Price ceiling

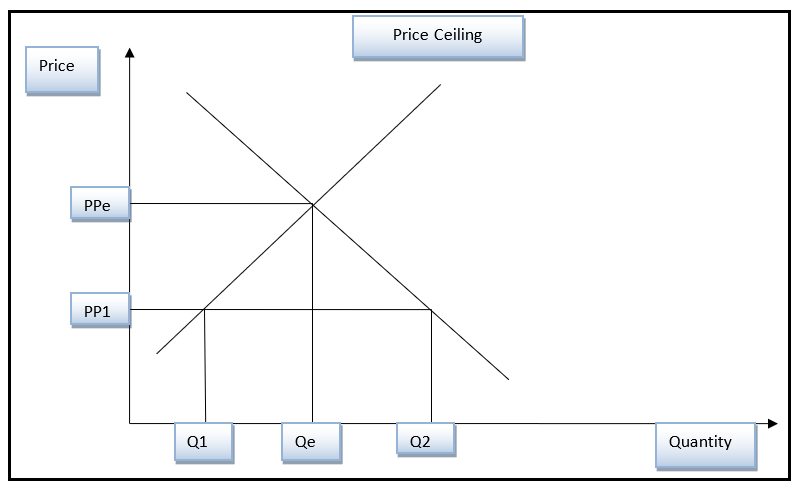

Under price pricing, the government puts a maximum price level that should not be exceeded. It is often set below the market equilibrium. This price control technique affects the stability in the market because it creates a situation of excess demand. An example of a price ceiling is rent control. In some cities, the local governments often impose a price ceiling on housing to make housing reasonably priced for low-income households (James, 2012). Graphically, the price ceiling is illustrated below.

In the graph above, the equilibrium price and quantity are PPe and Qe respectively. If the price ceiling is set at PP (below the equilibrium price PPe), then there will be a shortage in quantity supplied. The shortage is equivalent to the difference between Q2 and Q1. It can be observed that at PP1, the market is not in equilibrium.

One key advantage of this price control technique is that it deters suppliers from charging outrageously high prices for scarce commodities and services. This prevents the exploitation of consumers. Secondly, the price ceiling helps the government to make the cost of living inexpensive, especially when an economy is going through a phase of high inflation. When a country is experiencing upward inflationary pressure, the prices of commodities tend to rise faster than income. Thus, the price ceiling will help maintain the purchasing power of the currency.

On the other hand, the pricing ceiling has a number of shortcomings. The first drawback is that it discourages the suppliers from producing. This is due to the fact that the forces of demand and supply are not allowed to function freely. The temporary shortage that is caused by the price ceiling will make the suppliers cut production and the quantity that is offered for sale because they lack the financial incentive to produce more. This will in turn cause prices to fall. Also, the price ceiling may encourage the growth of black market due to shortages and other vices such as hoarding in the economy.

Law of Demand – Art Museum

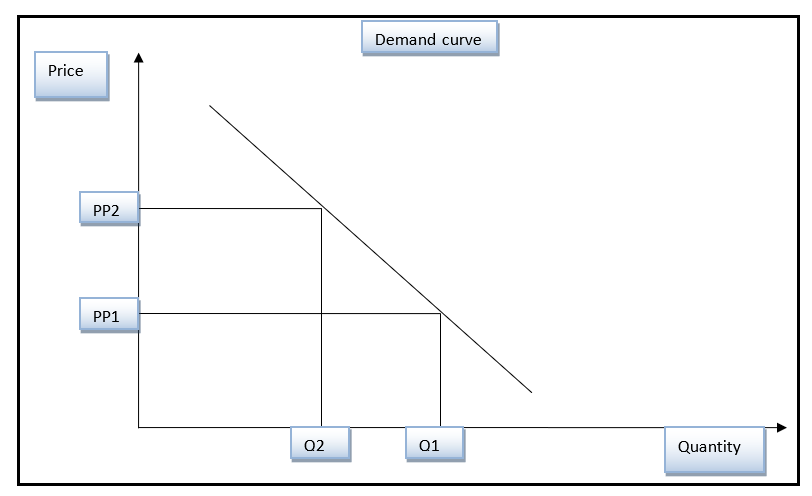

The law of demand outlines that there is an inverse relationship between price and quantity, ceteris paribus. This implies that when the price of a commodity increases, then the quantity demanded decreases while holding other factors that affect demand constantly. This explains why the demand curve slopes downwards as illustrated below. The law applies to normal goods because there are goods that behave differently to price changes. For instance, the demand for luxuries will go up when the price increases. Also, the law omits other factors that affect demand.

