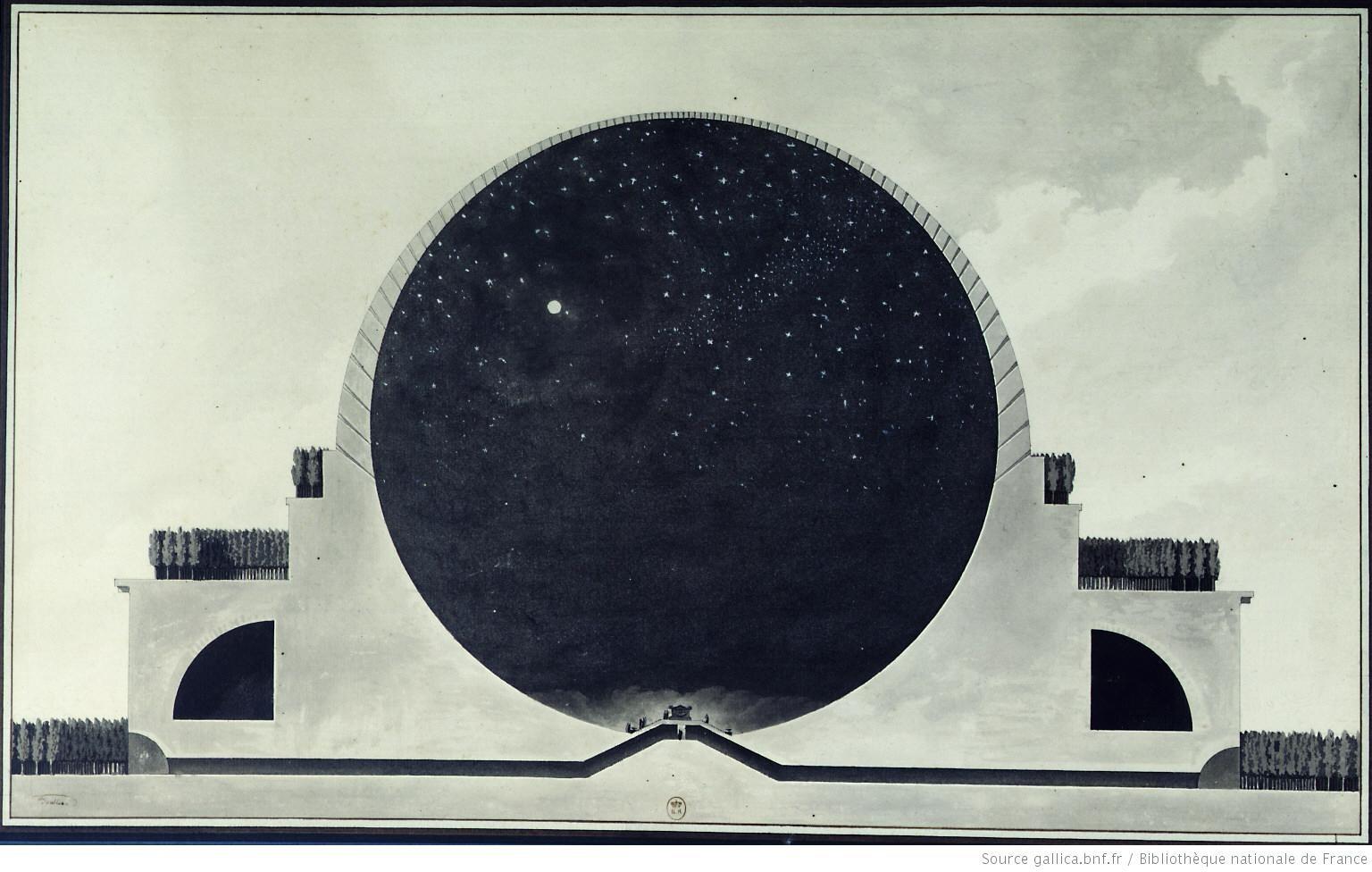

Interior

The interior of Newton Memorial is empty, and only a sarcophagus is present. Designed as a building with curvature structures yet without the beginning and the end, it seems to dominate over people and the world in general (see Figure 2). The interior of Metropolis is also great, especially its dimensions with nocturnal rites. In its turn, the Opera House consists of three structures – the focal rotunda and two side buildings, while it is almost empty inside.

The mentioned examples are characterised by the motif of tension in the space. The interior objects are so small compared to the exterior that they generate anxiety and monumentalism. The very power of the space becomes evident while observing Boullée’s cenotaphs and other architectural works inside. At this point, “the room becomes a vast magnetic field traversed by innumerable lines of force.” Creating the void through the compositional devices of emptiness and simplicity, the architect achieves the effect of monumentality.

Neurological Effect

The geometrical experiments of Boullée are known for their megalomaniacal schemes causing a neurological effect. The architectural ideology of the mentioned architect declares its propellant attitude towards a city and nature, while lurking behind re-considered yet remaining self-destruction. The neurotic attitudes were caused by the inability of architecture of that time to explain and address the crisis of design that led to the concentration on the internal design with an attempt of aligning technology and substance. The connection between rapidly-developing technology and art resulted in utopia and the emergence of a suprastructural guise.

Speaking more precisely, one may note that the core of the neurological effects lies in dissonance between the forms accepted previously and new industrial design. The abrupt contrast between small and large objects utilised by Boullée is the classical balance power that creates irreconcilable buildings.

The neurological aspect is largely associated with not only architectural situation but also a political context. Taking into account that France was a country with progressive capitalism, its architects and Boullée as well were feared of inconsistency with advanced ideology and their outdated forms. Tafuri defines such a situation “neurotic formal and ideological contortions” resulting from altered law and failure of architects to understand the historical premise of this change.

In this regard, Boullée rebels against the system and attempts to relaunch architectural traditions in order to make them closer to the existing political organization. Instead of comprehending that visual communication entered the subsequent stage of development, the architect’s neurosis was contributing to imbalance and retardations. The order and disorder became closer to each other, and there was no need to oppose them since ideology and poetry of the object integrated significantly. Thus, the neurological aspect of Boullée’s architectural views is associated with the inability to adopt new tendencies and protest against them resulting in utopia.

Urban Mass

The mentioned architect also attached great importance to the element of mystery in his works, especially to those that are associated with urban mass. Such a “poetic” approach to architecture is also observed in its symbolism as a predecessor of romanticism of the 19th century. This idea was expressed in a transparent haze enveloping the interiors of his Metropolis. Here, the light is filled with the grandiose brick ball in the design is rather ambitious.

Despite the fact that according to political views, Boullée was a convinced Republican, he had the idea of creating monuments dedicated to the worship of a powerful, higher being that goes in line with the nine points of monumentality proposed by Sert, Léger, and Giedion. The project of Metropolis with its aspiration to distinguish every object of the building may be referred to the first point of monumentality, namely, to the symbol of the architect’s ideas on the continuum of the past and the future. More to the point, one may align Boullée’s works with the third point of monumentality suggested by Sert, Léger, and Giedion regarding the role of every bygone period of history.

In particular, the specified architect endlessly repeats single elements placing them in a vast space and emphasizing their smallness. Referring to the political situation occurred during the Revolution, it is possible to note that Boullée anticipates the third point of monumentality that was written much later. The architect accepts the classical forms of antiquity and his teachers, yet he also develops them to the logical end. For the above reason, he places his geometrical forms in an open space, thus symbolizing their autonomy and juxtaposing them with the absence of classical forms.

The Municipal Palace rests on four watchtowers, thereby demonstrating the connection between society and the law. The focal dome is the most significant place since superimposition along with rotoreflection symmetry that expands the space, both external and internal. The mentioned dome turns out to be a catalyst in the building’s proportions and monumentality. Considering the historical context, it is possible to assume that disunity of France at that time was the source of the given idea. In particular, the aim of The Municipal Palace is the commemoration of monarchy via the purification geometry.

It seems that the mentioned building contradicts with the fourth point on monumentality that declares decadence of monumentalism within the last years and its almost complete failure to link society and architecture. Indeed, even though the given architectural style might be incomprehensible for some people, the works of Boullée werestill representing the social concerns and tendencies. At the same time, the seventh point directly corresponds to Boullée’s works in an attempt to monumentalise social life and transfer it to future generations. For example, the Municipal Palace vividly demonstrates the architect’s intention to perpetuate the social life of those times.