Based on the demand curve above, if the price increase from PP1 to PP2, the quantity demanded will decrease from Q1 to Q2. The increase in price can either cause an increase or a decrease in revenue. The change in total revenue after a price increase will entirely depend on the elasticity of the commodity. In this scenario, the increase in price at the art museum causes a decline in total revenue. This implies that the commodity is price elastic. In other words, the quantity demanded is quite sensitive to changes in price. Thus, if the price increases by one unit, then the quantity demanded will fall by more than one unit. This explains the decrease in total revenue.

Elasticity of coffee

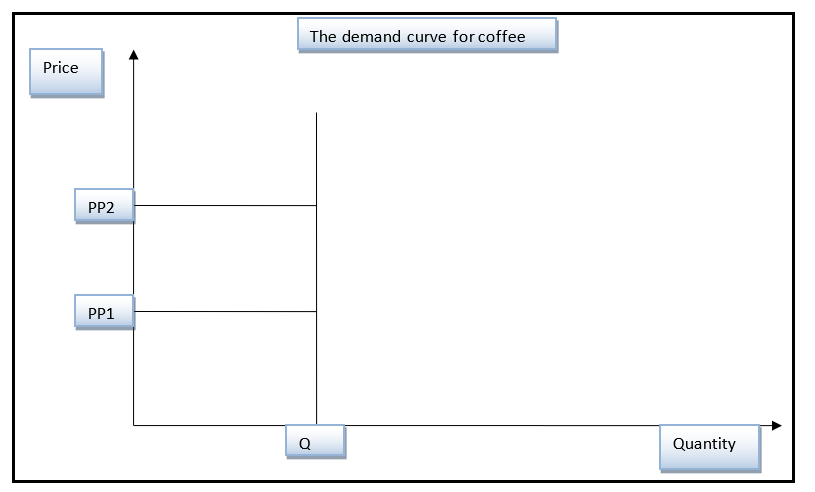

In this scenario, the price does not affect the quantity of coffee consumed. It indicates that the commodity is perfectly inelastic. It portrays a scenario where the quantity consumed remains the same irrespective of changes in price as illustrated in the diagram below.

In the diagram, if the price increases from PP1 to PP2, then there will be no change in quantity. This shows that demand is not responsive to changes in price. Therefore, the demand for coffee is price inelastic.

Determinants of elasticity of demand

The first determinant of elasticity is the nature of the product or service. For instance, if a commodity is a necessity, then the demand is likely to be price inelastic because it will be consumed irrespective of the price. On the other, the demand for luxuries is likely to be price elastic because a small change in price is likely to cause a large change in quantity demanded. The second determinant is the ease of substitutability of a commodity. For instance, the demand for a commodity or service that has several close substitutes is likely to be sensitive to changes in price. However, if a product or service has few substitutes, then it is likely to have an inelastic demand. Brand loyalty can also affect the elasticity of a commodity. It supersedes the sensitivity to price changes. This makes the demand for some brands to be price inelastic. An example is a demand for German-made cars such as BMW in the German market. The consumers in Germany will be less sensitive to changes in the price of such as cars as compared to consumers in other parts of the world because of brand loyalty.

Another factor is the proportion of income that is spent on a product or a service. For instance, commodities on which consumers spend a small proportion of income have inelastic demand because their consumption will not be affected by changes in price. On the other hand, commodities that take a large portion of the income will be sensitive to price changes. The final factor is the duration of a price change. For instance, non-durable goods are likely to be inelastic in the short-run and elastic in the long-run. This is due to the fact that in the short-run, the consumer may not make changes in consumption, but in the long-run changes can be made to the consumption behavior. For instance, if there is a sudden rise in the price of gas, then the consumer may continue to use the same quantity as before. However, after a long period and the price increase persists, the consumer may resort to other options such as carpooling and buying hybrid cars. However, this may not apply to durable commodities. Durable goods such as machinery are less elastic to price changes.

Demand for Orange juice and brand of orange juice

The demand for orange juice is more elastic than the demand for a specific brand of orange juice. This can be explained by the concept of brand loyalty. Once a certain group of consumers is loyal to a specific product, then the quantity they consume will not be sensitive to changes in price.

Reference

James, S. (2012). How the rich get richer, rental edition. New York Times. Web.