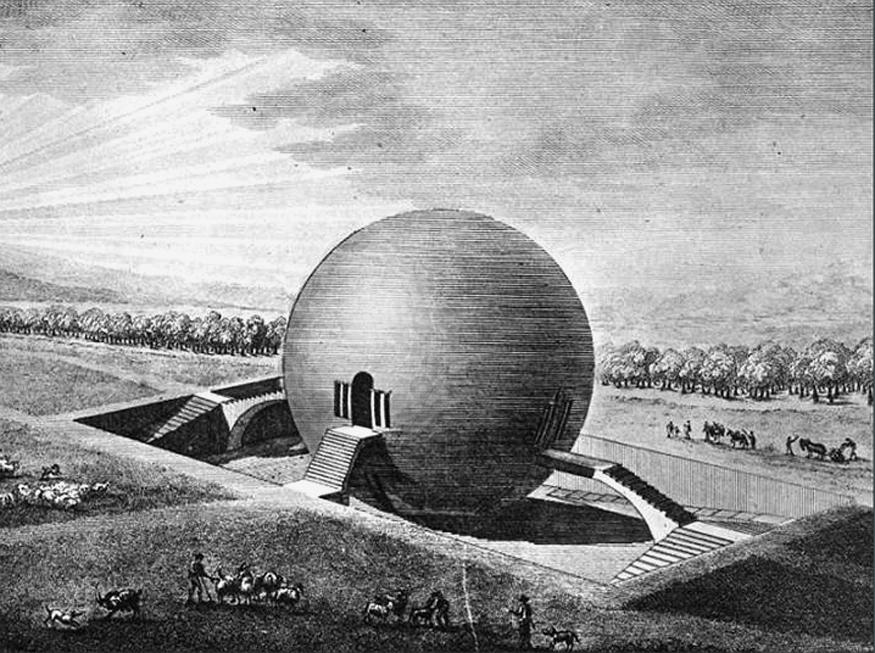

Other elements of the compositions of this architect are triumphal columns, the arches, and colonnades. A monumental effect of a single small object inside the vast space can also be detected in the works of the architects of Boullée’s period. Ledoux can be noted for his pure geometry and Shelter for the Rural Guards building as a vivid example of monumentalism (see Figure 3). Starting from the canons of the classical style, he, nevertheless, processes them, rejecting the excesses of decoration, splendour, and complicated structures. Working with the use of antique colonnades, porticos, and warrants, Ledoux introduces his innovative and ascetic vision of forms.

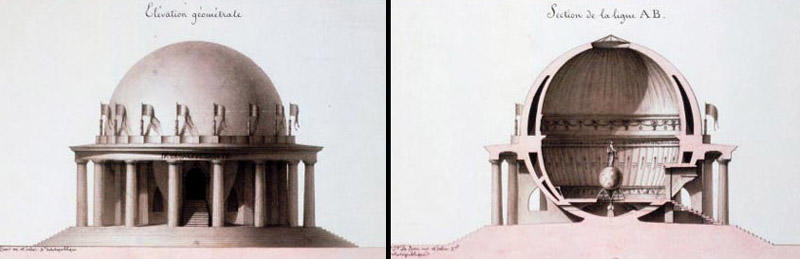

One may observe a clear, constructively simple shapes and clean volumes with powerful stonework and a contrast of geometric proportions. Another prominent architect whose works may be discussed to reveal the essence of a monumental effect is Lequeu. Most of his works integrate classicism and avant-garde as a part of the visionary architecture, yet it is still possible to point out his Temple de l’egalite in this paper (see Figure 4). In this regard, Ledoux and Boullée are quite similar. Strict, justified, useful, and rational in forms – it is these issues that contribute to the creation of a monumental effect.

Critics

Boullée was often criticised for his commitment to the grandiose plans. However, his works should not be regarded as the projects created for the real implementation since they are rather “fantasy” designs. In his desire to create a unique architecture for an ideal, new social order, Boullée refuses decorative details, minimising the number of small elements – the structures are not strikingly elegant and pompous, but monumental and daring solemnity.

It goes without saying that the pivotal reason for the fact that these innovative ideas were never implemented is the incredible size of the buildings. Due to his admiration for the monumental projects, Boullée was often accused of megalomania. Nevertheless, his fantasy had no boundaries, and, therefore, Boullée did not limit himself to anything, even the laws of physics. Ledoux and Lequeu were criticised by their coevals for eccentricity and provocative style as well.

Integrating the Works to Reveal Key Aspects

With the aforementioned discussion in mind, it seems essential to distinguish and summarise the key aspects that are characteristic to monumentalism of a single small object in the vast space. Among the most successful methods of creating a monumental impact, it is possible to note contrasting (displacement of opposing elements of the project) and the use of light and shadow to highly innovative and represent the architecture of that time. The considered projects, especially those of Boullée, amase with the confidence and skill, with which they transform traditional forms, establishing new compositional links between the latter.

In particular, the combination of equivalent elements without the mandatory separation of the center along with a powerful contrast of geometric forms, large, smooth wall surfaces (almost devoid of windows), top light, and horizontal completion of buildings of the architects evoke the feeling of greatness and splendor as well as awe to some extent. A rather discreet décor – most often rhythmic repetition of any motive – is another critical architectural component.

In the discussed buildings, and especially in the projects, a number of devices have been identified such as the isolation of every architectural volume when the ties characteristic of the composition of classicism are broken, while new ones are in the process of becoming. It is especially critical to emphasise that the mentioned visionary architects, primarily Boullée, design their works focusing on space and environment.

As stated by Najder-Stefaniak, to achieve the monumental effect, the architecture juxtaposes human environment and the space she or she lives in. With this in mind, it is safe to assume that valuation and rationality in designing the projects lead the architects to the creation of their oeuvre. In Boullée’s works, urban mass and interior are both filled with single objects located in space that is rather wide. Boullée considered the elementary geometry as the basis for his grandiose architectural projects. By discovering new forms, the architect employs lighting (light and shade) in order to emphasise monumental dimensions and reveal the character of a certain building via transitions in space.

Conclusion

To conclude, it should be emphasised that a monumental effect of a single object in the vast space is created by such visionary architects as Boullée, Ledoux, and Lequeu. It was revealed that the especial role is played by Boullée’s cenotaphs, including Newton Memorial, and other works. Solemnity, autonomy, and extraordinary dimensions – all this characterized the architect’s monumentalizing effect.

More to the point, the neurological aspect of his creation is conditioned by the crisis in architecture and the inability to handle it, which also was a consequence of the changing political regimen. In general, the most distinctive feature of Boullée’s works is the presence of a small object in an open space, be it interior or exterior. The above method creates a sense of stoppage in the continuum, enclosing the space and making it structured and separated.

Bibliography

Aureli, Pier Vittorio. The Possibility of an Absolute Architecture. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2011.

Cairns, Graham. Visioning Technologies: The Architectures of Sight. New York: Routledge, 2017.

Ching, Francis DK. Architecture: Form, Space, and Order. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2014.

Coates, Nigel. Narrative Architecture. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2012.

Costelloe, Timothy M. The sublime: From Antiquity to the Present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Elahi, K. Taufiq. “Of Boullée and Kahn, and the Spirit of the Sublime.” Journal of Science and Technology 21, no. 1 (2014): 61-69.

Emmons, Paul, Jane Lomholt, and John Shannon Hendrix. The Cultural Role of Architecture: Contemporary and Historical Perspectives. London: Routledge, 2012.

Faidit, Jean-Michel, and Marvin Bolt. “The Magic of the Atwood Sphere.” Planetarian–Journal of the International Planetarium Society 42, no. 2 (2013): 12-16.

Farrelly, Lorraine. The Fundamentals of Architecture. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017.

Ferng, Jennifer. “Monstrosity and Excess in Jean-Jacques Lequeu’s Visionary Architecture.” Fabrications 26, no. 1 (2016): 4-26.

Joye, Yannick, and Jan Verpooten. “An Exploration of the Functions of Religious Monumental Architecture From a Darwinian Perspective.” Review of General Psychology 17, no.1 (2013): 53-68.

Kaufmann, Emil. Three Revolutionary Architects. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society, 1952.

Kierkuc-Bielinski, Jerzy J. “Back to the Olympic Future: Stadia’s Political Role.” World of Antiques & Art 83, no. 1 (2012): 32-35.

Kim, Mi Sang. “Poem in the Order and Tradition: Bibliothek 21.” International Journal of Sustainable Building Technology and Urban Development 4, no. 2 (2013): 111-115.

Molle, Guillaume. “Monuments and people in the Pacific.” Journal of the Polynesian Society 124, no. 3 (2015): 317-319.

Najder-Stefaniak, Krystyna. “Architecture as the Art of Shaping the Human Environment and Human Space.” Dialogue and Universalism 17, no. 12 (2007): 115-121.

Qiaohui, Tong, and Dong Weimin. “Visionary Architect Going Well Beyond His Time: Etienne-Louis Boullee.” Huazhong Architecture 9, no. 1 (2013): 2-7.

Rosenblum, Robert. Transformations in Late Eighteenth Century Art. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1967.

Samuels, Ivor, et al. Urban Forms. London: Routledge, 2012.

Schneemann, Peter J. “Monumentalism as a Rhetoric of Impact.” Anglia 131, no.2 (2013): 282-296.

Sert, José Luis, Fernand Léger, and Siegfried Giedion. “Nine Points on Monumentality.” Architecture Culture, n.d., (1943): 48-51.

Tafuri, Manfredo. Architecture and Utopia: Design and Capitalist Development. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1976.

Terzoglou, Nikolaos-Ion. “Ideas of Space from Isaac Newton to Étienne-Louis Boullée.” South African Journal of Art History 27, no. 1 (2012): 29-44.

Vidler, Anthony. “Researching Revolutionary Architecture”. Journal of Architectural Education 44, no. 4 (1991): 206-210.

Wright, Lawrence. Perspective in Perspective. New York: Routledge, 2017.

Appendix A